Against the Current No. 238, September-October 2025

-

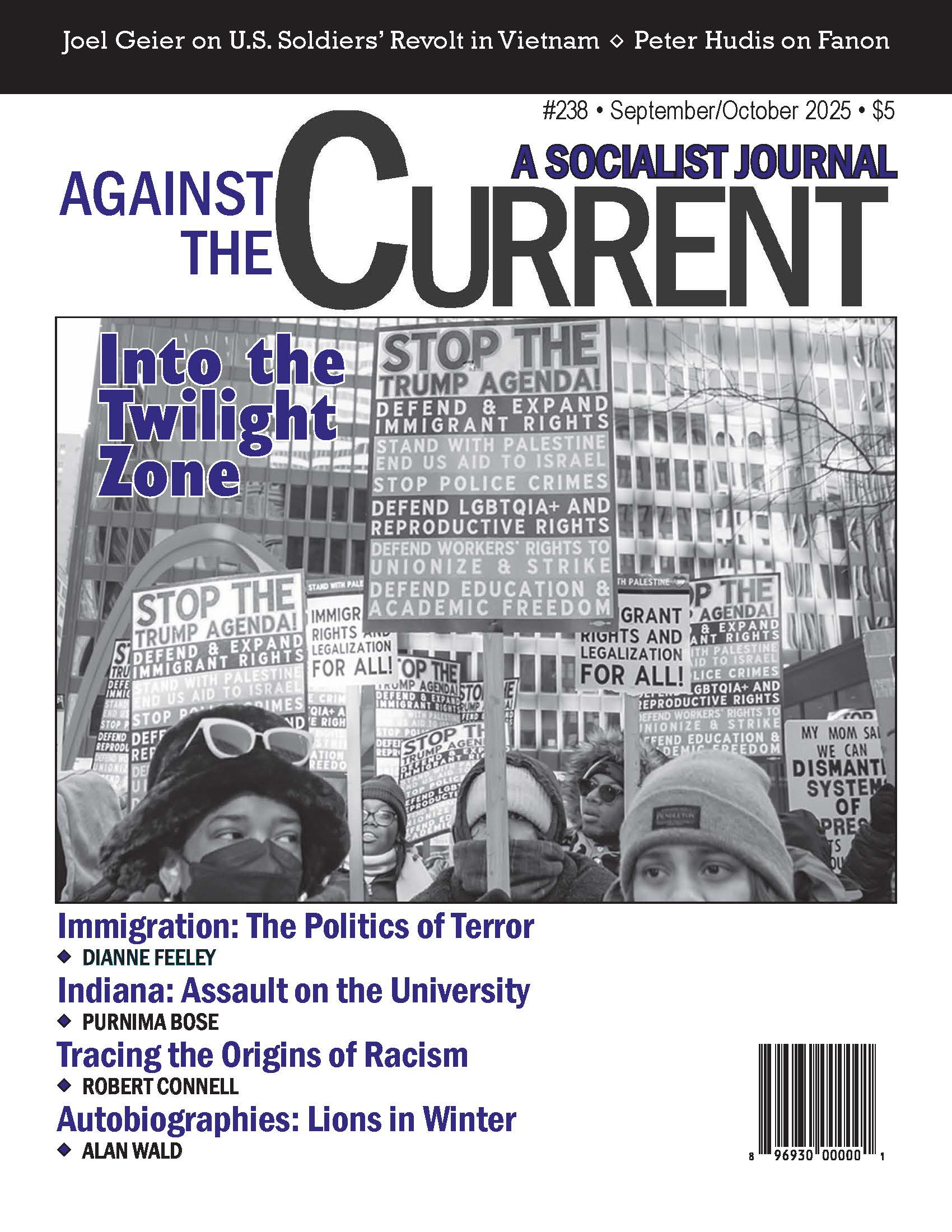

In Twilight-Zone USA

— The Editors -

Indiana's Assault on Public Education

— Purnima Bose -

Trump's Brutal Immigration Policies

— Dianne Feeley -

Team Trump's Immigration Protocols

— Dianne Feeley -

ICE Terror Unleashed in Los Angeles

— Suzi Weissman interviews Flor Melendrez -

From Welfare Toward A Socialist Future

— David Matthews -

Honoring Anti-Fascist Resistance

— Jason Dawsey -

What Future for the Middle East

— Valentine M. Moghadam -

Bloody Amputation: Trump’s “Peace” for Ukraine

— David Finkel - Vietnam

-

The Soldier's Revolt, Part I

— Joel Geier - Review Essays

-

Lions in Winter: Longtime Activist Lives on the Left

— Alan Wald -

Fascism, Jim Crow & the Roots of Racism: Tracing the Origins

— Robert Connell - Reviews

-

Republican and Revolutionary?

— David Worley -

Frantz Fanon in the Present Movement

— Peter Hudis -

The Power of Critical Teacher: About Palestine & Israel

— Jeff Edmundson -

Hearing the Congo Coup

— Frann Michel

Joel Geier

AGAINST THE CURRENT is marking the 50th anniversary of the end of the war in Vietnam, which concluded with the biggest defeat inflicted on U.S. imperialism. We are beginning by republishing Joel Geier’s retrospective on the near-collapse of the U.S. army in Vietnam, which appeared in the International Socialist Review, issue 9, Fall 1999. It appears in the Encyclopedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL), Joel Geier Archive, downloaded from the ISR Archive Website. Thanks to the author for reprint permission, and to Lisa Lyons for her cartoons from the period.

“Our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near-mutinous [c]onditions [exist] among American forces in Vietnam that have only been exceeded in this century by … the collapse of the Tsarist armies in 1916 and 1917.” —Armed Forces Journal, June 1971(1)

THE MOST NEGLECTED aspect of the Vietnam War is the soldiers’ revolt — the mass upheaval from below that unraveled the American army. It is a great reality check in an era when the U.S. touts itself as an invincible nation. For this reason, the soldiers’ revolt has been written out of official history. Yet it was a crucial part of the massive anti-war movement whose activity helped the Vietnamese people in their struggle to free Vietnam — described once by President Johnson as a “raggedy-ass little fourth-rate country” — from U.S. domination.

The legacy of the soldiers’ revolt and the U.S. defeat in Vietnam — despite more recent U.S. victories over Iraq and Serbia — casts a pall on the Pentagon. They still fear the political backlash that might come if U.S. ground forces sustain heavy casualties in a future war.

The army revolt was a class struggle that pitted working-class soldiers against officers who viewed them as expendable. The fashionable attempt to revise Vietnam War history, to airbrush its horrors, to create a climate supportive of future military interventions, cannot acknowledge that American soldiers violently opposed that war, or that American capitalism casually tolerated the massacre of working-class troops.

Liberal academics have added to the historical distortion by reducing the radicalism of the 1960s to middle-class concerns and activities, while ignoring working-class rebellion. But the militancy of the 1960s began with the Black working class as the motor force of the Black liberation struggle, and it reached its climax with the unity of white and Black working-class soldiers whose upsurge shook U.S. imperialism.

In Vietnam, the rebellion did not take the same form as the mass stateside GI antiwar movement, which consisted of protests, marches, demonstrations and underground newspapers. The aim of the soldiers was more modest, but also more subversive: survival, to “CYA” (cover your ass), to protect “the only body you have” by fighting the military’s attempt to continue the war. The survival conflict became a war within the war that ripped the armed forces apart. In 1965, the Green Machine was the best army the United States ever put into the field; a few years later, it was useless as a fighting force.

“Survival politics,” as it was then called, expressed itself through the destruction of the search-and-destroy strategy, through mutinies, through the killing of officers, and through fraternization and making peace from below with the National Liberation Front (NLF). It was highly effective in destroying everything that military hierarchy and discipline stand for. It was the proudest moment in the U.S. army’s history.

Like most of the revolutionary traditions of the American working class, the soldiers’ revolt has been hidden from history. The aim of this essay is to reclaim the record of that struggle.

A Working-Class Army

“The Vietnamese lack the ability to conduct a war by themselves or govern themselves.” —Vice President Richard M. Nixon, April 16, 1954(2)

From 1964 to 1973, from the Gulf of Tonkin resolution to the final withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam, 27 million men came of draft age. A majority of them were not drafted due to college, professional, medical or National Guard deferments. Only 40% were drafted and saw military service. A small minority, 2.5 million men (about 10% of those eligible for the draft), were sent to Vietnam.(3)

This small minority was almost entirely working-class or rural youth. Their average age was 19. Eighty-five percent of the troops were enlisted men; 15% were officers. The enlisted men were drawn from the 80% of the armed forces with a high school education or less. At this time, college education was universal in the middle class and making strong inroads in the better-off sections of the working class. Yet, in 1965 and 1966, college graduates were only two percent of the hundreds of thousands of draftees.(4)

In the elite colleges, the class discrepancy was even more glaring. The upper class did none of the fighting. Of the 1,200 Harvard graduates in 1970, only two went to Vietnam, while working-class high schools routinely sent 20%, 30% of their graduates and more to Vietnam.(5)

College students who were not made officers were usually assigned to non-combat support and service units. High school dropouts were three times more likely to be sent to combat units that did the fighting and took the casualties. Combat infantry soldiers, “the grunts,” were entirely working class. They included a disproportionate number of Black working-class troops. Blacks, who formed 12% of the troops, were often 25% or more of the combat units.(6)

When college deferments expired, joining the National Guard was a favorite way to get out of serving in Vietnam. During the war, 80% of the Guard’s members described themselves as joining to avoid the draft. You needed connections to get in — which was no problem for Dan Quayle, George W. Bush and other ruling-class draft evaders.

In 1968, the Guard had a waiting list of more than 100,000. It had triple the percentage of college graduates that the army did. Blacks made up less than 1.5% of the National Guard. In Mississippi, Blacks were 42% of the population, but only one Black man served in a Guard of more than 10,000.(7)

In 1965, the troops came from a working class that had moved in a conservative direction during the Cold War, due to the long postwar boom and McCarthyite repression. Yet in the five years before the war, the civil rights movement had shaped Black political views. The troops had more class and trade-union consciousness than exists today.

The stateside Movement for a Democratic Military, organized by former members of the Black Panther Party, had as the first points of its program, “We demand the right to collective bargaining,” and “We demand wages equal to the federal minimum wage.”(8)

When the Defense Department attempted to break a farm workers’ strike by increasing orders for scab lettuce, soldiers boycotted mess halls, picketed and plastered bases with stickers proclaiming “Lifers Eat Lettuce.”(9) When the army used troops to break the national postal wildcat strike in 1970, Vietnam GI called out, “To hell with breaking strikes, let’s break the government.”(10)

Shortly after the war began, radicalism started to get a hearing among young workers. As the Black liberation struggle moved northward from 1965 to 1968, 200 cities had ghetto uprisings — spreading revolutionary consciousness among young, working-class Blacks. In the factories, those same years saw a strong upturn in working-class militancy, with days lost to strikes and wildcats doubling.(11)

Left-wing ideas from the student movement were reaching working-class youth through the anti-war movement. In 1967 and 1968, many of the troops had been radicalized before their entry into the army. Still others were radicalized prior to being shipped to Vietnam by the GI anti-war movement on stateside bases. Radicalizing soldiers soon came up against the harsh reality that the officers viewed working-class troops as expendable.

The Middle-Class Officers Corps

“Let the military run the show.” —Senator Barry Goldwater(12)

The officer corps was drawn from the seven percent of troops who were college graduates, or the 13% who had one to three years of college. College was to officer as high school was to enlisted man. The officer corps was middle class in composition and managerial in outlook. Ruling-class military families were heavily represented in its higher ranks.(13)

In the Second World War, officers were seven percent of the armed forces, an amount normal for most armies. The officer corps used the postwar permanent arms economy, with its bloated arms budget, as its vehicle for self-expansion. By the time of the Vietnam War, the officer corps was 15% of the armed forces, which meant one officer for every six plus men.(14)

After the end of the Korean War in 1953, there was no opportunity for combat commands. As the old army song goes, “There’s no promotion/this side of the ocean.” In 1960, it took an excruciating 33 years to move from second lieutenant to colonel. Many of the “lifers,” professional officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs), welcomed the Vietnam War as the opportunity to reinvigorate their careers.

They were not disappointed. By 1970, the agonizing wait to move up the career ladder from second lieutenant to colonel had been reduced to 13 years.(15) Over 99% of second lieutenants became first lieutenants, 95% of first lieutenants were promoted to captain, 93% of qualified captains became majors, 77% of qualified majors became lieutenant colonels and half of the lieutenant colonels became colonels.(16)

The surest road to military advancement is a combat command. But there were too many active duty officers of high rank, which produced intense competition for combat commands. There were 2,500 lieutenant colonels jostling for command of only 100 to 130 battalions; 6,000 colonels, 2,000 of whom were in serious competition for 75 brigade commands; and 200 major generals competing for the 13 division commands in the army.(17)

General Westmoreland, commander of the armed forces in Vietnam, accommodated the officers by creating excessive support units and rapidly rotating combat command. In Vietnam, support and service units grew to an incredible 86% of military manpower. Only 14% of the troops were actually assigned to combat. Extravagant support services were the basis for the military bureaucracy.

The armed forces created “numerous logistical commands, each to be headed by a general or two who would have to have high-ranking staffs to aid each of them.” Thus it became possible for 64 army generals to serve simultaneously in Vietnam, with the requisite complement of colonels, majors etc.(18)

These superfluous support officers lived far removed from danger, lounging in rear base camps in luxurious conditions. A few miles away, combat soldiers were experiencing a night-marish hell. The contrast was too great to allow for confidence — in both the officers and the war — to survive unscathed.

Westmoreland’s solution to the competition for combat command poured gasoline on the fire. He ordered a one-year tour of duty for enlisted men in Vietnam, but only six months for officers. The combat troops hated the class discrimination that put them at twice the risk of their commanders. They grew contemptuous of the officers, whom they saw as raw and dangerously inexperienced in battle.

Even a majority of officers considered Westmoreland’s tour inequality as unethical. Yet they were forced to use short tours to prove themselves for promotion. They were put in situations in which their whole careers depended on what they could accomplish in a brief period, even if it meant taking shortcuts and risks at the expense of the safety of their men — a temptation many could not resist.

The outer limit of six-month commands was often shortened due to promotion, relief, injury or other reasons. The outcome was “revolving-door” commands. As an enlisted man recalled, ”During my year in-country I had five second-lieutenant platoon leaders and four company commanders. One CO was pretty good …All the rest were stupid.”(19)

Aggravating this was the contradiction that guaranteed opposition between officers and men in combat. Officer promotions depended on quotas of enemy dead from search-and-destroy missions. Battalion commanders who did not furnish immediate high body counts were threatened with replacement. This was no idle threat — battalion commanders had a 30-50% chance of being relieved of command.

But search-and-destroy missions produced enormous casualties for the infantry soldiers. Officers corrupted by career ambitions would cynically ignore this and draw on the never-ending supply of replacements from the monthly draft quota.(20)

Officer corruption was rife. A Pentagon official writes, “[the]stench of corruption rose to unprecedented levels during William C. Westmoreland’s command of the American effort in Vietnam.” The CIA protected the poppy fields of Vietnamese officials and flew their heroin out of the country on Air America planes. Officers took notice and followed suit. The major who flew the U.S. ambassador’s private jet was caught smuggling $8 million of heroin on the plane.(21)

Army stores (PXs) were importing French perfumes and other luxury goods for the officers to sell on the black market for personal gain. But the black market extended far beyond luxury goods: “The Viet Cong received a large percentage of their supplies from the United States via the underground routes of the black market: kerosene, sheet metal, oil, gasoline engines, claymore mines, hand grenades, rifles, bags of cement,” which were publicly sold at open, outdoor black markets.(22)

The troops were quickly disillusioned with a war in which American-made military materiel was being used against them. And then there were endless scandals: PX scandals, NCO-club scandals, sergeant-major scandals, M-16 jamming scandals. In interviews, when Vietnam veterans were asked what stood out about their experience, a repeated answer was “the corruption.”(23)

>p?The ethics of the officer corps imitated those of the business elite they served. They were corrupted by six-month command tours while their men served a year, by career advancement at the expense of troop welfare, by black market profiteering, and by living in luxury in the midst of combat troop slaughter. The corruption of the officers, combined with the combat plan that avoided officer casualties while guaranteeing the slaughter of their men, produced explosive results.

A Ruling-Class Strategy

“We know we can’t win a ground war in Asia.” —Vice President Spiro T. Agnew on Face the Nation (CBS-TV}, May 3, 1970(24)

The political and military position of the United States was hopeless from the moment it entered the war. It was fighting to protect capitalism and empire. The Vietnamese were fighting to reunify their country and break free of foreign control. The American-controlled government of South Vietnam was the political representative of the landlord class, which took 40 to 60% of the peasants’ crop as rent. In National Liberation Front (NLF)-controlled territory, rents were lowered to 10%, creating enormous peasant support for the Communist insurgency.(25)

As the NLF expanded their areas of control, it became increasingly difficult for the landlords to collect rents. They therefore struck a fateful bargain with their government: the army would collect the peasants’ rent in return for a 30% cut, which was to be split three ways between the government, the officers and the troops. Rent collection became more important to the army than fighting. The corrupt South Vietnamese government and its army were little more than tax collectors for the landlords. The enormous economic and military power of U.S. imperialism was no stronger than the social relations of its most corrupt and reactionary colonial clients.(26)

The war was fought by NLF troops and peasant auxiliaries who worked the land during the day and fought as soldiers at night. They would attack ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) and American troops and bases or set mines at night, and then disappear back into the countryside during the day.

In this form of guerrilla war, there were no fixed targets, no set battlegrounds, and there was no territory to take. With that in mind, the Pentagon designed a counterinsurgency strategy called “search and destroy.”

Without fixed battlegrounds, combat success was judged by the number of NLF troops killed — the body count. A somewhat more sophisticated variant was the “kill ratio” — the number of enemy troops killed compared to the number of Americans dead. This “war of attrition” strategy was the basic military plan of the American ruling class in Vietnam.(27)

For each enemy killed, for every body counted, soldiers got three-day passes and officers received medals and promotions. This reduced the war from fighting for “the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese” to no larger purpose than killing.

Any Vietnamese killed was put in the body count as a dead enemy soldier, or as the Gls put it, “if it’s dead, it’s Charlie” (“Charlie” was GI slang for the NLF). This was an inevitable outcome of a war against a whole people. Everyone in Vietnam became the enemy — and this encouraged random slaughter. Officers further ordered their men to “kill them even if they try to surrender — we need the body count. ”It was an invitation to kill indiscriminately to swell a tally sheet.(28)

Some enlisted men followed their officers into barbarism. The most infamous incident was the genocidal slaughter of the village of My Lai, where officers demanded that their men kill all inhabitants — more than 400 women, children, infants and old people. Only one minor officer, Lt. Calley, received a sentence for this Nazi-like war crime. President Nixon quickly pardoned him.(29) At that point, 32% of the American people thought high government and military officials should be tried for war crimes.

Rather than following their officers, many more soldiers had the courage to revolt against barbarism.(30)

Ninety-five percent of combat units were search-and-destroy units. Their mission was to go out into the jungle, hit bases and supply areas, flush out NLF troops and engage them in battle. If the NLF fought back, helicopters would fly in to prevent retreat and unleash massive firepower — bullets, bombs, missiles. The NLF would attempt to avoid this, and battle generally only occurred if the search-and-destroy missions were ambushed. Ground troops became the live bait for the ambush and firefight. Gls referred to search and destroy as “humping the boonies by dangling the bait.”(31)

Without helicopters, search and destroy would not have been possible — and the helicopters were the terrain of the officers. “On board the command-and-control chopper rode the battalion commander, his aviation-support commander, the artillery-liaison officer, the battalion S-3 and the battalion sergeant major. They circled … high enough to escape random small-arms fire.” The officers directed their firepower on the NLF down below, but while indiscriminately spewing out bombs and napalm, they could not avoid “collateral damage” — hitting their own troops. One-quarter of the American dead in Vietnam was killed by “friendly fire” from the choppers. The officers were out of danger, the “eye in the sky,” while the troops had their “asses in the grass,” open to fire from both the NLF and the choppers.(32)

When the battle was over, the officers and their choppers would fly off to base camps removed from danger while their troops remained out in the field. The class relations of any army copy those of the society it serves, but in more extreme form. Search and destroy brought the class relations of American capitalism to their ultimate pitch.

Of the 543,000 American troops in Vietnam in 1968, only 14% (or 80,000) were combat troops. These 80,000 men took the brunt of the war. They were the weak link, and their disaffection crippled the ability of the world’s largest military to fight. In 1968, 14,592 men — 18% of combat troops — were killed. An additional 35,000 had serious wounds that required hospitalization. Although not all of the dead and wounded were from combat units, the overwhelming majority were.

The majority of combat troops in 1968 were either seriously injured or killed. The number of American casualties in Vietnam was not extreme, but as it was concentrated among the combat troops, it was a virtual massacre. Not to revolt amounted to suicide.(33)

Officers, high in the sky, had few deaths or casualties. The deaths of officers occurred mostly in the lower ranks among lieutenants or captains who led combat platoons or companies. The higher-ranking officers went unharmed. During a decade of war, only one general and eight full colonels died from enemy fire.(34) As one study commissioned by the military concluded, “In Vietnam … the officer corps simply did not die in sufficient numbers or in the presence of their men often enough.”(35)

The slaughter of grunts went on because the officers never found it unacceptable. There was no outcry from the military or political elite, the media or their ruling-class patrons about this aspect of the war, nor is it commented on in almost any history of the war. It is ignored or accepted as a normal part of an unequal world, because the middle and upper class were not in combat in Vietnam and suffered no pain from its butchery. It never would have been tolerated had their class done the fighting. Their premeditated murder of combat troops unleashed class war in the armed forces. The revolt focused on ending search and destroy through all of the means the army had provided as training for these young workers.

Tet — The Revolt Begins

“We have known for some time that this offensive was planned by the enemy … The ability to do what they have done has been anticipated, prepared for, and met … The stated purposes of the general uprising have failed … I do not believe that they will achieve a psychological victory.” —President Lyndon B. Johnson, February 2, 1968(36)

The Tet Offensive was the turning point of the Vietnam War and the start of open, active soldiers’ rebellion.

At the end of January 1968, on Tet, the Vietnamese New Year, the NLF sent 100,000 troops into Saigon and 36 provincial capitals to lead a struggle for the cities. The Tet Offensive was not militarily successful, because of the savagery of the U.S. counterattack. In Saigon alone, American bombs killed 14,000 civilians. The city of Ben Tre became emblematic of the U.S. effort when the major who retook it announced that “to save the city, we had to destroy it.”

Westmoreland and his generals claimed that they were the victors of Tet because they had inflicted so many casualties on the NLF. But to the world, it was clear that U.S. imperialism had politically lost the war in Vietnam. Tet showed that the NLF had the overwhelming support of the Vietnamese population — millions knew of and collaborated with the NLF entry into the cities and no one warned the Americans.

The ARVN had turned over whole cities without firing a shot. In some cases, ARVN troops had welcomed the NLF and turned over large weapons supplies. The official rationale for the war, that U.S. troops were there to help the Vietnamese fend off Communist aggression from the North, was no longer believed by anybody. The South Vietnamese government and military were clearly hated by the people.(37)

Westmoreland’s constant claim that there was “light at the end of the tunnel,” that victory was imminent, was shown to be a lie. Search and destroy was a pipe dream. The NLF did not have to be flushed out of the jungle — it operated everywhere. No place in Vietnam was a safe base for American soldiers when the NLF so decided.

What, then, was the point of this war? Why should American troops fight to defend a regime its own people despised? Soldiers became furious at a government and an officer corps who risked their lives for lies.

Throughout the world, Tet and the confidence that American imperialism was weak and would be defeated produced a massive, radical upsurge that makes 1968 famous as the year of revolutionary hope. In the U.S. army, it became the start of the showdown with the officers.

Within three years, more than one-quarter of the armed forces was absent without leave (AWOL), had deserted or was in military prisons. Countless others had received “Ho Chi Minh discharges” for being disruptive and troublemaking. But the most dangerous forces were those still active in combat units, whose fury over being slaughtered in useless search-and destroy missions erupted in the greatest rebellion the U.S. army has ever encountered.(38)

Notes

- Colonel Robert D. Heinl, Jr., “The Collapse of the Armed Forces,” Armed Forces Journal, June 7, 1971, reprinted in Marvin Gettleman, et al., Vietnam and America: A Documented History (New York: Grove Press, 1995), 327.

back to text - Quoted in William G. Effros, Quotations: Vietnam, 1945-70, New York: Random House, 1970), 172.

back to text - Christian G. Appy, Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam (Chapel Hill: University ofNorth Carolina Press, 1993), 18.

back to text - Appy, 24-27 and James William Gibson, The Perfect War: Technowar in Vietnam (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1986), 214-15.

back to text - James Fallows, “What Did You Do in the Class War, Daddy?” Vietnam: Anthology and Guide to a Television History, Steven Cohen, ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983), 384.

back to text - Appy, 26. The rate of Black deaths in Vietnam in 1965 was double their army participation rate, but was brought down to normal proportions within three years because of Black soldiers’ struggle against racism. The struggle for Black liberation within the army in these years deserves another article of its own. For more infonnation, see David Cortright, Soldiers in Revolt: The American Military Today (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1975), 201-16.

back to text - Appy, 36-37.

back to text - Larry G. Waterhouse and Mariann G. Wizard, Turning the Guns Around: Notes on the GI Movement (New York: Praeger, 1971), 136-38.

back to text - Camp News, January 15, 1971, and March 15, 1971.

back to text - Vietnam GI, May 1970. Of the hundreds of underground GI newspapers, only a handful appeared regularly over time and had readership beyond a particular base or army division. Of these, the most important were Camp News, The Bond and Vietnam GI. Vietnam GI had the largest following in Vietnam due to its ability to put a clear, radical political analysis in language that connected with the experiences of the grunts. It was put out by Vietnam vets and by former members of the left wing of the Young People’s Socialist League, who were loosely associated with, although organizationally independent frorn, the current that became the American International Socialists.

back to text - Kirn Moody, “The American Working Class in Transition,” International Socialism, No. 40 (Old Series), Oct./Nov. 1969, 19.

back to text - Effros, 209.

back to text - Appy, 25-26.

back to text - Cincinnatus, Self-Destruction, The Disintegration and Decay of the United States Army During the Vietnam Era (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981), 155.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 139.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 145.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 146.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 147-48.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 157-59.

back to text - Gibson, 116.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 54-56.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 55.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 53.

back to text - Effros, 217.

back to text - Gibson, 71.

back to text - Gibson, 74-75.

back to text - Gibson, 101-15 and Cincinnatus, 75-82.

back to text - Appy, 155-56, and Cincinnatus, 84-85.

back to text - Seymour M. Hersh, “What Happened at My Lai?” in Gettlernan, 410-24.

back to text - Cohen, 378.

back to text - Appy, 152-58, 182-84.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 62-63, 70.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 147, 161.

back to text - Cincinnatus, 155.

back to text - Richard A. Gabriel and Paul L. Savage, Crisis in Command: Mismanagement in the Army (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978), 16.

back to text - Effros, 89.

back to text - R. Gibson. See Chapter 6, “The Tet Offensive and the Production of a Double Reality.”

back to text - Robert Musil, “The Truth About Deserters,” The Nation, April 16, 1973 and for “Ho Chi Minh” discharges, Steve Rees, “A Questioning Spirit: Gls Against the War” in Dick Custer, ed., They Should Have Served that Cup of Coffee (Boston: South End Press, 1979), 171.

back to text

September-October 2025, ATC 238