Against the Current, No. 10, September/October 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Editorial: Korea Workers Take the Lead

— The Editors -

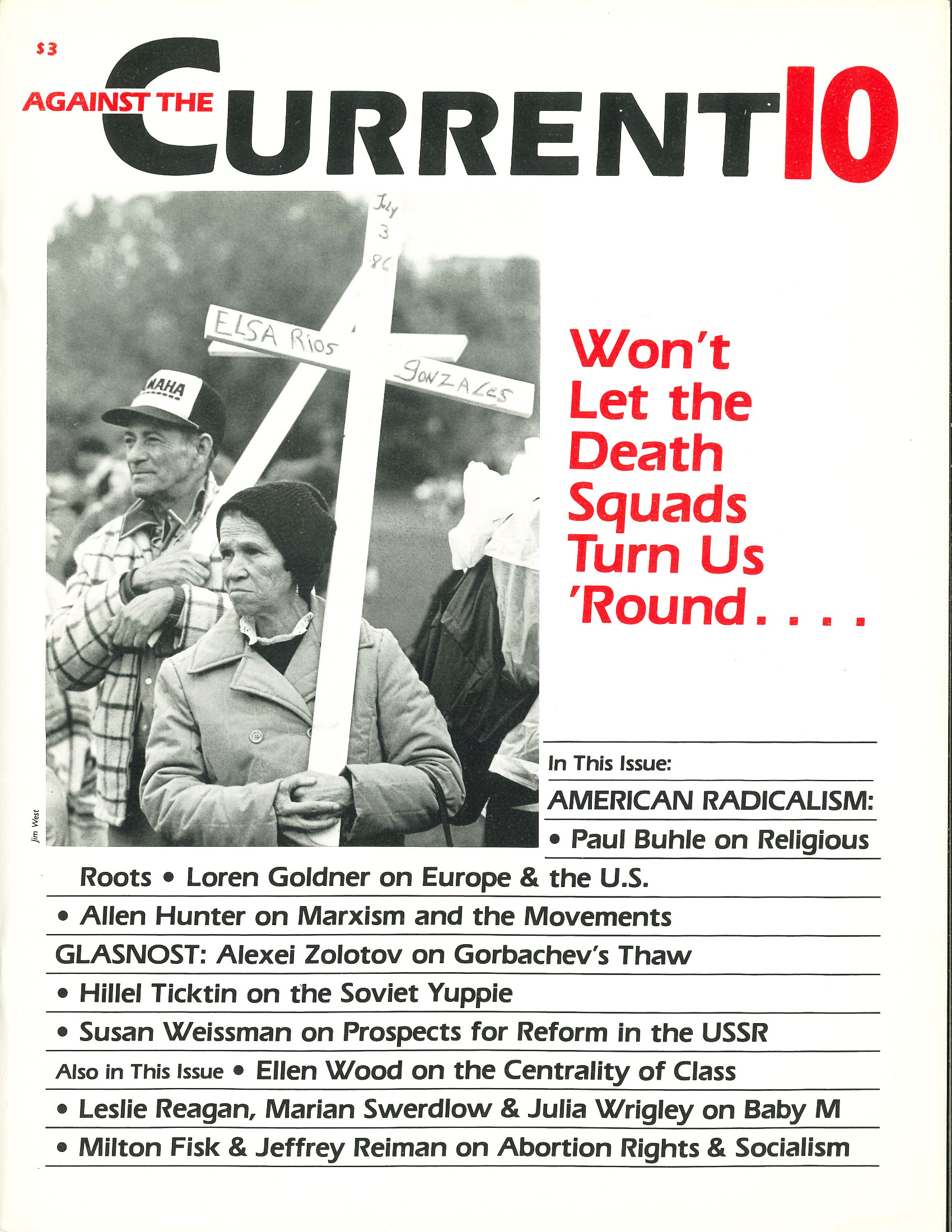

Death Squad Activity in Los Angeles

— Susan Wyler -

A Strategy for Irish Solidarity

— Bob Nowlan -

Why Class Struggle Is Central

— Ellen Meiksins Wood -

Random Shots: More Mines for Ronnie

— R.F. Kampfer - American Radicalism

-

Reflections on American Radicalism, Past & Future

— Paul Buhle -

Afro-Anabaptist-Indian Fusion

— Loren Goldner -

A Response to Paul Buhle: Limits of Religious Rebellion

— Allen Hunter - Abortion Rights & Socialism

-

A Group Liberationist Approach

— Milton Fisk -

Why Socialists Should Support Individual Natural Rights

— Jeffrey Reiman -

A Rejoinder: The Fallacies of Liberal Rights

— Milton Fisk - Looking at Glasnost

-

Gorbachev's Glasnost: Thaw II

— Aleksei K. Zolotov -

The Soviet Yuppie Takes Power

— Hillel Ticktin -

Who Benefits from Reforms?

— Susan Weissman -

Response to Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Justin Schwartz -

Reply to Question on Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Michael Löwy -

Whose Baby Is It Anyway?

— Julia Wrigley -

Surrogacy Is a Bad Bargain

— Leslie J. Reagan - Review

-

Wuthering Heights Revisited

— Michael Sprinker

Julia Wrigley

JOHANNA BRENNER AND Bill Resnick’s article (ATC #9) on the Baby M case offers welcome thoughts on a tough problem. I don’t agree with their conclusion, however, and would like to propose a different way of looking at surrogacy.

While expressing sympathy for Whitehead, Brenner and Resnick support the judge’s decision to award custody to the Sterns (the biological father and his wife). They do so on two grounds. They first reject any notion of “biological essentialism” that would grant Whitehead, as the child’s natural mother, a priority claim to the baby. They then argue that as Whitehead has two other children, it is more just to give this new child to the Sterns, who have no others, and who expected this child would be theirs.

Brenner and Resnick too quickly dismiss “biological essentialism.” There are strong reasons to support the rights of biological parents to their children. No other social policy provides such protection against class bias.

By biological essentialism, I mean the rights of both biological parents to their children. Brenner and Resnick apply the term only to the mother. They then argue it violates feminist principles to support biological essentialism.

If we adopt a broader view of biological essentialism, we can support this principle. We can then oppose inhumane decisions such as the trial judge’s in the Baby M case, which denies the mother access to her child. Brenner and Resnick’s proposed policies would systematically disadvantage mothers — nearly all working-class — who enter surrogacy agreements, while in practice privileging the middle-class fathers.

The class bias in the Baby M case was so overt and ludicrous that the expert witnesses earned general derision. But the class questions go far beyond this level.

Surrogacy agreements inevitably involve structured class inequalities between the father and the mother. In garden-variety custody disputes, the parents initially had some kind of relationship. Class differences in such cases seldom are as wide as those between the partners in surrogacy agreements.

In the United States, class differences often translate into different childrearing styles.

Given the elite backgrounds of most judges and their identification with the privileged, the chances of their deciding surrogacy disputes in favor of the natural mother are small. Their very definition of good childrearing is likely to differ from that of the mother.

A Policy for Equality

Since the deck will be stacked against the surrogate mother in custody proceedings decided on the basis of the “best interests” of the child, we should think of social policies that will not automatically disadvantage biological mothers. I suggest we emphasize the overriding rights of biological parents except in cases where they abuse their children.

Consider historical and ongoing instances where parents have lost their children. Such child loss has occurred in three main ways. In the first, the powerful wanted to exploit children. Slave parents had no rights to their children. In their case, biological parenthood counted for nothing.

More recent cases of child loss have occurred on a different basis. In some such cases, the powerful took other people’s children because they wanted to raise them as their own. This occurred to Sephardic Jews in Israel in the 1950s, as described by Adam Keller.

“Overcome by culture shock, the Yemenites fell prey to a group of unscrupulous doctors and nurses who put hundreds of Yemenite babies up for adoption by childless Ashkenazi couples, telling the natural parents the babies had died. The conspiracy was extensive enough to include the systematic issuance of fake death certificates for the adopted children and to ensure that, over several decades, demands for an investigation were hushed up. The affair remained an open wound for the parents who lost their children and for the Yemenite community as a whole.” (“Sephardim and Ashkenazim Ethnic and Social Conflict,” New Politics, Summer 1987, 178).

In Argentina, the secret police under the junta seized babies from their imprisoned mothers. They gave the babies to childless supporters to raise as their own. The moving film, “The Official Story,” depicts the anguish of an adoptive mother who learns that her much-loved child came to her through the torture and death of the child’s mother.

Child loss also occurs even today through authorities taking the children of despised subgroups, with the claim that this is in the children’s “best interests.” Gay and lesbian parents still face this threat. Short of people’s being imprisoned or put to death, could there be a greater loss or a dearer sign of a group’s vulnerability?

Most poor, exploited or stigmatized parents do not lose their children. But given the cruelty of child loss and how it so strikingly affects the most oppressed, we should value biological essentialism. In a society so riven by class inequalities, here is one great simple equality.

We know only too well about the class injustices in children’s treatment. The poor lack medical care for their children, they witness their denigration in the schools, they see them used as cannon fodder by the army, and appalling numbers watch their children stuffed into America’s filled-to-bursting jails.

But still, even in the face of this terrible record of harshness and injustice, the poor struggle to build families marked by love and concern. They receive little credit for what they put into their families, because their mode of childrearing differs from the approved middle-class style. In perhaps the ultimate Orwellian tum, the problems their children can face are attributed to parenting failures rather than to extreme economic inequalities, unmitigated by social programs for children.

Any survey of the childcare literature reveals middle-class condescension toward the childrearing practices of poor and working-class parents. Whitehead was hardly exceptional in facing this cold and critical scrutiny. Given the pervasiveness of this condemnation, biological essentialism provides protection for parents facing custody challenges.

Whatever class differences exist in how to look after children, most parents can safely hold on to them and raise them as they choose. We should not lose sight of how important a right these parents are exercising and should be instinctively wary of any policies that would undermine their claim to their children.

Built-in Bias

Ostensibly neutral judicial proceedings inevitably pose such a threat. There is so little public provision for children that resource differences between parents can and do affect children’s access to good medical care and to quality education. In countless other ways, the middle-class claimants can present themselves as offering the child more than can the workingclass parent, and almost always, they will have more experienced, slicker lawyers to make their case.

The less privileged family might provide the child with love and emotional support lacking in the middle-class household, but this would probably not emerge in a trial. In such circumstances, it is profoundly risky to fall back on judicial determination of the “best interests” of the child in deciding who makes a “better” parent in surrogacy disputes.

Brenner and Resnick’s specific arguments for why the Stems should have custody would, if applied more broadly, make it almost impossible for surrogate mothers to ever obtain custody. They acknowledge the loss of Baby M was a real hurt to Whitehead, but quickly add, “She has two kids and could have another, whereas the Sterns were childless. Rough justice.”

Rough indeed. In almost every surrogate arrangement, the other mother will already have other children (and will have thereby demonstrated her fertility), while the father will have none.

Further, parents who lose a child feel terrible pain even if they have others. Many parents who have lost children through death, or who have lost fetuses through miscarriage, report their anguish when well-meaning friends point out they have other children or can try later for another baby.

Brenner and Resnick’s other argument for awarding custody to the Stems is equally problematic. They argue “Parenthood is not essentially biological. It is social; it comes about when people develop expectations and assume responsibilities.”

Not only does this attack on the rights of biological parents allow the intrusion of strong class bias, but it attaches overwhelming weight to an inherently subjective factor, people’s hopes and expectations.

The actual expression of the Sterns’ expectations occurred in the contract. They had signed what they believed to be a legally binding document with Whitehead. The judge agreed the contract was valid. To reject the contract, as Brenner and Resnick do, but uphold the validity of the expectations based on it, is to reach the same result by a different means.

The contract required Whitehead to anticipate her emotions on the birth of her child. This she did not do, but parents — either mothers or fathers — should not be required to make this prejudgment.

The Sterns’ contract with Whitehead contained a provision that reveals quite a bit about the nature of their expectations. They made it clear they expected a healthy child. The contract specified that Whitehead was to have amniocentesis and William Stern would decide, on the basis of the results, if she should have an abortion. This was too much even for the trial judge, as it clearly abridged Whitehead’s constitutional rights.

The contract also specified that if Whitehead miscarried, or if the baby were born dead, she would receive only $1,000 and not $10,000. After all, she would not have delivered the goods.

While William Stern’s desire for a biological child may compel our sympathy, as it compelled Brenner and Resnick’s, the actual steps he took toward his goal were distasteful in their explicit exploitation of another human being, his child’s mother. The contract made clear the power relations between the two.

We need a surrogate policy that provides more social justice and less class bias than the one suggested by Brenner and Resnick. The goals of such a policy should be to minimize class privilege in custody decisions; to safeguard handicapped children from abandonment by one or both parents; to reduce painful, protracted litigation by providing clear rules; and to minimize the use of surrogacy.

I suggest that surrogate contracts should be made unenforceable. No parent should face the loss of a child on the basis of a decision made before the child’s birth.

If the surrogate mother changes her mind and decides she wants the child, she should not be able to push the father out of the picture. He also is entitled to a relationship with the child. Where the biological parents cannot agree on custody, they should share the child’s custody.

This does not mean the child must spend equal amounts of time in each home. As in custody cases arising between parents with prior relationships, it does mean that both biological parents would be entitled to access to the child and neither could be stripped of his or her parental rights (except in cases of abuse).

In disputed cases, the best alternative is to guarantee each parent visitation rights, but to decide physical custody on a “best interests of the child” basis. This would allow class prejudice to enter the case, but the effects of such bias would no longer be so radical as they are today, as neither parent could be entirely excluded. Custody arrangements could be renegotiated as the child got older and parents’ visitation rights would be guaranteed.

This policy would minimize surrogacy. The biological father and his mate would have to consider the possibility that, if the mother changed her mind, they would have to share custody. They would face the prospect of being connected with a woman they barely knew, a woman moreover who is almost certainly of a different social class and who has a different lifestyle. The Stems made it clear that such an option would be unacceptable to them.

As a further disincentive to surrogacy and a support for the child, the biological mother of course would have the right to decide on an abortion. But if a handicapped child is born, the father should have to provide support.

This policy would not be ideal, but it avoids the gross injustice of the judge’s ruling in the Baby M case. People might argue it would be bad for children to be shared between the parents. This is not clear, however; in the last decade or so traditional notions of what’s “bad” for children in this regard have changed greatly.

Rather than seeing the child as the possession of one parent, coveted by the other, a more collective model of custody is now gaining ground. It admittedly would be tricky to apply this to parents in surrogate relationships, but it would by no means be impossible. It might produce children with a depth of social understanding denied to those who grow up in one narrow social milieu.

On a broader level, we should work for more social services for children so class distinctions between parents become less critical. Children’s life chances should not depend on their parents’ bankbooks. Given our exploitative and materialistic society, we should see the merits of “biological essentialism” in safeguarding the rights of poor, working-class or sociallystigmatized parents.

September-October 1987, ATC 10