Against the Current, No. 9, May/June 1987

-

Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

Baby M, Family Love & the Market in Women

— Johanna Brenner & Bill Resnick -

A Life Worth Living: Benjamin Linder, 1959-87

— Alan Wald -

El Salvador: Popular Movement Gains

— David Finkel -

A Personal Account: Awaiting Deportation

— Margaret Randall -

Comment from Margaret Randall

— Margaret Randall -

Random Shots: Ghosts in the Machine

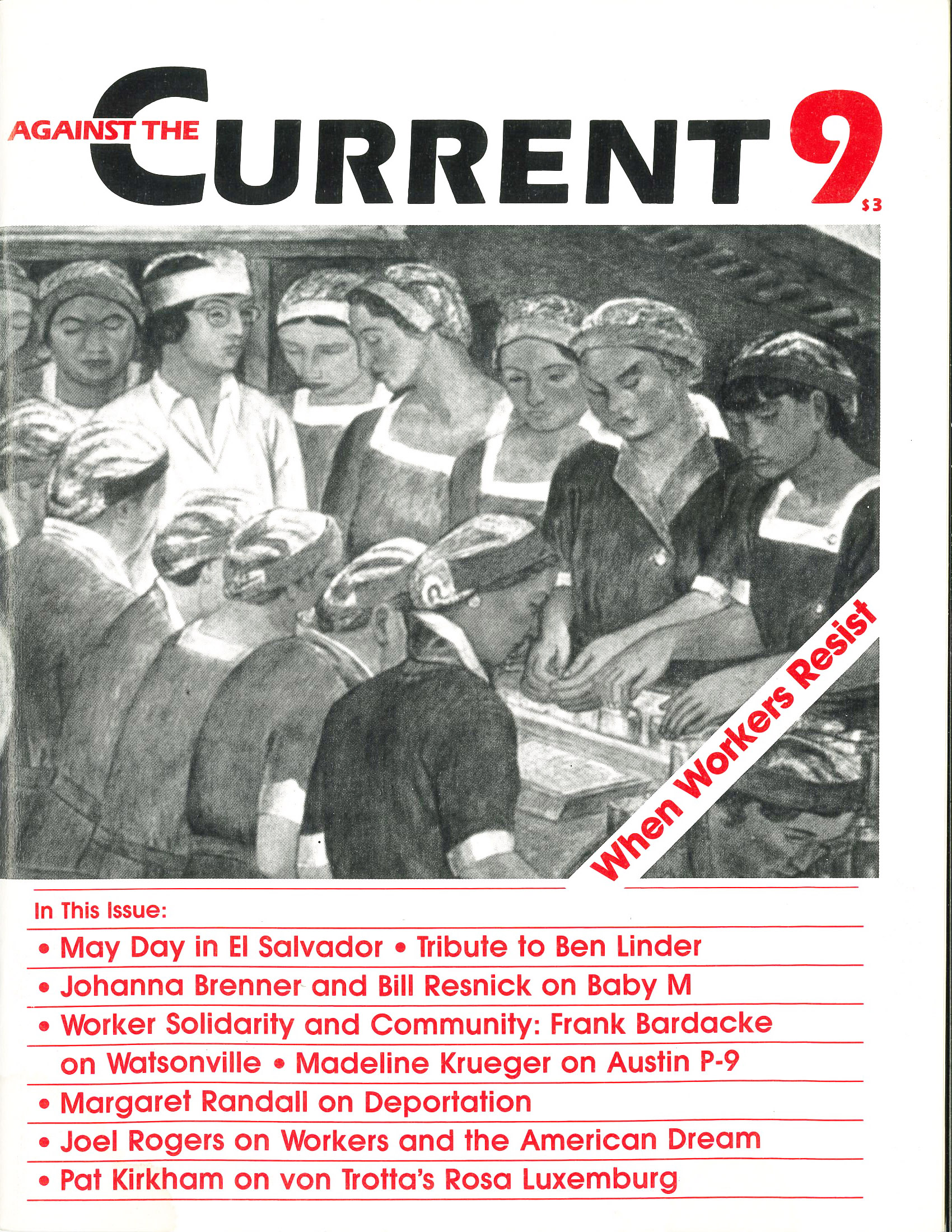

— R,F. Kampfer - When Workers Resist

-

Update on P-9: Concession Battles Continue

— Roger Horowitz -

United Support Group Continues P-9 Fight

— interview with Madeline Krueger -

Watsonville: How the Strikers Won

— Frank Bardacke -

TDU: Ranks Try to Save the Union

— David Sampson -

Imprisoned by a Dream: Will the Giant Awake?

— Joel Rogers - Reviews

-

Technology of Control

— Marty Glaberman -

Capital Relations in Bed

— Lizzie Olesker -

Heilbroner's View of Capitalism

— Howard Brick -

Von Trotta's Rosa Luxemburg

— Pat Kirkham - Dialogue

-

Nicaragua: Debt Crisis & Land Reform

— Carlos M. Vilas -

Response to Carlos M. Vilas

— Ralph Schoenman -

On Democracy & Revolution

— Stanfield Smith -

Response to Stanfield Smith

— Alan Wald -

Stalin-Hitler Pact: Buying Time?

— Joshua P. Kiok -

Response to Joshua P. Kiok

— R.F. Kampfer -

Elections & Revolutionary Politics

— Steve Leigh

Steve Leigh

THE ARTICLES IN ISSUE #4-5 of ATC on independent political action (IPA) and the Sanders campaign for governor of Vermont raised an important issue for the revolutionary left: “Can the left use bourgeois elections, and if so, how?” The writers of the articles in ATC #4-5, Dianne Feeley and David Finkel in one, and Robert Brenner, Warren Montag and Charlie Post in another, argue for a strategy of independent political action: calling for electoral campaigns independent of, and to the left of, the Democratic Party. This, they feel, is an important step in breaking people away from capitalist politics. This article will examine whether this is the best strategy for revolutionary socialists to pursue and will argue that their position of support for IPA in general and Sanders in particular does not contribute to their goal of revolution.

Before explaining the disagreement with their strategy, here are some points we do agree on: 1) Capitalism cannot be gradually reformed into socialism. 2) The Democratic Party is a bulwark of capitalism. Strategies that try to reform it are ineffective and counterproductive for the left. 3) It is important to find a way to break people from the Democratic Party. In this article, I will first look at why reforming the Democrats will not work. After that, I will examine the following: the source of reforms, the strategy of electoralism, early Socialist Party electoralism, the Peace and Freedom Party, the Sanders Campaign, IPA, a revolutionary approach to elections and a revolutionary strategy.

The Democratic Party

The Democratic Party is only the liberal (and often not so liberal) face of American capitalism. It has been the graveyard of movement after movement. A key strategy of the capitalists for defusing social crisis has been to get people off the street and into the election booth, to stop striking and start voting, to quit challenging the system from without and instead work from within. The idea has been to regain loyalty to capitalism by getting movements to accept the legitimacy and effectiveness of legal/electoral methods. As a liberal capitalist party, the Democrats have been ideal for this taming function.

Thus, the goal of IPA, breaking people from the Democratic Party, is a necessary one. However, it is only part of the larger goal of winning people away from capitalist politics in general. The question is whether it is the best strategy to meet this larger goal.

The key determinant of reforms is not what party or person holds office but the balance of social (primarily class) forces. Capitalists will only grant reforms that hurt their profit or power if they feel they have to do so. It is mass action or the fear of potential mass action that brings reform. This is why all major reforms in U.S. history can be traced to specific mass movements and the resulting balance of class forces. This is why a key political goal of the state is to coopt and defuse mass opposition and hence shift the balance of class forces in their direction. This is why the Democratic Party has been so important a tool and why any strategy that lends any support to it is counterproductive.

This analysis has another implication which is disturbing for IPA as well, however; a key strategy of the capitalists is to defuse mass action by getting movements to focus on legalistic strategies such as court suits, lobbying, and electing candidates to office, Even an orientation toward independent “noncapitalist” parties can encourage movements in this legalistic/electoralist direction and thus make them less of a threat and hence less effective.

The Strategy of Electoralism

A strategy of trying to win elections (electoralism) is profoundly conservative for several reasons even for a “socialist” party. To win an election in most periods a party must compromise its politics. It must stress reforms that will carry a majority of votes. Since the left is presumed to already support it, the pressure is to move to the center to attract moderate voters.

Electoralism inherently tends towards reformism. Winning office cannot make a revolution as we know. Any socialist who wins executive office or a party that wins a majority of legislative office will be forced to administer capitalism and therefore lose its socialist politics. It has no choice — unless it declares an end to capitalism and the smashing of the state. If it does this it will be thrown out of office and achieve nothing for its constituents. So the pressure is great after all the work of getting elected to stay in and try to win some reforms by accommodating to capitalism.

Of course, revolutionary parties with a clear perspective can and have run candidates to build the party and spread revolutionary ideas. However, it takes an extremely hard and clear set of politics to make this work without moving toward reformism. If the politics of the party are not rock hard, party members begin to ask “If we put so much energy into running for office, shouldn’t we try to win?” Once the goal is actually to win office, the road to reformism is open and clear.

Early Socialist Party Electoralism

The dangers of an electoralist orientation is also clear in U.S. history. The Socialist Party (SP) in the early 1900s was not at first dominated by the reformist right wing. Instead, for the first few years it was dominated by an almost undifferentiated center/left bloc.(1) The left supported industrial unionism and militancy. Neither the left nor the center thought that socialism could come through gradual reform. They saw elections as primarily educational. Once enough people were convinced, they would elect a majority of socialists to office and socialism at once would be instituted. This is very similar to the current theory of the Socialist Labor Party. Their conception was unclear on the need for insurrection, smashing the state, new forms of workers’ democracy to replace the bourgeois state or the need for a revolutionary party. In spite of these weaknesses, they were not reformists in the current gradualist sense.

Unclear theory contributed to be sure, but electoralist practice is what turned the party reformist. (“Being determines consciousness,” after all.) The Socialist Party was from the start primarily a propaganda organization. Even its large number of workers were not organized in fractions to influence working-class action and union policy. Instead, left-wing SP members as individuals were industrial militants. But as a party, the SP only tried to win workers’ support for their candidates.

Since the party’s main organized activity was electioneering, the conservative logic of electoralism asserted itself. Progressivism was on the rise among middle-class voters. To win these votes, the center watered down socialism and formed a bloc with the right. Of course, the result was tragic. Most of the revolutionary workers were forced out of the party or left in disgust by 1912. There was a growing theoretical and practical split between industrial and political action which rein forced reformism on the one hand and syndicalism on the other. Revolutionary socialism was not regenerated as a clear movement until the communist parties were formed in 1919. Even then it took years to overcome the legacy of the original reformist/syndicalist split.1

The Peace & Freedom Party

More recently, the Independent Socialist Clubs (ISC), ancestors of one wing of the current Solidarity, helped form the Peace and Freedom Party in California in 1968. The main program was Black liberation and withdrawal from Vietnam. This program was symbolized for the ISC by its proposal of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Benjamin Spock, the peace activist, for president and vice president. This would have been a liberal and not a socialist ticket. The final ticket was headed by the, at that time, radical Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver.

The ISC spent most of its energy from Fall 1967 to Fall 1968 building the Peace and Freedom Party and on its own reregistered 67,000 voters into the Peace and Freedom Party to get it on the 1968 ballot. This was a large accomplishment for a small group.

The strategy was to radicalize large numbers of anti-war activists and Blacks, i.e. move them one step to the left, out of the Democratic Party. So a revolutionary tendency buried its politics in a broader radical campaign. The result was a failure. Eugene McCarthy, the Democratic “peace” candidate, stole PFP’s thunder so the thousands of PFP registrants were radicalized, if at all, only temporarily.

The Sanders Campaign

The same problems can be seen today in socialist support for the Sanders campaign. Sanders calls himself a socialist but ran for governor in 1986 as an independent on a non-socialist program. Though many of his election planks were good, even his independence from the Democrats is questionable. His campaign manager was on the Democratic National Committee; he was endorsed by the national Rainbow Coalition and he sup ported Mondale in 1984. His administration has been decidedly nonsocialist. His emphasis has been on city government efficiency: “better” management practices. The most divisive issue of his administration has been the Lakeshore development on which he was supported by big business and opposed by the majority of his working-class supporters. (The development called for expansion of a hotel and condominiums in the $175,000 range.)

Of course some “socialists” opposed Sanders’ campaign as being too radical. Members of DSA (Democratic Socialists of America) faulted Sanders for running outside the Democratic Party. They feared his campaign might take votes away from the Democrats and result in the election of a Republican.

However, both Sanders and his DSA opponents agreed on one thing: the goal of elections is to win, not raise issues, educate and organize people for action to win changes or overthrow the system. As such, the conservative logic of electoralism dominated both approaches. For Sanders, winning meant dropping an explicitly socialist program. For DSA it meant dropping any independent candidacies at all. DSA’s position shows once again the conservatizing effects of working within the Democrats.

Although DSA was wrong to oppose Sanders from the right, there are severe problems with socialists joining the campaigns of nonsocialist candidates. It puts us in the position of defending nonsocialist solutions to society’s ills, even if the purpose is to win people away from the Democratic Party.

As we saw even “socialist” electoralism led to reformism in the early SP. This is so much more the case for support of a non-socialist reformer such as Sanders.

The reformist logic of electoralism shows clearly in Finkel/Feeley’s article in ATC when they say “What should matter for the left are not the fine points of whether Bernie Sanders has been 100% correct” but the fact that he is not a Democrat and so will make future breaks with the Democrats easier. They go on to say that the revolutionary left “must simultaneously carry out elective responsibilities and work to build counterinstitutions of working-class power.” So according to them, we should administer the state and smash it! In reality, it would be suicidal for revolutionaries to get elected to positions from which we must ad minister austerity on the working class. It would severely disorient any workers’ movement that we had an influence on and therefore make it harder for workers to organize a fight against austerity.

A left that attempted to administer capitalism and organize against it would find it impossible and would become schizophrenic and hypocritical. It would discredit the name of socialism for a long time to come.

Engels had an apt warning for anyone who would be tempted to follow Finkel/ Feeley’s approach and attempt to be a socialist in charge of a still capitalist state:

“The worst thing that can befall a leader of an extreme party is to be compelled to take over a government in an epoch when the movement is not yet ripe for the domination of the class which he represents … he necessarily finds himself in a dilemma … he is compelled to defend the interests of an alien class and to feed his own class with phrases and promises, with the assertion that the interests of the alien class are their own interests. Whoever puts himself in this awkward position is irrevocably lost. … Whoever can still look forward to official positions … is either foolish be yond measure, or at best pays only lip service to the extreme revolutionary party.(2)

Besides being wrong in theory as Engels shows, their strategy is unrealistic. The left simply does not have the forces to “carry out electoral responsibilities and “build counterinstitutions.” Our first task is now to grow on the basis of solid politics.

The other article by Brenner et, al. does not go to this extreme but also shows the danger of an electoralist orientation. Their article stresses over and over the need to strengthen mass movements as a supplement to IPA. They recognize that ‘1t is these struggles that will create the conditions for amassing the power to con- front capital.”

However, they fail to sufficiently appreciate the pitfalls of electoralism. They call for a “movement that both ran candidates and organized people to act on their own behalf.” The problem with this is that real struggle and electioneering tend to contradict each other.

To concentrate on electing someone to office is always to some degree to rely on them rather than the mass struggle. Reliance on the Democratic Party of course defuses movements but so does reliance on elections in general. The movement moderates its actions and ideas to the extent that its members believe that winning elections is important. Movements are far less able to resist the lures of winning elections than hard left parties are. The Greens in Germany with their recent battles between the “Realos” who want to block with the Social Democrats and the “Fundis” who want to stick to Green principles is a good example of this. So to call for IPA by movements is not to strengthen and politicize them but to reinforce electoralism and thus weaken them. We need a conception of politics that doesn’t center on elections.

Brenner et al. apologize for Sanders’ inability to enact reforms by saying that he is caught in the capitalist system. This is really the whole point. His dilemma shows that the role of socialists should be to oppose an electoralist strategy for the left. We should mobilize against even reluctant enforcers of capitalist policies not defend them as socialist or well-meaning.

Although Brenner et al. say, “It is of particular importance to strengthen the explicitly revolutionary pole within the left … ,” their strategy does not accomplish this. Concentrating on building the campaign of a reform “socialist” (if that!) is no way to build an explicitly revolutionary left. Instead of concentrating on building such a pole, their organization, Solidarity, raised money and offered almost uncritical support for a nonsocialist and certainly non-revolutionary candidate. The logic of their argument would lead them to do this again and again.

Independent Political Action

IPA tries to shatter the illusion that there are significant differences to the capitalist parties, which is good. However, what it tries to replace the illusion with is also an illusion: that elections and not the relation of class forces is the key to winning reforms. To move people to the left of the Democratic Party, it freezes people in that one leftward step by urging them to break with the Democrats because independent candidates will be better at winning reforms. It implies that the problem is the Democrats in particular rather than capitalism in general. It thus reconfirms support for the bourgeois electoral system. It assumes that everyone supports that system and hence can only be moved one step to the left (for now) to a more critical position within it.

Yet this is no longer true. In this country, close to half the people who vote don’t bother. The goal for leftists in relation to those people should not be to convince them that bourgeois make a difference (which is what Sanders and Jesse Jackson are trying to do). Instead it should be to convince them that a revolutionary alternative is possible.

But IPA advocates may ask “What about those who do support the Democrats?” It will be very difficult to break them from the Democratic Party without also breaking them from electoralism. Right now and for the foreseeable future the Democrats will be the most “practical” alternative for those who want to get people elected to office. The best way to convince people to break with the Democrats is to convince them that the electoral road to reform is not as effective as mass action. Proposing IPA is counterproductive to this goal as it too reinforces electoralism.

One failing of IPA is that it has an overly organizational, rather than political, approach. It is so focused on the need to break in formal terms with Democrats that it downplays the politics of that break. If, for example, the Rainbow Coalition became its own party and ran Jackson for President would its politics be very different than they are now? Probably not. Is its slightly more liberal capitalist program something that socialists should support if only Jackson were no longer a Democrat?

The logic of IPA suggests that socialists should support a “Rainbow Party.” Not all advocates of IPA may hold this position but the ISC’s earlier advocacy of a King/Spock ticket suggests that IPA could easily lead in this direction. Socialist support for liberals under any party name would be disastrous for the attempt to build a revolutionary tendency but IPA could lead to that disaster.

A Revolutionary Strategy for Today

If the strategy of IPA is not the best way to build a revolutionary current, what is? First of all in actual struggles such as strikes and actions against U.S. intervention, we should do three things: 1) support them, 2) offer a strategy for making the struggle more effective, based on our socialist analysis, and perhaps most importantly given the size of the left and the low level of struggle today, 3) do revolutionary propaganda with the aim of building a revolutionary current and organization.

Participation in actual struggles is much more worthwhile than electioneering. These struggles can win, at least to a degree, and build workers’ confidence, thus opening them to further struggle and political transition to the left. Victories by “socialist” candidates on the other hand teach one of two lessons: “socialists sell out” or “they can do it for us.”

The first lesson is good only if revolutionaries have warned that this will happen and explained the necessity of a non-electoral strategy. If we haven’t done this, the lesson “socialists sell out” will only cripple support for socialism in general. This is why it is absolutely essential to call for a different strategy from the beginning. Building illusions to later shatter them is dishonest and ineffective.

Revolutionaries & Elections

Does this mean that revolutionaries should ignore elections? No. The traditional position of revolutionaries toward social-democratic parties based in the labor movement has been critical support at election time. The purpose of this support has been exposing the inadequacies of reformists in office and therefore winning people away from a reformist strategy. So it has been key for revolutionaries to explain that a reformist strategy will not bring socialism or even significant to explain that a reformist strategy will not bring socialism or even significant reform by itself. The position has been “Vote Labor with no illusions.” Given Sanders’ lack of organic connection to the labor movement and his lack of a nominal socialist program, it is not clear that even this level of support would have been appropriate.

Should we then have ignored the Sanders’ campaign? No, but we should not have touted it as a great step forward for the left either. Instead of raising money and support for Sanders and future candidates like him we should concentrate on building a revolutionary current. If we urge a vote for Sanders, etc., it should be as revolutionaries treat reformists, “with no illusions” and with a clear explanation that we oppose Sanders whenever he inevitably attacks workers’ interests.

“With no illusions” means: “We don’t believe that the election of Sanders will make a difference to the lives of workers. Instead, we feel that workers need to organize independently to win any reforms that are possible now and in the long run need to replace the current system through a revolution. However since Sanders claims to be a socialist and opposed to the capitalist parties we say ‘If you vote, vote Sanders to prove in practice the failure of a reformist strategy to workers who are not yet convinced. But the elections are just a sidelight to the real work of workers’ self-organization.’”

If socialists call for a critical vote for labor parties shouldn’t we call for a labor party (one form of IPA)? If a mass workers’ movement for a labor party develops of course revolutionaries should participate in it, trying to influence it in a socialist direction, explaining the dangers of reformism, etc. However, participating in a real workers’ movement for a labor party is entirely different from calling for such a party before such a movement exists. To call for a labor party today means in reality to call for a social-democratic party since this is what all presently existing labor parties are, and have been, for a long time.

If we instead want a revolutionary party we should be clear and call for that. To call for a labor party with a socialist program or a labor party that would really be revolutionary is confusing and at best tries to sneak revolutionary politics in the back door. This is doubly true for the vaguer concept of IPA, which seems to be anything left of the Democrats.

Calling for IPA or even a labor party today is to focus on building politics that are not our own for a whole period of time. It is not just a tactical shift to take advantage of a real shift in activity and consciousness of workers. It is instead a strategy that substitutes non-revolutionary for revolutionary politics as the main focus of socialists for a whole period of time.

Notes

- The American Socialist Movement: 1897-1912, Ira Kipnis, Monthly Review Press,

back to text - The German Revolution Frederich Engels, University of Chicago Press, 1967, 103-104.

back to text

1972.

May-June 1987, ATC 9