Against the Current, No. 9, May/June 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Baby M, Family Love & the Market in Women

— Johanna Brenner & Bill Resnick -

A Life Worth Living: Benjamin Linder, 1959-87

— Alan Wald -

El Salvador: Popular Movement Gains

— David Finkel -

A Personal Account: Awaiting Deportation

— Margaret Randall -

Comment from Margaret Randall

— Margaret Randall -

Random Shots: Ghosts in the Machine

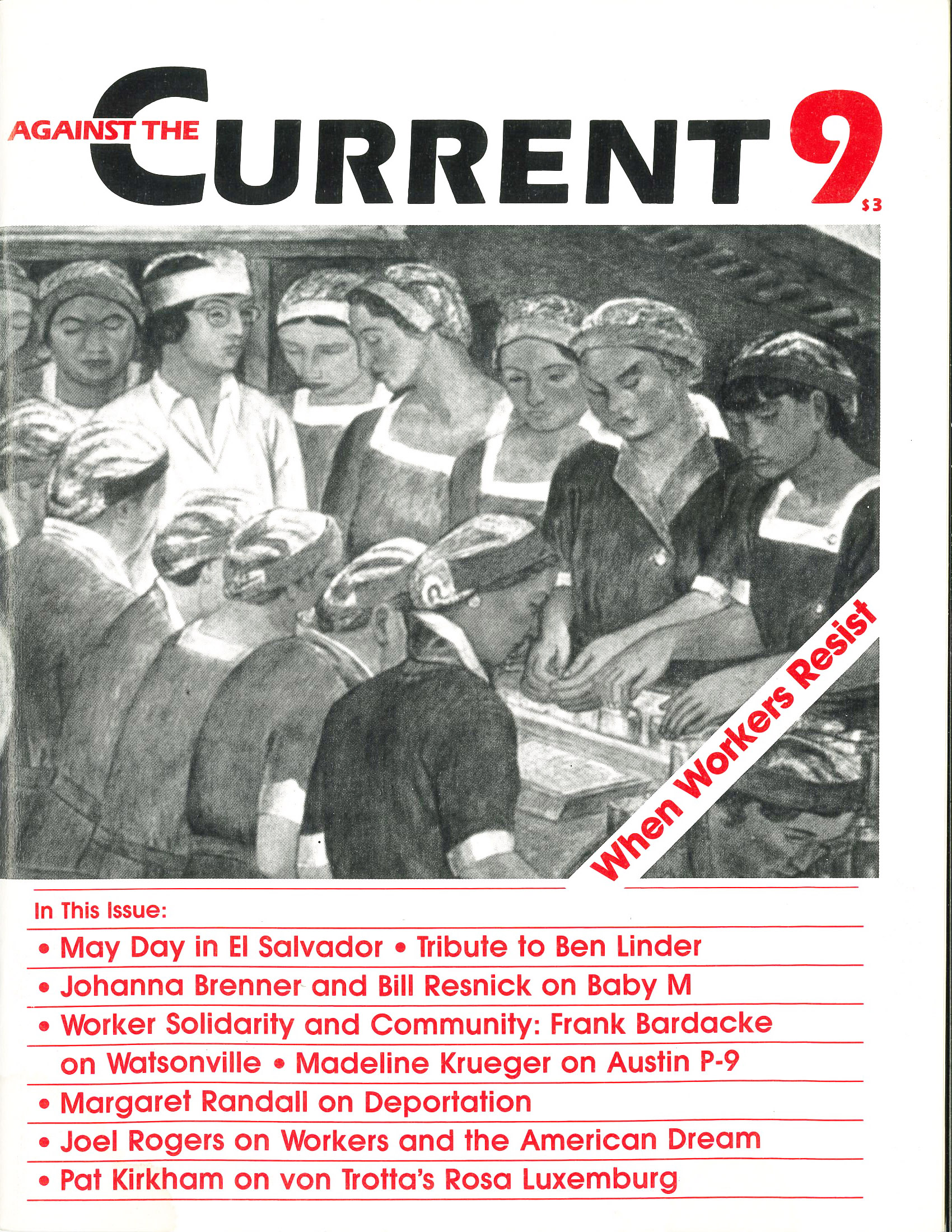

— R,F. Kampfer - When Workers Resist

-

Update on P-9: Concession Battles Continue

— Roger Horowitz -

United Support Group Continues P-9 Fight

— interview with Madeline Krueger -

Watsonville: How the Strikers Won

— Frank Bardacke -

TDU: Ranks Try to Save the Union

— David Sampson -

Imprisoned by a Dream: Will the Giant Awake?

— Joel Rogers - Reviews

-

Technology of Control

— Marty Glaberman -

Capital Relations in Bed

— Lizzie Olesker -

Heilbroner's View of Capitalism

— Howard Brick -

Von Trotta's Rosa Luxemburg

— Pat Kirkham - Dialogue

-

Nicaragua: Debt Crisis & Land Reform

— Carlos M. Vilas -

Response to Carlos M. Vilas

— Ralph Schoenman -

On Democracy & Revolution

— Stanfield Smith -

Response to Stanfield Smith

— Alan Wald -

Stalin-Hitler Pact: Buying Time?

— Joshua P. Kiok -

Response to Joshua P. Kiok

— R.F. Kampfer -

Elections & Revolutionary Politics

— Steve Leigh

Frank Bardacke

THE HAPPY TASK of this article is to explain a major working-class victory, which seven long years after PATCO, surely needs some explaining. Frozen-food workers in Watsonville, California, after an extended eighteen-month strike in which not one striker crossed the picket line, have beaten back a heavily financed attempt to bust their union, and have won full wage and benefit parity with the rest of the frozen food industry.

What happened? Why did the Watsonville strikers win when so many others have lost? Four major factors produced this unexpected victory: (1) it was a small town strike; (2) the strikers were overwhelmingly Mexican and Chicana women; (3) there was an indigenous left presence in the strike; (4) frozen food plants cannot be moved far away from the fields where vegetables are harvested.

Before I get too carried away in enthusiastic analysis, a stern warning. The victory was strictly limited by an earlier defeat; six months after the strike began. The workers at two frozen food plants, Watsonville Canning and Shaw, originally went out on strike together in September 1985. The Shaw strikers, under extreme pressure from the Teamster bureaucrats and unprepared themselves, accepted a sell-out agreement in February 1986. That concessionary agreement dropped wages from $7.06 to $5.85 an hour and cut some benefits. Over the next few months, Sergio Lopez, the secretary-treasurer of Watsonville Teamster Local 912, pushed the settlement throughout the Watsonville frozen-food industry, setting a new standard that the Watsonville Canning strikers could only hope to match, not top. [See “The Battle of the Watsonville Canneries,” interview with Frank Bardacke, ATC #2, March-April 1986.]

Following this all-too-familiar strike defeat, the management of Watsonville Canning refused to sign the concessionary agreement and went all out to bust the weakened union completely. Instead they busted themselves, as the strike was so strong and united that Watsonville Canning could never sustain even minimal levels of production.

Wells Fargo Bank, which over the last two years had financed the bust-the-union/concessionary drive, foreclosed on the Watsonville Canning management (which was nearly $30 million in debt) in January 1987. They found a new buyer for the plant-a vegetable grower, David Gill, who was owed $5 million by Watsonville Canning and came into the deal to try to regain his losses. Wells Fargo and Gill accepted the fact that the strike union contract and immediately began to negotiate with Local 912. Together with the Teamster officials they concocted a further concessionary deal, that granted wage parity but which denied 85% of the workers their medical benefits for three years. When the Teamster bureaucrats tried to sell this one, the strikers turned them down. In the middle of the debate over this proposed agreement, the Teamster officials called the strike off, announced that there would be no more $55 a week strike benefits, and declared the picketing illegal.

The strikers, by now sure of their own strength, tempered and educated by eighteen months of struggle, answered with a powerful four-day wildcat extension of their strike. Gill and the officials were forced back into negotiations where Gill delivered the desired medical plan, making workers eligible for benefits after three months.

But that is the end of the story. It is best to start at the beginning.

The Town

Watsonville is an agricultural town of about 25,000 people sitting in a small valley of apple orchards, strawberry fields, and long rows of vegetable crops squeezed between the Pacific Ocean and the redwoods of the Santa Cruz mountains. The valley, still called Pajaro, the name given it by Cabrillo, is so rich in natural resources that the Indians who lived here before the Spanish came didn’t even need agriculture-they lived off the nuts, berries, birds, salmon and deer. The climate is so mild that the town has become a favored place to retire; we have a large housing development for senior citizens only, and convalescent home/death houses are a growth industry where some Watsonville Canning strikers were “retrained” to work as nurses’ aides.

Two hours by car south of San Francisco, Watsonville sits at the head of the Salinas Valley, the most productive vegetable-growing area in the world, which for six months of the year (from May to October), produces nearly 80% of all the fresh vegetables sold in the United States. It is the Salinas and Pajaro valleys that provide most of the fruit and vegetables packed in the eight Watsonville frozen-food plants, which make the town the self-proclaimed “Frozen Food Capital of the World.” Together they produce about half of all the frozen broccoli, cauliflower, spinach, Brussel sprouts, as well as smaller percentages of several other fruits and vegetables, eaten in the United States.

All these frozen foods are processed by only 4,000 people, working eight-to-ten months a year. The workers are about 80% Mexican and Chicano, overwhelmingly female, and about half speak only Spanish. Taken together, their wages are the biggest paycheck in town, although there are also several thousand farmworkers living in the valley who work in Watsonville and Salinas. The farmworkers are almost entirely Mexican and speak only Spanish. In many families the wife works in the frozen-food plant and the husband works in the fields, creating the foundation for deep unity between farmworkers and cannery workers, or perhaps disunity, as the local joke goes.

Watsonville was the model for the town in John Steinbeck’s morality tale of an apple strike in the 1930s, In Dubious Battle, and since the ’30s Watsonville workers have been a militant core of both farmworker and agricultural-shed worker movements. A Watsonville wildcat sparked the historic and victorious 1969 United Farmworkers (UFW) strike in the Salinas Valley, and even in a period of relative decline the UFW remains stronger in Watsonville and Salinas than anywhere else.

Watsonville, then, is a rural working-class town, an integral part of American agribusiness, not far from large cultural and industrial centers. And, as strike support publicity emphasized, it is a Latino town, with more than 70 % of the public elementary school students Spanish-surnamed (this statistic somewhat overstates the extent of the Mexican and Chicano population as many Anglo families have put their children in private Christian schools). Bilingualism in the schools is an issue that has raged in the community for more than ten years, and the local school district is in a state of perpetual crisis, best demonstrated by the better than two-thirds drop-out rate for Latinos at Watsonville High School.

Even though the community is at least half Mexicano/Chicano there has never been a Chicano member of the City Council. This led to a recent Mexican-American Legal Defense Fund (MALDEF) suit still in the courts-which picked Watsonville and Pomona, California, as test cases, saying that the cities’ at-large elections are unconstitutional because even though they are technically fair they result in discrimination against the Chicano community. The City Council is made up primarily of real-estate interests; agribusiness is so powerful they do not need direct representation.

Anglo working-class culture is weak; there is no large cowboy scene like the one in Salinas. In the “greater” downtown area only the bowling alley and the YMCA remain white working-class places, and over the last few years they have opened up to Chicanos. On Saturday nights Mexicans peacefully shoot pool at the bowling alley, a scene that started many white-brown fights only five years ago. Mexicano/Chicano culture dominates downtown, despite recent attempts to whiten it lip with “historical renovation,” which has meant pretty places to eat (one with a Mexican “flavor”) for the white office workers who work in downtown Watsonville but live (culturally speaking) a million miles away in Santa Cruz or in some very white neighboring communities like Aptos and Corralitos.

A small Chicano petty bourgeoisie in town is based in small business and in the growing number of Chicanos in social services, as well as some lawyers and doctors. There are also a small number of Chicanos who work as foremen, supervisors and secondary management in agribusiness. This petty bourgeoisie ranges from radical to reactionary in its outlook, and has been struggling over the local League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) chapter, recently taken away from the most reactionary elements.

Racism in the town is strong. Many whites, especially long-time residents, blame Mexicans for the change from small town farm community to small but big time agribusiness center and the “problems” that came with it: the housing crisis, the deterioration of the schools, traffic, unemployment and crime. The white racism is mitigated by many Anglo-Mexicano/Chicano friendships at work and at school. Some Anglos and Chicanos become closest friends and there are many Anglo-Chicano marriages, as well as a couple of Anglo-Chicano bars. However, there has never been a bilingual, bicultural voluntary association in town (outside of the PTA groups at the local public schools) until the formation of Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) in 1980.

One last image of the town. A few years ago the electronics industry, whose regional center is only an hour away in San Jose, was seen by the city officials and the real-estate business interests as a way for Watsonville to break away from being a one-industry town and as a key for future development. The City Council gave tax and permit breaks to a Santa Cruz chip-making company to build a new factory on the edge of town. Before it was completed it was obsolete, as all that particular work is now done in Asia. The factory stands finished, ready to run, vacant, viewed from the main freeway entrance into town, a silent testimony to low wages of Asian workers and the irrationality of capitalism.

The Stubborn 1,000

Over the eighteen months of the strike, not one of the 1,000 Watsonville Canning strikers returned to work. This incredible unity, maintained with brutal determination, was the key to the strikers’ ultimate victory. During the course of their almost two-year struggle, several other large strikes broke out in Northern California-among winery workers, TWA flight attendants and Kaiser Hospital workers. In each case a significant number of workers (from 20 %-50 % ) returned to work during the strikes, laying the basis for their defeats. Even in the historic Hormel strike, 200-300 strikers broke ranks and scabbed.

These defections are not just questions of strike morale. When a company can recruit back a significant minority of its workers, those workers together with inexperienced scabs, can restore production to a high enough level to successfully wait out a strike. At Watsonville Canning, throughout the strike, the company could not run its polybag machines, its hemus automatic weighing machines, its automatic fillers, closers, and wrappers. -The whole packaging operation was in a shambles, forcing the company to pack by hand or to bulk pack and send its product to other companies to be repacked.

Consider what this means. Bombarded by an ideology of robots and computers, by our supposed transformation into a nation of service workers, we forget that people are still necessary to produce things. The machines inside factories do not run themselves. Skilled, experienced people set them up, adjust them, and fix them when they break down.

Moreover, there are no exact written directions about how to fix these machines. The mechanics, over time, learn their individual quirks, ignore the official adjusting screw on top and bang the machine in just the right spot on the bottom to keep it going. This knowledge is hardly ever “shared” with supervisory personnel. The workers know its value and guard it jealously. Besides, the supervisor’s job is not to learn how the machinery works, but to pressure the mechanics to keep it working. When all the mechanics went out on strike, the supervisors, management personnel, and even out-of-town experts could not get the plant into good working order.

Nor were the women on the line easy to replace. With help, a raw recruit can become an average broccoli trimmer in a couple of weeks. But that is in the midst of an experienced crew, ready both to teach and to cover for a beginner’s mistakes. And just being able to move your hands skillfully and quickly enough is only a small part of the job. What’s tough is getting there every day, standing on the hard, often wet, concrete for eight-to-twelve-hour shifts, putting up with the deafening noise, the endless, sometimes nauseating movement, of the product on the belt, the constant pressure from the floor ladies, and the chicken-shit company rules.

All of that is tough enough in ordinary times, for what used to be the basic wage of $6.66 an hour, plus medical benefits, and a week’s paid vacation. But when you also have to be bussed in by police escort from another town, or when you return to the parking lot and find your car with four punctured tires, and when you make only $5.05 an hour with no benefits and no job security, then the job becomes very hard indeed.

Typically scabs would work for a few weeks and quit. Over the months of the strike the company was never able to recruit a sufficient number of steady scab workers. Wells Fargo had been willing to finance Watsonville canning’s attempt to bust the union, but not even the tenth biggest bank in the nation and one of the fastest growing financial institutions in the world could save Watsonville Canning from the simple truth that it needed a serious chunk of its regular work force to make the plant run.

The refusal to scab was made at great sacrifice by most workers. Not only did people lose their weekly checks (for most workers around $250 in mid-season); unemployment benefits ended, women had their AFDC taken away, and only a few people got food stamps or other state welfare. Times were especially hard for the single mothers-an incredible 40% of the strikers-and for the many families where both parents were on strike. People had to get by on the $55-a-week strike benefits, the fortnightly food giveaways, the local food bank and other informal help from family, friends and community. Hundreds of people lost whatever savings they had; scores of people lost their homes or whatever else they were buying on time, like furniture and cars. Families were forced to double up and triple up in what already had been crowded conditions. Some people left town altogether, and a few simply lived out of their cars or trucks.

Many people took other jobs, while they continued to picket at night or on the weekends. Most people found part-time work in the fields, men in the apple orchards in the fall of 1985 and 1986, both men and women in the strawberries and bushberries in the spring and summer of 1986. Many women were retrained to be nurses’ aides; some made the trek to Santa Cruz or San Jose to work at low-paying jobs in the electronics industry; and in the fall of 1986 many got work in the other frozen-food plants in town.

No striker scabbed. A few hundred people did regular picket duty-you had to do picket duty or some other work for the strike to collect the $55. Anywhere from fifty to a high of several hundred people attended strategy meetings where they argued over the direction of the strike. And most everyone, on several occasions, attended rallies and demonstrations of strikers and their supporters.

Primary to understanding this remarkable unity is Watsonville’s small town community and people’s consciousness of themselves as Mexican workers. Unlike the winery workers, flight attendants, hospital workers (or scores of other big-city workers), the frozen-food workers all lived and worked in the same community, went to the same churches, had children in the same schools, played and watched soccer games in the same parks. Large numbers of strikers are actually related to each other, members of the same extended families.

The extended families were crucial. In one, the women who found other jobs left their preschool children on the picket line with one of their comadres who picketed during the day. There is no single word in English for comadre. A godmother of a woman’s child is her comadre. It is a crucial relationship, with definite duties and responsibilities, and it ties nuclear families into extended ones. Families were able to help each other (even move in with each other) because they already had close relations and were used to a level of cooperation practically unknown in big-city Anglo culture.

“At least we’ve learned how to survive,” was a common remark made by strikers, as it became clear that Watsonville Canning might never sign a contract. But people already knew how to survive. The rank-and-file food committee, started in the early days of the strike with just the slightest nudge from TDU, not only organized the twice-monthly food giveaways with magnificent efficiency, but provided scores of meals for hundreds and sometimes thousands of strikers and supporters. Nobody had to teach them how to do that. Many women had been feeding large groups of people for a long time.

During the strike the community got even tighter. ‘We found each other,” was another common striker observation. People who had worked beside each other for years developing only casual, at-work friendships now had to rely on each other to survive. Along with the hardships, the increased drinking, and the families that broke under the pressure, there developed deep friendships rooted in mutual need and obligation.

And Watsonville responded. Churches, school teachers, some small businesses and landlords-strike support, organized and unorganized-provided both food and material necessities, as well as an atmosphere of solidarity. Many people were allowed to delay rent payments, others bought on credit at small grocery stores, and many merchants refused to cash scab checks. So many turkeys were donated by the community in the 1985 Thanksgiving turkey drive that after the giveaway of one turkey for each family, the Food Committee had enough frozen turkeys left over to serve turkey enchiladas at strike events months later.

One Chicano mechanic I know explained why he didn’t go back to work. He was not an active striker. Soon after the strike began he got a job as a mechanic in an apple shed where he made less money than he had before and worked only a few months a year. In June 1986 his old supervisor called him up and asked him to come back to work. He, like all other mechanics, was offered a $2,000 bonus, a wage above the official offer of $12.31, and a guarantee that his family would be protected.

I asked him why he didn’t accept.

“Do you think I should go back,” he asked unbelievingly.

“No. I just want to know why you don’t.”

He gave the question some thought.

“There is no way for a striker to cross that picket line and live in Watsonville.”

“Do you mean that you are afraid that people would attack you? Shoot up your home or throw rocks at your kids or something?”

“No. I don’t think anybody would hurt me. But I couldn’t go anywhere in town with my head up, on the chance that I might have to look some striker in the eye. I couldn’t come to this Y, I couldn’t shop at the grocery store, I couldn’t go to the bingo game. For the rest of my life I would be the mechanic who betrayed my people. No money is worth that. I will go back to work at Watsonville Canning with everybody else or not at all.”

The Left

Generally, there were two left campswithin the strike.

Some publications highlighted the differences within the left during the strike. While there were periods when these differences hurt the strike, overall the strike’s success is inconceivable without the conscious radicals, socialists, communists, and rank-and-file militants who provided alternative strategies, ideas and leadership. Without them, the strikers would have been left with only the Teamster officials as leaders, bureaucrats with no idea of how to organize a winning strike.

(1) The League for Revolutionary Struggle (LRS), which worked closely with some militants in the rank-and-file Watsonville Canning Strike Committee; and (2) a more amorphous grouping of independent radicals, militants and Communists (CF) in and around the Watsonville Strike Support Committee, working along with Watsonville Teamsters for a Democratic Union.

These people can hardly be considered “outside agitators.” Some of them were strikers themselves, who had extensive political experience in Mexican student struggles in the late 1960s and in oppositional Mexican union politics in the mid-70s. Others had been members of Local 912, and were long-time Watsonville residents. TDU had been active in the local for five years before the strike began, leading several successful campaigns within the union. And even the people who moved in from out of town had extensive experience working among California food-processing workers or in other Mexican/ Chicano struggles.

The LRS and the Strike Committee played a crucial role in maintaining unity among the workers. They consistently put forward the national character of the fight, emphasizing pride in La Raza and Mexican/ Chicano language and culture. They organized solidarity throughout Northern California through a series of marches, food rallies, forums and a visit to Watsonville by Jesse Jackson. They participated in an extensive campaign to harass strike breakers, which both directly damaged Watsonville Canning and developed and maintained strike morale. And they consistently looked for a middle path that would not alienate the top Teamster leadership, so that the strike did not suffer an attack by the International, which so damaged the Hormel strike.

Looking for the “middle path,” however, often held the strike back, especially in its early days, and was a main difference between this left grouping and the other major left forces, people around the Watsonville Strike Support Committee and Watsonville TDU. The Strike Support Committee and TDU also participated in building local support, raising in Santa Cruz County alone more than $50,000-90% of which went to pay for milk and eggs distributed directly to the strikers. They also organized local rallies, meals, and other strike support events.

But the major contribution of the Strike Support Committee and Watso TDU was that at various times in the strike they pushed beyond the limits of what was being done, helped the workers see the necessity of breaking the ordinary rules of “labor-management” disputes, and supported the rank and file when they disobeyed the top Teamster bureaucrats. It was Watso TDU and the Strike Support Committee who first urged workers to spread word of the strike and who called the first Solidarity March to bust the injunction, despite opposition from all levels of the Teamster bureaucracy. These same folks tried, unsuccessfully, to spread the strike to the fields and other frozen-food plants. They successfully led the drive to make the Wells Fargo boycott something other than just words. And, finally, they led the opposition to the last sell-out proposal by the Teamster bureaucrats, which led to the wildcat that victoriously ended the strike.

Obviously, these roles are somewhat contradictory, and at various times disputes between the two camps were bitter and personal. Moreover, the group around Watso TDU and the Strike Support Committee was in greater contradiction with Teamster Joint Council 7, and the International, and often they were frozen out of meetings or actually banned from the union hall. But in the last few months of the strike the two left groups worked together in something like a principled fashion, as they put forward their sometimes opposing views before the weekly mass meetings of strikers in the union hall, where the strikers made the final choices and decisions.

The Frozen-Food Industry

Crucial to the strikers’ victory was the fact that after the strike had bankrupted Watsonville Canning, Wells Fargo Bank didn’t simply close the plant down and sell off the machinery and equipment. Two factors were primary here. First, frozen food-plants must be close to the fields where vegetables are grown, as quality falls quickly after the crops are harvested. As long as the Salinas and Pajaro Valleys are an important source of fresh vegetables, ancillary frozen-food production will have to remain close by. It is not an option in frozen food to do what a Central Valley canner did, that is, simply pack up a factory and ship it to Mexico, and then truck California tomatoes there to be canned by cheaper Mexican labor.

Secondly, if the Watsonville frozen-food industry is as bad off as the local employers, Teamster officials, and local press have been telling us for the last several years, why didn’t they just let this bankrupt plant fold? The official explanation of the “frozen-food crisis” has varied over the years, with the emphasis shifting between high-energy costs, interest rates, land rent, sewage rates, high-labor cost, and foreign imports, depending on what particular concessions the industry wanted at the time, either from local politicians or their own workers. Taken together these arguments have been used to terrorize the Watsonville community with threats of imminent plant shutdowns. But the fact is that the workers, through their strike, did shut down Watsonville Canning. And the bank and the bosses have done everything possible to start it back up again.

Not that everything is rosy in the industry. It does suffer from serious market stagnation-frozen food is not as popular as it once was with high-income consumers, and it has become too expensive for low-income ones. Over the last several years much of the world-wide investment (including Watsonville) in frozen food has gone into large freezers, the grain silos of the frozen-food industry, where the employers store the food that most people cannot afford to eat.

Nevertheless, this potential crisis has not led to the promised “shakeout” in the industry. Rather, all it has done is intensify the competition between the locally owned plants, all of whom buy from the same growers, run the same labels (that is, produce exactly the same products and brands) and sell on the same market. That market is a tough one, dominated by the big supermarket chains, A&P, Safeway, Alpha Beta, and Lucky’s.

This intensified competition is the real origin of the strike. In 1982, Wats Can broke from the thirty-year-old Frozen Food Employers Association, and got a separate contract from Local 912 officials with a basic wage of $6.66 an hour, forty cents less than what Shaw and the rest of the industry were paying. As soon as that contract expired in 1985 Shaw lowered their wages to the same $6.66, and Watsonville Canning followed by dropping their wages even further. The downward wage spiral was in full force, and a strike was the only way to stop it.

Radical Democracy in the Labor Movement

Learning from our defeats has become the general rule in contemporary labor struggles. In Watsonville people learned from a defeat early in the strike, and then applied what they learned to win a victory at its end. That could not have happened without the development of a radical democracy within the strike, as strike leaders and rank and filers were educated by regular mass meetings, filled with conflict and debate.

This was the crucial difference between the situation in February 1986, when the Shaw workers were forced to accept a sell-out contract, and March 1987, when strikers, despite enormous pressure from the Teamster bureaucracy, turned down further concessions.

After the Shaw and Wats Can Strike Committees were elected in a mass meeting in October 1985, they called no more mass meetings for the next nine months. Rather, they tried to lead the strike through a series of invitation-only meetings with small groups of strikers and union officials. Nor was there time in the large rallies and marches for open debate. Although the strike committees were democratically elected, they did not build a democratic structure into their activity. Thus, at the time of the Shaw vote, the Shaw Strike Committee joined the bureaucrats in saying that the strikers should accept the contract. The committee was separated from the rank and file: they identified with the officials rather than with the strikers. Without any recognized leaders urging a no vote, the Shaw strikers felt that they had no choice but to accept the contract.

By the end of the Watsonville Canning strike this had all changed. The Wats Can Strike Committee started calling mass meetings in the spring of 1986, as they realized that renewed mass participation was the only way to save the strike. By March 1987, after an extended series of struggles, the strike committee was subject to the democratic control of these weekly meetings, rather than being just another bureaucratic formation (albeit democratically elected) claiming to “represent the workers.”

As the top Teamster officials put together their concessionary agreement with the new owner, David Gill, they called the strike committee to San Francisco to “join in the negotiations.” Once there the committee endorsed and celebrated the settlement with their new boss and the Teamster officials at a widely covered press conference.

When the committee returned to Watsonville, however, they were pushed to call a mass meeting of strikers and supporters the night before the official vote, to discuss the agreement. At that meeting of about 150 strike activists the strike committee was convinced to withdraw their endorsement and took no formal position on the contract in the debate the next day. Workers at that night’s meeting agreed to call for a delay in the vote because of the absence of medical benefits in the proposal. They put out their own leaflet, and the strike committee agreed to make no counterstatement. At the formal vote the next day, the activists were united around one demand, and they won by a 3-2 margin.

By this time the rank and file had high confidence in their own strength and organizational abilities. They knew that they could carry on the strike, at least for a short time, without the support of the Teamster bureaucracy. They knew that David Gill, whose spinach was rotting in the fields, was in a greater hurry than they were. During the debate, when Sergio Lopez and Alex Ybarrulaza of Teamster Joint Council 7, declared the strike over, people nevertheless voted to delay a decision, figuring their medical benefits were worth the risk of running the strike themselves for a week.

A couple of hours after the Teamster bureaucrats lost the vote they locked the union hall, which had been opened almost around the clock and was used as the center of rank-and-file activity and meetings. Workers responded by ripping the door off the wall. Then, having made their point about who owned the local, they moved their organizational center away from the hall to a hunger strike that was being held in a strike supporter’s yard across from Watsonville Canning. From that new center they organized their successful wildcat.

March-April 2023, ATC 9