Against the Current No. 236, May/June 2025

-

Lessons of Abductions and Terror

— The Editors -

Vets Mobilize vs. DOGE

— Steve Early & Suzanne Gordon -

Upholding Reproductive Rights in Ohio & Beyond

— Marlaina A. Leppert-Miller -

The Humanities After Gaza

— Cynthia G. Franklin -

On Social Movement Media: Learning from Krupskaya & Lenin

— Promise Li -

The Rule, Not the Exception: Sexual Assault on Campus

— M. Colleen McDaniel & Andrew Wright -

Diktats, DOGEs, Dissent & Democrats in Disarray in the Era of Trump

— Kim Moody -

A Setback for Auto Workers' Solidarity

— Dianne Feeley - Columbia Jewish Students for Mahmoud Khalil

-

Plague-Pusher Politics

— Sam Friedman - Guatemala Human Rights Update

- A Remembrance

-

Fredric Jameson's Innovative Marxism

— Michael Principe - Reviews

-

The New Nuke Revival

— Cliff Conner -

Power in the Darkness

— Owólabi Aboyade -

Racial Capitalism Dissected

— James Kilgore -

An Important Critique of Zionism

— Samuel Farber -

What's Possible for the Left?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Behind the Immigration Crisis

— Folko Mueller

Folko Mueller

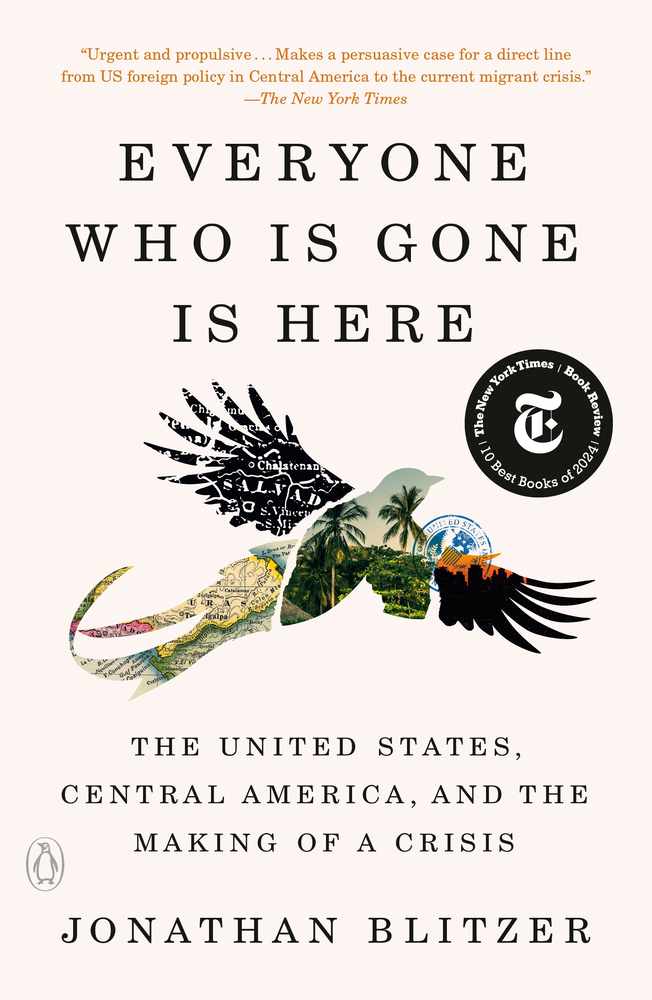

Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here:

The United States, Central America and the Making of a Crisis

By Jonathan Blitzer

Penguin Press, 2024. 544 pages. $21 paperback.

TYPICALLY MISSING IN the charges and counter-charges around the “border crisis” between the two mainstream parties is either empathy or any serious analysis of why nationals deemed “illegal immigrants” embark on the extremely risky journey to the United States.

How desperate does a person have to be to subject themselves and oftentimes their under-age offspring to the prospect of potentially getting robbed, raped or, in the worst-case scenario, even killed?

In Everyone who is Gone is Here, Jonathan Blitzer gives us a highly personalized account as to why. The book title refers to the people who leave their homes in Central America and cross the border into the United States.

In the 2024 presidential campaign, “illegal migration” and “border security” were constant themes. This was largely due to Donald Trump making this issue front and center. He developed a by now very familiar approach, sort of an anti-immigrant stump speech peppered with his typical lies and falsehoods as well as xenophobic and racist slurs.

These ran along the lines of: “The radical left” is opening our borders to welcome “stone-cold killers,” “monsters” and “vile animals” from countries cleaning out their “prisons and insane asylums,” which Trump repeated endlessly.(1)

It is well-documented that immigrants are less likely to commit crime than native-born Americans.1 These studies notwithstanding, the Democrat Kamala Harris in a noticeable rightward shift also started to deploy tougher rhetoric that culminated in the following statement on the evening of Sep. 27, 2024, after visiting the border in Douglas, Arizona:

“The United States is a sovereign nation, and I believe we had a duty to set rules at our border and to enforce them, and I take that responsibility very seriously.”(2)

Until 2023 the majority of migrants were nationals from Mexico and Central America, predominantly from the three countries that are collectively referred to as the Northern Triangle — El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. Studies by the Pew Research Center show that “Migration from Central America to the U.S. began rising notably in the 1980s,” and not surprisingly as Blitzer shows, “continued to increase in subsequent decades.”(3)

The Story of Juan Romagoza

Most of Jonathan Blitzer’s narrative evolves around the ordeals and adventures of Juan Romagoza, from Usulután, in the south-east of El Salvador. Juan’s story is representative of other tens or perhaps even hundreds of thousands of biographies of young Salvadorans coming of age just before and during the turmoil of the civil war, starting in the late seventies and lasting over a decade.

Growing up in a very pious household, Juan initially went and joined a seminary at the tender age of 13. Having witnessed sexual abuse there, he decided to not go back after half a year.

On the other hand, he had seen the effects of unattended medical issues in various family members, including his grandfather’s heart attack at age 52 from which he died before a doctor finally came three hours later.

This caused Juan to shift his entire focus to enter the medical field, and in 1970 he embarked on his medical studies at the University of El Salvador.

Throughout the 1970s El Salvador was rocked by repression, insurgency and increasing clashes between the army-backed business elites and workers who held protests and organized strikes. The university was also impacted and forced to at times close for months on end.

For Juan, this meant that his seven-year degree took 10 to complete. One of his last rotations before earning his degree was a surgery residency at a hospital in Santa Tecla, about 20 miles west of San Salvador. It was here that he made his first direct acquaintance with domestic state terror.

Although already an activist, who provided free healthcare together with other medical students to poor peasants who were forced to flee the countryside due to military repression, this incident must have undoubtedly politicized him a great deal further:

A badly wounded student protester who had taken police bullets to the neck and stomach was rushed to the emergency room on a gurney. Juan assisted in a four-hour surgery until the patient was stabilized and moved to the ICU. Here he remained at the student’s bedside together with a nurse, to monitor his vital signs.

Sometime after 10 pm a group of half a dozen men, some in army fatigues, some in plainclothes but all armed and masked in balaclavas abruptly entered the room, ordered Juan to get on the ground, and riddled the student with bullets.

After the men left, Juan picked up the spent bullet casings and carried them in his pocket for the remainder of the week. This was an extremely risky undertaking that could have cost his own life had he been randomly stopped and searched by cops, a routine occurrence in 1980s San Salvador.

The idea was to see Óscar Romero, the archbishop of San Salvador, to report this crime, so Romero could in turn record it with Socorro Jurídico, the human rights watch group associated with the church. There was simply nowhere else to turn to.

The Killing of Archbishop Romero

Juan had a previous history with Romero after the Archbishop’s close personal friend Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit priest who had been creating self-reliance groups among the poor, was assassinated on March 12, 1977.

Speaking of Fr. Grande, the previously conservative Archbishop Romero said, “When I looked at Rutilio lying there dead I thought, ‘If they have killed him for doing what he did, then I too have to walk the same path.”(4)

It was after this turn that Romero learned about the work that Juan and fellow medical students were doing. He asked them to become his “eyes and ears” so he could keep track of people who were tortured and killed and disseminate this information on his hugely popular weekly sermon broadcasts. This was crucial in a country where all news was censored.

A watershed moment for El Salvador was the killing of Archbishop Romero on the evening of March 24, 1980. “If they can get to Romero, no one can be saved.” Juan was told by his neighbor.

Indeed, the assassination meant that a “moderate” or negotiated solution was now out of the question and only a military solution remained viable. It was the kickoff for an unprecedent campaign of terror by the government, which included much higher levels of torture.

Juan was forced to do his job virtually underground and had to employ daily survival tactics, going to work in disguises and keeping odd hours at the clinic.

Nonetheless, he and his fellow activist medical students got wind of their names ending up on hit lists assembled by death squads and distributed among military officers. As an American official at the time pointed out: “If your name happens to be on the list and you are taken prisoner, your life expectancy is about one hour.”

In addition to helping other activists in the city who ended up injured after clashes with the police and other government forces at protests, Juan still made extremely dangerous trips to the countryside to help peasants who required medical attention and were trapped due to the ongoing battles between the military and leftist guerrillas.

Capture and Torture

During one of these missions, the military showed up in the middle of his medical exams and opened fire immediately, hitting Juan in his right ankle. Juan fell to the ground and was lucky that he did not get shot dead on the spot. The soldier who came over to shoot him point blank had forgotten to take the safety off and afterwards became distracted.

Juan was, however, taken prisoner on suspicion of being a guerrillero and hauled off to a military installation in Chalatenango, ironically called “El Paraíso.” It was here that he suffered tremendous atrocities. He was stripped down to his underwear, blindfolded and placed on a cement slab, where he would be interrogated for the next 24 hours.

Each denial of guerilla involvement would solicit a beating or shocks from electrodes. He was then transported to the capital San Salvador, where the torture methods grew far more intense. He was tied to iron rungs in such a position that his ankle wound would be further inflamed, sodomized with a metal rod and shocked.

The guards also put out cigarettes all over his body and would hang him by his fingers, wrists and legs until the wire cut down into his bones. One day, he was gratuitously shot in the left forearm, leaving it shattered. The torturer told him: “This is so that you will never practice medicine again.”

After being moved one last time, thinking he was going to get executed, the soldiers pushed him into a coffin where he was to stay for another 48 hours.

Eventually two of Juan’s uncles with ties to the military managed to get him released. However, Juan’s ordeal was far from over. Oftentimes the death squads would finish the job after a prisoner was released from military custody.

After moving from safe house to safe house for a couple of months, Juan’s ankle injury had become so badly infected that his only option left was to see a specialist in Mexico City for emergency treatment, or he would lose his foot.

A close family friend agreed to smuggle him out of the country into Mexico City, where he arrived in the spring of 1981. While the doctors were able to reconstruct Juan’s foot, the nerve damage in his forearm and hand was untreatable.

After recovering from his surgery, Juan came in touch with Sergio Méndez Arceo, the bishop of Cuernavaca, a city just about one-and-a-half hours south of Mexico City. After the bishop found out about Juan’s medical training, he invited him to help out with a medical clinic the church had set up for indigenous Guatemalan refugees.

Guatemala was also still in the throes of a civil war, which had been raging for decades and specifically targeted the Mayan population whom the Guatemalan military thought to be siding with the insurgent guerrilleros.

Crossing the Border

Méndez Arceo practiced liberation theology, using his seminary to train priests to serve the poor and combine bible study with local activism. He also established a network of fellow liberation theologists and activists to help the most vulnerable Guatemalan refugees cross into the United States, where they would be out of reach of death squads.

Juan routinely accompanied the different waves of refugees making the trip to the U.S. border, but was never tempted to cross himself. In Mexico he felt closer to his homeland of El Salvador. This changed when he found out through the Salvadoran expatriate community in Mexico City that his girlfriend Laura, who stayed behind, had been killed. Laura was a fellow activist from medical school days with whom he had a daughter. He hadn’t seen them in two years.

After hearing the news, he set out for the United States to try and set the story straight for ordinary U.S. citizens who did not know much about the reality of the civil war in El Salvador and hopefully initiate change that way. He was smuggled across the border and arrived in Los Angeles on May 5, 1983.

After three months he moved up to San Francisco where an aunt of his had been a long-time resident. Again his medical skills were in demand here, but he also assumed the role of a community organizer in a group he founded called Comité de Refugiados or CRECE, the Central American Refugee Committee and was active in the local sanctuary movement.

He soon gained some notoriety, speaking at church gatherings and to the press as well as leading sanctuary caravans into California. Articles started appearing around his work. When asked if he was scared being so active as an undocumented immigrant, he replied “Part of the therapy is shedding our fear.”

He also routinely appeared on panels with a pro-bono lawyer, Mark Silverman, who finally persuaded Juan to apply for asylum. Juan had never applied himself, since it was never his intention to stay in the United States. However, Silverman found the right angle when he told Juan his application could be a motivation for others to do the same.

Shortly after filing, Juan found himself on his way to Washington, DC with a group of other activists. There that he met Salvadorans from the same region as he was. They introduced him to a local community clinic that catered to immigrants called La Clínica del Pueblo. He was smitten by the place, as it was the sort of operation he always wanted to create in El Salvador.

Shortly after he was granted asylum, he got notice that “La Clínica” was on the verge of closing due to a lack of management and too much work for the existing volunteers. When asked if he would be willing to help and run it, he moved to Washington in the summer of 1987.

In 2002, Juan participated in a landmark trial against two men responsible for the worst suffering of his life: José Guillermo García, El Salvador’s minister of defense from 1979 to 1983, and Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, one of Juan’s interrogators back in 1980.

The lawsuit was filed by the Center for Justice and Accountability, a human rights organization in San Franciso, and one of their attorneys deemed Juan the perfect plaintiff. The idea was to seek redress on behalf of torture victims and since this was a civil, not criminal trial, the perpetrators would have to pay damages if found guilty.

The jury sided with the plaintiffs and the generals were ordered to pay $54 million in damages. However, for the plaintiffs it was never about the money.

In March of 2008, Juan returned back to his family home in Usulatán to live with his 82-year-old mother. After recovering from colon cancer, he occupied himself the only way he knew how — activism and practicing medicine.

From late 2008 to early 2009, Juan volunteered for the Mauricio Funes campaign, a FMLN candidate who was challenging the right-wing ARENA party. One of the central planks of FMLN’s platform was reforming the health-care system.

When Fuentes won in March of 2009, the administration started to roll out a network of clinics that would provide immediate primary care, free of charge. Juan ended up overseeing the 34 clinics in the department of Usulatán.

Cold War Logic and U.S. Interventions

Blitzer deftly interweaves Juan’s anchor story with insights from several U.S. administrations and their handling of the increasing violence in El Salvador, cross-border solidarity efforts by U.S. activists along the U.S.,-Mexican border; and the explosion of Latino gang warfare in the late 1980s and early ’90s.

This was to a large degree due to the rapid growth of the Mara Salvatrucha, predominantly composed of Salvadoran youth exiles in Los Angeles, a street gang that morphed into organized crime and is better known as MS-13. The growth of MS-13 can be directly traced to the Salvadoran civil war.

Older readers will remember the turbulent 1980s, which saw the United States engaging in wars around the globe fueled by Cold War logic. Particular attention was always reserved for what it still considers “its backyard” — Central America.

From the very beginning, this meant unequivocally supporting any right-wing government, no matter how brutal, against any political candidate or movement that displayed even a hint of sympathy for progressive or social justice policies. We can see this pattern with the U.S.-backed removal of Jacobo Arbenz, the democratically elected president of Guatemala in the early 1950s.

Arbenz won the presidential election primarily due to the promise of an agrarian reform. Once in office he followed through on this promise and passed the agrarian land reform bill after about a year in power.

The bill entailed nationalization of a relatively small percentage of unused agrarian land, a very popular move with most Guatemalans since land ownership continued be highly concentrated in the hands of a wealthy few. However, it drew the ire of the United Fruit company, the largest landowner in Guatemala and with a high percentage of unused agrarian land that it retained for its business of shipping bananas.

United Fruit started to heavily lobby the U.S. government into toppling the Arbenz regime. These lobbying efforts, coupled with general anti-communist hysteria among the U.S. administration, paid off and led to the U.S.-sponsored coup d’etat in the Summer of 1954.(5) This set in motion a four-decade genocidal military targeting of Guatemala’s largely Indigenous peasant population, claiming at least 100,000 lives.

The latest but most likely not last U.S. intervention to force an alternate political outcome in a Central American country happened in 2009 in Honduras when President Manuel Zelaya was forcibly removed from office. Elected as the candidate for the mainstream Liberal Party, he first started raising eyebrows when he joined the “Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas” or ALBA, as it is known in its Spanish acronym.

ALBA was initially a bilateral agreement between Cuba and Venezuela signed in 2004 and envisioned as an alternative to neoliberal policies, particularly the U.S.-backed Free Trade Area of the Americas (or FTAA), which ultimately failed to take off.(6)

The death knell was what when Zelaya was seeking a constitutional amendment. “Zelaya’s proposal to hold a referendum on a proposed new constitution was judged ‘illegal’ by congress, and the army was ‘invited’ to intervene by the supreme court.”(7) The coup was welcomed by then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

The result was the return of Honduras to death squad and drug cartel rule under president Juan Orlando Hernandez, who along with his brother are now serving life sentences after extradition to the United States for drug trafficking. The current Honduran administration of president Xiomara Castro faces the task of recovery from the disaster.

Against Amnesia

In his introduction, Blitzer states that “Politics is a form of selective amnesia. The people who survive are our only insurance against forgetting.” He has done a fantastic job capturing the account of one survivor, Juan Romagoza, and putting it in a broader geopolitical context of human beings fleeing from countries destroyed by the United States’ imperial actions.

Younger readers, who may not have witnessed firsthand Cold War politics and the zero-sum fear that drove it, should find this book particularly insightful, since it traces back some of the root causes of a 40-year migratory trek from the “Northern Triangle.”

The response from U.S. politicians, by and large and across the aisle, has been to “secure the borders of our nation” against the immigrant influx. Yet in human history, the creation of nation states as we know them is a relatively recent phenomenon of the past few centuries.

Fast forward to the age of the Anthropocene in which one species, our own, is destroying its own habitat, planet Earth, and we can quickly see how the notion of defending the interests and borders of one particular nation state against another seems not only antiquated and inadequate but may ultimately become obsolete.

The climate crisis doesn’t know national borders. But further, it exacerbates the already existing problems in the Global South, and fuels further migration. Only a concerted transnational effort based on solidarity with emerging countries, and taking the needs and concerns of the global working majority into account, has any chance of stemming the tide.

Notes

- Immigrants less likely to commit crimes than U.S.-born, NPR, “All Things Considered,” March 8, 2024.

back to text - https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/kamala-harris-tough-migration-pitch-border-points-shifting-national-mo-rcna172850

back to text - https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/ 2017/12/07/recent-trends-in-northern-triangle-immigration/#:~:text=Migration%20from%20Central%20America%20to,25%25%20between%202007%20and%202015

back to text - Archbishop Oscar Romero Beatified in El Salvador\Jesuits.org

back to text - Blum, William. Killing Hope (The Updated Edition). Monroe, Maine. Common Courage Press. 2004.

back to text - “ALBA: Creating a Regional Alternative to Neo-liberalism?” MR Online, February 7, 2008.

back to text - “Honduras: Back to the bad old days?” by Richard Gott, The Guardian, June 29, 2004.

back to text

May-June 2025, ATC 235