Against the Current No. 233, November/December 2024

-

Election and Widening War

— The Editors -

Beyond Reality: On a Century of Surrealism

— Alexander Billet -

Harris, Trump, or Neither? Arab & Muslim Voters’ Anger Grows

— Malik Miah -

Discussing the Climate Crisis: Dubious Notions & False Paths

— Michael Löwy -

Repression of Russian Left Activists

— Ivan Petrov -

Political Zombies: Devouring the Chinese People

— Lok Mui Lok -

Nicaragua Today: "Purgers, Corruption, & Servility to Putin"

— Dora María Téllez -

Labour's "Loveless Landslide": The 2024 British Elections

— Kim Moody -

Chicano, Angeleno and Trotskyist -- A Lifetime of Militancy

— Alvaro Maldonado interviewed by Promise Li -

Joe Sacco: Comics for Palestine

— Hank Kennedy - Essay on Labor Organizing

-

The UAW and Southern Organizing: An Historical Perspective

— Joseph van der Naald & Michael Goldfield - Reviews

-

On the Boundary of Genocide: A Film and Its Controversies

— Frann Michel -

Queering China in a Chinese World

— Peter Drucker -

Abolition, Ethnic Cleansing, or Both? Antinomies of the U.S. Founders

— Joel Wendland-Liu -

Emancipation from Racism

— Giselle Gerolami -

The Labor of Health Care

— Ted McTaggart -

In Pristine or Troubled Waters?

— Steve Wattenmaker - In Memoriam

-

Ellen Spence Poteet, 1960-2024

— Alan Wald

Alvaro Maldonado interviewed by Promise Li

AGAINST THE CURRENT editor Promise Li: I met Alvaro Maldonado as a college student, at Gabe Gabrielsky’s apartment in Los Angeles during a Solidarity branch meeting.(1) Years later, I encountered Alvaro again at a Palestine solidarity rally and learned more about his lifetime contributions to Latino, labor and antiwar movements. Alvaro was at the center of major LA mass movements ever since the Vietnam War, from witnessing the rise of Chicano politics as a high school student to helping to coordinate the largest-ever protests for immigrant justice in LA history.

The LA immigrant justice movement was a light in the darkness of the 1990s and 2000s, which oversaw a historic low point of the socialist left. Alvaro’s perspectives provide a distinctive glimpse into this history because they give a first-hand account of how the political divisions between Latino moderates and radicals shaped crucial moments in LA politics.

Many of those who organized alongside Alvaro during the mass mobilizations against the anti-immigrant Proposition 187 in 1994 — a ballot initiative that denied social services to undocumented immigrants — have become a new generation of Latino liberals that have since taken the helm of the Democratic Party in LA.(2)

Alvaro represents a different path: an unyielding undercurrent of Chicano militancy that fights for political independence and self-emancipation of the working class. These perspectives draw from his commitment to revolutionary socialist and Trotskyist principles, cultivated in his time in organizations like Socialist Union, Solidarity, and the International Socialist Organization (ISO).(3)

Alvaro and I are now members of the LA branch of Tempest Collective, and Alvaro continues to be active in the anti-war movement, recently helping to form Anti-US and Israeli Imperialism in the Middle East (AUSIIME), a new South Pasadena-based antiwar collective.

These political nuances are under-explored in accounts of LA history in this period. Alvaro’s role receives only cursory mentions in scholarly histories like Rodolfo Acuña’s Anything But Mexican (1997) and Chris Zepeta-Millán’s Latino Mass Mobilization (2017). But understanding these differences in politics and strategy is precisely what we need in the LA left, where immigrant Latino workers continue to be the militant backbone of LA politics, and new generations of Democratic Party politicians continue to contain the militancy of Angeleno working-class struggles.

The most extensive treatment of Alvaro’s role in these movements lies in Jesse Diaz’s 2010 dissertation, Organizing The Brown Tide. This interview builds on the invaluable history first recorded in Diaz’s work.

Promise Li: Can you tell me more about your background and how it influenced you to be involved in community work?

Alvaro Maldonado: I was born in 1952. My grandparents migrated to the United States from the northern Mexican states like Sonora and Chihuahua, part of an early wave of Mexican laborers who worked in the fields and cities. They lived and moved around the Southwest, and my parents ended up in the barrios of Boyle Heights in East Los Angeles, where I grew up.

At the time, there were a lot of social problems in East LA that affected the Chicano community, especially the youth: high dropout rates, overcrowded apartments, poverty, and not many recreational programs for the community. My high school, Roosevelt High, had the second-largest dropout rate in the city — nearly half of the students were dropping out.

Everyone shared feelings of dissatisfaction and demoralization. Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” did introduce some social programs, though I later realized it was an anti-communist response to militant organizing in our communities and something to distract us from the imperialist war in Vietnam. But even these programs were being defunded by the time I became a teenager, and Black and Brown communities were forced to compete over scarce resources in LA’s poor areas.

Like many other Chicano activists of my generation, I was first exposed to community work through the Community Service Organization (CSO), a Mexican American civic organization. I participated in CSO’s teen leadership summer program where we were asked to come up with a community project, and I suggested organizing a boycott campaign against a local grocery store to pressure them to lower food prices so people in the barrios can afford fresh produce.

That was my first experience in organizing.

The Historic “Blowouts”

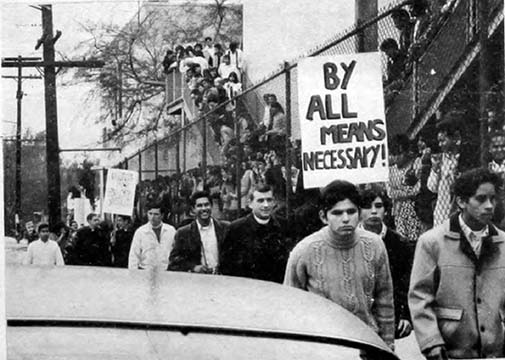

When I was in my sophomore year of high school in 1968, the first wave of “the Blowouts” were beginning: The second wave, in 1970, when I was a senior, was even bigger: tens of thousands of students walked out of classes to protest racism against minority communities, demanding more resources for Chicano students, like bilingual and bi-cultural education, and expanding basic facilities on campuses.

It was one of the earliest mass movements that united and mobilized the Mexican-American community. The movement quickly raised my political consciousness, and I participated in the walkouts at Roosevelt, where over a third of the students walked out. I also saw other minorities participating, from Japanese to Black students.

I joined United Mexican American Students (UMAS), one of the leading groups in the walkouts, and was elected as a representative in my school’s assembly body. We demanded more Latino teachers, more affordable lunch options, and Chicano cultural programming. Our UMAS chapter joined other ones to become a Chicano nationalist organization, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), shortly after the Blowouts.

PL: The Blowouts occurred around the same time as many major mobilizations. How did you and other Chicano youth militants in East LA connect to these broader movements?

AM: After the Blowouts, I wanted to get more involved in organizations, and joined a grassroots Chicano activist magazine and collective called La Raza, which played a key role in documenting the walkouts.

The Vietnam War was ongoing at the time, and members of La Raza helped to form the Chicano Moratorium to organize a broad coalition of Chicano activists toward anti-war work. I led the Moratorium’s outreach committee, flyering and educating our neighborhoods about the war, and spoke at local actions.

We also helped gather solidarity support for the Delano grape strike boycott in LA that had been going on for a couple of years already, and I got to support the strikers in person during a family trip up near Delano. I was fortunate to meet strike organizer Larry Itliong at his office, who directed me to participate in the pickets at Giumurra Vinyards in Arvin (the biggest picket in the strike) and other strike solidarity work during the final week of the strike, and witness the victory.

There was a lot going on at the time, and there were many overlaps between organizations and campaigns. The Chicano Moratorium’s highlight was a large rally in East LA on August 29, 1970 that drew over 30,000 protestors and was the biggest action organized by any single ethnic group in the United States at the time.

That rally was also my first time witnessing this scale of police brutality. LAPD dropped tear gas from helicopters, injuring dozens of people, setting buildings on fire, and a couple of people were murdered — some Brown Berets and LA Times journalist Rubén Salazar. Salazar was the first Chicano journalist in a mainstream news outlet to report on Chicano community issues, and we held demonstrations following the rally to demand justice for him.

La Raza members began thinking more seriously about local politics, and we helped organize the East LA branch of La Raza Unida Party. This turn to party politics resulted from our increasing dissatisfaction with Democratic Party politicians, and the desire to have an organ for independent mass politics for Chicanos. Though I was still a nationalist and was not a socialist yet, my experience in the party was what first led me to understand the value of independent politics outside of the two-party system.

We helped run a campaign for Raul Ruíz, one of the key leaders of La Raza who helped advise students during the Blowouts, for state assembly twice. Though we did not succeed, we garnered enough support among working-class Chicanos that the Democratic Party candidate whom Ruíz ran against (who was a Chicano liberal) lost to a Republican for the first time.

Turning to Socialism

PL: How did your experience in Chicano movements prepare you for entering revolutionary socialist politics?

AM: Different left organizations were present in La Raza Unida Party, hoping to shape it. I was particularly impressed by some Chicano socialists I met in the party, like Jesus Mena and Alejandro Ahumado, who told me they were also members of the Socialist Union. I watched how they raised issues, how they were firm on their principles, and how to argue them.

They were often in the opposition but also helped to build the party. Though my politics were not always clear then, and I was naive still, they also noticed that I was critical too and did not go for every bit of bullshit coming from the leaders. They eventually recruited me into Socialist Union meetings, where I met my first mentors in the socialist movement, Gene Warren and Milt Zaslow.(4)

I didn’t consider myself a socialist until I met people in Socialist Union like Jesus, Gene and Milt. Milt was our main mentor, an older Trotskyist who first split from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the 1950s. He was the one who taught us basic Marxist principles, clearly explaining how different issues and movements fit together. We would go to his house for political education and have study groups on topics like the Paris Commune.

Gene knew how to get to the core of the issue and broke things down clearly for us — in layperson’s terms. He was key in identifying sites of struggle across the movements. Jesus was our main link to the Chicano movement through La Raza Unida Party.

Socialist Union had members in fractions organizing in different areas of work, like solidarity with Black communities against police violence and antiwar work. I became part of the Chicano fraction with Jesus and others, active in groups like the Moratorium and La Raza Unida Party.

One key debate that emerged in La Raza collective at the time that eventually made me leave and commit my time to Socialist Union and its other fractions was whether to build closer relations with the then-president of Mexico, Luis Echeverría. Echeverría was repressing many workers and socialists, and was responsible for the massacre of the student activists at Tlatelolco as interior minister in 1968. But he was also starting to offer financial support to many Chicanos and Chicano organizations abroad.

The Socialist Union comrades and I were the key ones in the East LA La Raza collective meetings to oppose closer ties with Echeverría’s government. We believed that we should not be providing left cover for an administration that was actively oppressing the proletariat, our comrades, and the masses in Mexico.

Jesus, Alejandro and a few other dissenters were finally expelled in a collective meeting I missed. I attended the following meeting to raise the issue again and defend their positions, but I was also dismissed. As movements began to wane in the 1970s, the collective soon fell apart, as the Democrats were co-opting more and more Chicano organizations.

PL: Can you say more about why Socialist Union’s politics and organization appealed to you?

AM: Socialist Union brought me to the Trotskyist tradition, which I still identify with. I found its emphasis on workers’ democracy valuable, which means the working class must control the government, and that independent unions are needed — even in a workers’ state. It gave me a framework to critically understand the setbacks and contradictions of the Soviet Union, and why it made the mistakes it did.

Also, we were embedded in broader movements through our fractions, maintained our principles, and did the work with others in the larger left in a non-sectarian way, even though they did not always treat us very well. Of course, their emphasis on building the Chicano movement drew me in.

I wasn’t around yet when Gene and other Socialist Union members, as founding members of Friends of the Panthers, helped Geronimo Pratt and other Black Panthers defend against LAPD’s hours-long assault in the Panthers’ LA headquarters. Gene’s advice to quickly bulletproof the headquarters with telephone books probably helped save many people’s lives that day. These stories showed me that these people were not playing around. They were dedicated, brilliant, and sincere.

By the time I joined, we continued our work with Black movements with other former Panthers like Michael Zinzun, who helped organize early efforts to call out police brutality in South Central and Pasadena. A few others and I from Socialist Union drove down to South Central for meetings to help build Zinzun’s Coalition Against Police Abuse (CAPA).

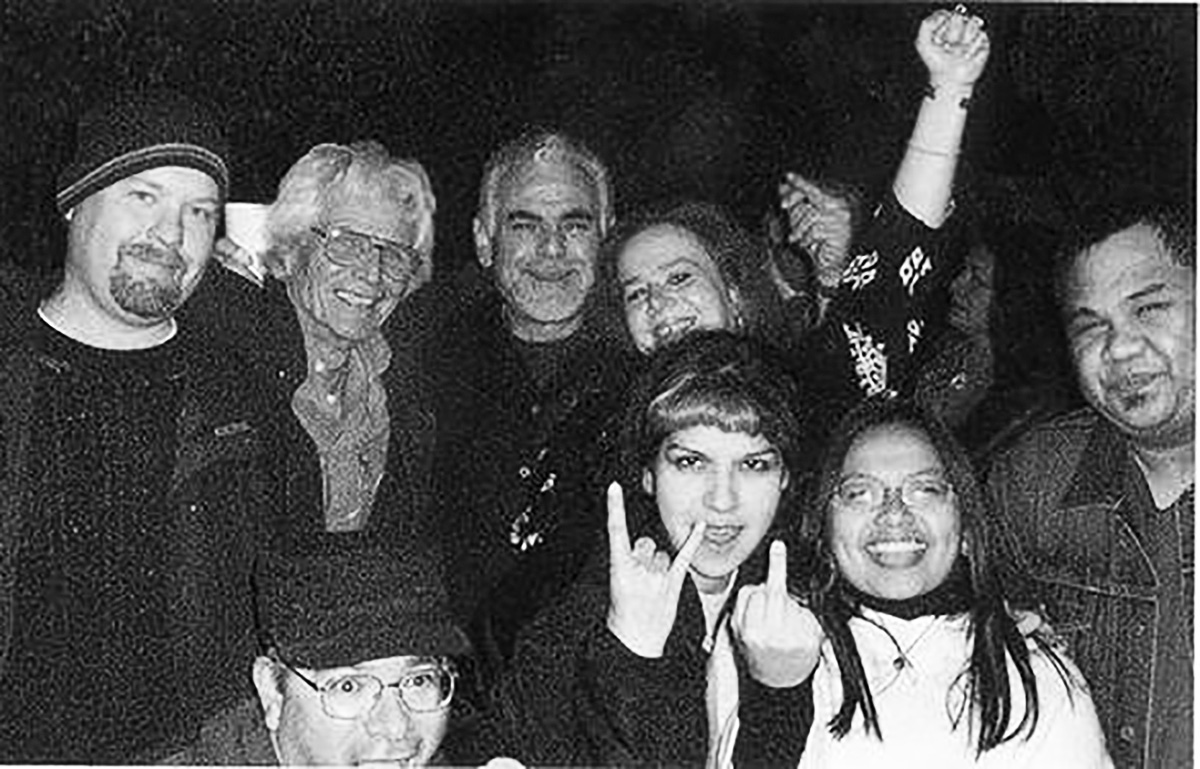

Socialist Union was never too big, but we had a generally healthy dynamic. On good days, there were around 40 people in the LA branch meetings. There was good discussion and analysis, just as we all organized in different fractions. We would recruit by twos and threes through this fractional work (which was how I was brought in). Mike Davis also attended our branch meetings in the 1970s, and I had the privilege of knowing and driving him around to rallies and meetings at the time. He later joined Socialist Union as well.

Movement Decline and Revival

PL: What happened throughout the rest of the 1970s and ‘80s for you as movements began to ebb?

AM: Well, I enrolled in Cal State LA after I graduated from high school and enrolled in a remedial program in 1970, but by then I was mostly caught up in politics and found the professors rather elitist and the learning environment difficult. So I dropped out pretty early, and worked as a groundskeeper for LA County until the mid-1980s.

I was in SEIU Local 660, and a member of the bargaining committee and also a shop steward, when I witnessed the union leadership sideline us rank-and-file members during our contract negotiations. I also had my own family in the 1970s, and got increasingly burnt out balancing between family and politics, especially upon my brother’s death.

I was out of politics for most of the 1980s as I tried to spend more time with my family, and returned to college at East LA Community College to finish my degree. Then I started working as a driver for the Japanese consulate starting in 1986.

Gene called to invite me to a solidarity rally with the Tiananmen students who were being repressed in 1989, and I started coming back out to more community actions after that. Socialist Union didn’t exist anymore by that point, and Gene brought me to Solidarity. Solidarity was active in building a local coalition against the Gulf War, and organized general assembly meetings that had a couple hundred people.

I met Warren Montag in Solidarity meetings, and I often agreed with him politically. I motivated a stance in Solidarity that we should specify that our opposition to the war should not entail support for Saddam Hussein. Warren and John Barzman agreed. We brought that to the coalition, which also approved it, and included this caveat in our flyers.

I also did some solidarity work with Mexican workers. In the mid-70s, I joined other Socialist Union members to travel down to Tijuana upon invitation by our Mexican comrades to support striking teachers.

The climate was pretty repressive at the time, and we were warned that the police might use live rounds. I thought we were going to be killed! But we were safe and ended up participating in an impressive large march. We made other trips to support Mexican comrades, like in Baja California, and hosted some of them to speak in forums in LA.

In 1993 I helped organize a coalition with local groups like the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES), the LA Peace Center, and the National Lawyers Guild to support striking workers in Ford plants in Mexico.

We picketed some Ford dealerships and were in contact with some workers’ representatives in Mexico. We managed to pressure the manager to meet with us; he tried to persuade us to stop, but we threatened to escalate the pickets into boycotts across more dealerships. The workers won a week later, and one of the workers’ representatives in Mexico thanked us for our support. Internationalism with Mexican workers is a key organizing priority, especially for LA.

PL: Around this time in the 1990s, you were also one of the key people who launched the early organizing efforts that led to mass protests against a draconian anti-immigrant bill in California, Prop 187, in 1994. These protests were among the largest in California history. Can you tell us more about the proposition and your role in these mobilizations?

AM: In the early 1990s, there were growing anti-immigrant and anti-Latino sentiments, especially in LA. In late 1992 and early 1993, several terrible bills and proposals were coming from both parties, but especially the Democrats, that criminalized and made it harder for undocumented immigrants to live.

Prop 187 was the culmination of these racist measures: it would have required local police, school administrators, and workers in many different sectors to report suspected undocumented immigrants, while denying the right to healthcare and education to their children.

I was working at the Japanese consulate at that time, and I remember that the Japanese prime minister also publicly scapegoated Black, Puerto Rican, Mexican and other Latinos to deflect the anti-Japanese hysteria that was also happening then.

Though the widespread outrage against Prop 187 eventually turned out masses of people, there was initially little response from the liberals and all the major Latino and immigrant nonprofits. At most, a few groups were lobbying their representatives. And so the left could fill an important political vacuum.

Mobilizing for Immigrant Rights

Even before Prop 187, I began to reach out to other activists in 1993 to build a coalition to start organizing mass demonstrations to resist these attacks on immigrants. Don White from CISPES and the LA Peace Center was central in helping me gather activists for the first meeting.(5)

I was pretty dissatisfied working at the consulate after hearing the Japanese government’s comments, and as the coalition began to grow, I remember putting the consulate’s number down as the contact in the coalition’s calling cards. At one point, the operator complained that I was getting more calls than the rest of the consulate altogether!

I called a meeting with activist friends, ranging from other Trotskyist groups to groups like CISPES, who I think helped bring out immigrant organizations like Central American Resource Center (CARECEN) and El Rescate. We initially met at CARECEN’s office, though they soon pulled out, maybe under pressure since many of us opposed working with the Democratic Party. El Rescate was smaller but more militant and left-wing, and hosted our meetings.

We organized our first demonstration downtown and got hundreds to come, including the Chicano historian Rodolfo Acuña and then-president of UNITE HERE Local 11 Maria Elena Durazo. These kept growing, and our last one in MacArthur Park gathered more than a thousand — before Prop 187 was even on the ballot.

By 1994 things were moving faster, and mainstream immigrant organizations were feeling the pressure to respond. Someone invited the United Farm Workers to attend one of our meetings, and they stacked our meeting (with the help of SWP members) to successfully win a majority to cancel our next demonstration (which we had already been promoting for weeks) to instead join a rally they organized with larger groups at East LA College. They guaranteed that members of our coalition could speak, but I believe this ultimately contained the growth of our militant coalition, which lost momentum toward becoming a mass force.

Nonetheless, we maintained our coalition, called the Pro-Immigrant Mobilization Coalition, just as our representatives affiliated while helping to build the larger one. This larger coalition now contained the city’s biggest NGOs, politicians, and other mainline Latino and immigrant organizations.

This was where key Latino liberal politicians, many of whom would become the future of the Democratic Party, first rose to prominence, from Gil Cedillo to Fabian Nunez. The coalition discussed what must be done to stop Prop 187, and I emphasized that mass demonstrations on the streets are needed, not just lobbying politicians.

There were opportunist elements in this coalition from the start. I suggested at an early meeting that the coalition’s points of unity must also show solidarity with Haitian immigrants, many of whom were escaping after the United States overthrew Aristide’s regime and were being detained in Guantanamo. But this was rejected by the coalition leaders, headed by Juan Jose Gutierrez of One Stop Immigration, saying that Prop 187 was just about Latino issues.

More embarrassingly, a couple of delegates from Haitian immigrant organizations were present at the time; they left after that discussion and never came back. It was a missed opportunity to connect with the Black community.

Guttierez also proposed having “celebrity” immigrants speak at our upcoming rally to boost our cause — and suggested Henry Kissinger! Don White and I immediately spoke up to condemn this, listing out Kissinger’s imperialist atrocities, and they backed down, knowing that we would organize counter-protests at the meeting if this idea went through. Later in the movement, they began to exclude me, once changing the meeting location without informing me and some others.

Though some delegates were open to organizing demonstrations, the coalition was nonetheless hesitant to agitate directly against the Democrats. But our original, more militant coalition remained active, and we went after Latino and other Democratic lawmakers who were proposing “milder” anti-immigrant policies while posing as supporters of the emergent immigrant justice movement.

These were Democrats who called themselves “pro-labor,” but proposed measures that would sanction employers employing undocumented workers. We picketed in front of then-Assemblymember Richard Polanco and then-Senator Barbara Boxer’s offices, and within days they each dropped their proposals.

As the movement grew, I joined others in this larger coalition to attend a general assembly meeting at Sacramento with other anti-187 organizations across the state to discuss state-wide strategy. In one of the breakout groups, I argued that we need mass demonstrations across Californian cities against Prop 187, that only mass movements from below can stop this proposition. People were on board in the working group, but some opposed it in the general assembly, in fear of alienating voters. Some key Latino activists, including Cedillo and Nunez, supported me when I spoke about it back in the general assembly, though some of these individuals were trying to play the left while remaining close to the Democrats.

The general assembly ended up voting on this proposal, and a majority adopted it, committing to organize mass demonstrations when we all returned home, although not a single city actually ended up doing it except for us in LA.

Our first LA rally had 30,000 people, which already exceeded our expectations. We thought maybe a few thousand would come out. The second one was even bigger, and finally, the third one brought out in excess of 100,000 people, one of the largest rallies ever in LA at the time. Many other independent pickets, including massive student walkouts, were also happening outside the coalition at the time.

Though voters did pass Prop 187, we organized massive demonstrations at the district courts to rule it unconstitutional, and eventually won, and our opponents did not escalate the fight to the Supreme Court. I am convinced that this victory was won because of these mass mobilizations, because the establishment witnessed how Latino communities were radicalized and struggled for power.

The bourgeois parties did not want immigrant workers to keep mobilizing and joining unions and mass organizations. The victory against Prop 187 demonstrates the power of immigrant workers and the Democratic Party’s efforts to contain that.

Pro-immigration and Antiwar Organizing

PL: The momentum generated by the mass protests against Prop 187 had soon died down, and many leaders of the movement became the new generation of Democratic Party leaders that would shape LA city politics to the present day. But anti-immigrant policies and resistance against them continued, culminating in the largest single-day rally in LA history in 2006 against HR4437, the anti-immigrant bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives but which failed in the U.S. Senate. How did the immigrant justice movement develop during this time, and what was your role?

AM: There was a lull after Prop 187, but things started picking back up as the Iraq War started. In the early 2000s, I helped organize a local group called San Gabriel Valley Neighbors for Peace and Justice that held weekly vigils to protest the war and spread awareness. Hundreds of these vigils spread across the country at the time, and some led to mass demonstrations. Members of the ISO joined our vigil, and I became friends with some of them.

Around this time, militant anti-immigrant groups like the Minutemen Project and Save Our States (SOS) were forming and gaining traction, beginning in Arizona. While the two parties continued to push through anti-immigrant policies through legal means, these groups organized right-wing vigilante patrols to target and harass immigrants.

The ISO comrades got word that some of these groups were planning to shut down a day laborers’ center in Laguna Beach, and invited me to join them to defend the immigrant workers. So I joined the ISO comrades, alongside anarchists and other militants, to help. We had more than a hundred people, joined by a couple dozen day laborers, and outnumbered the anti-immigrant activists, who were joined by local neo-Nazis with swastika flags.

We forced them to station across the street instead, though they continued to hurl physical threats at us. We decided to march on them — and they fled and ran away. Around this time, I joined ISO and continued to help with these militant anti-fascist mobilizations to counter the Minutemen and SOS around LA for a while. They targeted other day laborers’ centers from Baldwin Park to Glendale.

I understood that this anti-fascist work is important especially as a Trotskyist. In Socialist Union, we read Trotsky’s writings on fascism, which taught us how great a threat it was to the working class and revolutionaries. And I knew already since the Prop 187 protests that when fascism comes to the United States it will take the form of anti-immigrant hysteria against Latino immigrants and also racism against Black communities.

Many of them are concentrated here in LA, which has the most proletarian of communities among Mexican, Salvadorean, Guatemalan and other groups. I also remembered reading about how neo-Nazis in Germany firebombed a house that killed Turkish and Kurdish immigrants, and I had a gut feeling that this kind of thing might soon spread here. I knew we must keep building and mobilizing mass coalitions to combat it.

We didn’t have to start from scratch. We had an important precedent: the successful mass movement against Prop 187. The direct action against the Minutemen and SOS was also developing a new core of LA militants focused on immigrant justice. Around the same time, other emergent leaders in other immigrant justice campaigns, like the La Economico Paro coalition, advocated for licenses for undocumented immigrants in the Inland Empire.

I was not a part of those efforts, but activists like Jesse Diaz were, and we all began joining forces for the mobilization against armed Minutemen mobilization at Campo, near San Diego, through a new coalition called La Tierra es de Todos. The coalition gathered radical immigrant justice activists, including more militant elements of larger immigrant groups like Gloria Saucedo from La Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, who took a firm approach against the moderates in the movement, represented by the “Somos America” coalition (which worked closely with the Democratic Party and was open to compromises like agreeing to guestworker programs).

La Tierra es de Todos members set up a camp half a mile away from the Minutemen, who would drive tri-wheelers around our camp and intimidate us with guns. Despite that, we marched into their camp to show that we were not afraid at one point. Police and media were surrounding us, so they didn’t shoot us. These consistent mobilizations against the fascists helped contain the anti-immigrant movement in California, contributing to those groups’ eventual demobilization and collapse.

Killing the Sensenbrenner Bill

PL: How did these different immigrant justice efforts merge into the 2006 protests against HR4437?

AM: The Sensenbrenner Bill drew national attention, and others in La Tierra es de Todos and I began discussing the need to build a larger coalition to combat it. We invited unions and other immigrant organizations like CARECEN to join us, and formed the “La Placita Olvera Pro-immigrant Working Group” (later “Coalition against the Sensenbrenner King Bill HR4437” and “March 25 Coalition”). The coalition organized a series of protests and demonstrations, from local vigils to pushing local city councils to pass resolutions opposing the bill, starting from December of 2005.

A few of us had been talking about the idea of a mass rally since the December meetings already, and later pushed for doing it on March 25. But, we were met with opposition from more conservative groups that later joined coalition meetings.

I remember the Catholic Church, United Farm Workers, Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA), SEIU and CSO sent representatives to the coalition meeting to try to cancel the March 25 demo, instead calling for us to join a more moderate procession at the downtown cathedral commemorating Cesar Chavez.

I saw this as an attempt to shut down the militancy of our mobilization, and supported other members arguing against it. Ultimately, after much debate, the vote to keep the March 25 mobilization won by one vote (thanks to the vote of an immigrant high schooler whose participation the church and those groups tried to unsuccessfully delegitimize). Most of those groups dropped out of the coalition after they failed to change the rally.

About a week later, almost half a million people marched against the bill in Chicago on March 10. We were all flabbergasted. I thought we could even double that number if Chicago could turn out that many people. After the Chicago march, all the moderate groups that had left returned to coalition meetings! They didn’t even bring up their previous disagreements — just came back with no shame. Everyone felt the momentum and knew our march would be huge.

We did a lot of turnout in the following weeks for March 25th. I was working as a gardener for businesses across the city at the time, so I could flyer and talk to people all over town about the rally as I worked. Our coalition members promoted it to their bases and went on talk shows, but what was most effective was gaining the support of DJs like Eddie “Piolin” Sotelo, whom many immigrant Latinos listened to.

Sotelo and other Spanish-speaking DJs were promoting the rally heavily, branding it as “historic” before it even happened. That was how La Gran Marcha became the largest single protest in LA history, drawing over a million protestors.

PL: And that was not the end of the movement yet. What led to the mass strike on Mayday a few weeks later?

AM: March 25 surpassed our expectations, and we knew we needed to keep escalating. I advocated for a general strike of immigrants on Mayday, which was supported by other militant coalition members. We must build on the momentum, and use this opportunity to bring Mayday back into the national consciousness.

Of course the unions, many nonprofits and the Church, opposed the strike, but we won that vote. We were so happy and beside ourselves: we were going to bring back Mayday! The moderate groups that opposed the general immigrants’ strike left the coalition for a second time and organized their own coalition and rally for Mayday. The Democrats didn’t want us to lead this militant fight.

Some of those who had supported the protests against Prop 187 were now leaders in the more moderate camp and left with them. We had representatives who tried to join their meetings to work together, but were told they weren’t allowed to come. What’s worse is that throughout April, the moderate groups held multiple press conferences actively telling immigrant workers not to strike, and students not to walk out of schools on Mayday.

Even Dolores Huerta was part of these press conferences, telling people not to risk their jobs, to keep earning money, and to take care of their families — all kinds of rhetoric and tactics to dissuade immigrants from mobilizing.

The strike still went forward, and there ended up being two marches on Mayday: ours in the morning and theirs later in the afternoon. Ours exceeded their size, and over half a million people showed up. The rallies were so large we could barely move in the streets. At our rally we encouraged the workers to keep fighting so that students could continue their walkouts, and said that we needed to build economic power to challenge the ruling class. Many people, including myself, supported the later action as well, which had no talk of striking and instructed people to vote.

We won a week or so later, and the Sensenbrenner bill was dropped. If you ask anyone in the immigrant community, they would say that we defeated the bill, not any politicians. The organized power of immigrant workers defeated that, and the workers knew.

It was like what Marx said about the self-emancipation of the working class in action. The people in Washington knew that immigrant workers were being radicalized, and they had to drop the bill to contain that upsurge.

Notes

- For more on Gabrielsky, see the interviewer’s obiturary of him published in ATC No. 211 (March/April 2021), https://againstthecurrent.org/atc211/gabe-gabrielsky-a-radical-affirmation/.

back to text - See Against The Current’s coverage of the Prop 187 protests in 1994 in No. 52, September/October 1994; 54, January/February 1995; and 55, March/April 1995, with articles by Angel Cervantes, Jim Lauderdale, Tim Marshall, Rachel Quinn and Gil Cedillo among others.

back to text - Socialist Union here refers to the grouping that existed in the 1970s, associated with Milt Zaslow, Gene Warren, etc., not the American Socialist Union led by Bert Cochran between 1953 and 1959 (although Zaslow was also part of this earlier formation).

back to text - Gene Warren later also became a member of Solidarity until his death. His late brother Ron Warren’s (also part of Socialist Union and Solidarity) obiturary of Gene was published in ATC No. 206, May/June 2020. The late Mike Davis wrote tributes to both Zaslow and Warren in ATC No. 71, November/December 1997 (see also Karin Baker and Patrick Quinn’s tribute to Milt and Edith Zaslow in the same issue) and No. 206, May/June 2020 respectively. Zaslow was a key mentor to the Warrens, just as the Warrens played a similar role for the interviewer.

back to text - Don White was a key leader of CISPES and a convenor of the LA Peace Center, a meeting location for the LA left in the 2000s. White passed away in 2008.

back to text

November-December 2024, ATC 233