Against the Current No. 236, May/June 2025

-

Lessons of Abductions and Terror

— The Editors -

Vets Mobilize vs. DOGE

— Steve Early & Suzanne Gordon -

Upholding Reproductive Rights in Ohio & Beyond

— Marlaina A. Leppert-Miller -

The Humanities After Gaza

— Cynthia G. Franklin -

On Social Movement Media: Learning from Krupskaya & Lenin

— Promise Li -

The Rule, Not the Exception: Sexual Assault on Campus

— M. Colleen McDaniel & Andrew Wright -

Diktats, DOGEs, Dissent & Democrats in Disarray in the Era of Trump

— Kim Moody -

A Setback for Auto Workers' Solidarity

— Dianne Feeley - Columbia Jewish Students for Mahmoud Khalil

-

Plague-Pusher Politics

— Sam Friedman - Guatemala Human Rights Update

- A Remembrance

-

Fredric Jameson's Innovative Marxism

— Michael Principe - Reviews

-

The New Nuke Revival

— Cliff Conner -

Power in the Darkness

— Owólabi Aboyade -

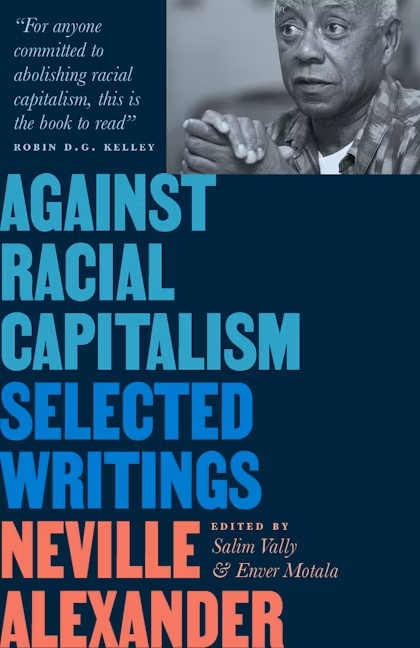

Racial Capitalism Dissected

— James Kilgore -

An Important Critique of Zionism

— Samuel Farber -

What's Possible for the Left?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Behind the Immigration Crisis

— Folko Mueller

James Kilgore

Selected Writings of Neville Alexander

Edited by Salim Vally and Enver Motala

Pluto Press, London 2023, 320 pages. $31.95 paperback.

IN 1991 I moved from Harare, Zimbabwe to Johannesburg, South Africa. The move was occasioned by a job offer from Khanya College, which operated under the slogan “Education for Liberation.”

Like many radical educational initiatives of the day, Khanya was a brainchild of legendary socialist and former political prisoner Neville Alexander. Though the details of my experience are for another day, suffice to say that my time at Khanya transformed my understanding of socialism and popular education for life.

Though I only occasionally encountered Neville during my time at Khanya, his influence and imagination were everywhere. This self-described “non-dogmatic Marxist, Pan Africanist, and internationalist” has a considerable profile in South Africa, especially within the Left, but he deserves far greater international recognition as a revolutionary actor and thinker.

This volume will help widen his reputation. Against Racial Capitalism is a collection of his writings, edited by two of Alexander’s close South African comrades, Salim Vally and Enver Motala. It offers both a biographical sketch of his remarkable life and a wonderfully representative collection of his work.

The writings cover not only his theoretical interventions on racial capitalism, the language issue in South Africa and his critical analysis of the African National Congress (ANC) strategy of two-stage revolution. The volume also includes his op-eds as well as texts of his public talks and essays.

A Life for Liberation

Neville Alexander was born in Cradock in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa in 1936, the eldest of six children. Riding the waves of his brilliance and the support of anti-apartheid educators among the “coloured” (mixed race in apartheid jargon) population of the Cape, Neville carved out a path to success like few black students of the day.

He graduated from the University of Cape Town at age 19 in 1955, then won a fellowship to study in Germany at the University of Tübingen, where he completed a Ph.D. on German drama in 1957.

Upon his return to South Africa, Neville became an active member of the Non-European Unity Movement of South Africa, a socialist formation founded in 1943 that offered a left critique of and organizational alternative to the Soviet-aligned South African Communist Party and the ANC.

At the time when Nelson Mandela was joining with the ANC’s armed forces of Umkhonto we Sizwe, Alexander was moving down a parallel path among a subset of Unity Movement cadre under the name the Yu Chi Chan (guerrilla warfare) Club.

Like Mandela, Alexander’s foray into guerrilla warfare didn’t last long. He ended up serving 10 years on Robben Island. During his years on “The Island,” among many activities, Alexander worked closely with Mandela and other ANC-aligned prisoners to form the Society for the Rewriting of South African history. They offered classes to other prisoners and even to some of the guards. Alexander’s specialty was history, whereas Mandela taught the law.

Upon his release from prison in 1974, Alexander was placed on house arrest for five years. Despite his restrictions, he remained politically active. When the Soweto uprising took place in 1976 under the leadership of Steven Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement, Alexander saw an opportunity to forge a revolutionary left outside the Stalinist tradition of the ANC and the SACP. However, before such a unity could come to fruition, the South Africa Police murdered Biko.

Critique of ANC Politics

Once he completed his house arrest, Alexander delved into a range of political, educational and academic ventures. Nineteen seventy-nine saw the publication of One Azania, One Nation, which Alexander penned under the pseudonym No Sizwe.

The book was a harsh critique of the ANC in which he refuted the “propagation and proliferation of bogus nationalisms, the main purpose of which is to dissipate the force of the class struggle by deflecting it into channels that will nurture the dominant classes.” For Alexander, these “bogus” categories were apartheid-inspired distractions. For him, a liberated South Africa would unite the entire population under the name Azania. By contrast, the ANC’s analysis posited that the dissolution of apartheid would be a two-stage process in which a bourgeois revolution would bring in a democratically elected parliament, much like European nations, to be followed by a working-class-led state.

This was anathema to Alexander, and his critique of the two-stage schema of revolution would remain a point of ideological tension between Alexander and his followers and the ANC-led government until his death in 2012.

Apart from debating the national question, Alexander directed his political energy into two major organizing projects — the construction of the National Forum (NF) in 1983 and the building of the Workers Organization of South Africa (WOSA) in 1990.

The NF brought together over 200 liberation forces across the nation. The NF was the socialist left reply to the ANC-led United Democratic Front, which was founded in 1983 with more than 400 members.

Similarly, WOSA ran candidates in the country’s first democratic election under the Worker’s List Party in 1994 but pulled a mere 4000 votes and ended up with no members in parliament.

Education for Freedom

Apart from his political organizing, Alexander was a dedicated educationist. In 1979, he joined with several radical education activists to form the South African Council on Higher Education (SACHED), a multi-pronged nonprofit that offered a host of programs and courses that opened the doors of higher education to black students previously excluded due to apartheid restrictions.

SACHED followed a Freirean methodology in their programs and adopted Education for Liberation as their slogan. SACHED’s projects included community learning centers and academic initiatives like Khanya College, a bridging program to facilitate Black student entry into historically white universities.

In the field of education, Alexander will most likely be remembered for his contributions to politics and pedagogy of language. In a country with 11 official languages, Alexander viewed the continuation of language and ethnically based schools as a perpetuation of apartheid dynamics even under a democratically elected government. He constantly agitated for reshaping language policy under the umbrella of a national consciousness, rather than the racialized and ethnicized approach of apartheid education or the moderate reforms introduced by the ANC when it came to power in 1994.

But Alexander’s theoretical interventions went far beyond language. As the editors point out, Alexander constantly emphasized how nationhood “might be constructed against the long history of racist division and the entrenchment of its forms of consciousness.”

For Alexander this construction did not imply a negation of the existence of other forms of oppression. He constantly emphasized the “indivisibility of the multifaceted nature of oppressive and exploitative regimes.”

He never adopted the notion of non-racialism which was the hallmark of the ANC critique of apartheid, nor did he concur with their acceptance of granting political power to “traditional” leaders such as Zulu Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

Rather, Alexander, along with other groups that aligned with the Black Consciousness and/or Trotskyist positions, held that “we are of the view that we should operate as one united whole toward the attainment of an egalitarian society for the whole of Azania. Therefore, entrenchment of tribalistic, racialistic, or any form of sectional outlook is abhorred by us. We hate it and we seek to destroy it.”

Committed Internationalist

Finally it is important to note that Alexander, as an internationalist, applied radical concepts from the global socialist context to the South Africa reality. Alexander was a major elaborator of the notion of racial capitalism long before the concept gained widespread acceptance in South African circles.

Similarly, he built on the Unity Movement’s long-standing critique of race as a biological category to deconstruct the non-racialism of the ANC and advance the importance of an anti-racist stance.

As a socialist and a public intellectual, Alexander’s paradigm of liberation extended to aggressive opposition to neoliberalism, both in South Africa’s 1996 shift to the free market economic framework known as GEAR (Growth, Employment and Redistribution) and the ANC government’s moves toward globalization and structural adjustment driven by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

This volume does a wonderful job of capturing the breadth and depth of Alexander’s work and vision, one that should find a place in the archive of all those attempting to imagine and fight for socialist and abolitionist futures.

May-June 2025, ATC 236