Against the Current No. 236, May/June 2025

-

Lessons of Abductions and Terror

— The Editors -

Vets Mobilize vs. DOGE

— Steve Early & Suzanne Gordon -

Upholding Reproductive Rights in Ohio & Beyond

— Marlaina A. Leppert-Miller -

The Humanities After Gaza

— Cynthia G. Franklin -

On Social Movement Media: Learning from Krupskaya & Lenin

— Promise Li -

The Rule, Not the Exception: Sexual Assault on Campus

— M. Colleen McDaniel & Andrew Wright -

Diktats, DOGEs, Dissent & Democrats in Disarray in the Era of Trump

— Kim Moody -

A Setback for Auto Workers' Solidarity

— Dianne Feeley - Columbia Jewish Students for Mahmoud Khalil

-

Plague-Pusher Politics

— Sam Friedman - Guatemala Human Rights Update

- A Remembrance

-

Fredric Jameson's Innovative Marxism

— Michael Principe - Reviews

-

The New Nuke Revival

— Cliff Conner -

Power in the Darkness

— Owólabi Aboyade -

Racial Capitalism Dissected

— James Kilgore -

An Important Critique of Zionism

— Samuel Farber -

What's Possible for the Left?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Behind the Immigration Crisis

— Folko Mueller

Steve Early & Suzanne Gordon

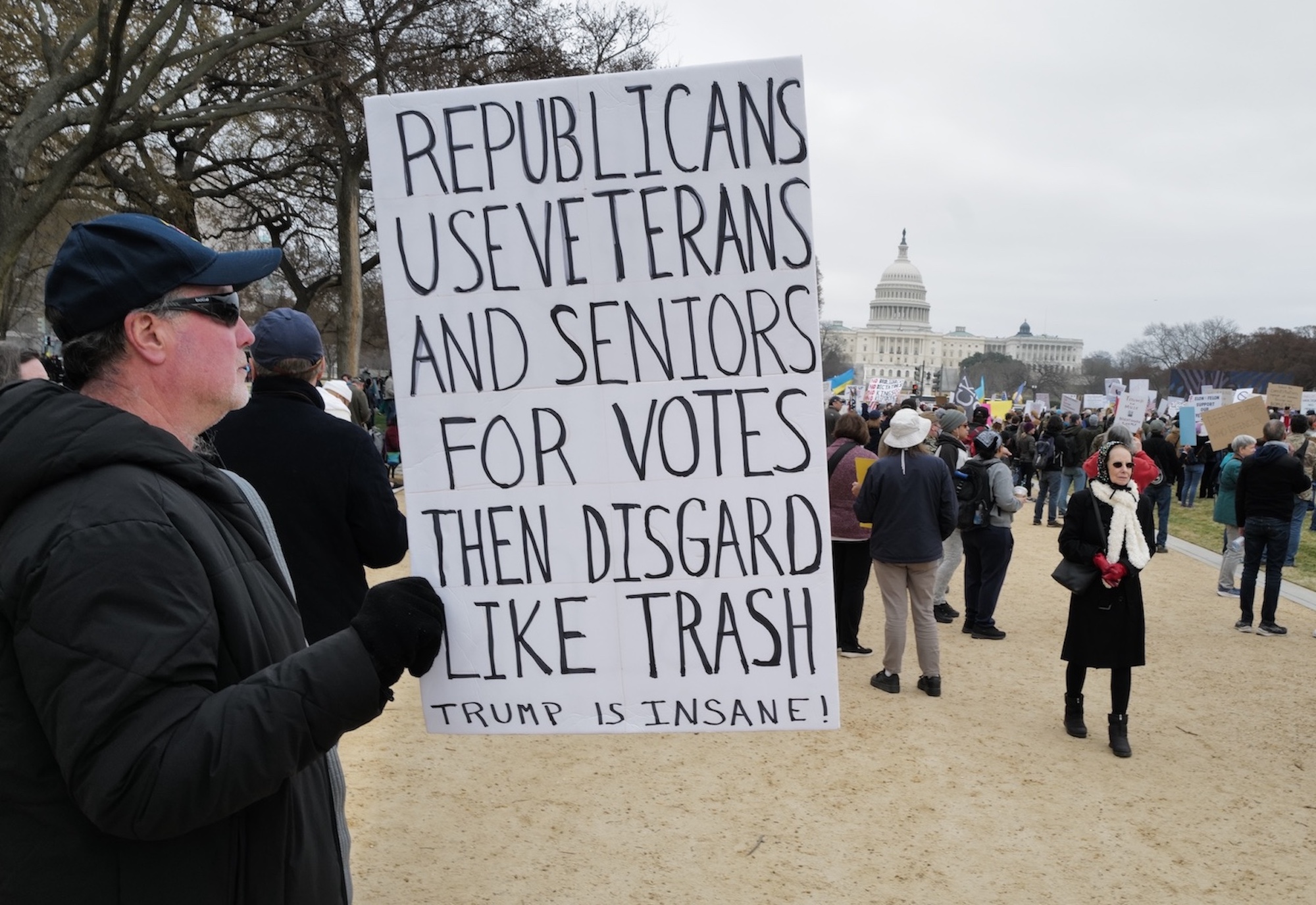

ON MARCH 14, a much-decorated former Capitol police officer was on his way to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. to join a protest against down-sizing of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) by the Trump Administration.

Among the thousands gathered there were more than a few American flag wavers, decked out in camo and other forms of apparel favored by military veterans. The mere sight of them gave Harry Dunn a “PTSD moment.” As he explained later, “the last time I saw a crowd like this, they were beating the shit out of me and my co-workers at the Capitol.”

What Dunn encountered was not a re-union of now pardoned January 6 rioters, but an increasingly common sight outside VA hospitals and other federal buildings around the country: military veterans, their families, and VA care-givers rallying against Trump-Musk attacks on the nation’s largest public healthcare system.

These reinforcements are a welcome addition to the ranks of “Save Our VA” campaigners from Veterans for Peace and Common Defense, who have been sounding the alarm about VA privatization threats for years. In early March, Vietnam veteran Paul Cox was visiting a terminally ill friend at a VA facility in St. Louis. Afterwards, he ran into a woman in the hospital parking lot, who handed him a leaflet.

“VA workers are being fired,” it said. “This can hurt your care. This is an assault on the VA. Call or email your Senators and Representatives as soon as you can.”

Cox is a leading member of VFP long active in its Save Our VA (SOVA) committee; so, he has distributed similar appeals on many occasions. When the longtime VFP activist asked the lone hand biller whether she belonged to any labor or veterans’ groups, he found she was acting entirely on her own.

Reading about President Trump’s mass firing of federal employees, she became very worried about the impact on local VA care for her husband. She had typed up the flyer herself, taken it to a copy shop, and began hand billing other patients, staff, and family members.

Several weeks later, at the same location, hundreds of demonstrators gathered to denounce Elon Musk and his tech industry underlings at the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).

As one vet attending that protest told the press: “We’re not going to stand quietly by while the VA is dismantled, and benefits are taken away…They just come in and start pulling strings and wires on the wall to see what happens. But this isn’t X. It isn’t Twitter. It’s not me losing a tweet. It’s guys dying.”

VA Headquarters Leak

This growing backlash began in response to the indiscriminate dismissal of 2,400 VA probationary workers, including many former service members. That group — along with new hires in five other federal departments — got a temporary reprieve, in the form of a March 13 reinstatement order issued by U.S. District Court Judge William H. Alsup in San Francisco. [On April 8, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed Judge Alsup’s reinstatement order. —ed.]

However, as Alsup warned the union plaintiffs in this case, the VA and other agencies still have the ability to downsize based on future Reduction in Force (RIF) plans that are “done right.”

A March 4 headquarters memo revealed that new VA Secretary Doug Collins plans a RIF from 480,000 employees to 399,957, starting in August. This return to the agency’s headcount six years ago will, according to that leaked document, “eliminate waste, reduce management and bureaucracy…and increase workforce efficiency.”

In an opinion piece for The Hill, Collins pledged to do this “without making cuts to healthcare or benefits” and warned critics that “we will be making major changes. So get used to it.”

Others on the Hill, and their constituents, are not happy with that response. “The VA,” warns Mark Takano (D-CA) “is on the precipice of destruction” from “a senseless reduction in force.”

According to this ranking member of the House Veterans Affairs Committee, the VA-run Veterans Health Administration (VHA) will be seriously disrupted — particularly for those among its nine million patients who have service-related conditions due to past toxic exposures in combat zones or on U.S. military bases.

The VA has had a big influx of disability benefit claimants since Congressional passage of the Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act in 2022.

Nearly a million vets have since qualified for VHA care, due to medical conditions acquired while serving near burn-pits in the Middle East or on military bases in the U.S. with poisoned soil or water. They join older vets whose health was damaged by Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam or other forms of chemical contamination during the first Gulf War.

With VA workforce cuts of nearly 20% now looming, advocates for veterans fear that PACT Act implementation will be disrupted, even with a projected 10-year allocation of $280 billion to fund its expanded coverage. As a NY Times investigation has confirmed, the VA’s initial job cuts in early 2025 and its DOGE-driven cancellation of hundreds of agreements with outside contractors has already had a chaotic, ripple effect.

Longer term, the VHA’s role as a medical research powerhouse, leading provider of clinical education for healthcare professionals, and backup public hospital system during pandemics or other emergencies will be jeopardized. And veterans who have filed tens of thousands of disability claims with the VA-run Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) will face longer delays getting them approved.

Labor-Management Uncertainty

One regional VA administrator we interviewed (who asked not to be identified) described the widespread uncertainty among his/her colleagues about how to submit plans, demanded by VA headquarters in Washington, for further staffing cuts.

“Are we following Office of Management and Budget (OMB) rules, or the rule of law, which requires that we follow certain guidelines, for example, people with the most seniority are the last to go, employees who are veterans are the last to go, employees with high performance ratings ditto?”

To share information and get answers to personnel questions like these, nearly 20,000 people have joined a Reddit group called VeteransAffairs. It’s moderated by a VHA pharmacist and Tennessee community college teacher David Carson, a former VBA claims processor.

A combat vet with PTSD, Carson was fired in 2017 — in part because of a Facebook post he had written with the hashtag #AssassinateTrump, which some of his co-workers, and management, found to be threatening.

Learning from that experience, Carson is now trying to “create a safe, helpful, and respectful [online] community” where others can get the benefit of his experience helping vets qualify for VA benefits and fight unfair dismissals. As one grateful subreddit user in Salt Lake City told The Times, “it just gives you an idea of what other people at the V.A. are going through, that you’re not alone.”

Among career employees like these, there is little confidence that Republican political appointees — eager to impress DOGE and the White House by meeting their staffing cut quotas — have any real understanding of who is “mission critical” at the VA and who is not. For example, many employees illegally fired by the first Trump Administration, under the VA Accountability and Whistleblower Act of 2017, were house-keepers and food service workers considered easily disposable.

As one VHA manager asks now, who is going to feed hospitalized veterans and keep facilities clean when you lay-off and don’t replace such support staff members? Who is going to change the sheets on their beds or sanitize a room to prevent the spread of serious hospital acquired infections like MRSA or Clostridium difficile (C-Diff)?

Another VA official pointed out the adverse safety impact of Collins’s recent abrupt cancellation of multiple contracts with needed private sector vendors. One contract — since restored — was with an outside firm supplying radiation safety officers for VHA oncology and imaging departments (a position outsourced because of difficulty hiring inhouse staff to fill this role).

No More Phoning It In?

A well-documented strength of the VHA is its telehealth services in areas like nephrology and kidney care. This consultative capacity is critical, one staffer told us, for veterans in rural states like Alaska, Montana or Wyoming and isolated places like Guam or even Hawaii, where there are very few nephrologists.

Yet Secretary Collins — an Air Force Reserve Colonel, Baptist minister, and former congressman with no healthcare experience — insists that such care delivery is easily reproducible in the private sector.

Many veterans with mental health conditions, also rely on VHA telehealth sessions with their therapists, who are in very short supply in many parts of the country. These patients suffer from depression, substance abuse, and a higher risk of self-harm than the general population.

The VHA has a major advantage over alternative providers of therapy, via telehealth, who also operate on a multi-state basis. In the private sector, if a doctor, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or therapist cares for an out-of-state patient, they must be licensed in both their own and that other state.

The VA has been uniquely empowered to establish national standards of practice for its health care professionals that enables them to work remotely, from home, while caring for patients, without regard to state licensing requirements (which remain a legal obstacle to other healthcare systems’ wider use of telemedicine).

Such advantages are little valued by right-wing operatives like Collins, who has now ordered mental health providers to return to work in VHA facilities — even if the only space available for them to conduct virtual psychotherapy with patients is cubicles in a large open office space, set up like a call center.

As new VA spokesman Peter Kasperowicz, a former Washington Examiner and Fox News reporter, informed The Times, on March 24, “Under President Trump, V.A. is no longer a place where the status quo for employees is to simply phone it in from home.”

Clinicians interviewed by the newspaper warn that such work location changes “will degrade mental health treatment, which already has severe staffing shortages” and trigger “a mass exodus of sought-after specialists like psychiatrists and psychologists.”

The result will be more costly referrals to private sector providers and longer wait times for appointments, particularly in rural areas and any part of the country with a shortage of mental health services for patients unable to pay out of pocket.

Claims Processing Delays?

Even before the arrival of DOGE cost cutters, VBA staff members faced the challenge of processing new PACT Act-related claims based on 23 medical conditions, ranging from bronchial asthma to various rare cancers, which are now considered presumptively related to either burn-pit exposure and other chemical exposures in the military.

VHA staffers fear that impending job cuts will make it harder for veterans to get medical exams enabling them to join registries maintained for victims of Agent Orange, Gulf War syndrome, burn-pit and asbestos exposure.

A survey of several thousand VA staffers conducted by the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) two years ago found that a majority of VBA respondents were experiencing unmanageable claims processing workloads. Even then, this was causing more than 60% to consider leaving their jobs.

A similar large majority of VHA participants in this survey said their facilities needed more frontline and administrative/support staff. But vacancies were not being filled, nor was sufficient recruitment of new staff underway. More than two-thirds reported that beds, units or programs in their facility had been closed due to local staffing shortages and budget deficits, even in places with continuing patient demand.

Life and Death Stuff

Three years later, VHA managers — not just union members — foresee such conditions getting much worse, not better. They express a particular concern about how cuts to research and direct care will adversely affect patients undergoing cancer treatment.

Patients on clinical trials or even undergoing traditional cancer treatment at the VHA can’t just switch providers overnight. If there is no longer sufficient staff to provide care, their clinical trial will be ended, with no guarantee of its continuation outside the VHA. Outside the veterans healthcare system, there can be much longer waits for an appointment with an oncologist.

“This is life and death stuff,” a VHA medical center administrator told us. “We don’t treat cancer because it’s benign, we treat it — and right away — because it can kill you right away.”

One 50-year old Army veteran well aware of the need for that kind of timely treatment is Jose Vasquez, executive director of Common Defense. On March 6, his group held a national emergency Zoom call on saving the VA with more than 350 participants from around the country.

Many on the call were surprised to see Vasquez lying in bed and dressed in a hospital johnny. “I am coming to you live from the Manhattan VA,” he explained. “I’ve just had surgery for pancreatic cancer and the idea that the Trump Administration would want to cut 83,000 positions and fire that many people from VA facilities is ludicrous. The VA just saved my life.”

“It’s getting real,” he warned. “They’re coming after our veterans’ benefits but we’re not going down without a fight” — a message echoed by other vets on the call. They pledged to rally their fellow vets and bombard politicians and the press with their own stories of life-changing experiences with VA programs and services.

One Common Defense activist already doing that is Vedia Barnett, a disabled vet who has received VA care for 25 years, including rehabilitation from a major stroke. As she told readers of Time earlier this year:

“I am not just concerned for myself — I am terrified for our senior veterans, those with severe combat injuries, survivors of military sexual trauma (MST), and those battling PTSD. They will all bear the brunt of this cruel decision… leaving our most vulnerable without the care they desperately need and deserve.”

May-June 2025, ATC 236