Against the Current No. 233, November/December 2024

-

Election and Widening War

— The Editors -

Beyond Reality: On a Century of Surrealism

— Alexander Billet -

Harris, Trump, or Neither? Arab & Muslim Voters’ Anger Grows

— Malik Miah -

Discussing the Climate Crisis: Dubious Notions & False Paths

— Michael Löwy -

Repression of Russian Left Activists

— Ivan Petrov -

Political Zombies: Devouring the Chinese People

— Lok Mui Lok -

Nicaragua Today: "Purgers, Corruption, & Servility to Putin"

— Dora María Téllez -

Labour's "Loveless Landslide": The 2024 British Elections

— Kim Moody -

Chicano, Angeleno and Trotskyist -- A Lifetime of Militancy

— Alvaro Maldonado interviewed by Promise Li -

Joe Sacco: Comics for Palestine

— Hank Kennedy - Essay on Labor Organizing

-

The UAW and Southern Organizing: An Historical Perspective

— Joseph van der Naald & Michael Goldfield - Reviews

-

On the Boundary of Genocide: A Film and Its Controversies

— Frann Michel -

Queering China in a Chinese World

— Peter Drucker -

Abolition, Ethnic Cleansing, or Both? Antinomies of the U.S. Founders

— Joel Wendland-Liu -

Emancipation from Racism

— Giselle Gerolami -

The Labor of Health Care

— Ted McTaggart -

In Pristine or Troubled Waters?

— Steve Wattenmaker - In Memoriam

-

Ellen Spence Poteet, 1960-2024

— Alan Wald

Giselle Gerolami

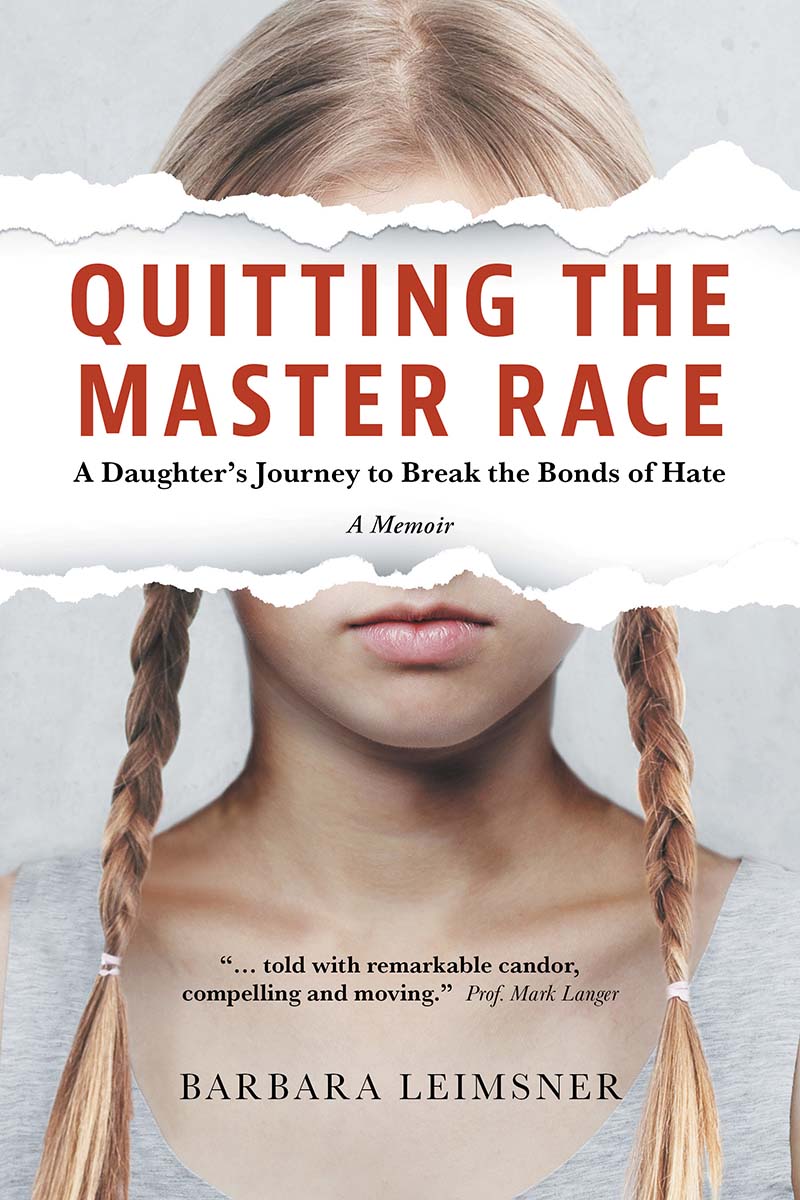

Quitting the Master Race:

A Daughter’s Journey to Break the Bonds of Hate

By Barbara Leimsner

Friesen Press, 2024, 240 pages. $12 paperback.

QUITTING THE MASTER Race is a memoir in which the author grapples with the legacy of her father’s Nazi past. I knew the author in the 1990s, when we worked together on several campaigns incuding one to get an abortion clinic set up in Ottawa. I was only vaguely aware of her parents’ story so I was very interested to hear her account when the book came out.

Barbara Leimsner’s family came to Canada from Germany in 1957 when she was almost four years old. They settled first in Oshawa, Ontario and later in Whitby, Ontario, drawn by jobs in the auto industry. Unlike many German immigrants, her father was unrepentant about his affinity for the Nazi regime and tried to instill his racist, antisemitic views in his two daughters.

The book is divided into two parts. The first covers the author’s life with her father from her childhood memories up to his death. The second is her journey, starting in 2014, to visit and study the places where he lived in order to understand how he could have become so thoroughly indoctrinated in Nazi ideology.

As a child, the author accepted what her father said without question. Neighbors and other members of their community were categorized according to a hierarchy in which Aryans like their family were at the top and everyone else was somewhere below. Certain facial characteristics and dark hair or skin were signs of low intelligence and inferiority.

Although prone to flashes of anger, her father was a good-natured, loving and attentive parent and she loved and looked up to her “papa.” Their household was a traditional one where German was spoken and Canadian junk food eschewed.

Her father raised pigeons and occasionally other livestock in their yard and believed in living off the land. Her parents were frugal and hard-working but struggled to get ahead with their limited English skills.

As she grew older and started to understand that not everyone thought like her father, she struggled with the disconnect. She watched “The Sound of Music,” began hearing about how six million Jews were killed in the Holocaust, and was confused about why everyone was mourning the assassination of John F. Kennedy while her father celebrated.

He burned her comics and later destroyed her sister’s Jim Morrison records, acts that were reminiscent of Hitler’s book burnings.

She began to reject her father’s ideas as she was swept up in the radicalism of the movements of the late 1960s and early ’70s. After two summers working and traveling in Germany, she was accepted in the journalism program at Carleton University in Ottawa where she encountered a diverse study body, was exposed to new ideas by Marxist professors, and became involved in student activism.

After she and her sister had moved out and established their own lives, her father began treating her mother with cruelty. The cruelty intensified after her mother developed acromegaly that enlarged her hands and feet and distorted her facial features, and this continued until her death from cancer in 1993.

Late in life, her father appeared to have mellowed or changed. He joined the New Democratic Party — Canada’s left of center, labor party — even though he couldn’t vote. He began dating a Haitian woman and she remained his companion until his death from cancer in the spring of 2003.

Seeking Understanding

For over a decade after her father died, Barbara buried her complicated emotions about him. In 2014, after she and her partner retired, she decided to visit her father’s birthplace to try to gain an understanding of what had made him the man that he was.

In 2018, she began her trip to Germany and Czechia with a visit to her Aunt Jutta, her father’s youngest sister. Her aunt recounted how three million Germans were expelled from the Sudetenland in 1946, in retaliation for German atrocities under the Nazis.

The family had been living in their ancestral home, Freidland, which became Bridlicna. They were given 24 hours to leave and were allowed to bring very little. When they arrived in Germany, they were treated poorly. Interestingly enough, her aunt seemed to harbor little bitterness over the expulsion.

The author is very clear that as traumatic as this must have been, expelled Germans for the most part went on to live full and meaningful lives — unlike Jews and others who suffered horrible deaths in concentration camps.

The author visited Prague before making her way to Bridlicna where she got to see the house where her father was born, the house the family lived in when they were expelled, and the church where her father was baptized. She saw the area where her father gathered mushrooms, fished for trout and spent countless hours birdwatching.

After the defeat of Germany in 1918, the Czechification of the Sudetenland caused resentment among the German population. Economic hard times after 1929 increased that resentment. The author’s father along with other young men from Freidland left to join the German army in 1938 rather than being conscripted by the Czech army.

The Munich Agreement gave Hitler control of the Sudetenland. In the December 1938 elections, 97% supported the Nazi Party, making it the most pro-Nazi region.

Her father served seven years in the German army, first in the Balkans but later in Crete, which was occupied by the Germans from May 1941 until October 1944. Her father revealed very little about his time in the army. She has 21 black-and-white photos of his time in Crete, most of which do not show the war.

The author is left to guess, based on the history of this time, what her father’s work may have been. It is known that guerilla resistance was met with extreme force that turned into an “orgy of violence” against the citizens of Crete by August 1944.

There was a mythology in Germany after the war that the ordinary German soldier played no part in atrocities. According to Leimsner the reality was quite different. “Though originally separate from the Nazi movement, the German army became a vital arm of its terror regime and was deeply implicated in its criminal and genocidal policies.” (190)

Her father spent time in a Russian prisoner of war camp before leaving Crete, possibly escaping, and returning to his hometown shortly before the expulsion. Rather than confront the truth about Nazism after the war, he wrapped himself tightly in its ideology. The author wondered if it might have been different had her father stayed in Germany, where his generation underwent a process of reckoning with this ugly period of history.

Finding Compassion

When the author visited her sister Marianne a year after her trip, the two sorted through bins of old papers and family memorabilia. They discovered that their mother had worked for Organisation Todt, a construction company that administered the concentration camps from 1943-1945. She wondered if her mother even thought about the people behind the cataloging as she worked away at her typewriter. But their mother had never glorified the Nazis in the way her father had.

After years of feeling horror, anger and shame about her father’s past and through her journey to know and understand him better, the author was able to recover “what was good in my father” and to view him with compassion.

While not absolving him, she draws an important lesson for today: In times of economic crisis, ordinary people much like her father are being drawn in by the same simplistic answers, scapegoating and hatred as he was.

“Although conditions are not the same today as they were in the 1920’s and 1930’s, the multilayered, unpredictable economic, political and ecological crises that we face are creating ideal conditions for the far right to grow again — to an even greater extent than in my father’s day.” (205).

We are seeing the rise of the far right in Italy, France, Germany and India. In the United States, Trump has blamed immigrants and people of color for the hardships faced by the supposedly “hardworking” Americans.

But a replay of Nazi Germany is not inevitable. The author believes that it is important not to remain silent when faced with racist hatred. She sees hope in the movements like Black Lives Matter, youth movements to address the climate crisis, and the recognition in Canada of the brutal legacy of residential schools for Indigenous children.

Unfortunately Barbara Leimsner was not able to discover more specifics about her father’s experience and had to rely fairly heavily on the historical record. It is unclear to what extent that was a disappointment to the author, but one can imagine that it must have been. Certainly Barbara Leimsner’s account opens a window onto the broader issue of white supremacy and how it can be overcome.

Learning About White Supremacists

From people who have been drawn in and subsequently rejected white supremacy and from those who have studied this phenomenon, there are characteristics of those who embrace hate as an answer to society’s problems. They are looking for belonging or acceptance. They are angry over an injustice, real or perceived. They are experiencing personal or financial struggles.

Extremists target people that fall into these categories because they can more easily be manipulated into believing that another group is at fault for their problems.

Life After Hate is a project that works with former white supremacists to help them disengage from hate groups. Arguing with white supremacists is counterproductive and simply furthers their sense that the world is against them. Only once shown compassion and understanding are they able to see humanity in others. Mentoring from other former white supremacists and various forms of counseling have proven effective.

Christian Picciolini, a former racist skinhead and member of Life After Hate and other disengagement projects, says the following in response to what parents can do to prevent their children from being drawn to extremist hate groups:

“And certainly because I am a former extremist, I have a certain credibility talking with people who are still extremists, but I think all parents, all psychologists, all teachers, can do what I do. It really is just identifying vulnerable young people and then amplifying their passions [and] trying to fill those voids in their life, because I’ve never met a happy white supremacist. I’ve never met one with positive self-esteem. Everybody in these movements are there because they are broken to a certain degree and they’re looking to project their pain onto somebody else. And I just see my job as kind of a bridge builder to the services that they need, and that’s not making excuses for them. I still hold people accountable in many of the same ways I’ve held myself accountable for 23 years.” (NPR, “Here and Now,” August 9, 2019)

The extent to which the author’s father might fit into the profile described above remains opaque. Is it different when an entire society is swept up in a hateful ideology?

Without the author’s unability to locate the exact turning points in her father’s life, nevertheless Leimsner has woven a fascinating and accessible story. Quitting the Master Race is a book with a powerful message, particularly at this moment in time. It’s no surprise that it is being read in book clubs all over the United States and Canada.

November-December 2024, ATC 233