Against the Current, No. 10, September/October 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Editorial: Korea Workers Take the Lead

— The Editors -

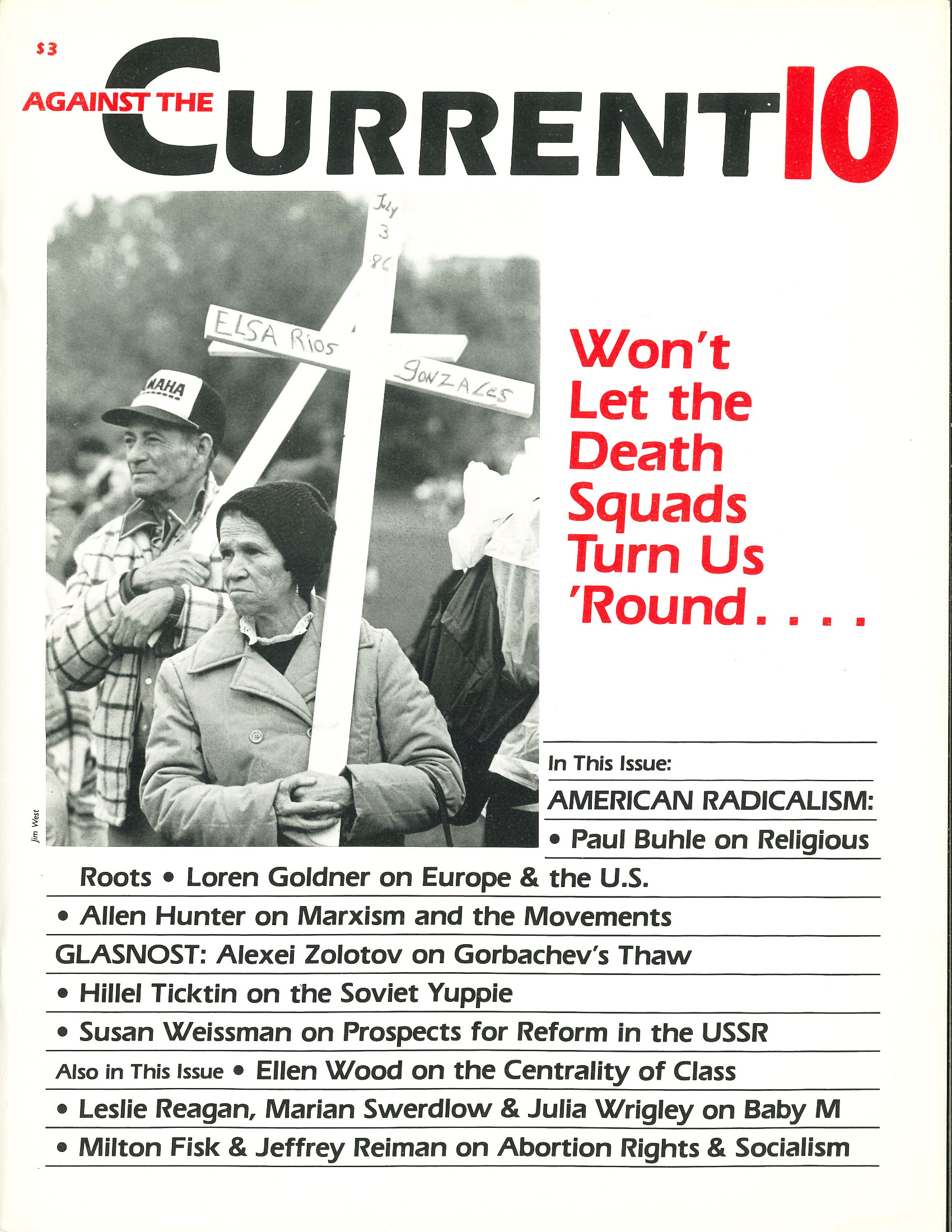

Death Squad Activity in Los Angeles

— Susan Wyler -

A Strategy for Irish Solidarity

— Bob Nowlan -

Why Class Struggle Is Central

— Ellen Meiksins Wood -

Random Shots: More Mines for Ronnie

— R.F. Kampfer - American Radicalism

-

Reflections on American Radicalism, Past & Future

— Paul Buhle -

Afro-Anabaptist-Indian Fusion

— Loren Goldner -

A Response to Paul Buhle: Limits of Religious Rebellion

— Allen Hunter - Abortion Rights & Socialism

-

A Group Liberationist Approach

— Milton Fisk -

Why Socialists Should Support Individual Natural Rights

— Jeffrey Reiman -

A Rejoinder: The Fallacies of Liberal Rights

— Milton Fisk - Looking at Glasnost

-

Gorbachev's Glasnost: Thaw II

— Aleksei K. Zolotov -

The Soviet Yuppie Takes Power

— Hillel Ticktin -

Who Benefits from Reforms?

— Susan Weissman -

Response to Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Justin Schwartz -

Reply to Question on Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Michael Löwy -

Whose Baby Is It Anyway?

— Julia Wrigley -

Surrogacy Is a Bad Bargain

— Leslie J. Reagan - Review

-

Wuthering Heights Revisited

— Michael Sprinker

Hillel Ticktin

AFTER WATCHING Soviet TV fairly steadily over last week, I have learnt what is meant by glasnost. It is the right to express different ways of implementing official policy.

No one expresses a contrary view, no one whosoever.

When the question of the nature of the opposition to glasnost is posed, on Soviet TV, on British TV, in the Soviet press and to visiting Soviet writers, there is only one standard reply. The opposition is the middle-level bureaucrats and the overall psychology of inertia existing throughout the regime.

Since this reply has been standard since the thirties it is difficult to put much faith in it. After watching Soviet TV and consistently reading the Soviet press some answers are beginning to emerge.

Last week there was a debate on the introduction of individual private enterprise. That was on Thursday.

One writer expressed disagreement with the overall tone since he felt that the real issue was the problems of existing nationalized enterprise, which led to such absurdities as the theft of a generator from one customer’s car to assist another client to get back on the road.

Given the enormous difficulties in obtaining spare parts, this was evidently a normal occurrence. Hence many speakers raised the whole question of the manner and ease of supply of such parts and other supplies to the private sector.

The writer implied that the discussion of the difficulties of the reform was far too negative, since it was bound to be better — even with problems of supply. On the other side, it became clear that the officials concerned with inspection were worried that the matter would get out of hand. Some felt that they would be afraid to use private services.

A clip was shown of a private medical specialist who was harassed by tax and other inspectors to the point of his customers being cross-questioned on their treatment.

A speaker pointed out that unless there was competition, little would be changed. A case was built for proceeding further in the direction of private enterprise by reducing the tax burden, providing premises and inputs from the state sector, and changing attitudes.

Since this is the official view, the debate was not a real debate. The critique from the inspectors was only a grumble and a warning but not opposition. A view stating that such a move was dangerous since it would lead to greater inequality in income and provide facilities only for the well-off could not be aired.

Yet, that is clearly what is going to happen. The fact is that ordinary people cannot benefit from better repair facilities for cars or consumer durables since they have no cars and few consumer durables. By and large the reform will be good for the Soviet yuppie.

Blaming Lazy Workers

That indeed was the picture that emerged from watching Soviet TV. The news service has moved from depicting the usual boring steel plant over fulfilling the plan to showing the same steel plant under fulfilling the plan in a style which can only be called comic.

The announcer informs the listeners that the news “only just in” shows that the following plants have not fulfilled the plan. A clip follows in which a commission goes to inspect the errant plant. They are well-dressed, well-fed, often trim gentlemen who patronize the workers called up to the screen.

When these gentlemen were asked what they were doing about housing, the reply came that the workers must work and then everything would work out.

That indeed was the constant refrain. Prime Minister Ryzhkov, when in Sverdlovsk, addressed an audience in which his message was the necessity of order, discipline and hard work. The contrast with the previous octogenarian incumbent could not have been more glaring.

Well dressed, fit and determined, Ryzhkov is the yuppie’s man. If the workers work, then the Soviet intelligentsia will be happy.

The opposition as seen on TV boils down to the Soviet worker, who is too lazy at the moment to perform properly. There are also various officials who are not prepared to prod the workers or take steps to ensure proper performance, and they too are at fault.

Indeed, this view is confirmed by a reading of the Soviet press and journals. Gorbachev saw last November the issue of discipline as the first priority of the regime. Speech after speech railed against anarchy and promoted order, work and control.

Democracy cannot be taken too far. One-man management, elected (indirectly) from below, is the basis of the regime. What workers can think of having to select, through a- system of delegates, among five candidates approved initially from above, does not have to be spelled out.

The insistence on one-man management makes it absolutely clear that the Soviet regime will not even move to the mitbesimmung (“co-determination”) of West Germany. Few workers will be bought off with talk of a democracy which is essentially cosmetic.

It is not difficult to see that the opposition to Gorbachev will come from those concerned with workers and those who fear that the workers may act against the regime once their conditions do actually worsen as a result of the regime’s proposals.

The new leader is not stupid, however, unlike previous Soviet general secretaries. The political maneuver is indeed quite shrewd. There is a definite attempt to form alliances with some social groups and concede to others.

The ultimate effect will be to separate out the workers from the intelligentsia and divide them between skilled and less skilled.

An attempt is being made to appeal to women by forming women’s councils and possibly by alleviating their lot. In relation to the question of women, one Soviet program involved a TV discussion by two men and two women on the family. The message was the need to save the family.

The debate was dominated by a male chauvinist who would have been unbelievable to a Western audience. He declared that the whole problem was the debasing of the role of the man. The man, he stated, was superior. Women ought to have the right to go back to the home. He was standing up for those women who wished to stay at home.

He accused the other man, a writer, of not standing up for men because he did not agree with him. The writer felt constrained to play down his disagreement and announce that he too stood up for men.

The real problems of women and the family did get a limited airing from the other participants, and it was not clear whether the male chauvinist was there to be exposed to all as such or because that was a common view in the regime.

What was clear was that an attempt was being made to address the real problems of low pay, enormous workloads after work in the home, and the heavy manual nature of much of women’s work in production. Whether anything will emerge is dubious, but the regime might well be given credit by many women for asking the right questions, even if they do not provide the right answers.

Too Much Equality?

The slogans today are in a form familiar to Thatcherite Britain: against levelling, too great a degree of equality in pay. Wage rates are being changed to permit widening of differentials.

Skilled workers or those called skilled workers, which is far from the same thing, will clearly benefit. Heads of brigades, foremen are due to play a crucial role in the reform. They will be on the norming committee, which sets the speed of the production line, the wage rate for the job, etc.

The new decree on work norms, of December 1986, is clearly seen as crucial in reducing featherbedding, increasing the intensity of work and ensuring greater steadiness in work rhythms. It is not likely, however, that the skilled workers together with those workers in immediate charge of other workers will counterbalance the dissatisfaction of the vast majority at having to work harder for the same pay.

Gorbachev is clearly hoping that the appeal to democracy, the attempt to provide better social amenities, the talk of better housing and the like will at least neutralize this real opposition on the shop floor.

At the moment the problem is not that the workers will revolt but that they will ignore commands to improve productivity and if pushed might even act collectively to do so. Even if they respond for a short time, they are all too likely to revert to normal practice after the supervision slacks off.

Soviet workers would have to be quite drunk to accept these changes, especially when faced with fellow workers earning much more than they do.

The implied temptation to conform and also get promoted can only succeed with a few. Far more likely to work is the attempt being discussed to introduce unemployment. Its introduction would be a radical break with the past fifty or so years and the political consequences could be equally radical

The discussion of women being returned to the home was an echo of the view, long held by some, that such would be a method of reducing the level of unemployment once featherbedding was properly reduced.

The real opposition is political and is reflected in the highest circles. To move to such market-type reforms might destabilize the system, and some leaders do not want to take the risk.

In the meantime, while the issue is fought out, the position of Soviet yuppies is improving. They have greater freedom of speech, if only within defined limits; they have had salary raises and services are due to get better. Promotion prospects are also looking up.

The head of the Soviet delegation to Spain asked that the reforms be taken seriously. By reciting the varying receptions reform has met with in the West he revealed the seriousness with which the leadership views its reception in the West. That is itself important, showing how much the reforms depend on a deal with the U.S.A.

That does not mean that the reforms are only for show. They are not-but they are not systemic yet either. They are altering the politics of the USSR, placing greater stress on the intelligentsia, skilled workers, etc., rather than trying to encourage each to fight the other, as was the custom hitherto.

On the left of the elite stands Boris Yeltsin conducting a campaign against privilege, if the attack made on elite schools is any indication. Pravda and indeed the Soviet trade-union head made a similar attack at the Twenty-seventh Party Congress, but an attack on this kind of privilege may be little more than bringing the elite itself into the market. It is not abolishing the elite, but only that section of the elite which today is useless.

I have not seen Moskovskaya Pravda, only the report in the London Sunday Times of March 15, 1987, but it fits the style of the new Moscow Party Secretary. Rumor has it that he made his officials dispense with their official vehicles and use public transport just to see how bad it was.

He did not remove their vehicles for more than a day. He is an efficient manager compelling management to manage responsibly. He is asserting the right of management to manage and the responsibility of management to manage responsibly and not in a featherbedded and corrupt manner.

At the same time the KGB, the army and the party apparatus remain the arbiters of power, while the ordinary worker can only watch, wait and hope that his time will also come.

September-October 1987, ATC 10