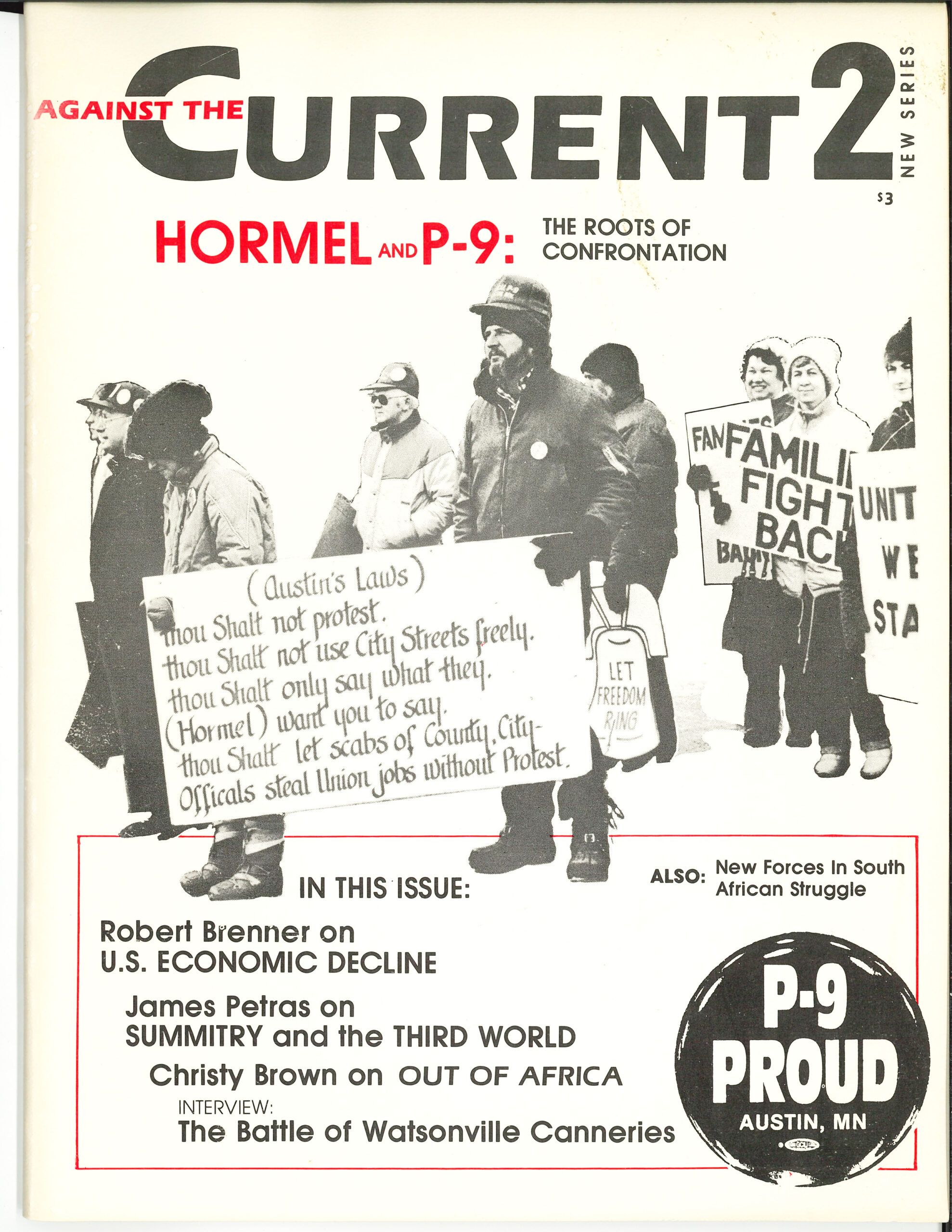

Against the Current, No. 2, March/April 1986

-

A Letter from the Editors

— The Editors -

The Deep Roots of U.S. Economic Decline

— Robert Brenner -

Summit Politics & the Third World

— James Petras -

COSATU: New Trend Emerges in South Africa Freedom Struggle

— Sandy Boyer & Dianne Feeley - COSATU Women's Resolution

-

Out of Africa: Isak Dinesen's Colonial Pastoral

— Christy Brown -

Random Shots: The Little Sect that Time Forgot

— R.F. Kampfer -

Letter re Theories

— Edward Joahn - Labor's War at Home

-

Teachers, Parents Win in Oakland

— Laurie Goldsmith -

Columbia University: Birth of a Union

— Lynn Geron -

The Long Battle of Watsonville

— Frank Bardacke -

Behind the Hormel Strike: Fifty Years of P-9

— Roger Horowitz - A Striking Family's Story

-

Austin Rally

— Roger Horowitz

James Petras

THE LINE OF antagonism between the U.S. and the USSR does not run through Berlin, Warsaw, and Prague but through the countryside of Guatemala, El Salvador, Angola, and Cambodia; and through the cities of South Africa, Brazil, and the Philippines.

The New Cold War did not originate in the failure of European detente but rather in the oil fields and bazaars of Iran and the jungles and towns of Nicaragua: in the mass popular insurrections that drove home to policy makers in Washington the fact that neither U.S. investments and loans nor hegemonic control and regional domination could be sustained without a massive, active military machine supported by a mobilized public and subservient Congress.

Only by evoking the specter of Soviet expansion could Washington hope to convince the American public to support the new interventionism and the escalating arms race. Soviet intervention in Afghanistan was inflated into a world-historic event-then linked and amalgamated with Third World revolutions everywhere.

With the Third World as target and the Soviet Union as the bogeyman needed for plausibility, the new spiral in the arms race still required some endorsement from other quarters to gain acceptance. This it received from most of the West European regimes, particularly the French Social Democrats and Thatcher, that unholy alliance of hypocritical and candid reaction. Meanwhile, Reagan pro vided himself a cover for further escalation with a masterful display of talking peace while preparing for war at the Geneva summit and by promoting a series of “demonstration elections” in Third World dictatorial regimes, designed to prove that his goal is merely democracy.

The Road to the Summit: The Decline & Resurrection of U.S. Militarism

The New Cold War has its origins in the decline of U.S. military power, as a direct consequence of the U.S. defeat in Vietnam. U.S. military decline occurred at the precise moment when U.S. financial and service activity was expanding rapidly throughout the Third World. While the imperial state apparatus was disarticulated-through massive demoralization of a conscript army and widespread public opposition to military spending and intervention-the principal U.S. banks were becoming increasingly dependent on overseas earnings to sustain their operations. Financial capital invaded the Third World unaccompanied by the protection of the imperial state; relations of exploitation and conflict were intensified without the necessary defensive shield.

U.S. policy makers responded to this crisis in its world power position and the resulting vulnerability of capital by introducing two new strategic approaches: detente with the USSR and the buildup of regional power centers in the Third World. Through detente Washington attempted to enlist Soviet support to contain revolution in exchange for arms agreements. This was the essence of Kissinger’s policy of “global linkages.”

Through regional power centers Washington sought to strengthen the role of specific countries (Iran, Brazil, Israel, and South Africa) as “local policemen.” The U.S. thus aimed to exercise control indirectly through the intervention of regional military powers, and thus to compensate for its declining capacity to intervene directly.

Neither strategy succeeded in blocking the revolutionary upsurge in the aftermath of Vietnam. The basic flaw in Kissinger’s conception of detente was the notion that superpower agreements can contain Third World revolution. The Soviets could not control what was not the pro-Soviet parties were irrelevant to the revolution. Only in Afghanistan did a pro-Soviet party take power, and then it appeared without prior Soviet approval (though the Soviets later came to the regime’s rescue).

The regional power strategy also failed. The Shah’s ability to follow through on his overseas commitments and back up his grandiose military posturing was destroyed by popular revolution. The Brazilian regime’s inability to cope with the severe economic crisis led to mass discontent, the isolation of the military, and its retreat from regional hegemonic aspirations. Israel’s lack of political leverage in the Middle East led to destructive military actions that eroded rather than consolidated U.S. influence. South Africa’s defeat in Angola, the rising mass movements within the country, and worldwide solidarity undermined Washington’s capacity to rely on the racist regime to safeguard its interests in Southern Africa.

As a consequence of the failure of detente and regional power strategies, Washington began, under Carter and then Reagan, to reestablish the imperial state in order to project power unilaterally. Reasserting a global military presence was a paramount concern in light of the revolutionary consequences resulting from a disarticulated state.

Revolutions in Nicaragua, Iran, Angola, and Grenada, along with the displacement of U.S. clients in Ethiopia and Afghanistan, were viewed with consternation by bankers, generals, and politicians. A publicly supported, well financed, and mobile imperial state was necessary to safeguard the worldwide financial empire, to reestablish hegemony in contested areas, to enforce compliance among debtors, to extend a powerful presence into all regions of potential conflict. For Washington, the New Cold War, with its unilateral military escalation, was the only alternative to the failure of detente and regional power strategies.

If the New Cold War thus began with the failure of detente and sub imperialism and with the initial series of revolutions of the mid to late 1970s, the massive escalation of U.S. military programs coincides with the extension of those revolutions to adjoining regions. A social revolution not just in Angola and Mozambique, but also in South Africa, or the extension of antiimperialist movements from Iran to the Gulf States, or the replication of a Nicaraguan-type revolution elsewhere in Central America — any of these would be major strategic defeats for Washington. Washington has therefore developed a strategy aimed not only at containing the current revolutionary wave, but also at rolling back the revolutionary regimes of the 1970s.

To accomplish these twin goals the Reagan Administration has naturally targeted the Soviet Union as one of the primary economic and military supporters of the existing revolutionary regimes and as a propaganda foil to legitimate intervention in revolutionary conflicts. B threatening the Soviets with superior nuclear arms Washington is attempting to pressure the Soviets into giving Washington a free hand in its attack on revolutionary governments.

The goal of the Reagan Administration’s conventional military aid programs to the various and sundry “contra” forces is to establish U.S.-controlled client states. Nuclear weapons at the international level are perceived to be useful for keeping third parties out of the way to permit unrestricted military intervention with conventional arms at the regional (Third World) level.

The new strategic approach is thus premised on a rejection of the notion of U. S.-Soviet parity (integral t detente). The “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) is merely the most visible and costly aspect of a sustained and larger military program that has reverse every military constraint agreed to over the past twenty five years. SDI is designed to protect U.S. missiles in order to facilitate a first-strike capability, destabilizing the relative parity that now exists. By achieving nuclear superiority Washington hopes to intimidate the USSR in to accepting U.S. primacy in the world.

Meanwhile, chemical weapons are being manufacture once again (banned in 1969). Police training funds have received bipartisan support (banned since 1974 because of U.S. involvement with torturers). Military aid is promised to many of the pariah-assassins of the 1970s: Thus the Guatemalan military; South Africa’s surrogate, UNITA in Angola; the Somocista-led Contras in Nicaragua are all soon to receive massive increases in military aid.

The new projection of U.S. military power reflects the relative decline of U.S. production, trade, and economic control. Military force is being used to compensate for economic weakness. Washington’s military escalation program is thus partly aimed at coping with the increasingly unstable financial structures of U.S.-based multinational banks. The growing incapacity of major Third World debtors even to meet their interest payments, and the fifth consecutive year in which Latin America as whole has had a zero or negative growth rate, has create a volatile political situation.

Washington’s nuclear and conventional arms buildup is designed to prevent Third World regimes from choosing political-economic options that break with the U.S. and its banks. The importance of these financial linkages is greatly heightened by the decreasing trade and industrial position of the U.S. Without the earnings from Third World interest payments, the trade deficit would reach unmanageable proportions.

Contradictions of the Buildup

Nevertheless, the strategy of projecting overpowering military strength at the global level has already had contradictory consequences. The high level of military spending has both increased the U.S. trade deficit (reflecting the declining competitiveness of U.S. industry), and increased U.S. dependence on investment from other countries in the U.S., (this reached one trillion dollars in 1985). In 1984 “the net capital contribution of foreign investors (the difference between foreign investment in the United States and American investment overseas) reached 95 billion … and may top 130” in 1985.” (New York Times, December 29, 1985, p. 18).

The massive budget deficit Reagan has been running to finance military expansion is paid for by mortgaging future government revenues to pay back the loans the government is floating now. The promise of relatively high interest backed by the U.S. government has sucked up foreign capital like a sponge absorbs water, drawing it away from potentially productive investment in other parts of the world.

Paul Volker of the Federal Reserve has warned that “it is clearly not healthy for the largest and richest country in the world-in its own interests or that of others — to use up so much of the world’s savings to finance a budget deficit.” (New York Times, December 29, 1985, p. 18). The bulk of the foreign capital in the United States (84 percent) is in nonproductive activities such as bank deposits and securities (mostly government banks). The result is that the interest payments and profits going to foreign investors are exceeding the creation of new profitgenerating activity.

A further negative consequence of the military-sparked deficit will be seen in the next U.S. recession. Since most foreign capital is in the form of stocks and government securities rather than in actual plants, it is highly mobile and very responsive to fluctuations in the value of corporate stock or U.S. interest rates. Any new recession will be substantially deepened by the resulting outflow of capital.

The growing economic costs of the arms buildup, if nothing else, have begun to generate opposition to further militarization in the U.S. Meanwhile, military escalation continues to be used to recover lost influence, even in Europe. The emplacement of nuclear missiles in Europe and the development of new space weaponry are designed to decrease Europe’s autonomy and thus its capacity for either economic or political initiatives. This has not gone unnoticed by the Europeans.

The U.S. global military strategy has engendered significant opposition in both Europe and the U.S. Washington’s decision to go to the summit was essentially a propaganda gesture to neutralize the opposition by coopting its minimalist demands (the vacuous call for “negotiations”).

The Geneva Summit: Talking Peace & Preparing for War

The summit and its immediate aftermath clearly demonstrated Washington’s intention to use the “peace process” to escalate the arms race. As Hedrick Smith noted,

“At the White House, the ebullient reaction from both Congress and the public to the President’s performance in Geneva is being read as evidence that the summit has bought Mr. Reagan renewed public patience for his approach to Moscow and another year or two of funding for his space defense program without serious challenge.” (New York Times Magazine, December 8, 1985, pp. 80-81)

The day after the celebrated Reagan-Gorbachev summit meeting, the director of the Strategic Defense Initiative program, Lieutenant General Abrahamson, said that after Geneva he expected to move “much more quickly and effectively” with the design of a space-based defense against missiles (New York Times, November 21, 1985, p. 1). Two days after the summit the Federal Government awarded a $300 million contract to Hanford National Laboratory in Richland, Washington, to develop a compact space-based nuclear reactor to power the weapons and radar in Reagan’s SDI program.

Reagan’s refusal to reaffirm the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty of 1972 and his refusal to reciprocate the Soviet unilateral moratorium on nuclear testing with on-site verification confirms the view of the summit as a step backward from the limited progress of the 1970s. Reagan’s intransigence and Gorbachev’s failure to influence him have laid the groundwork for a new arms race. Reagan’s ability to turn the summit meeting into a huge public relations coup allowed him to further accelerate the arms race.

But the most provocative aspect of Reagan’s summit diplomacy, however, concerned the question of “regional conflicts.” Reagan’s policy has aimed not only at increasing intervention against revolutionary regimes in Angola and Nicaragua, but also at weakening Soviet military and economic support for these countries. The day after the summit ended, Reagan publicly stated that his administration favored covert aid to the South Africanbacked UNITA forces in order to overthrow the leftist government of Angola. Reagan claimed that covert aid “would have much more chance of success right now than aid allocated by Congress” (New York Times, November 23, 1985, p. 1).

On the same day, the United Nations General Assembly began debate on the situation in Central America. In response to Nicaragua’s exposure of U.S. backing of armed aggression through a mercenary army, U.S. representative and former CIA leader Vernon Walters defended Washington’s support for armed terrorists, describing them as the “democratic resistance” (New York Times, November 23, 1985, p. 2).

In the West the summit created a false aura of progress through understanding. But while, in Europe, Mitterrand, Thatcher, and Kohl congratulated Reagan for his peaceful gestures, in Angola, Nicaragua, and El Salvador, the people were preparing for an escalation of war and destruction.

In effect, Reagan has renewed Henry Kissinger’s old “linkage” policy. As Reagan himself put it, “If there is a real interest [in arms control] on the Soviet side, there is a chance that talks can begin to make headway We will be watching very closely for any changes in Soviet activities in the Third World” (New York Times, November 24, 1985, p. 17).

Reagan’s reworking of linkage politics, it must be emphasized, is set in a new context. In the aftermath of Vietnam when Nixon and Kissinger devised the policy there were strong restraints on U.S. military expansion. Today there are no such restraints, so this kind of blackmail bargaining becomes all the more dangerous.

Coopting the liberals Behind Third World Counterrevolution

To disarm opposition to its reckless policy and thus to increase its effectiveness, the Administration has adopted a strategy aimed at pushing the liberals and Social Democrats into active opposition to the Third World movements and governments Washington wishes to destroy. This is the strategy of “demonstration elections.” Faced with rising social movements against client military states and unable to secure massive U.S. public and Congressional support, the Reagan Administration organizes elections with a restricted and approved list of candidates. In other cases Washington engages in presumptive coups through its client generals against the incumbent dictatorships to preserve the state apparatus, divide the civilian opposition and secure U.S. Congressional aid to revitalize the repression of the social movements.

For example, working through the military Washington deposed Duvalier in Haiti, leaving behind a government of pro-U.S. supporters from the Duvalier regime. In the Philippines, it imposed a number of key Marcos officials on the Aquino coalition to contain the new regime’s reforming proclivities, after “demonstration election” strategy became the basis for independent mass movement that escaped its control.

In promoting “demonstration elections,” the Reagan Administration strategy is to secure liberal Congressional support for its military campaign against revolutionary regimes. Hence, in the aftermath of the ascent to power of the Aquino-Ramos coalition with Washington’s compliance, Secretary of State Schultz argued for $10 million aid for contra terrorism in Nicaragua.

The Administration’s two-pronged strategy of terror and elections is thus designed to pressure European an liberals and Social Democrats to demand that the Sandinistas not purchase arms from the Soviet Union, that they integrate the terrorists into the government … that they do anything, in short, except defend themselves an’ determine their own political and economic system.

The common platform proposed to the liberals, with considerable success, by the Administration is support to free elections and opposition to terrorism. So we have U.S. representative to the United Nations Vernon Walter speaking solemnly there against “terrorism” everywhere — while in the American mass media he defend right-wing terrorists in Central America, Kampuchea and! Angola. This is the same Vernon Walters who as chief CIA operative contributed to the installation of the1 Brazilian state terrorist regime in 1964, a man who was and remains a confidante of death squad leaders and military intelligence officials from Chile to El Salvador.

Washington hopes to secure Soviet compliance with bid for hegemony in the “trouble spots” by offering several inducements, including increased trade, future summit meetings, and vague promises of possible understandings. But despite Gorbachev’s meetings with 400 U.S. business leaders shortly after the 1985 summit and the preparations for a visit to Washington in 1986, the Reagan Administration is adopting measures and policies which portend an increasingly confrontationist outcome.

Having secured Congressional assent for a bigger military budget, including the SDI, and having committed itself to a worldwide strategy of armed support for surrogate forces against revolutionary regimes, many of which receive some support from the Soviet Union, the U.S. government is very likely to precipitate ugly conflicts and a return to the worst period of the Cold War is fast approaching.

Electoral Processes & the Militarization of the Third World

The electoral processes that have so strikingly surfaced in several long-time dictatorships of the Third World are intimately tied to increased U.S. military involvement in these countries, a development little discussed by liberal commentators. The elections are orchestrated from Washington to neutralize domestic and overseas opposition to the military — and to open the spigot for massive flows of funds subsequent to the elections.

The elections in 1985 in Guatemala, for example, were accompanied by a headline in the Christian Science Monitor that read: “New Civilian Rule Prompts Call for Resumption of US Military Aid” (December 10, 1985). In the text of the article, liberal Democratic Senator Claiborne Pell reportedly expressed “his view that U.S. military aid should be restored as Cerezo took office.” New civilian ruler Cerezo, however, had been compelled by the army general staff, in order to be allowed to run at all, to pledge not to investigate or reform the military, which has been responsible for the murder of tens of thousands of peasants, Indians, and workers.

Guatemala, where military command is synonymous with death-squad activity, will now be inundated with U.S. funds, voted in a truly bipartisan manner. The links with the U.S. military will be deepened and the basis will be laid to integrate the Guatemalan military into the U.S.’s strategy for encircling and confronting Nicaragua. If Cerezo balks at Washington’s plans, the aid will dry up. And in time he will be ousted, with a lament in the liberal press that he lacked some indefinable quality of leadership.

Reagan was also a promoter of the elections in the Philippines. Up to a year ago, Washington was a staunch supporter of the Marcos authoritarian dictatorship. The sudden turn to elections was the result of the massive growth in support for the social revolutionary New People’s Army, and Washington’s fear that Marcos did not have the political and military capacity to defeat it. The calculation was that elections would either legitimate Marcos, or, as second-best, establish a new government that would capture the mantle of being anti-Marcos, thus undermining the New People’s Army, while maintaining the essentials of the client relationship with the U.S.

The Aquino campaign and Marcos’ “rape of democracy,” as the London Times called it, reveal the purely formal opposition of the Reaganites to dictatorial rule. In this, from Washington’s viewpoint, worst possible scenario, the election was shown to be a fake before the ballots were counted. Reagan discredited himself in front of the world by appealing to Aquino to accept the rigged balloting. He was then forced to dump Marcos anyway when the outrage of the Philippine people ran so deep that even the military high command and the diplomatic corps jumped ship.

Washington did not lose a minute in changing sides, praising Aquino alternately as a champion of democracy and as a pragmatist who had retained enough of the old dictator’s officers in her cabinet to become an effective force for crushing the popular insurgency in the country — for which purpose millions of American dollars were immediately pledged.

Reagan’s endorsement of Marcos’ victory in the first days after the Philippine election indicated that the Administration was more interested in using the election to secure Congressional financing for counterinsurgency activity than in the violent and fraudulent means by which the election was carried out.

The mass mobilization and threat of imminent civil war, involving over 70 percent of the population against the U.S.-backed Marcos regime, caused Reagan to shift toward sacrificing Marcos in order to preserve the military-police apparatus and the economic structure. The Reagan version of power-sharing envisions the subordination of the Aquino liberals to the Marcos apparatus; but the Aquino coalition came to power on the wave of mass demonstrations, and the rigid and narrow constraints imposed by the Reagan-Marcos apparatus come into conflict with the mass movement’s most elementary demands: freedom for political prisoners, cleansing the Supreme Court of Marcos loyalists, negotiations with the leftist National Democratic Front, etc.

If Aquino pursues a program of democratic change, and attempts to carry out some of the significant reforms proposed by the left-led social movement, the U.S. Marcos apparatus will escalate its pressure, and the forced marriage between Ramos and Aquino will come apart.

Washington, in promoting a demonstration election to facilitate massive military aid to Marcos, underestimated the scope and depth of popular organization and opposition. The result of the electoral mobilization has been to heighten the level of struggle. The overthrow of Marcos was the first, not the last chapter of the story.

Prospects for the Third World

The crises in Third World-U .S. relations will likely result in growing estrangement if not open ruptures, whether they take the form of debt moratoria or social upheavals. The extent of the decline in economic ties will depend in large part on whether Third World regimes are able-or willing to risk-finding alternate sources of trade and advanced technology through new economic linkages to the USSR, Western Europe, or Japan. Such moves, though nominally the right of independent nations to decide on their own without outside pressure, will in practice be targeted for destabilization programs designed by Washington or outright military intervention in one form or another.

Several new historical developments are working against Washington’s efforts to restabilize its hegemony. First and foremost is the radicalization of the South African revolution. This radicalization is expressed in several aspects of the struggle: the increasing presence of the industrial working class in the confrontations with the regime, the growing anticapitalist content of the slogans supported by the young militants, the expanding capacity of Blacks to confront the state violence of the white regime with revolutionary violence.

A revolutionary South Africa, as the most advanced industrial and military power on the African continent, would be in a position to sustain and support the revival and deepening of the African revolution throughout the Sub-Saharan region. The Reagan Administration, which has been working in tandem with South Africa to reverse the revolutionary developments in Angola, Namibia, and the rest of Southern Africa, is thus unable to dissociate itself from the current regime. Washington’s strategy of “rollback” in Southern Africa is being challenged by the ascending revolutionary struggle in Black South Africa and continuing Soviet and Cuban support for the Angolan revolution.

In Central America the massive influx of U.S. military and economic aid, advisers, and CIA-directed mercenary forces has increased the level of conflict and killings-without establishing any territorial bases in Nicaragua or inflicting any strategic defeats on the guerrillas in El Salvador. In the meantime, the revival of the mass social movements in El Salvador and Guatemala – – their open rupture with Duarte and pressure on the new Guatemalan president, Cerezo-suggest that whatever marginal military gains Reagan made in the countryside are being counterbalanced by losses in the cities.

In the rest of Latin America the deepening of the debt crisis is evident in the precipitous decline of military regimes-originally Washington’s prime allies in the region. While the elected regimes manifest a tendency to uphold their debt obligations, there are signs everywhere that there are political limits to further encroachments on living standards and development imperatives. Peru has placed a 10 percent cap (10 percent of export earnings) on its debt payments; Mexico is several months behind in its interest payments; and popular pressure on the Sarney regime in Brazil is evident in the growing polarization between the right (led by Janio Quadros) and the left (Brizola and the Workers Party).

The newly elected conservative civilian regimes in Latin America and elsewhere are transitory phenomena. Unable to resolve their internal problems as long as they comply with their debt obligations to the bankers, they are creating conditions for a new radicalism which will challenge Reagan’s efforts to reassert hegemony in this hemisphere.

Even Washington’s relations with China are gradually shifting. China has clearly put distance between its policies and Washington in a number of areas: China is improving relations with the USSR; developing ties with revolutionary regimes — including Nicaragua-on terms critical of Washington’s pretensions; and insisting on greater access to U.S. markets in exchange for continuing the expansion of trade.

Post Summit Reflections

Washington’s pressure on the Soviets to escalate their arms program is the most salient feature of the postsummit period. The summit was a prelude to new confrontations: in response to a renewed Soviet offer to sign a moratorium on nuclear testing, Washington launched a front-page attack charging the Soviets with violating previous agreements. These attacks were largely fabrications, as several U.S. arms experts and former armscontrol officials have pointed out. Even the State Department confirms this. The New York Times reports: ‘The Soviet Union has complied with the vast majority of important arms control provisions according to private Congressional testimony by ranking State Department official” (January 10, 1986, p. 3A).

The meaning of the attack on the Soviets was that Washington is not interested in discussing any proposal for arms control at this time. So long as no arms control plan will be considered in Washington it seems likely that Gorbachev will also turn to a new round of weapons development, such as sea-based cruise missiles and Blackjack bombers capable of penetrating beneath any envisaged American space shield.

It was a major weakness of the Western peace movement that it failed correctly to assess the implications of Reagan’s decision to break with the previous policy of nuclear parity, and therefore to see in Gorbachev’s moratorium proposal a practical possibility to avert a worsening of the nuclear arms situation. Hedrick Smith summarized Gorbachev’s offer as “wanting a halt to the development of space defenses; a moratorium on nuclear testing; a one year extension of the 1979 arms agreement to the end of 1986, or some compromise framework for arms control” (New York Times Magazine, December 8, 1985, p. 72).

These are clear and positive proposals. They have added weight because they come from one of the parties able to act in the situation. As such they should be endorsed by the peace movement in the West. The concept of “equal superpower responsibility” for the arms race, which dominates the Western peace movement, becomes a dogma when it fails to acknowledge the drastic new initiative in the arms race taken by one side, the Reagan escalation. The failure to recognize a distinction in the practical actions of both sides at this concrete moment in time leaves the peace movement unable to intervene in the real existing struggle, deepening the disorientation which has engulfed it since the failure to block the Cruise missile emplacements in Western Europe.

The peace movement should not lessen its criticism of internal Soviet institutions or of Moscow’s reactionary foreign policies, such as support for the Ethiopian military in Eritrea. But it must transcend the old boundaries of symmetrical responsibility for the arms race if it hopes to regain political credibility and initiative. That is, it must grasp the source of the present arms race, not in superpower competition in the abstract or as some property inherent in the arms themselves, but as a consequence above all of U.S. economic relations with the Third World. Understanding that, it should also be clear that an effective international force for peace can be built only by defeating the social-economic basis for war.

March-April 1986, ATC 2