Against the Current, No. 9, May/June 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Baby M, Family Love & the Market in Women

— Johanna Brenner & Bill Resnick -

A Life Worth Living: Benjamin Linder, 1959-87

— Alan Wald -

El Salvador: Popular Movement Gains

— David Finkel -

A Personal Account: Awaiting Deportation

— Margaret Randall -

Comment from Margaret Randall

— Margaret Randall -

Random Shots: Ghosts in the Machine

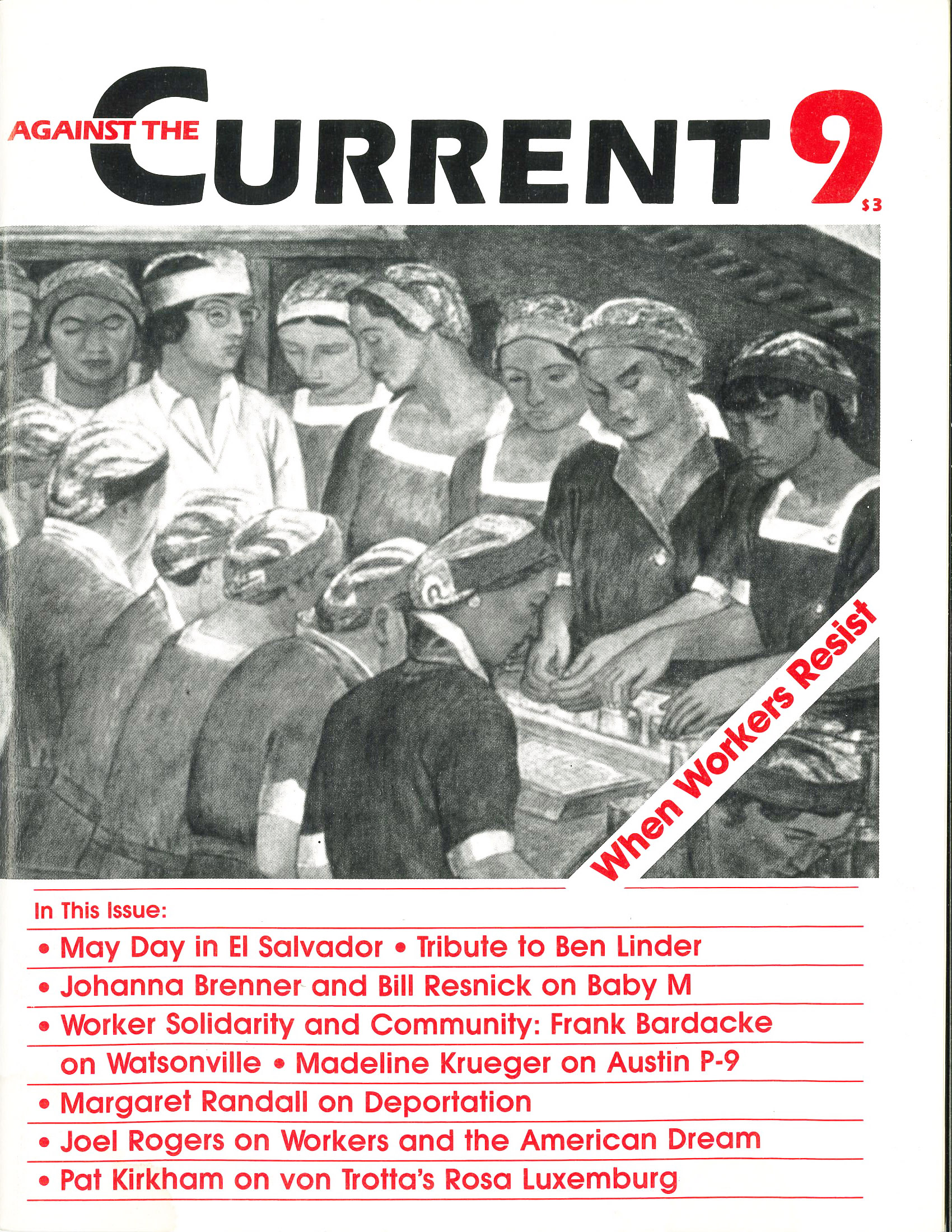

— R,F. Kampfer - When Workers Resist

-

Update on P-9: Concession Battles Continue

— Roger Horowitz -

United Support Group Continues P-9 Fight

— interview with Madeline Krueger -

Watsonville: How the Strikers Won

— Frank Bardacke -

TDU: Ranks Try to Save the Union

— David Sampson -

Imprisoned by a Dream: Will the Giant Awake?

— Joel Rogers - Reviews

-

Technology of Control

— Marty Glaberman -

Capital Relations in Bed

— Lizzie Olesker -

Heilbroner's View of Capitalism

— Howard Brick -

Von Trotta's Rosa Luxemburg

— Pat Kirkham - Dialogue

-

Nicaragua: Debt Crisis & Land Reform

— Carlos M. Vilas -

Response to Carlos M. Vilas

— Ralph Schoenman -

On Democracy & Revolution

— Stanfield Smith -

Response to Stanfield Smith

— Alan Wald -

Stalin-Hitler Pact: Buying Time?

— Joshua P. Kiok -

Response to Joshua P. Kiok

— R.F. Kampfer -

Elections & Revolutionary Politics

— Steve Leigh

Alan Wald

DOES STANFIELD SMITH have a convincing case for his claim that my critique of the FSLN is “liberal anti-communist”?

The phrase “liberal anti-communism” refers to a view widely held by U.S. intellectuals after the post-World War II years. Its basic tenet is that the dangers of Soviet expansionism are so enormous that one must give “critical support” to U.S. imperialism (usually referred to as “the West”) when Third World countries struggle to free themselves from the exploitation of the more advanced capitalist nations.

But my essay ca1ls for the military defeat of U.S. imperialism. It also argues that the FSLN merits “political support” as a revolutionary organization.

Smith is able to make such a wildly misleading claim only by basing his case on political views erroneously attributed to me and expressed nowhere in my essay. Among the opinions he invents for me are the following, that the USSR should refuse to aid developing nations; that the FSLN should abjure friendly relations with the USSR and declare its government “illegitimate;” that the FSLN should respond to Cuban support by criticizing the Cubans; that knowledge of the Stalin-Trotsky struggle “is the criterion of knowledge of revolutionary theory in 1986;” that the FSLN should take positions tantamount to support of the “Afghan contras;” and that the “most important question for a Sandinista … is to attack Stalinism.”

I am able to find only two areas in which Smith’s characterizations of our differences are remotely accurate. First, there is his observation that I am concerned about “democratic forms.”

Here I must confess that, while I have polemicized against abstract notions of democracy devoid of class and social context, I also hold that institutionalized workers’ democracy from below, a multi-party political system, and freedom of political expression must complement the economic and social gains of an authentic socialist society.

It is only through the actual appearance of such “forms” that one can measure the degree to which democratic “content” is an integral part of a social formation.

As far as I can tell, both democratic forms and content remain the goals of many members of the FSLN. This is in spite of the horrendous pressure of the U.S.-backed contra invasion that has forced the FSLN government to decree a “state of emergency” and to suspend portions of Nicaragua’s excellent new constitution. How is it possible that Smith, unlike the Sandinistas, can sneer at such concerns at this late date in the history of revolutionary movements?

The second area in which Smith is roughly accurate — although he labors arduously to twist the meaning of my words in all sorts of peculiar ways is in regard to my opinion that the political education of Nicaraguans in Soviet ideology could be deleterious to the revolutionary process.

I simply do not see how the training of FSLN cadres in such disgraceful Soviet practices as the falsification of history, the transformation of dialectical materialism into a vulgar state religion, the advocacy of a “stage theory” of revolution, the justification of one-party rule, the fostering of a materially-privileged caste that usurps political power from the workers and peasants, the institution of forced labor camps for political dissidents, and, of course, the subordination of the political interests of the world revolution (in this case, specifically the Nicaraguan revolution) to the needs of the Soviet ruling group, will advance the Nicaraguan revolution one iota.

The Nicaraguans have every right to accept Soviet military and material aid. But these usually do not come without a political price. That is why I feel that the FSLN membership might be assisted in avoiding political corruption and in maintaining the revolutionary outlook they have already shown through an understanding of classical Marxism and the history of other revolutions. Nothing in my essay implies that the FSLN leaders should start making public denunciations of the Soviet Union, especially when the guns of U.S. imperialism are pointed at their heads.

Smith seems to feel that it is a feature peculiar to what he calls ‘Trotskyism” to evaluate revolutionary experiences according to some vision of a socialist society, based on a study of past successes and failures. How else does one evaluate historical experience, if not by a scientific projection of its potential development? How can we judge a society to be sexist or racist or exploitative without some sort of concept of a non-sexist, racist or exploitative society-even though one has never truly existed?

What is important in making such judgments is that one’s expectations be realistic for a given context and moment in history; that one’s perspective be evenly balanced between strengths and weaknesses of a political leadership’s theory and practice; and that one maintain an ability to distinguish between a complex process that has multiple tendencies operating within it, and one that has reached some sort of profound impasse.

May-June 1987–ATC 9