Against the Current No. 226, September/October 2023

-

Palestine and Empire

— The Editors -

Supreme Court Outlaws Affirmative Action

— Malik Miah -

Supreme Court Denies Black Voting in Mississippi

— Malik Miah -

Chile 1973 -- The Original 9/11

— Oscar Mendoza -

Oppenheimer: The Man, the Book, the Movie

— Cliff Conner -

"Imperial Decline" in the Ukraine War

— David Finkel -

Free Boris Kagarlitsky!

— Russian Socialist Movement -

Banking for the Billions

— Luke Pretz -

AMLO's Mexico: Fourth Transformation?

— Dan La Botz - A World on Fire

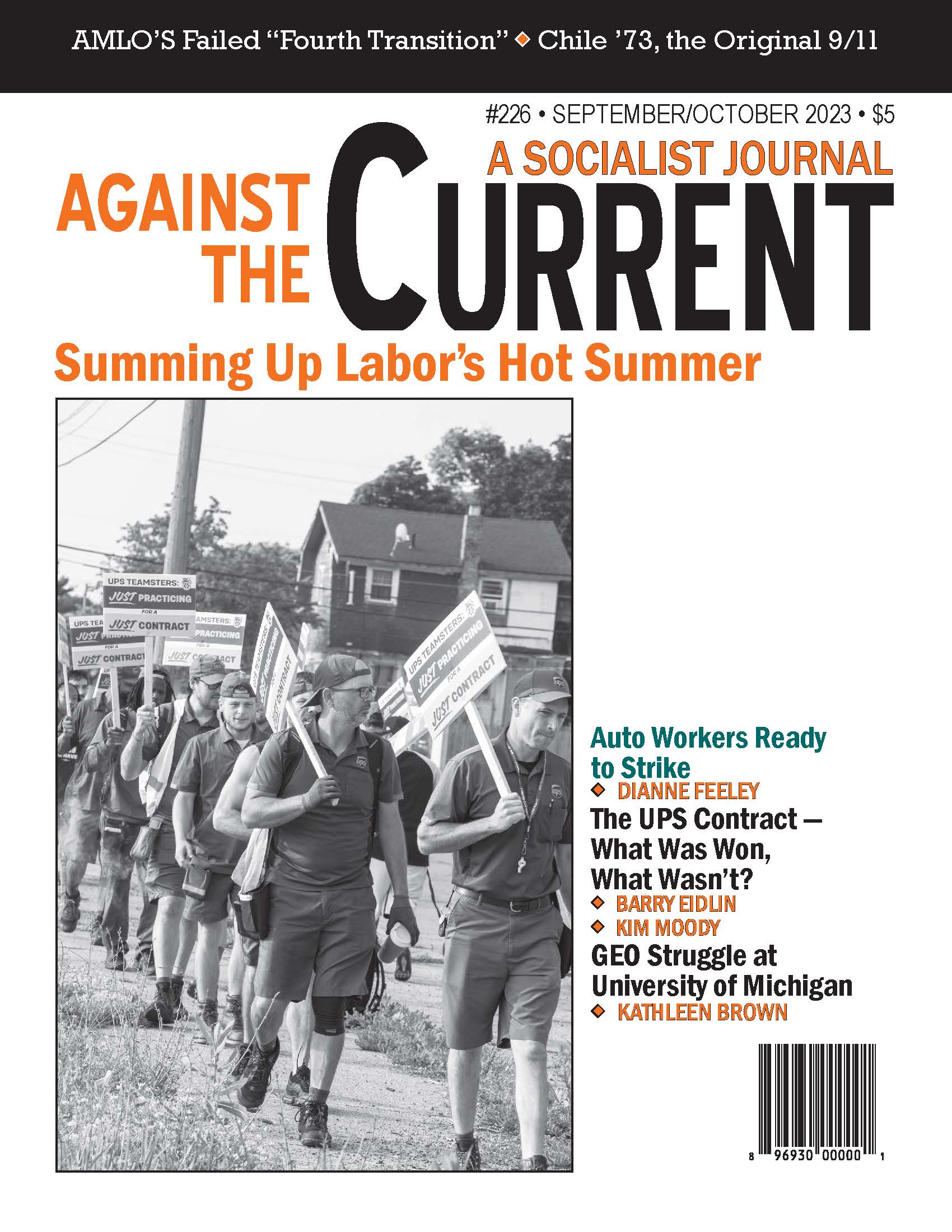

- Hot Labor Summer

- Introduction to Two Articles on Teamster-UPS Contract

-

The UPS Contract in Context

— Barry Eidlin -

Why the Rush to Settle?

— Kim Moody -

GEO vs. the University of Michigan

— Kathleen Brown -

UAW Strike Continues to Expand

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Revolution in Retrospect & Prospect

— Michael Principe -

The Red and the Queer

— Alan Wald -

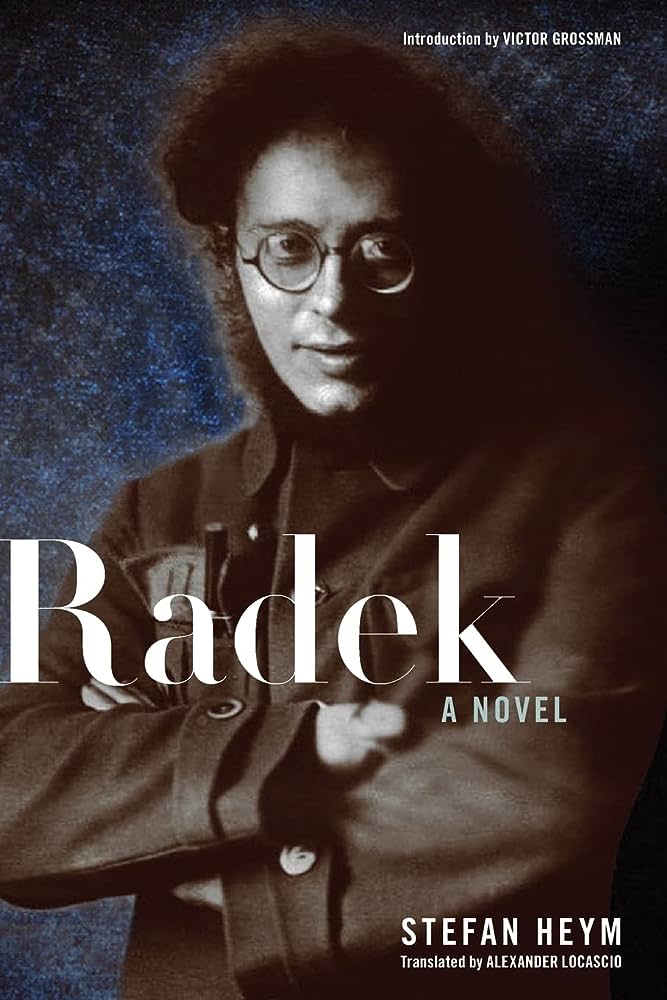

The Novel as Biography

— Ted McTaggart -

Anarcho-Marxism, Anyone?

— Paul Buhle -

The Myth of California Exposed

— Dianne Feeley

Ted McTaggart

Radek:

A Novel

By Stefan Heym

Monthly Review Press, 2022, 616 pages, $28 paper.

KARL RADEK IS best known to the world for his role in the Russian Revolution and the early years of the Soviet state and Communist International. A sometime ally of Leon Trotsky’s Bolshevik-Leninist Opposition, Radek capitulated to Stalin following a period of exile in Siberia in the late 1920s before eventually perishing in the Great Purges of the following decade.

Born Karl Bernhardovich Sobelsohn in 1885 to a Lithuanian-Jewish family in what is now Lviv, Ukraine (then known as Lemberg, part of the Austria-Hungarian empire) in Radek, like many of the leaders of the Russian Revolution, led a life that knew no national boundaries.

He joined the revolutionary social-democracy in Poland shortly before the 1905 revolution, where he played an active role in Warsaw as a member of Rosa Luxemburg’s Social-Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SKDPiL), and in a number of exile communities of revolutionary socialists throughout Europe between 1905 and 1917.

In his 1995 novel Radek, published in English translation for the first time last year by Monthly Review Press, Stefan Heym portrays Karl Radek as not only a man of the world but a perpetual outsider — a socially awkward contrarian with stereotypically Jewish features, thick glasses and a big mouth. In this, Heym likely saw in Karl Radek something of a kindred spirit.

Born Helmut Flieg to a Jewish family in Chemnitz, Germany in 1913, Heym was bullied as a child for being Jewish and was expelled from high school after publishing a poem critical of German militarism. After relocating to Berlin in the early 1930s, he fled to Prague in 1933, then to the United States after winning a scholarship to the University of Chicago in 1935.

After years working on German-language left-wing publications in the United States, in 1942 he published an English language novel, Hostages, which was made into a Hollywood feature the next year. By this time, Heym had enlisted in the U.S. military where he put his language skills to use as a propagandist. He continued in this role in the postwar years until his left-wing political views cost him his job.

Little, Brown published two more English language novels by Heym — The Crusaders in 1948 and The Eyes of Reason in 1951 — before the anti-Communist climate caused Heym to flee once more, now back to East Berlin.

Heym’s next English-language novel, Goldsborough, about striking miners in Pennsylvania, could not find a commercial publisher in the United States, though it was published in the original English in East Germany, and then in 1934 by Howard Fast’s Blue Heron Press.

German translations of this and prior English language novels established Heym as a celebrated novelist and journalist in East Germany. He straddled a fine line between critic and apologist for the East German regime that allowed him to be tolerated to a greater or lesser degree.

After the collapse of the German Democratic Republic, Heym was elected in 1994 to the Bundestag as a non-party candidate for the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) — a precursor by merger to Die Linke. He continued to publish novels until his sudden death in 2001.

The Novel as Biography

While works like Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton and Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis have intentionally blurred lines between historical record and fiction to good effect, Heym struggles to translate Radek’s life story into the narrative format of a novel. The reader is left to wonder whether Radek would not have been more successful as a traditional biography — a major advantage of which would be references.

The 600-plus page novel is separated into eight “books,” roughly corresponding to major episodes in Radek’s life and political activity. Childhood and adolescence are skipped over entirely, and his participation in the 1905 revolution is only fleetingly referenced.

The novel opens with Radek’s exclusion from the German Social-Democracy due to allegations from a fraternal organization, Luxemburg’s SDKPiL, regarding Radek’s moral character — failure to repay loans, stealing books from the party library, and befouling a comrade’s guest bedroom. The veracity of the allegations are never completely clarified, but the incident serves to introduce strained relationship between Radek and Luxemburg, as well as her partner and fellow SDKPiL leader Leo Jogiches, that resurfaces periodically throughout the novel.

From here, the novel plods along through the highlights of Radek’s years in exile through 1917. For hundreds of pages, we tread well-worn territory — the betrayal of the major parties of the Second International in August 1914, the Zimmerwald conference, the armored train through Germany on which Radek accompanied Lenin.

The writing is labored; as a premonition to the SPD’s betrayal in Germany, we are treated to pages of dialogue between Radek and Karl Liebknecht about how the German working class might respond when imperialist war inevitably breaks out; this and other similar exchanges throughout the book seem entirely unnecessary, as for example is the recounting of what happened at Zimmerwald.

Slightly more obscure is the story of Radek with Leon Trotsky at the negotiations for a separate peace with Germany in Brest after the Russian Revolution. Nevertheless, there is little to be found in this section that could not have been better portrayed in a proper biography or historical work.

Character development is a weak point throughout but particularly noticeable in Heym’s portrayals of women. Even those women who play key roles in revolutionary history and Radek’s own life are described first and foremost by their physical characteristics; both Radek and Heym seem unaware or unconcerned of the degree of sacrifice made by Radek’s wife Rosa, a physician, both in their years of exile and after the Russian Revolution.

As the primary breadwinner of the family, she appears to play a maternal figure both to their daughter and to Radek himself, who appears to lose all interest in Rosa soon after the birth of the child and only seems to regain any appreciation of her a few years later after the death of his new lover, the aristocrat turned journalist-revolutionary Larissa Reissner.

Adventure and Downfall

Radek takes on more of the characteristics of a novel during the Civil War years when Karl is forced to go incognito into Germany to provide assistance to the fledgling German Communist Party during the tumultuous weeks ending in Luxemburg and Liebknecht’s deaths. Radek’s challenges getting into and out of Germany, and surreal confinement in a palatial German prison where he learns he has been named the ambassador of Soviet Ukraine, are not without literary merit but not particularly compelling.

A subsequent mission into Germany around the time of the 1921 March action finds Radek and Reissner at a fancy hotel in disguise as tourists, evading the detection of German military officers also staying there. This episode has the feel of a James Bond adventure which, while exciting and fun, seems out of place within the broader novel.

In tone and substance, the novel is most successful in chronicling Radek’s political downfall following Stalin’s consolidation of power. As a member of the United Opposition together with Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev, Radek takes a leading role in an anti-Stalinist demonstration on the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. It would be the Opposition’s last gasp.

Radek subsequently faces exile to Siberia where, together with fellow exiles Preobrazhensky and Smilga, he continues to profess allegiance to the Opposition for a period of time before ultimately capitulating as a condition of return to Moscow. Despite his rehabilitation into the Stalinist machinery, Radek is downgraded from his quarters in the Kremlin to a squalid basement apartment and ekes out a meager existence as a journalist.

Radek’s life after his return to Moscow is permeated by an anxious, claustrophobic spirit. Tortured by the compromises he has had to make for his own survival, Radek tries to ease his conscience by writing ironic odes to Stalin that he imagines to be biting satire, but are taken by readers and censors alike at face value.

Heym knew all too well the fine line that must be walked by a critical-minded journalist in a Stalinist regime tolerant of criticism only within the strictest of parameters. It is likely for this reason that this part of the novel connects so effectively where earlier sections fall short.

After waiting for years for the other shoe to drop, Radek is finally accused of taking some part in the conspiracy to assassinate Kirov, a Stalinist leader in Leningrad killed in 1934. Zinoviev, Kamenev and many other Old Bolsheviks were also implicated in the regime’s frameup campaign (along with Trotsky, at the time in exile in France).

While spared summary execution in a farcical trial, he is sentenced to 10 years in prison. On Radek’s fate following sentencing, Heym offers no speculation, saying only that “No one knows who murdered him, and when, and in which camp, and on whose orders.” Heym and the reader alike can make an educated guess on whose orders the murder took place.

September-October 2023, ATC 226