Against the Current, No. 10, September/October 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Editorial: Korea Workers Take the Lead

— The Editors -

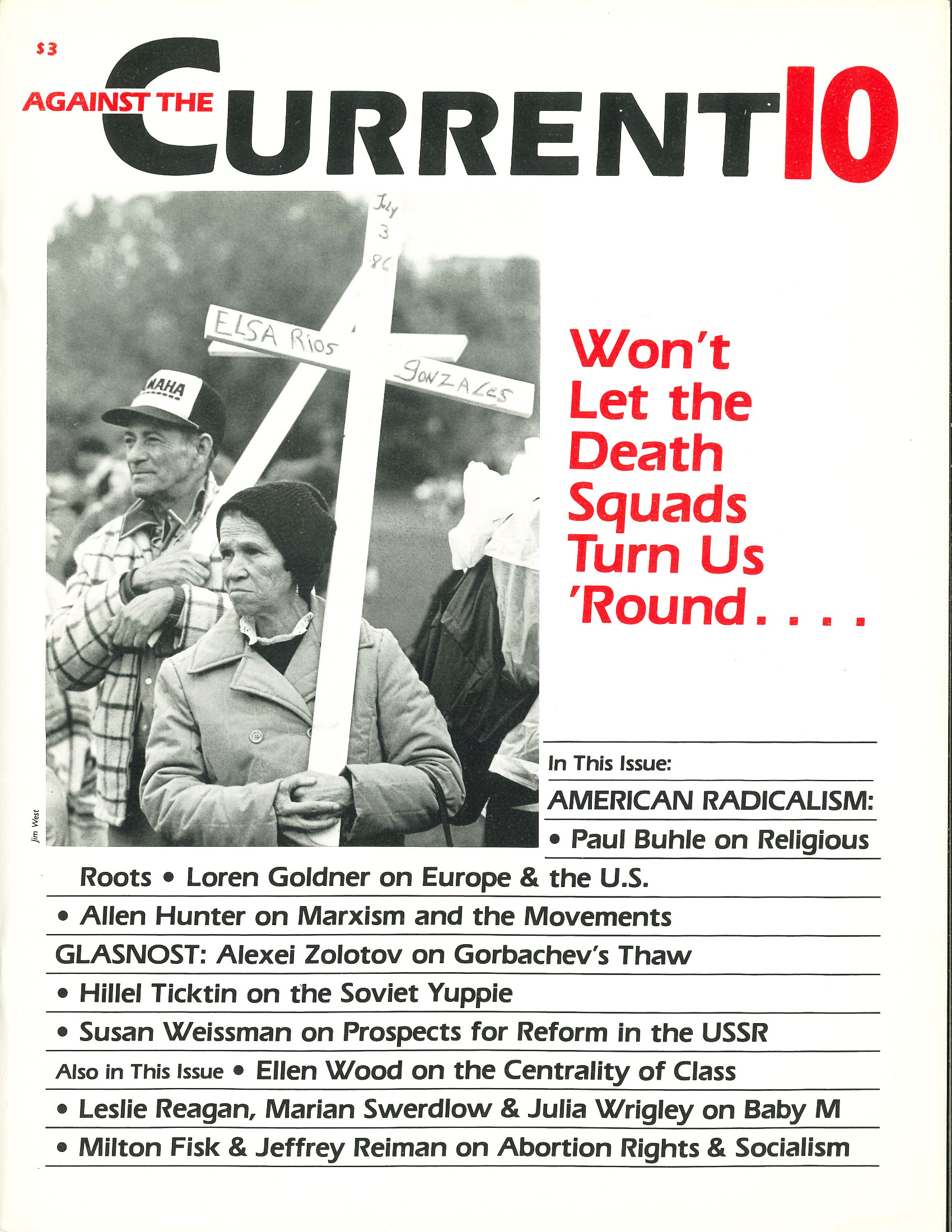

Death Squad Activity in Los Angeles

— Susan Wyler -

A Strategy for Irish Solidarity

— Bob Nowlan -

Why Class Struggle Is Central

— Ellen Meiksins Wood -

Random Shots: More Mines for Ronnie

— R.F. Kampfer - American Radicalism

-

Reflections on American Radicalism, Past & Future

— Paul Buhle -

Afro-Anabaptist-Indian Fusion

— Loren Goldner -

A Response to Paul Buhle: Limits of Religious Rebellion

— Allen Hunter - Abortion Rights & Socialism

-

A Group Liberationist Approach

— Milton Fisk -

Why Socialists Should Support Individual Natural Rights

— Jeffrey Reiman -

A Rejoinder: The Fallacies of Liberal Rights

— Milton Fisk - Looking at Glasnost

-

Gorbachev's Glasnost: Thaw II

— Aleksei K. Zolotov -

The Soviet Yuppie Takes Power

— Hillel Ticktin -

Who Benefits from Reforms?

— Susan Weissman -

Response to Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Justin Schwartz -

Reply to Question on Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Michael Löwy -

Whose Baby Is It Anyway?

— Julia Wrigley -

Surrogacy Is a Bad Bargain

— Leslie J. Reagan - Review

-

Wuthering Heights Revisited

— Michael Sprinker

Aleksei K. Zolotov

SOVIET SOCIETY is at last emerging from the post-Khrushchev deep-freeze. The current thaw is proceeding more rapidly than did its predecessor of the 1950’s and has indeed already erased some high watermarks of that era.

Cultural developments have been the most dramatic.(1) Boris Pasternak is to be rehabilitated as a great writer of the Soviet tradition, and his “Doctor Zhivago” is to be published after thirty years of banning.(2) The emigre novelist Vladimir Nabokov is to be published for the first time.

Even more surprising, the avant-garde poet Nikolai Gumilev, who was executed as an anti-Soviet conspirator in 1921, has been cleared for printing for the first time since 1923.(3) Those works of the late pre eminent Soviet poet Anna Akhmatova, Gumilev’s widow, that deal with him and with their son (a victim of the great purge) have also cleared censorship.(4)

In addition to taking such actions transcending the Khrushchev level of toleration, the regime is recapitulating the 1950s thaw by allowing the display of a series of anti-Stalin novels, plays and films.

Many of these works are of the 1960s that were suppressed until now, including the novel “Children of the Arbat” by Anatoly Rybakov(5) and the play “The Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk” by Mikhail Shatrov.(6) The legalization of the play involves tantalizing prospects, since, to judge by Western reports, it presents both Bukharin and Trotsky with some semblance of historical accuracy and as human, if mistaken, rather than as demonic figures.

The eminent poet and veteran of the earlier liberalization, 53-year-old Andrei Voznesensky, a sponsor of the Pasternak rehabilitation, speaks for much of the Russian intelligentsia in lauding the editors, film directors and theater managers who have initiated the new artistic era.

“These people are leading a cultural revolution — let me correct myself — a revolution by culture,” Voznesensky said in a recent New York interview, and added “It is a revolution of consciousness.”(7)

In addition to the cultural thaw, there is an explicitly political one, but before turning to it, it is important to recall that the cultural developments are implicitly political events of the first rank. “If you read history of Russia, you will find that all the political/social movements which changed our history began in poetry”; Yevtushenko’s slightly ungrammatical English marshals precisely the Russian past to evoke a proper awe for the Soviet present.(8)

Indeed, for two centuries Russian literature has played an immensely greater role in public life than Western literature has in its sphere. Alexander Pushkin, a poet of the stature of Shakespeare, was a primary figure in the early Russian revolutionary movement. French Enlightenment and German Idealism fought their Russian battles in novels and in literary criticism. Feodor Dostoevsky, a novelist, is taken by some as the greatest of Russian philosophers.

In Western literature one must reach back to such figures as Milton, Rousseau, Voltaire, or Goethe to find writers so central to the social process as have been Mayakovsky, Yesinin, and Gorky in our own century.

The cultural upheaval, then, must be understood in Western categories as analogous to a major extension of the rights to free speech, free press and freedom of inquiry.

On more familiar, explicitly political turf, events are almost as striking. Gorbachev’s public attack on his Politburo foe Dinmukhamed Kunayev for “establishing a personality cult” during Kunayev’s twenty-two years of ruling the Kazakhstan party organization is a clear invoking of the substance and vocabulary of the de-Stalinization campaign of the 1950s.(9)

The treatment of Khrushchev himself, an important index of the regime’s readiness to deal with its past, has changed. After his death in disgrace in 1970, Khrushchev was buried in a cemetery for secondary figures, rather than at the Kremlin-an unprecedented slight of a Soviet leader. Credible reports now suggest his remains are to be reinterred in the Kremlin wall.(10)

Additional evidence of the political earthquake is provided by the freeing of many of the jailed dissidents, the allowing of open contact between dissidents and foreign reporters, hints of disengagement in Afghanistan, and the renascence of anti-Stalin historiography.(11) Of special interest to the democratic left is Gorbachev’s February statement that “there must be no forgotten names, no blank spaces, either in history or in literature.”(12)

Eastern European Implications

In East Europe, the new influences from Moscow are recasting the balance between the authorities and their opponents to the latter’s advantage. The Husak regime in Czechoslovakia, which presided over the liquidation of the Dubcek reform of 1968, has come under strong pressure to conform to the Russian liberalization.

As the Washington Post noted, this “is a shift the leadership cannot easily make without undermining its own legitimacy and the record of its eighteen years in power. But in a country where political authority — even by the standards of Eastern Europe — is exceptionally dependent on Moscow, any rejection of the reform course would make Husk’s position equally vulnerable.”(13)

In Hungary, a mainly young crowd of 1,500 marched unhindered in a pilgrimage to several sites associated with the 1956 uprising. This rare, and in recent history unparalleled, event featured speeches calling for democracy, a free press and the rehabilitation of Imre Nagy, prime minister of the rebellious Hungarian regime of 1956. Especially poignant was the public participation in a related observance of Judit Maleter, widow of Pal Maleter, the defense minister of 1956, who was executed in Moscow with Nagy.(14)

The Hungarian protesters are only the first of many in the Eastern Bloc who will doubtless rise to make again the case for causes deemed by the Brezhnev regime to be over and done with.

Already, the Washington Post reports that “there are signs that Czechoslovaks, who have made a virtue of passivity since 1968, have renewed their interest in politics and staked fresh hopes on Gorbachev. Opposition sources maintain that even a small, spontaneous pro-Gorbachev demonstration erupted recently in the industrial town of Pilzen.”(15)

Poland, as might be expected, offers the most complex situation. While providing little in the way of openness (glasnost) and contradictory signals on economic restructuring (perestroika), the Jaruzelski regime has rhetorically embraced the Soviet initiatives with enthusiasm. This embrace was reciprocated by Gorbachev, who “responded quickly by signaling that he considered General Jaruzelski to be the first among equals of the Communist leaders of Eastern Europe.”(16)

The reality is that while Jaruzelski might be contemplating a reform that “would put Poland on a par with China and Hungary, which have gone the farthest in revising the traditional state-run economy,”(17) he has in fact continued in force until now the unimaginative bureaucratic austerity program that has oppressed Polish life for a decade.18

The regime’s actions are indeed so uninspired in their hatefulness that even the official union undertook a campaign against a new wave of price increases. “The government-proposed scope and scale of price increases is unacceptable to working people and therefore we want it revised,” the union stated in words of unwonted bluntness.(19)

Solidarnosc faces obvious difficulties in defining its relationship to the thaw. On the one hand, Soviet Stalinism throttled the movement in 1981, and possibilities for Poland in the context of a Soviet liberalization are positive and awesome. Indeed, the lesson of 1956, 1968 and 1980-81 is plausibly that only the victory of an anti-Stalinist current in the USSR can remove the Stalinist regimes in East Europe.

But then, there is also the painful reality expressed by a Polish dissident: “It would be very difficult for any Pole to say anything good about any Soviet Communist and still maintain his credibility and popularity.”(20)

Even so, Lech Walesa is reported as supporting “the economic initiatives” of Gorbachev, “but not those being introduced in Poland.”(21) There are also indications that Solidarnosc intellectuals Jacek Kuron and Adam Michnik are “inching toward some qualified positive assessment of the possibilities offered by the Soviet developments.”(22)

Lower down in the Solidarnosc ambiance, there are other portents of a linkup between the Polish workers’ movement and the Russian thaw. An unnamed senior editor of Warsaw’s Tygodnik Mazowsze (the country’s most successful Solidarnosc-that is, illegal-paper with 200,000 readers) observed, “It’s amazing in that we’ve been writing far more about developments in the Soviet Union than the official media,” and added, “People are reading Tygodnik Mazowsze to learn about Gorbachev’s refonns.”(23)

And a Warsaw May Day dispatch to the New York Times began, “Polish police officers fell upon workers leaving a Warsaw church today, snatching from them a banner with a quotation from the Soviet leader, Mikhail S. Gorbachev: ‘We need democracy like we need air.'”(24)

Diagnosis and Prospects

With the specters of 1956, 1968 and 1980-81 circling darkly on the horizon, the Russian regime manifestly runs enormous risks in losing the forces of reform in the Eastern Bloc.

Even so, that Gorbachev and his faction have placed themselves and their caste in such peril attests to their intelligence and audacity, rather than stupidity and pusillanimity.

They have taken on the risks because the alternative is even more menacing: the economic decline of the USSR and attendant social, political and military disasters.

These are not vague eventual possibilities, but concrete immediate dangers. For all the Western prattle about Russia’s missing the microprocessor revolution or about a Gorbachev plot to lull the gullible West into accepting devious treaties, what is really occurring is that the Soviet regime is responding, twenty years late, to the warning given by the Czechoslovak economic crisis of the 1960s.

The events of that period, which probably constitute the dress rehearsal for the present Soviet juncture, merit the following review.

In the years 1962-64, the Czechoslovak economy, arguably the most advanced of the Soviet world, stopped growing and then began to contract. The Prague regime, prefiguring the Russians of the early 1980s, first sought to overcome the crisis through tentative, meliorative steps that were thwarted by bureaucratic inertia.

In 1966-67, the bolder diagnosis began to circulate that the Stalinist system of centralized detailed planning had reached its limits. The argument gained credence that a complex modern industrial economy cannot be run from a single center, that rational calculations cannot be undertaken for the many-sectoral economy that is the legacy of earlier Stalinist successes.

For this reason, the argument went on, the regime would have to cease substituting its crude extrapolations for more informed, rational calculations carried out at the points of production and consumption. These would be calculations made by managers, workers and consumers.

This was the primary motivation offered for the introduction of the market, a technical cybernetic imperative. It is of course true that this engineering imperative became bound up with other issues of incentives and cross-caste rivalries, for example. Some reforming technocrats saw a chance to move up in the income distribution. But the main force of the market argument lay in the cybernetics of the effective use of information.

In an astounding series of events that unfolded between late 1967 and the Soviet invasion of summer 1968, this main force carried all before it. An at first incredulous world saw the Czechoslovak party depose the antediluvian Stalinist Novotny regime, embrace the radical anti-bureaucratic diagnosis of the economic crisis, raise the technocrats behind the market-decentralization reform to ministerial rank, and initiate its own campaign for glasnost and perestroika, what we know as the Prague Spring

Legacy of Blunted Reforms

Two paramount inferences need to be drawn in surveying the 1962-68 experience and kept in mind in evaluating its Soviet reprise. First, in contradiction to the main Western opinion that the Russian party, qua Communist, cannot carry through a significant market reform, history shows that such a party can undertake precisely such an endeavor.

Second, the upshot of the Russian suppression of the Prague reform is not the episodic Soviet Stalinist victory of 1968, but the much more fundamental displacement of the Czechoslovak contradictions to their eventual maturing two decades later in an economic crisis in the USSR itself.

That maturing is now upon us. Brezhnev’s pyrrhic victory became Andropov’s and Chernenko’s Stalinist liability. Gorbachev has taken on this legacy of stagnation, and now stands where Dubcek stood in late 1967: in the generation’s climactic party showdown with the traditional Stalinist

Should he prevail, and should the Czechoslovak dialectic continue in force, meaningful economic decentralization, freewheeling market socialism, will be at hand.

The Czechoslovak logic, which the Soviets may well be compelled to obey, is somewhat as follows. Industrial decentralization means that, in the quest for productive efficiency at the microeconomic level, enterprise managers are freed from rigid state determination of input and output configurations, including choice of suppliers and product prices. They are free to choose the technology and to some extent free to determine the use of profits, to solicit capital financing, and to fix the structure of investment.

This confers a great deal of political and social power on the newly enfranchised managers, and to limit the undesirable use of this power, the enterprise workers are to be set up as a countervailing force via workers’ councils.

If the dual enfranchisement is to mean anything, both managers and workers are to show “initiative,” instead of the repetition of old formulae. This means that whatever the desires of the regime might otherwise be, it will be driven to expand free speech so that economic, management and technical issues might be discussed and worked out at the molecular level, rather than resolved by the brute force of omnipotent, but incompetent, central planners.

But economic, management and technical matters are not perfectly separated away from social, political and cultural issues. The two realms are connected by countless strands of logic, interest and custom, and any attempt to explore the one realm leads inevitably into an exploration of the other.

This dilemma was faced by Dubcek’s regime twenty years ago and was resolved by the daring acceptance of the exploration of both realms, with the consequent acceptance of a free press, free workers’ movement, free reconsideration of recent history, and of the risks run in the relation with Moscow.

Dubcek’s dilemma of twenty years ago is Gorbachev’s today. It comes down to this, that the regime can opt for economic growth, reform and decentralization, only if it at the same time accepts a concomitant vast extension of democratic rights of discussion and social participation.

This is the secret of the Prague Spring of 1968 and is very likely the secret of a Moscow Thaw of 1987. It is not sentimental liberalism that is overturning Stalinist censorship and raising the shades of Bukharin and Trotsky in the USSR. It is, rather, hard-boiled calculation, based on a growing awareness that the Russian economy has come to the end of the Stalinist road and that the only way out is political, humanistic democratization and decentralization.

The most dramatic instances of cultural and political liberalization so far have been associated with the need to mobilize allies for the showdown with the Stalinists. But should the reformers succeed in this historic battle, there lie ahead conflicts with both bureaucratic sloth and the enfranchised technocrats, each of which conflicts will call for extending the reform.

A Long-Awaited Moment

Czechoslovakia was well into this latter phase when the Russian intervention wrote an end to the experiment in “socialism with a human face.” Left alone, who knows how much farther the Prague Spring might have gone?

The Russian experiment operates without this constraint. The USSR will be left alone, with the Red Army probably swept up in the process, rather than poised as a threat to it.(25)

That is to say, Thaw II may be the beginning of the political revolution in the Eastern Bloc. If so, it is not clear that it will run its course in quick order, although the weight of historical evidence favors apocalyptic change in Russia, when once it is ready to change, just as it favors more predictable, drawn-out convulsions in the West.

The Soviet crisis appears to be the beginning of the working out of the repressed contradictions of half a century, and both the contradictions and repression are of an order experienced by no other society, ever. The Russian integuments have been strained correspondingly, and as they snap, everything becomes possible.

“This may be the moment I’ve been waiting for all my life,” says Voznesensky in an anticipation to be embraced wholeheartedly by the revolutionary left.(26)

Notes

- See the Washington Post, March 25, 1987, p. C1 ff., for a summary of some of the high points of the last year.

back to text - The Soviet magazine Ogonyok plans to publish excerpts; the complete book is to be available in 1988. New York Times, March 22, 1987. See also Christian Science Monitor, May 5, 1987.

back to text - La Repubblica, June 22-23, 1986.

back to text - New York Times, March 25, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 14, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, April 30, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 16, 1987.

back to text - Christian Science Monitor, May 15, 1987.

back to text - Washington Post, March 15, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 15, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 17, 1987; New York Times (Week in Review), May 10, 1987; Washington Post, March 25, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, April 30, 1987.

back to text - Washington Post, March 18, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 16, 1987; Washington Post, March 16, 1987.

back to text - Washington Post, March 18, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 27, 1987.

back to text - Washington Post, April 7, 1987.

back to text - Washington Post, April 7, 1987.

back to text - Washington Post, March 20, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 27, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 30, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 27, 1987.

back to text - Washington Post, April 4, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, May 2, 1987.

back to text - “According to a bitter joke circulating in Prague, a man who remembers the 1968 Soviet invasion wonders whether, in light of Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s liberalization, it is now Czechoslovakia’s turn to send ‘fraternal assistance’ to the Soviet Union.” New York Times, (Week in Review}, April 5, 1987.

back to text - New York Times, March 16, 1987.

back to text

September-October 1987, ATC 10