Against the Current No. 238, September-October 2025

-

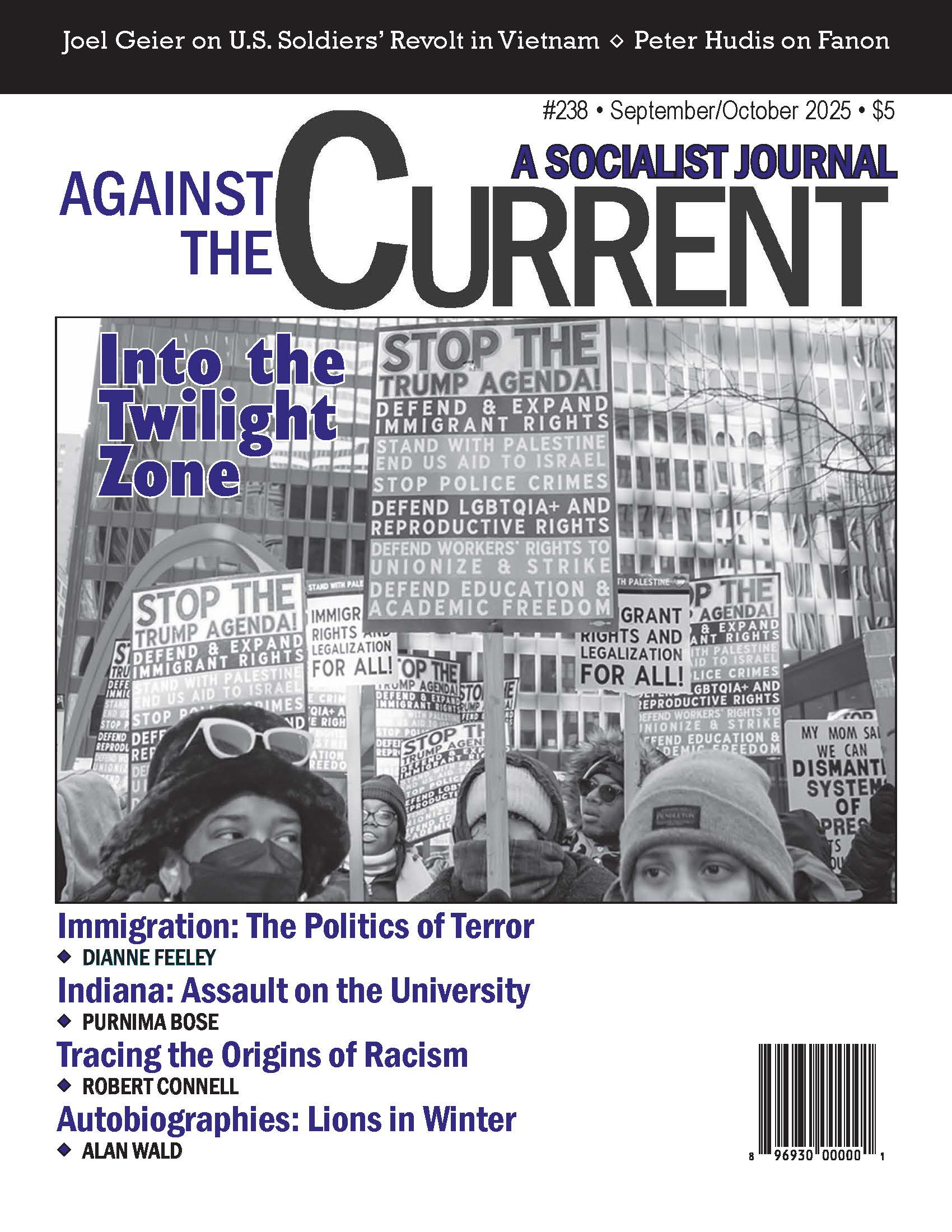

In Twilight-Zone USA

— The Editors -

Indiana's Assault on Public Education

— Purnima Bose -

Trump's Brutal Immigration Policies

— Dianne Feeley -

Team Trump's Immigration Protocols

— Dianne Feeley -

ICE Terror Unleashed in Los Angeles

— Suzi Weissman interviews Flor Melendrez -

From Welfare Toward A Socialist Future

— David Matthews -

Honoring Anti-Fascist Resistance

— Jason Dawsey -

What Future for the Middle East

— Valentine M. Moghadam -

Bloody Amputation: Trump’s “Peace” for Ukraine

— David Finkel - Vietnam

-

The Soldier's Revolt, Part I

— Joel Geier - Review Essays

-

Lions in Winter: Longtime Activist Lives on the Left

— Alan Wald -

Fascism, Jim Crow & the Roots of Racism: Tracing the Origins

— Robert Connell - Reviews

-

Republican and Revolutionary?

— David Worley -

Frantz Fanon in the Present Movement

— Peter Hudis -

The Power of Critical Teacher: About Palestine & Israel

— Jeff Edmundson -

Hearing the Congo Coup

— Frann Michel

David Worley

Citizen Marx

Republicanism and the Formation of Karl Marx’s Social and Political Thought

By Bruno Leipold

Princeton University Press, 2024, 440 pages, $39.95 hardback.

THE AUTHOR OF this review recently facilitated for the Marxist Education Project a small study group reading Citizen Marx. This review is partly informed by that experience.

Written in an accessible style, Citizen Marx is useful for activists and scholars in establishing the historical context of Karl Marx’s revolutionary politics and parsing out Marx’s motivating principles.

In Bruno Leipold’s words, his purpose in writing Citizen Marx was to reclaim “the idea that freedom lies at the heart of a social critique of capitalist domination and … democratic institutions are essential to overcome that domination.” (37)

Leipold aims to refute critics like Hannah Arendt who claim that Marx’s critical dissection of the modern world, being centered on social class relations, glosses over the importance of institutions of government. Further, she posits, Marx was indifferent to personal freedom even advocated for an authoritarian system.

The Early Marx

Many readers perhaps will be fascinated by correspondences between the issues that divided Marx and his colleagues from radical republicans like Karl Heinzen, who rejected Marx’s vision of communism in favor of something like New Deal liberalism, and the political debates of our own time.

Marx the republican: “Citizen” was a form of address adopted in revolutionary France as an alternative to the obsequious “monsieur.” It came to be used among all kinds of republicans throughout the 19th century. Marx was often addressed and referred to as Citizen Marx in sympathetic correspondence and literature.

For Leipold, the use of the term identifies Marx as a “republican,” a supporter of a system of government that is created by the citizens, exists to serve the citizens, and is answerable to the citizens. This is opposed to systems of government that claim power by “divine right,” in which subjects live to serve the rulers.

But to call Marx a “republican” is also to establish that Marx’s revolutionary vision throughout his career was always for a state power that could promote human freedom through democratic laws and institutions. Marx always resisted sloganeering to “abolish the state,” “abolish the law,” as meaningless.

For those readers who are not professional scholars, Citizen Marx introduces a number of 19th-century revolutionists prominent in Marx’s time but now largely forgotten: Helen Macfarlane and George Harney (who published the first English translation of the Communist Manifesto), William Linton, Guiseppe Mazzini, Félicité de Lamennais, Arnold Ruge, Karl Heinzen, et al.

Europe mid-19th century was in political and social turmoil, torn between the progressive ideas and institutions of the French Revolution of 1789 and the tattered remnants of the pre-modern world, restored, if not very convincingly, after the defeat of France in 1814. Republicans were those who rejected these restorations of medieval privileges. Basing themselves in the French Revolution, they insisted on constitutional government and general civil liberty. At their best, they called for political democracy, “liberté, egalité, humanité,” to use the phrase of Lamennais.

Leipold’s book traces Marx’s development as a revolutionist from liberal republican to republican revolutionist to communist republican. He discusses how Marx’s ideas changed in the context of the social upheavals of the mid-19th century and the debates among reformers and revolutionists about how to respond to these upheavals.

The depth of Leipold’s scholarship is truly impressive, ranging from the classics of political writing in the 19th and 20th centuries through 19th-century journalism in several languages, to 20th-21st century academic writing and socialist apologetics. Unfortunately, the book lacks a bibliography, so sources have to be traced through the many footnotes.

Citizen Marx is divided into three sections with a preface and a postface. It is essentially chronological, but with a lot of backtracking and therefore some repetitiveness. Each section ends with a “coda,” a short summary.

The Introduction surveys republican political movements in western Europe and the UK in the 19th century. It summarizes Karl Marx’s lifelong political and theoretical support of democratic republicanism and the influence of his theory of state and revolution beyond his own times.

Part 1: “The Democratic Republic (1843-1845)” describes the stages of Marx’s personal political evolution:

1) Radical proponent of constitutional government and “liberty, equality, and humanity” as the basis of a free society;

2) Realization (with some other Young Hegelians) that political freedom (civil liberty) and economic freedom (free enterprise) are not sufficient to realize human freedom, and so, embrace of communism, common ownership of the means of production, as necessary for a truly free society of equal citizens and therefore the ultimate goal of a European revolution;

3) Perhaps most important for Marx’s future political and intellectual development, the conclusion that the modern industrial working class (proletariat) is the true revolutionary subject in a social universe no longer dominated by feudal lords but by the owners of capital.

Defining Freedom

In his first chapter, Leipold explicates a Marxian definition of “freedom” as “non-domination/non-dependency,” distinguishing this notion from the utilitarian/libertarian concept of freedom, described as “non-interference.” He argues that Marx’s agitation both for a democratic republic and against private property in the form of capital is rooted in this notion of freedom.

For Marx, political freedom (civil rights, legal equality) by itself does not erase the domination of the workers in the workplace by the boss, the dependence of the class of workers on the owners of capital, or the domination of society as a whole by the whims of capital markets. This idea of freedom is at the heart of Marx’s communism and his idea of a “social republic.”

Leipold explains how and why in 1841-45 Marx broke with his Young Hegelian collaborators like Arnold Ruge and Moses Hess and found new ones, notably Frederick Engels. Engels helped convince him of the revolutionary potential of the proletariat, the central theme of the co-written Manifesto of the Communist Party.

Convinced that narrow political liberty leaves the social domination of private wealth untouched — and cannot be the road to freedom — Marx embraced communism. He did so not as a utopian experiment but as a political communism, a workers’ republic that would seize and run collectively the already collectivized production of the modern industrial system owned by private capital.

While the Chartists in the UK were the first political organization rooted in the industrial working class, Marx’s League of Communists was the first political organization hoping to organize this class to take the lead in a republican revolution. Its Manifesto offered a social scientific criticism of the modern world, grounding the movement for a European revolution in a theory of history that transcends the moralistic appeals of both utopian communists and liberal republicans.

Leipold’s sources include Marx’s notebooks and unpublished writings from these years. These include studies of Aristotle, Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Rousseau, James Hamilton, and Marx’s own Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (only the Introduction was ever published until recently). The seeds of Marx’s materialist theory of history are found in these writings.

Through Engels more than anyone, Marx became acquainted with the conditions and revolutionary potential of the rising industrial working class (proletariat) in the struggles for democracy.

In an 1845 article, Marx first argued that revolutions take place when a rising social class can project its class interest as the general interest of the society. The proletariat was the revolutionary class of the rising industrial society and its liberation required the abolition of private property.

The “political revolution” must have a “social soul.” This latter was part of what led Marx to break with his colleague Arnold Ruge. (At this point, Leipold interjects a generally sympathetic biography of Ruge, interesting for its discussion of the Young Hegelian movement. A similar treatment of P.J. Proudhon would have been appropriate too. He and Marx were never colleagues, but Marx’s move toward communism was certainly influenced by Proudhon’s book about private property. Marx had hoped to collaborate with Proudhon when he first went to Paris.)

Part 1 of Citizen Marx ends with an informative discussion of the 1844 “Economic-Philosophic Manuscripts” and the beginnings of Marx’s critique of political economy. This became a project that in a few years would dominate his life.

A theme that Leipold unfolds is Marx’s realization that unfreedom, if you will, is not just direct domination by the other, but alienation and dependency. Modern wage workers are not “owned” by the capitalist as slaves are owned, but forced to alienate their labor power in order to survive. Their dependence on the needs and whims of the employers subjects them to the domination of the latter just as surely.

Revolutionary Republicanism

Part 2: “The Bourgeois Republic,” puts Marx-Engels’ newly proclaimed communism in the revolutionary politics that swept all of Europe in 1848. (There is a very rich history here, and Leipold seems to assume that readers are familiar with it, as evidenced by his use without definition of Vormaerz, referring to Europe in the period just before March 1848. For readers unfamiliar with this history, it can be a little hard to follow.)

Chapter 4 centers on the Manifesto of the Communist Party and its contrast of revolutionary Republican socialism with apolitical “true socialism.” Leipold restates Marx’s argument for the necessity but insufficiency of the “bourgeois republic.

Chapter 5 describes in detail the controversies between the League of Communists and other radical republicans in the UK and Germany 1848-1852. This includes debates about the “social soul” of republican politics, the “people” versus the proletariat as the revolutionary subject, and the universalization of private property favored by liberals versus abolition of private property in production.

Notably, several pages here are devoted to Karl Heinzen, a lifelong radical republican, who criticized Marx’s communism fiercely, using many arguments familiar to us today.

Leipold introduces here other themes that characterize Marx’s criticism of bourgeois democracy. “Representative” institutions dominated by professional politicians and bureaucrats are more beholden to their financiers than to the public. Rather than involving citizens in their government, elections actually separate them. These are points to which the author returns at the end of the book.

In Chapter 6, “Chains and Invisible Threads,” Citizen Marx offers a deep discussion of Marx’s attack on capitalism as a social system built on subornation of the majority of society by a small minority. This is not a system of “freedom” at all but a new kind of slavery. This is the message of Marx’s great intellectual project, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy.

Leipold emphasizes that Marx’s writings on political economy were all written in the service of his lifelong political work to encourage the modern working class (proletariat) to revolt against the modern ruling power (capital) in order to make possible a truly free society.

The power of capitalists as a new ruling class is seen in the private ownership of social means of production, the systematic exploitation by capital of wage labor to extract surplus value, the daily, hourly dictatorship of the workplace, and the role of markets and competition in reinforcing the domination of society by capital accumulation.

Citizen Marx describes how Marx took the lead in organizing the International Working Mens Association (1864-1876) as a vehicle for supporting the struggles of labor against capital.

Marx, in theory and practice, works for the ultimate emancipation of human labor from the oppression of necessity and servility, from the “invisible, intangible, silent despot,” the impersonal power of the capitalist market that unpredictably raises up and throws down nations and individual lives.

The Example of the Paris Commune

Part 3: “The Social Republic” picks up Marx’s renewed interest in the republican revolutionary project as a response to the Paris Commune in 1870. In short, the citizens of Paris being armed to defend against a siege by German invaders, resisted being disarmed by the provisional French government seated at Versailles.

In the process, they elected their own provisional government, the Commune de Paris, and proceeded to implement a radical republican constitution.

Although followers of Marx were not prominent in the Commune (old rivals like Louis Blanqui and followers of Proudhon were), Marx immediately used all his influence to defend it against the regime of bankers, landlords and industrialists seated in Versailles.

Marx saw in the Commune constitution (not by the way “socialist”) what he had always considered key elements of a truly democratic republic: universal (male) suffrage; limiting salaries of elected officials and other office holders to the salaries of skilled workers; short terms of office and right of voters to recall elected officials at any time; the unity of legislative and executive power in the governing council; neighborhood control of police; free and secular education, etc.

To Marx, the Commune represented a “social republic.” Leipold illustrates with a little chart the political innovations that Marx, inspired by the Commune, ascribed to his Social Republic. (page 362) As in the rest of the book, the author brings into his discussion a wide array of theoretical arguments about representative government, from Rousseau to contemporary works like Bernard Manin’s Principles of Representative Government.

Finally, Marx concluded, the proletarian republic required more than parliamentary forms or electing socialists into an existing political system. It required the “smashing” of the existing political system dominated by the power of the bourgeoisie and its replacement by a different system that would guarantee the political power of ordinary citizens. It required a republic based on collective self-determination, a participatory democracy.

As we know, the Paris Commune was crushed. In time, the modest successes of Marxist Social Democratic parties in parliamentary politics led the socialist movement to lose interest in Marx’s vision of a decentralized, more directly democratic state.*

It is in this section that Leipold tackles Marx-Engels’ controversial phrase “dictatorship of the proletariat,” used at times to describe a working-class revolutionary government. Given the inevitable association of Marxian socialism with authoritarian states based on the model of the USSR, Leipold employs the usual (legitimate if not entirely consistent) apologetics, citing the late Hal Draper’s extensive discussion in volume 3 of Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution.

That is, existing governments are “dictatorships of the bourgeoisie” even if they are legalistic and democratic in form; the word dictatorship simply refers to the hegemony of the ruling class over the state.

Or, the “dictatorship” refers to a temporary period in which the working class is establishing its power against, the resistance of the old ruling class. Or the “dictatorship of the proletariat” is meant to contrast to the dictatorship over the society (including the proletariat) proposed by elitist revolutionists like Louis Blanqui.

In Citizen Marx, readers are left to pick their preferred interpretation — or all three could be correct depending on context. Leipold argues convincingly that Marx himself saw the social republic as a democratic and open society, not a police state.

It’s worth noting that Leipold doesn’t give much account of Marx’s struggles with Mikhail Bakunin and his followers. The International Working Men’s Association was much disrupted and finally dissolved due to the attempt by Bakunin and his shadowy society of “anarchists” to take control of it. Bakunin wrote a bitter attack on Marx, Statism and Society, arguing specifically that Marx’s “proletarian state” would be nothing but a “dictatorship over the proletariat.”

Marx never published (although he did make notes for) a rebuttal, but Bakunin’s critique had great influence on the Syndicalist movement. That critique played a big role in proletarian struggles in a few countries in later years. More could have been said about it in this book.

Citizen Marx also gives short shrift to practical criticisms that could be made of Marx’s social republic.

For example, Marx had little time for certain mainstays of bourgeois republican theory such as separation of powers, checks and balances, etc. But there are very strong arguments that these impediments to the General Will can ensure more thoughtful and reasoned public policies.

Likewise, Marx had little use for bureaucratic expertise, but is it the case that policies about environmental protection, mass transportation, land use management, etc. could be executed competently by people without special training? And how is it possible to “smash” the existing state while maintaining necessary public services.

A more critical discussion of these issues would add to the credibility of Citizen Marx. All in all though, Citizen Marx is a worthwhile excursion into Karl Marx’s theory of state and revolution.

Leipold, currently assistant professor of political theory at the London School of Economics and Political Theory, exhibits impressive scholarship throughout the volume. His treatment of Marx’s antagonists is mostly fair.

Above all, this study brings to the fore again a fact that has been covered by the detritus of 20th-century wars and revolutions: Marx’s communism was rooted in a vision of human freedom.

*In the early 20th century, revolutionists in Russia saw their own workers organize councils (“soviets”) to govern localities as the Tsarist state crumbled. Lenin and Trotsky (separately) identified the soviets with the Paris Commune and proposed this as the basis of a new kind of government. Their ideas were presented in Lenin’s 1917 pamphlet, The State and Revolution. But the Russian version of councils withered away in the civil war and subsequent power struggles among the revolutionaries. It seems safe to say that certain practical difficulties with this model of government also contributed to the replacement of the soviets in the USSR by a more standard parliamentary system in the 1930s.

This is not a discussion taken up in Citizen Marx, which is fair enough since it’s a book about Marx.

September-October 2025, ATC 238