Against the Current, No. 9, May/June 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Baby M, Family Love & the Market in Women

— Johanna Brenner & Bill Resnick -

A Life Worth Living: Benjamin Linder, 1959-87

— Alan Wald -

El Salvador: Popular Movement Gains

— David Finkel -

A Personal Account: Awaiting Deportation

— Margaret Randall -

Comment from Margaret Randall

— Margaret Randall -

Random Shots: Ghosts in the Machine

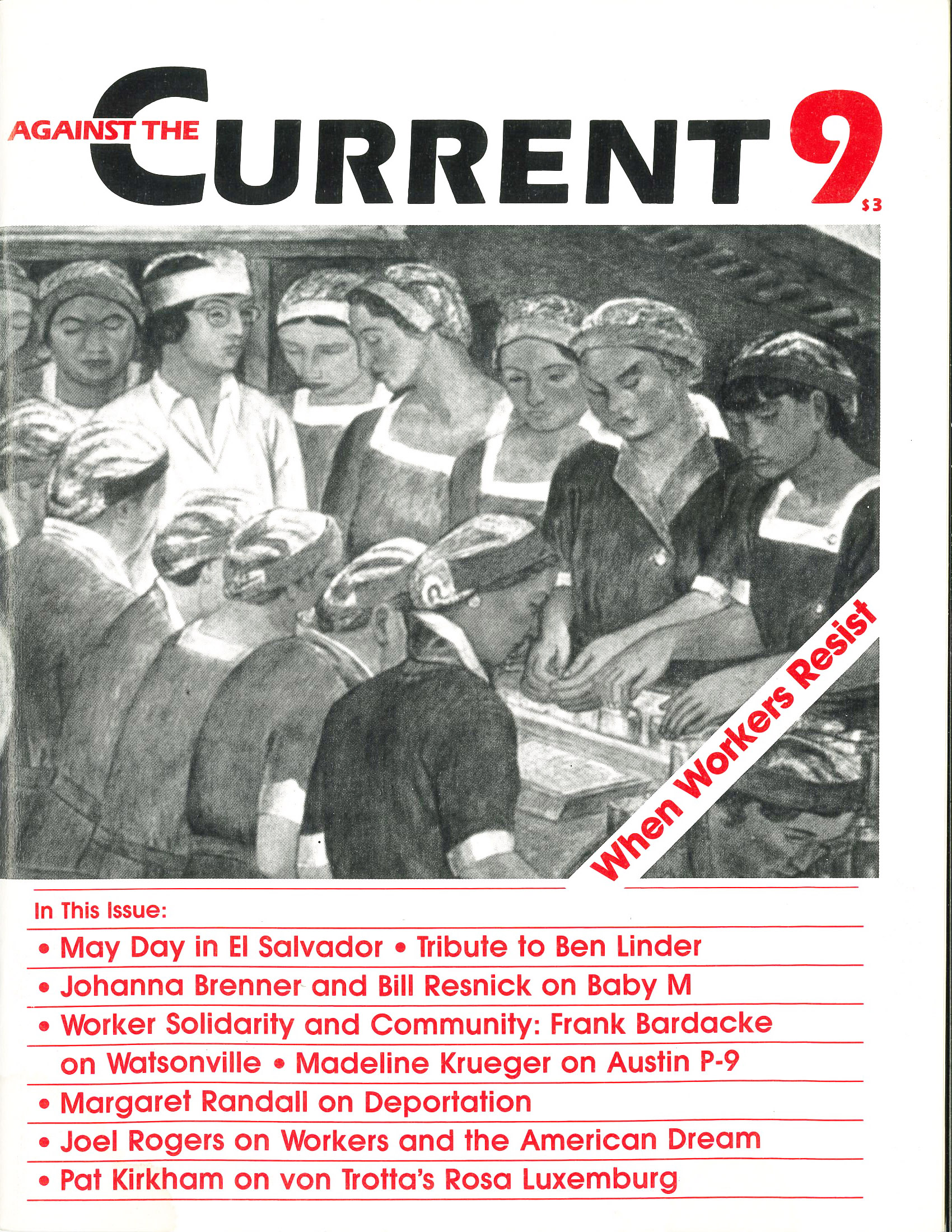

— R,F. Kampfer - When Workers Resist

-

Update on P-9: Concession Battles Continue

— Roger Horowitz -

United Support Group Continues P-9 Fight

— interview with Madeline Krueger -

Watsonville: How the Strikers Won

— Frank Bardacke -

TDU: Ranks Try to Save the Union

— David Sampson -

Imprisoned by a Dream: Will the Giant Awake?

— Joel Rogers - Reviews

-

Technology of Control

— Marty Glaberman -

Capital Relations in Bed

— Lizzie Olesker -

Heilbroner's View of Capitalism

— Howard Brick -

Von Trotta's Rosa Luxemburg

— Pat Kirkham - Dialogue

-

Nicaragua: Debt Crisis & Land Reform

— Carlos M. Vilas -

Response to Carlos M. Vilas

— Ralph Schoenman -

On Democracy & Revolution

— Stanfield Smith -

Response to Stanfield Smith

— Alan Wald -

Stalin-Hitler Pact: Buying Time?

— Joshua P. Kiok -

Response to Joshua P. Kiok

— R.F. Kampfer -

Elections & Revolutionary Politics

— Steve Leigh

Pat Kirkham

Rosa Luxemburg

Written and directed by Margarethe von Trotta

In German and Polish with English subtitles, released by New Yorker Films.

Running time: 122 minutes.

THE FILM ROSA LUXEMBURG recently opened in New York City and elsewhere in the United States. Luxemburg is one of the few well-known female Marxist theoreticians and activists, standing alongside Lenin, Trotsky, and in deed Marx himself, in a roll call of those who have made an outstanding contribution to Marxist ideas and dedicated their lives to socialism. Born in Poland (then part of Tsarist Russia) in 1871 into a Jewish family, she worked ceaselessly for proletarian revolution from her student years until her brutal murder by counter-revolutionary forces in Germany in 1919.

It is a rare treat to see a beautifully made, compelling, and thought-provoking movie about one of the world’s greatest revolutionary socialists. Margaretha von Trotta, one of West Germany’s best-known film directors, has previously directed movies concerned with female characters and feminist issues.

In this instance, von Trotta spent eighteen months researching her heroine and, in the end, felt she knew as much about Luxemburg as anyone-with the exception of a few historians. No doubt she does at one level, but my doubts about the film rest mainly on questions of understanding and interpretation; space does not permit an evaluation of the construction of the film itself.

Simply put, von Trotta’s view of Luxemburg diverges considerably from the views of some revolutionary socialists who have studied the same material. Clearly her film tells us a great deal about Rosa the woman (and that is important; I disagree with those who feel that the presentation of non-political aspects of Luxemburg’s life, such as her love of her cat, Mimi, trivialize a great revolutionary), but this approach does not leave us with an understanding of the political woman.

Indeed, there is no clear exposition. of Luxemburg’s politics in the film. Unless one takes to the film an already theorized position and an historical understanding, it is all too easy to see Luxemburg as a passionate idealist and feel (as von Trotta seems to) that her ideas would never have worked anyway.

Von Trotta’s Pessimism

From a socialist perspective this is a deeply pessimistic film. Von Trotta goes beyond an acknowledgment of the sheer strength of forces weighed against revolutionary change, to a fundamental pessimism about future activity which may directly reflect her own doubts. This pessimism is at odds with all for which Luxemburg stood; this means that for me, at least, von Trotta has not managed to capture and convey the essence of Luxemburg in her film.

While Luxemburg knew moments of personal and political despair (which are often beautifully depicted in the film), she remained resolutely optimistic about the revolutionary potential of the working class and of the situation in which she worked. One cannot expect a film to give a blow-by-blow account of her revolutionary activity, or to confront the audience with political text after text; but I had hoped for a distillation of a great revolutionary woman which would inspire others.

Humanizing Rosa

The real strength of Rosa Luxemburg lies in its effort to humanize Luxemburg herself. It is only in West Germany that the full force of feeling against Luxemburg can be understood and, likewise, von Trotta’s need to counteract the “bad” image with a “good” one. In her other films, she has counterpoised opposing aspects of women by locating them in two main characters; in Rosa Luxemburg there is only one woman and some have found the depiction too uncritical. The opposition in this case comes not from within the film, but in von Trotta’s posing of an alternative view to this “bete noir” of German history.

Elsewhere in Europe and in the United States it is difficult to imagine the hatred and hostile emotions stirred by mention of “Bloody Rosa.” This founder of the German Communist Party has been disparaged as a violent madwoman by the conservative right, hated by the Nazis because she was both Jew and communist, disowned by social democracy, and labelled a Trotskyist by the Stalinists. In the early 1970s, some West German postal workers went so far as to refuse to frank postage stamps bearing Luxemburg’s picture, while the proposal for such a stamp itself caused a public outcry.

It is against such views and the current clamping down on radical ideas that von Trotta’s consuming desire to show Luxemburg, above all else as a human being brimming over with a deep love of humanity, must be considered. First and foremost von Trotta’s film is an exercise in humanizing “Bloody Rosa:” she is depicted as an ordinary person like you and me, and yet, at the same time, an extraordinary person.

In particular, she is humanized by being shown as a sweet, bright child; loving flowers and animals, particularly birds and cats; wanting children and a deeply satisfying emotional relationship with her main lover and comrade, Leo Jogiches; having close, warm relationships with her women friends; acting as the perfect aunt; suffering grief when friends and comrades die; and feeling all the strains and cracks in the mind that we all would if shut up in prison.

But above all she is shown as someone who laughed, cried, got angry, danced and made love, just like the rest of us. Integral to this is her very deep humanity, her concern for what Marx called the full and free development of every individual. This informs von Trotta’s film and makes parts of it memorable. She manages to convey the depth of Luxemburg’s feeling for others-for the suffering of all living things-that comes through in Luxemburg’s writings, particularly in her letters.

Barbara Sukowa as Rosa Luxemburg

So well did Barbara Sukowa play the many sides of Rosa Luxemburg-the strong and angry as well as the caring and loving woman that she was awarded the “Best Actress” award at the 1986 Cannes Film Festival. Well known in West Germany (and elsewhere for her portrayal of the terrorist based on Gudrun Ensslin of Baader-Meinhof in Mariane and Juliane/The German Sisters, 1981), the choice of Sukowa enhances von Trotta’s task of humanizing the image of Rosa Luxemburg by presenting a “star” persona.

Yet some people consider that this has resulted in too glamorous a picture of Rosa Luxemburg. I do not feel that Luxemburg is deliberately glamorized as such in the film (an obvious temptation when attempting to get an audience to sympathize with a female character) but I do think it should be acknowledged that Sukowa is more stereotypically “beautiful” than was Luxemburg.

It was possibly to distance the film from such problems — and partly to obtain a female lead close in ethnic origins to the heroine — that von Trotta initially attempted to find a German-speaking Polish/Jewish actress to play the part.

She visited Poland where she not only had difficulty finding someone satisfactory but also anyone willing to play the part of a woman who, although officially acknowledged, is regarded with considerable hostility. Indeed, attitudes were so anti-Luxemburg that one film director suggested von Trotta should leave Luxemburg dead in the Landwehr canal!

Had von Trotta found a suitable actress she would have been able to foreground Luxemburg’s Jewishness, and show how Luxemburg in her political work had to contend with anti-Semitic attitudes. As it is, the issue is left untouched in the film.

A Film of the 1980s

The narrative of this biographical picture is cut up by von Trotta’s favored mechanism of flashbacks which, as in her earlier films, are not in chronological sequence. This causes some confusion for viewers unfamiliar with the detailed history of European revolutionary and social democratic politics circa 1890-1919 as well as the biographical details of Luxemburg herself-and that means most audiences.

On first viewing one is constantly asking oneself which prison is she in now? How can she be involved in the 1905 Russian Revolution if she is in Poland? Which Karl are they referring to now? Is that Kautsky or Bebel she is dancing with? This is a major fault in an historical film, especially one such as this where the director hoped the “period” feel would fade into the background.

Although set in the years 1871-1919, the film raises issues of the 1980s, mainly sexual politics and the contemporary antiwar movement, and thus tells us a great deal about von Trotta’s own politics and concerns. She claims to have had enough material for two films, so her choices of omission are as significant as her choices of inclusion and emphasis.

Consequently, it may be helpful to locate this film in the context of von Trotta’s own particular view of West German politics and culture. Von Trotta is at her best when dealing with the issues of feminism and the antiwar movement, the two broad-based campaigns of the German left and liberals today.

Yet it was as a radical in 1968 that von Trotta first came across Luxemburg as a face on a banner carried during the student demonstrations. She found it uplifting, as did so many of us, to see a woman up there wafting in the breeze with Marx, Lenin, Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh. Since then, von Trotta had aspired to make a film about her. But had the film actually been made then, there might have been a greater stress on imperialism and international revolutionary ferment; in the rnid-1980s, however, the stress is on feminism and antimilitarism.

So at one level, this film might be read as a measure of the extent to which German student radicals of the late 1960s and early 1970s have shifted from more explicitly revolutionary perspectives to a narrower fixation on Green peace and feminism.

Luxemburg & the “Woman Question”

While exploring the hypocrisy of the male leadership of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) on woman’s liberation, von Trotta introduces but does not explore the criticism that Luxemburg did not put sufficient effort into the women’s section of the party. The issue is raised presumably because von Trotta knows that Luxemburg is often presented within the women’s movement as someone who was not interested in feminism or in the separate organization of women, within or outside the party.

These are major issues for socialist feminists today and ones with vital repercussions for the operation of socialist groups and parties. Von Trotta shows how, in her own supremely confident way, Luxemburg can take on the best of the male comrades (as she did Lenin later on) — but where does that leave other women?

The film chooses not to detail Luxemburg’s work for the women’s paper or her work around the women’s suffrage issue but rather builds — through short scenes and comments — a picture of her as a feminist. In other words, while acknowledging that at the time Luxemburg might not have considered herself a feminist (because she was always stressing how the woman question was only one battle, which together with the battles against reformism, antimilitarism, etc. had to be fought in a wider revolutionary struggle), the film reveals to us that nevertheless she was one.

Luxemburg in Prison

The prison scenes, one of which opens the film, are central. They result from the huge impact made on von Trotta by the letters Luxemburg wrote from prison and provide a key to von Trotta’s understanding of her heroine. It is in these letters that one finds most about the “other” Luxemburg: the would-be botanist, the lover of literature and drawing, the introspective woman. They are compelling reading and von Trotta manages to translate certain passages of Luxemburg’s prose into equally compelling visual images.

The most remarkable of these depicts her in a caged structure inside the Warsaw citadel prison in 1907 when she is visited by her brother. The grid-like form and abstract shapes of the cages strongly suggest the captivity of an animal. Writing to Sonya Liebknecht from the Wronke prison ten years later, Luxemburg recalled the

“… regular cage consisting of two layers of wire mesh; or rather a small cage stands freely inside a larger one, and the prisoner only sees the visitor through this double trellis-work. It was just at the end of a six day hunger strike, and I was so weak that the commanding officer of the fortress had almost to carry me into the visitors’ room. I had to hold on with both hands to the wire of the cage, and this must certainly have strengthened the resemblance to a wild beast in the zoo.

“The cage was standing in a rather dark corner of the room, and my brother pressed his face against the wires. ‘Where are you?” he kept on asking, continually wiping away the tears that clouded his glasses. How glad I should be if I could only take Karl’s [Liebknecht’s] place in the cage of Luckau prison, so as to save him from such an ordeal.”(1)

Prison shows an “other” Luxemburg outside the personal and the political Luxemburgs depicted in the film. It allows von Trotta to show Luxemburg alone and it is significant that the film ends with Luxemburg again alone, this time in the canal. This Luxemburg is the patient, suffering Luxemburg; indeed, the film was originally called The Serene Patience of Rosa Luxemburg (until the distributors changed it on the grounds that it would put off potential customers).

Yet Luxemburg’s patience was part of her revolutionary practice; it was exercised when it had to be. This is shown clearly in the film when, in 1918, the prison governor congratulates Dr. Luxemburg in having been a “model” prisoner and expresses his surprise at her patience.

Her reply is simple: “I needed all my patience to survive.” She then gets extremely angry. Here is the opportunity she has been waiting for-the war is over and serious agitational and organizing work needs to be done-but she is ill in prison. She demands her freedom in a splendidly angry and most impatient manner that rocks the audience as well as the prison governor.

Children, Domesticity & Love

Although the film poses many positive feminist viewpoints, the scenes relating to Luxemburg’s relationship to Leo Jogiches are problematic. Von Trotta never clearly conveys the nuances of their complex relationship and it is all too easy to read Luxemburg’s yearnings for children, a home and marriage to a loving sexual partner within contemporary bourgeois ideology, be it of 1907 or 1987. Here is a chance missed for depicting the real interlocking of the personal and the political in Rosa Luxemburg. As Tim Mason writes in his illuminating article, “Comrade and Lover,”

“No one…has ever put the problems of equality, dependence and individual development in a love relationship between comrades in anything like the same precision as Luxemburg did with Jogiches ….She wanted, and was sure she could create with Jogiches, a full and comprehensive union which would fuse passions, intellect, mutual analysis, child-rearing, caring for aged and sick relations, and the politics of socialism, a union which would combine a loving home and shared revolutionary struggle.

“By god, no other couple has a task like ours; to shape a human being out of each other.” (July 1900)(2)

Luxemburg is shown throughout the film as loving children and being good with them, be it singing and talking to her niece or playing with the Kautsky kids.

This makes the short scene in which Jogiches refuses to have children even more touching, as it forces Luxemburg to sacrifice this for her politics and her relationship with him. Steeped in the harsh realities of life underground and mindful of the difficulties having a child would mean for them, he argues that “…a child makes you scared” and told Rosa that her task was to give birth to ideas-“they are your children.”

His decision restricted her to this, but she was convinced that all the difficulties of their life together could be overcome-if only by their (well, mainly her) almost superhuman will. Her position was that, despite all the oppressive social conventions of the day and despite her own belief that the “woman question” could only be solved under socialism, revolutionary women and men could work out new social relationships and remain political activists.

Because van Trotta does not make this position crystal clear in the film, it is easy to build up a picture of Luxemburg as tempted away from “hard” politics to the “softer” side of life, to domesticity and children. The scenes about children link up with others which emphasize Luxemburg’s pleasure in a neat and tidy domestic environment and her desire for a “real home” with books and a library (understandable enough in a life which included exile and prison).

Given that many people on the left today see these issues as oppositions-because they feel or have experienced that one does not provide space for the other, and have children and build nice homes when they retreat from socialist politics-the film is raising a key theme of the 1980s. It is significant, however, that von Trotta does not emphasize Luxemburg’s own stress on the combination of revolutionary activity and domestic happiness but presents one set of her desires as in opposition to another, i.e. the personal to the political.

At no stage does the film argue that it is possible and desirable for a woman to be partner /wife and revolutionary at the same time.

Politics, History & Film

The very complexity of the period of revolutionary upheaval depicted in the ending of Rosa Luxemburg raises the question of how to convey politics and history in film. Notwithstanding the many faults of Warren Beatty’s movie Reds (and one of them was its drift into a love story, something von Trotta studiously avoids), it retains enough of Trevor Griffiths’ dialogue to successfully convey political ideas through the cut and thrust of fierce political debates within a socialist party. It also attempted to locate, and thereby understand, the main character in an historical setting. Thus the enormous uplift in spirits given to John Reed by events in Russia is there in the film. Von Trotta, by contrast, ignores the Russian Revolution even though it is central to any understanding of the German Revolution. Although directly inspired by the success of the Russian Revolution, the German Revolution has a miraculous virgin birth in Von Trotta’s film.

Von Trotta’s approach is to introduce history and politics by including contemporary newsreel film of mass demonstrations and street battles, which are interspersed with somewhat unconvincing scenes of the uprising, particularly of a barricade scene. Overall, the effect is more confusing than illuminating.

The film sides with Luxemburg over the issue of the premature uprising but this is largely achieved by the fact that she is already the central sympathetic figure in the film and because Liebknecht, at this stage, is portrayed as a wide-eyed ultraleftist running around with red flags. It is true that the audience hears some of Luxemburg’s fiery newspaper editorials, but politics and history are subordinated to the personal focus on the individual to the extent that, in the end, it is Luxemburg’s tiredness and illness that sticks in the mind.

The German Revolution is of vital importance because it is the closest to working-class revolution that an “advanced” industrial country has ever come and therefore has many lessons for today. It is regrettable that von Trotta’s depiction of it is flimsy.

Her decision to omit any references to the Russian Revolution also denies the central character what was one of the most uplifting moments of her entire life-news of the workers revolution in Russia.

In the film Luxemburg’s political hopes end with her body dumped into a canal. It all appears inevitable, fatal even, that this remarkable woman who has suffered so much should meet such a dreadful death. Von Trotta has said that the brief flicker of light over the canal suggests there is some hope for the future-but there is no way in which this last shot in the film is an optimistic one.

Von Trotta leaves us there. But was this the end of Rosa Luxemburg, of her ideas? It is significant that no epilogue is added to show her influence today. Nor is Von Trotta’s favored flashback technique used here, as it was earlier in the film to show scenes such as that in which Luxemburg comforts Sonya Liebknecht, who despairs that the war will never end. She tells her they will live on to see great things and reminds her of the mole which patiently burrowed and burrowed away until it undermined everything around it.

Notes

- Letter from Prison, Wronke, February 18, 1917, in Rosa Luxemburg Speaks, edited by Mary-Alice Waters, New York, Pathfinder Press, 1970, 333.

back to text - Tim Mason, “Comrade and Lover: Rosa Luxemburg’s Letters to Leo Jogiches,” History Workshop, Issue 13, Spring 1982, 96.

back to text

I am grateful to Michael O’Shaughnessy for viewing and discussing this film (and many others) with me and for his comments on the text.

May-June 1987, ATC 9