Against the Current, No. 10, September/October 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Editorial: Korea Workers Take the Lead

— The Editors -

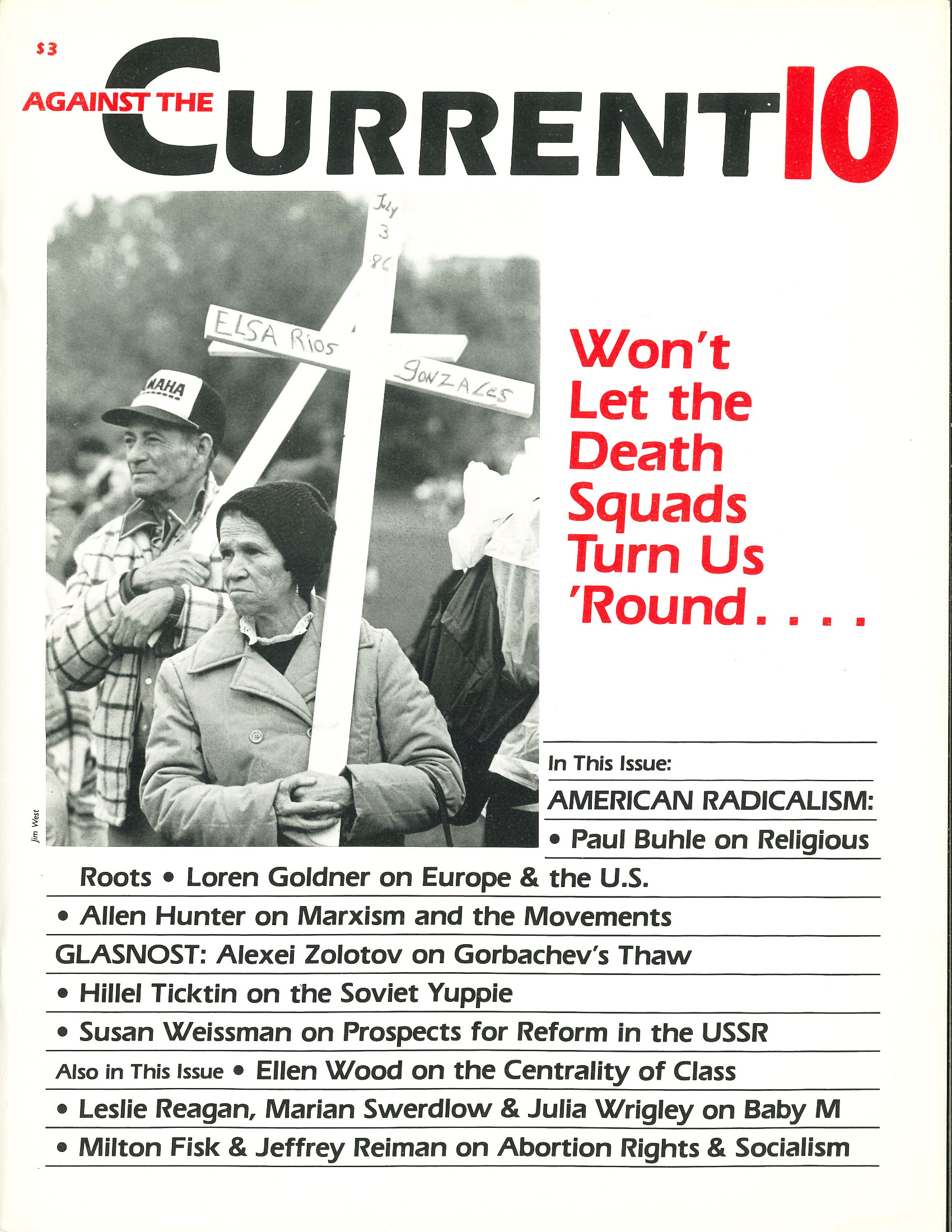

Death Squad Activity in Los Angeles

— Susan Wyler -

A Strategy for Irish Solidarity

— Bob Nowlan -

Why Class Struggle Is Central

— Ellen Meiksins Wood -

Random Shots: More Mines for Ronnie

— R.F. Kampfer - American Radicalism

-

Reflections on American Radicalism, Past & Future

— Paul Buhle -

Afro-Anabaptist-Indian Fusion

— Loren Goldner -

A Response to Paul Buhle: Limits of Religious Rebellion

— Allen Hunter - Abortion Rights & Socialism

-

A Group Liberationist Approach

— Milton Fisk -

Why Socialists Should Support Individual Natural Rights

— Jeffrey Reiman -

A Rejoinder: The Fallacies of Liberal Rights

— Milton Fisk - Looking at Glasnost

-

Gorbachev's Glasnost: Thaw II

— Aleksei K. Zolotov -

The Soviet Yuppie Takes Power

— Hillel Ticktin -

Who Benefits from Reforms?

— Susan Weissman -

Response to Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Justin Schwartz -

Reply to Question on Reform & Bureaucratic Power

— Michael Löwy -

Whose Baby Is It Anyway?

— Julia Wrigley -

Surrogacy Is a Bad Bargain

— Leslie J. Reagan - Review

-

Wuthering Heights Revisited

— Michael Sprinker

Milton Fisk

MORALITY IS NOT something that comes zooming in out of the blue to control our lives, but is a human institution fashioned to fit human purposes. Where our purpose is the transformation of society, only a morality that allows for social transformation is feasible.

The critical role of morality is then limited by the context of ongoing endeavors. A morality that allows for social transformation cannot reject conflict and confrontation, but will have a place for the class, feminist and minority struggles.

An interesting feature of the liberal morality that Jeffrey Reiman espouses is that it is ill-suited to conflict and confrontation. It attributes rights to individuals on the basis of features they would have in isolation from social groups and not on the basis of features they have as members of social groups. Such rights have been called natural rights.

Since individuals on all sides of a social conflict have these natural rights, it becomes impossible to engage in struggles that pit one group against another without violating natural rights. Group struggle is then illegitimate. The consistent liberal moralist wants instead to reconcile conflicts not through struggles but through debate or compromise.

Most socialists, however, see struggle as inevitable. They do not think that the conflicts inherent in class, gender and racial divisions are to be overcome through debate and compromise. For them, there will be confrontations resulting in the loss of accustomed freedoms and deep suffering.

Natural rights have served well for the protection of these accustomed freedoms. They protect the right of the capitalist to invest and profit and the right of the worker to contract for a wage. If, though, we want an end to wage labor, then within the liberal framework we must be able to show that the resulting restriction of the capitalist’s freedom to invest and profit is not a violation of the capitalist’s natural right to choose a form of life.

It might be argued that it is not a violation of this basic right since the form of life in question leads to the exploitation of others. And surely this is bad, at least for the workers who are exploited. So no natural right of the capitalist is violated by ending the wage system since the capitalist has no right to exploit others.

Surprisingly enough the argument works in reverse as well. Do workers have a right to try to end exploitation? Using exactly the same argument we must conclude that they do not since ending exploitation is a bad thing for capitalists. This leaves us with the paradox that workers both have and lack the right to end wage labor. This is the kind of jam one gets into within the perspective of natural rights.

Natural rights are then a barrier to struggles. Women, the working class and minorities will need a morality that assigns them rights, but not rights common to their antagonists. Women have a right to choose in reproductive matters, and workers have a right to end exploitation. These rights are based on their interests as women and as workers; they are not nullified because, as in the liberal view, everyone has a natural right to freedom of decision and from suffering.

The Nature of Human Nature

Reiman and I agree on the importance of human nature as a basis for rights. We differ in the way we view human nature. The dominant theme in ethical thinking has been that of a constant human nature across groups and across time as well. And of course this dominant theme implies the view that rights are also constant across groups and time. It makes debate and compromise, rather than struggle, the vehicles of social change since it allows an appeal to a common humanity to end conflict.

l differ with Reiman since l challenge the idea of a constant human nature, There are important differences between humans in different groups, differences reflecting their formation by these groups.

This does not mean that the capacity to reason, to choose, to be self-aware and to suffer are not vital to all humans. But once we are done listing such common features, there will be others that are not common to all humans yet are equally. vital to the humans endowed with them. Women, for example, are not just rational and self-conscious beings but have a specific nature that reflects both their oppression and their potential to overcome it.

There is no basis for saying that common features are morally more important than the vital group-specific features. After all, if human nature is what we base morality on, then there is no basis for giving moral precedence to the common over the group-specific features of a person’s nature.

What does this tell us about natural rights? It is only the common features of human nature that are selected as the basis for natural rights. In a world of conflicting groups, it will often happen that per sons in one group can flourish as humans only if those in another do not.

To flourish as a human now means realizing both the common and the group-specific sides of one’s humanity. Members of an oppressed group may then be able to flourish only by dealing with their oppressors in ways that deny their oppressors not just the realization of their group-specific nature but also the realization of some of those common features of human nature.

Whether their oppressors’ freedoms may be restricted depends not on limits set by natural rights but on the needs of those in the oppressed group to realize themselves. With no alternative to a constant human nature, Reiman can’t see how group-specific rights are based on human nature.

Is it true as Reiman claims that oppression involves the violation of natural rights? Surely oppression involves preventing people from flourishing as humans, but since there is no constant human type the rights violated by a given form of oppression are the rights appropriate to individuals of a quite specific human type. They have these rights on the basis of what they are, and what they are is never what they would be apart from their social circumstances. Oppression violates not natural rights but rights based on the whole constellation of features that makes a specific human type.

The Roots of Solidarity

How can members of one group be committed to the struggles of another? Reiman would have us believe that progressive men are committed to feminism because the natural rights of women are being violated.

There is something odd about this. First, the oppression of women is too specific to be a matter of violating a constant human nature. Second, there is a better account of solidarity.

Progressive men are committed to feminism because men belong to groups whose interests are advanced through solidarity with women. Working-class men and Black men will not win their struggles against capitalism and racism without the support of women. Some men, to be sure, support feminism out of idealism, but a major contribution to ending women’s oppression will not arise from this idealism. Reiman’s approach to solidarity with the oppressed makes it unclear how solidarity could ever be effective.

It was in regard to abortion that I raised the issue of rights. I claimed that the pro-choice position makes sense if rights are based on human nature shaped by groups. I tried to show that the natural rights perspective did not allow either the pro or anti-choice forces to gain a decisive edge.

Reiman disputes this, claiming that a crucial moral boundary is passed once a human has an interest in continued existence. Since the fetus has no such interest, there would be no right to life for the fetus.

Moral boundaries are notoriously hard to stake out. Reiman’s attempt is no exception. When I am asleep, when I am sacrificing myself for a cause, and when I am suicidal, my interest in my own continuation is not a priority. I am still capable of taking an interest in my own continuation since I can wake up, lose my zeal, or get counselling.

The fetus too can change into a being with an interest in continued existence. It is a mistake, then, to base a moral boundary on a state of consciousness since we change consciousness without losing rights.

The point is not, of course, that fetuses have a natural right to life. It is that argument and counterargument on the matter balance out evenly. To avoid stalemate we need to abandon natural rights for rights based on humans as formed in groups. Then we can say that women have a right to choose in reproductive matters, because if they don’t their struggle is weakened on all sides.

In sum, the liberal view of rights adopted by Reiman is deficient in two respects. First, it is unsuited to a politics of struggle, in contrast to a politics of debate and compromise. Second, it operates with the theme of a constant human nature, in contrast to the theme of a variable human nature more suited to understanding a social world of conflicting groups. Based on these defects, his criticisms miss their target.

September-October 1987, ATC 10