Against the Current, No. 222, January/February 2023

-

The Smoke Thickens

— The Editors -

Inequality, Gender Apartheid & Revolt

— Suzi Weissman interviews Yassamine Mather -

Workers' Protests in Early December

— Yassamine Mather -

Student Strikes, Regime Cracks

— Yassamine Mather -

Repression Continues to Grow in Nicaragua

— William I. Robinson -

Queering "A League of Their Own"

— Catherine Z. Sameh -

A Radical's Industrial Experience

— David McCullough -

A New Day for UAW Members?

— Dianne Feeley - Ukraine's War of Survival

-

Future Struggles in Ukraine

— Sam Friedman -

Russia's Road Toward Fascism

— Zakhar Popovych - Race and Class

-

The Black Internationalism of William Gardner Smith

— Alan Wald -

Movement Challenges

— Owólabi Aboyade (William Copeland) -

George Floyd, A Life

— Malik Miah - Police Murder and State Coverup

- Reviews

-

Out of the Two-Party Trap

— Marsha Rummel -

Feminists Tell Their Own Stories

— Linda Loew -

Working-Class Fault Lines in China

— Listen Chen - In Memoriam

-

Mike Davis, 1946-2022

— Bryan D. Palmer

Bryan D. Palmer

“He was, as they say, an ‘incompressible algorithm,’ one of the most complex people that I’ve ever known. One of the kindest, one of the most tempestuous; one of the wryest, one of the most serious. So I loved him even if I didn’t fully know him. His death is simply a hole in the world.”(1)

TIME SPENT WITH with Mike Davis was always memorable. My first encounter with Mike was in 1981. He was working, and to all appearances squatting, at the London Meard Street offices of Verso/New Left Review. I dropped in unannounced, peddling a small book on E.P. Thompson that Toronto’s New Hogtown Press had just published. Mike was affability itself.

We went out to lunch “on the firm.” Pizza and beers turned into an afternoon of imbibing and telling tall tales. Mike’s were more elevated than mine. We ended up dropping in on Brigid Loughran, whom Mike met in Belfast in the late 1970s and married. The two were then separated, but on good terms.

With an impish look, Mike introduced me as the enfant terrible of Canadian labor history. (I have no idea how he came up with such an outrageous assessment!) There was much talk of “The Troubles,” and Brigid’s active role in the civil rights struggles that dominated politics in the Northern Ireland of the time. At some point Mike reached into a terrarium — the small London flat contained a number of them, which Brigid was temporarily looking after — and lifted a greenishly translucent serpent lovingly out of the container. I gaped in wonder as he began affectionately stroking the snake’s head, its tongue flickering in and out, seemingly in adoring appreciation. Welcome to Mike’s world.

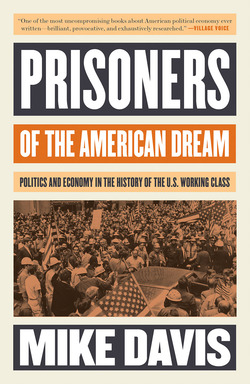

All of Mike Davis’ celebrated writing, justly-deserved fame, and ideologically-constructed notoriety lay ahead of him. I knew him only from his articles in Radical America and in Review, the journal of the State University of New York at Binghamton’s Braudel Center.(2) The latter essay, a 60+ page critical excursion through Michel Aglietta’s regulation school of capitalist crisis in the United States, caught the eye of Perry Anderson. Vouched for by comrades in the International Marxist Group with whom Mike was fraternizing in Belfast and Glasgow, Anderson offered Davis a $1000 advance for a yet-to-be-written book that would become Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class (1986). The sweetener was employment in the office of England’s premier New Left publisher.(3)

Early Life

Born in 1946, Mike was raised in the grit of working-class southern California. Fontana, birthplace of the Hell’s Angels, and El Cajon, adjacent to San Diego, were Mike’s home turf. His parents were an unlikely coming together of a unionized, Democratic Party voting, meat-cutting, father of Welsh heritage and a tougher-than-nails Irish Catholic mother who only had political eyes for Republican icon, Calvin Coolidge. “Unlike many of my contemporaries in the 1960s New Left, I never wore red diapers,” Mike noted with some pride.(4)

His mother and father, by all accounts, provided an immediate environment of nurturing love, but this was an isolated oasis hovering uncertainly above a backwater of bigotry. A racist frontier, composed equally of the culture of white cowboys, militarism, and socio-economic chanciness, the environs in which this Davis family domesticity was suspended exuded an evil yearning to erupt in violence that often punctured personal relations. “I actually believe that I have seen the devil or his moral equivalent in El Cajon,” Davis told an interviewer in 2008.(5)

What was a boy brought up in this milieu to do? Early drawn to a contradictory mix of interests that included natural science, the desert environment his father encouraged him to investigate, and the Devil Pups, a Marine Corps’ sponsored Youth Program for America, Davis soon outgrew conventional, if red-necked, wholesomeness. Devouring dragster pulp fiction — Henry Gregor Felson’s Street Rod (1953) being his antidote to the family reading material of choice, the Bible and Reader’s Digest collections in patented faux leather bindings — Mike flirted with the fast track of 1950s juvenile delinquency. Beer guzzling nights of joy riding culminated in a 1964 Valentine’s Day massacre in which the main victim was a powder-blue Chevy Davis ploughed into a wall, street racing with friends. His mother thought his night escapades best curbed by a stint in juvie, or perhaps even some hard time at San Quentin, but his dad brought him a copy of Ray Ginger’s biography of Eugene Debs as Mike recovered in hospital.

What really saved Davis from his nihilistic inclinations, however, was a Black activist in the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). A cousin’s husband, he introduced Mike to the civil rights movement at a 1962 protest targeting the lily-white Bank of America in downtown San Diego. This was the “burning bush” moment that brought Mike Davis into the fold of the revolutionary left.(6)

SDS Years

Two years later, after a disastrous few weeks enrolled at Reed College in Portland, Oregon — in which he was expelled for violating the school’s ban on men frequenting women’s dorms — Davis hopped a Greyhound bus to New York City, intent on working for the fledgling Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). He crossed paths in 1964-1965 with future luminaries of the New Left, Tom Hayden, Carl Oglesby, and Todd Gitlin, helping to organize a major protest at the Wall Street headquarters of Chase Manhattan Bank, then a material prop of the apartheid regime in South Africa.

By 1965, and the Watts Rebellion, Davis was back in California. He lived off the meagre avails of selling SDS pamphlets, journals, and newsletters, furnishing the movement’s Los Angeles office with typewriters and fixtures courtesy of some market-minded looters.

Davis made a pilgrimage to the house of Jackie Robinson’s mother, eager to help the Black community thwart the construction of a Pasadena freeway bisecting a historic African American district. The matriarch of the neighborhood patted Mike on the knee. “I think it would be better for you to go organize some white kids against racism,” she advised, adding, “This community can take care of itself.”(7)

Race ushered Mike into the eclectic radicalism of the 1960s. Class moved him into the struggles of the 1970s. The anti-war movement that, by 1968, placed SDS in the radicalizing limelight of the decade was the bridge traversing these two mobilizing initiatives.

Davis, like many 1960s radicals, was in motion towards Marxism. He may have been attracted to Maoism. Influenced by California’s Communist First Lady, Dorothy Healey, Mike joined the Party and worked for a time in its Progressive Bookstore. He befriended Angela Davis. But he was too much the dissident to last long in the CP.

Whether he was given the heave-ho as part of a pro-Chinese Cultural Revolution element, or because, along with an ex-Navy buddy, he physically tossed a Soviet attaché to the curb, is an open question. Mike preferred to present his departure from the Communist Party as a consequence of him man-handling the suspiciously well-dressed man who was lingering in discontent over bookshelves that Davis stacked with suspect subject matter, authored by Bukharin and Trotsky, Mao and Marcuse. Davis thought the Russian an FBI agent.

Davis’ 1960s came to an arresting end. He was taken into police custody, along with 286 others, in an SDS-sponsored protest at what is now known as California State University-Northridge. A peaceful November 1969 campus sit-in, where 3,000 students challenged the college administration’s banning of all demonstrations, rallies, and meetings, led to the largest mass arrest of the turbulent decade.(8)

LA Tour Guide

No longer an SDS organizer or employed by the Communist Party, Mike kicked around Los Angeles, living a marginal existence and trading stories with Black militants, down-and-outers, grifters, and small-time gamblers. An International Brotherhood of Teamsters program schooled him in the artistry of driving an 18-wheel tractor trailer. Securing and losing jobs, he eventually landed a gig as a tour bus guide.

Mike enlivened the standard patter on the fantasy sites of Disneyland and Hollywood by Night with an alternative rap on the underside of Los Angeles, rerouting tours so that he could talk about sites where white mobs massacred scores of Chinese in the 1870s or the McNamara brothers bombed the L.A. Times building in 1910. Reading the city’s history for the first time — drawing especially on Louis Adamic and Carey McWilliams — the seeds of Mike Davis’ Tartarean view of the City of Flowers and Sunshine lay in these years.(9)

His tour bus days came to a crashing halt with a 1973 strike. The coach drivers, whose crisply-pressed uniforms and conventional banter pandering to the mostly mainstream clientele Davis recoiled from, seemed to Mike a hopelessly conventional lot. Yet they managed to make the transition, not only to militancy, but to murderous conspiracy.

When an organized phalanx of strike breakers descended on the conflict, the mood of the drivers turned ugly. They convened a secret meeting of the brotherhood and voted to ante-up $400 each to hire two hit men to kill the leader of the scabs. Davis pleaded with his counterparts to build solidarity with other Los Angeles trade unionists, strengthen secondary picket lines, and shut the blacklegs and bosses down.

He was outvoted 39-1. “We’ve just got to kill the motherfucker,” his “namby-pamby” tour guide operators insisted. Only the incompetence of the hired killers, who were arrested for drunk driving before they could carry out their assignment, saved Davis and others from serious jail time.

Mike, arrested during the strike for ostensibly assaulting a scab with a picket sign, became part of the collateral damage of the eventual settlement: he was fired and court charges against him dropped. Or at least Mike claimed, his story-telling premised on the axiom that truth alone should never quite get in the way of a “fabulist” anecdote.(10)

The strike introduced Mike to some radical University of California-Los Angeles professors, among them Robert Brenner. Davis decided to join an exodus of former west coast SDSers into seminars discussing Marx’s Das Kapital and the transition from feudalism to capitalism. At 28, Mike began putting together his own eclectic agenda of intellectual interests. These included political economy, labor history, and urban ecology, the conceptual arsenal of his essays of the mid-to-late 1970s and a part of the foundation on which publications of the 1980s and 1990s would build.

Becoming A Writer

Sustained by a year-long scholarship from his father’s union, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America, Mike made his way to Scotland in 1978. He gravitated to Belfast, however, developing a deep fondness for the city, before finding himself, finally, in the 6 Meard Street digs of the New Left Review, an address not far removed from the alley-way-like thoroughfare’s bygone days of brothels and the traffic in transvestite sex.

How to characterize Mike’s oeuvre? Put simply, he was sui generis. His prodigious appetite for research, amazing capacity to recall everything that he read, extensive reach across centuries and continents, and a uniquely pugnacious style that combined metaphorical flourish, predictive intuitions, and relentless refusal to concede the least ground to capitalism’s destructive essence, resulted in a cavalcade of imaginative books that have no equal. In later writings, moreover, Davis encapsulated precisely the kind of synthetic sweep across the empirical and conceptual terrain of the natural, social, and human sciences demanded in an age of tragically synchronized climactic and capitalist crises.(11)

Prisoners of the American Dream, the first installment of this amazing output, was an unconventional study steeped in conventionality. It chronicled the political immolation of a working class captive of the ideology of democracy’s promise, whose most effective prison-house was the Democratic Party and its legion of ideologues.

Davis resituated the age-old questioning of American labor’s failure to develop socialist consciousness and establish a labor party. Writing against the background of Reaganism’s successful assault on trade unionism in the 1980s, Davis outlined how the U.S. working class had been structured into political cul-de-sacs.

The exhilarating wave of Debsian socialism that Davis insisted derived from an immigrant proletariat exploited economically and disenfranchised politically was absorbed in the Fordist “Americanization” of the 1940s and 1950s. It, in turn, destroyed the social and cultural basis of actually-existing forms of socialism and communism.

Only a new wave of radical protest could resuscitate a left-wing labor movement, bringing back to life the enervated trade unions. This would only happen if they took an internationalist and anti-racist turn, making common cause with liberation movements in the developing world and aligning unequivocally with the Black and Latino communities that were the newly-consolidating natural mass constituencies of the trade unions.(12)

Something of a cold shower thrown on the then-dominant social histories of United States workers written by labor historians such as Herbert G. Gutman and David Montgomery, Prisoners of the American Dream foreshadowed Davis’s future books. It refused to sugar-coat the bleak actualities of capitalism’s hegemony and contained invaluable intimations into what the future might hold and how it should unfold if socialism and human betterment were to advance.

Debunking LA Mythology

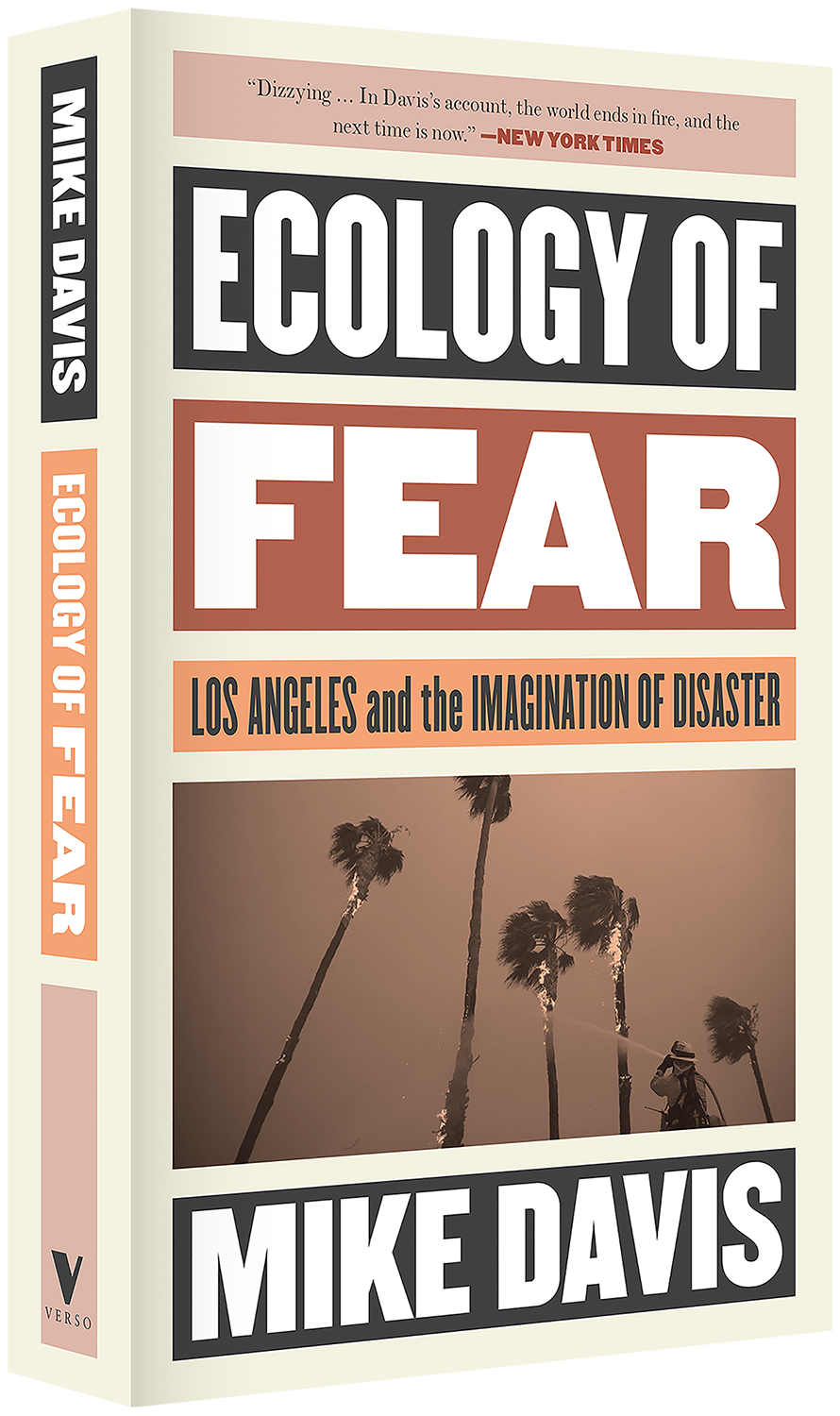

This rigorously anti-sentimental study was followed by two books that catapulted Davis into prominence within mainstream circles, where they became best sellers.

In debunking the mythology of Los Angeles as a coastal nirvana, presenting it instead as a metropolitan mirage resting hazily atop the scorched earth of capital, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future of Los Angeles (1990) and cology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (1998) elevated Mike Davis to “everyone’s favorite Rosetta Stone for translating the civic unrest.” Davis became canonized, however much he resisted the labeling, as a “prophet of doom.”

In outlining L.A.’s carceral, over-policed, fortress-like, racialized making and its rolling of the dice with respect to the potentially devastating consequences of environmental payback, Davis became associated with a particular catastrophic view of Los Angeles. But there was always much more to his commentary than this. City of Quartz managed to suggest, before they erupted, just why the Rodney King riots of 1992 were inevitable.

Ecology of Fear exposed an ecosystem of profit, with its blatant class inequalities and cavalier disregard of the price inevitably paid when nature and geology were overridden by acquisitive individualism and its penchant for accumulation. Now courted by commercial publishers and the recipient of prestigious awards and grants, Davis’s star was clearly on the rise.

The signature chapter in Ecology of Fear, “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” brilliantly outlined the class-differentiated political economy of fire in Los Angeles, juxtaposing two quite distinct districts. Posh mansions built in hills overlooking manicured beaches and impeccably-outfitted cappuccino bars were destined to burn, the high-rent district being situated within a natural wildfire ecology. Slumlord owned welfare lodgings and sweat shops in the dilapidated buildings of downtown L.A. were allowed to go up in flames, however, because it was profitable.

The tongue-in-cheek contention that Malibu should be allowed to burn, rather than being rebuilt again and again, was premised on an undeniable material logic: it made no sense to “develop” a place that nature periodically ravaged.

This environmentally responsible perspective rankled powerful interests, as did Davis’ accusation that inner city fire could be contained if only precautions were taken. This meant developing infrastructure rather than letting it lapse; enforcing regulations instead of ignoring them; enhancing welfare as opposed to chiseling away at it; and ending the practice of stacking immigrants atop one another in dilapidated and crowded hotels reconverted to housing, forcing recien illegados to work in dangerously abysmal fly-by-night “factories.” This cost money neither capital nor the state were willing to expend. Inner-city buildings burned because it paid the rich to allow them to do so, killing and displacing the poor in the process.

None of this went over well with those whose expense accounts, sales commissions, and extravagant living derived from the City of Angels’s sunny imaginary. They real estate magnates fought back. Davis found himself denounced as a fraud, his critically-acclaimed books reduced to nothing more than “fake, phoney, made-up, crackpot, bullshit.”

None of this helped Mike in the academic employment market which he did his best to snub his maverick nose at. For a time, he couldn’t buy a job in California, although his publication record was clearly extraordinary.(13)

“Political Ecology” Dramas

A flair for the dramatic statement became a signature feature of Mike’s enthralling narratives. Over the course of the 1980s Davis worked rigorously at the craft of writing, insisting that it was the most difficult thing he ever undertook.

Ecology of Fear’s unforgettable first line, for instance, takes the reader directly into the substance of the study: “Once or twice each decade, Hawaii sends Los Angeles a big wet kiss.” That this puckering up brought destruction in its wake did not have to be said.

Shoring up the panache of this prelude was Davis’ embrace of what he would subsequently, in Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World (2000), dub “political ecology,” an innovative and timely bringing together of environmental history and Marxist political economy. For Davis’ metaphor conveyed how irregular, but routine, storm systems swept warm, water-laden air from the Hawaiian archipelago south, hurling massive rainfalls, the equivalent of half of Los Angeles’ annual precipitation, on the Sunshine City. The ferocity of the consequent deluge set the stage for a depiction of L.A. as a city of potential calamity, an environment that inspired alarm.(14)

City of Quartz detailed capitalism’s making of the catastrophic and deformed social relations of everyday life, while Ecology of Fear chronicled just how the profit system rolled the dice, racking up big payouts as it gambled on environmental retribution not coming up snake eyes.

In Late Victorian Holocausts, Davis extended such insights globally, his text fusing the destructive agency of capital and its capacity to not only feed off ecological disaster but foment it. The book, which Perry Anderson regarded as “Mike’s masterpiece,” explored and exposed how imperialism, drought, and famine unfolded in India, northern China, and northeastern Brazil, filling the coffers of colonialism and decimating local populations.

Davis’ justifiably angry conclusion was that “imperial policies toward starving ‘subjects’ were often the exact moral equivalent of bombs dropped from 18,000 feet.” Capitalism had much to atone for.(15)

This deformed making of the third world was always pivotal in Mike’s understanding of the need for the revolutionary left to function in truly internationalist ways. Davis’s writing in the first decade of the 21st century pioneered transnational, global histories.

They offered wide-ranging commentaries on population movement from the impoverished global south to the job-rich American city, transforming, in the process, United States urban life; the immiseration of the slums of Africa, Asia, and Latin America that helped drive this process; and the desperate forms of refusal and resistance that evolved, pitting themselves against Western imperialism.

First and Third Worlds were indisputably linked in a cycle of imperial-induced violence. “Night after night,” concluded Davis with typical élan in Planet of Slums (2006), “hornetlike helicopter gunships stalk enigmatic enemies in the narrow streets of slum districts, pouring hellfire into shanties or fleeing cars. Every morning the slums reply with suicide bombers and eloquent explosions. If the empire can deploy Orwellian technologies of repression, its outcasts have the gods of chaos on their side.”

As more inhabitants of economies stunted by the world’s partition into spheres of influence ceded to a small number of capitalist states found themselves ground down, the dialectic of repression proved a two-way street. The car bomb raced fast and furious, chasing the fumes of forcible confinements and the bullets of brutish coercions, leaving no nation state immune from the fallout.

In Budda’s Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb (2007), Davis concluded: “[E]very laser- guided missile falling on an apartment house in southern Beirut or a mud-walled compound in Kandahar is a future suicide truck bomb headed for the center of Tel Aviv or perhaps downtown Los Angeles. Buda’s wagon truly has become the hot rod of the apocalypse.”(16)

Pandemic Prophecies

Three other books revived Davis’ stature as a seer, confirmed and deepened his place within the socialist tradition, and bid us farewell with a love letter to the romance of the 1960s, co-authored with his friend Jon Wiener.

The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu (2005) essentially predicted the Covid-19 pandemic. It shot a warning flare into the obviously compromised night vision of the World Health Organization.

Davis pointed an accusatory finger at the for-profit pharmaceutical industry. He exposed the roadblocks it was cavalierly placing on science’s ability to eradicate deadly pandemics, unleashed by the capitalist destruction of biodiversity. The resulting inter-species viral transmissions were now able to race at globalization’s enhanced, supply-chain, speed, leap-frogging from continent to continent in ways unfathomable during previous centuries.

In Old Gods, New Enigmas, Davis confirmed his commitments to old-time socialism’s values and material concerns, showing how they resonated with the accelerating doomsday warnings of threats to the Anthropocene. Like Trotsky, Davis was adamant that, “Those who cannot defend old positions will never conquer new ones.” He was convinced that Marxists must “ignite our imaginations by rediscovering those extraordinary discussions — and in some cases concrete experiments — in utopian urbanism that shaped socialist and anarchist thinking between the 1880s and 1930s. The alter mode that we believe is the only possible alternative to the new Dark Ages requires us to dream old dreams anew.”

In this spirit, Davis and Wiener took the title of their book on the radicalism of Los Angeles in this turbulent decade from the city’s quintessential rock band, The Doors, and their 1967 anthem to a moment of struggle and upheaval: “The time to hesitate is through/No time to wallow in the mire …/Try to set the night on fire.” For Mike, the 1960s contained tragedies aplenty, but also “social miracles and innumerable instances of unheralded courage and defiance.(17)

Defiance was Mike’s métier. As he told one journalist in the summer of 2022, his one regret was that he would not go out “in battle or at a barricade as I’ve always romantically imagined — you know, fighting.(18)

Final Struggle

Mike always fought best on the page, writing in ways meant to enlighten and enliven the revolutionary spirit. This demanded not only an indomitable will, but a physical robustness. But his strength to tell us his stories, historicize the future, and serve as our socialist seer — all accomplished through his prolific, prophetic, and powerful writing — was compromised in 2016.

Mike was diagnosed with a rare lymphoma, Waldenstrom’s macroglubulinema, and for the next six years he battled various cancers and lived with the debilitating side effects of interminable treatments. His wife of almost 25 years, Alessandra Moctezuma, a Latina artist, activist, and curator of considerable accomplishment, and his children — Róisín and Jack from previous marriages and the twins he co-parented with Alessandra, Cassandra and James Connolly — as well as countless friends, sustained him.

His resilience was extraordinary, his good humor admirable, his aspirations irrepressible. If he understood that he would never complete one of the studies he lovingly researched for decades, The “Heroes from Hell”: An Anthology of Revolutionary Outlaws and Anarchist Saints, Mike remained secretly at work on an ambitious project he insisted was “the perfect diversion from poor health”: Star Spangled Leviathan: An Economic History of American Nationalism. When the writing finally stopped definitively on 25 October 2002, the music Mike played for all of us died.(19)

It had been a long and exhilarating festival, a Woodstock for a post-1960s left that hung on Mike’s every note. Preoccupied in his last years with the dilemma of what was needed in the struggle against capitalism, Mike returned to the need for an “organization of organizers.”

As enthralled as he was with each fresh round of struggle, such as Occupy and the Arab Spring, he nonetheless always paused to ask, “what’s the next link in the chain (in Lenin’s sense) that needs to be grasped.” Only an organized movement could fulfill the promise of resistance, and in his last days Mike bemoaned its absence. “The biggest political problem in the United States right now,” he concluded, “has been the demoralization of tens of thousands, probably hundreds of thousands, of young activists.” They needed the discipline and direction of an organized socialist movement, not “solicitations from Democrats to support candidates.”

Mike’s last want was for “more noise in the street,” but for this bedlam to be buttressed by socialist mobilization sustained by the structure of an ongoing, evolving apparatus of revolutionaries.(20)

As we stare into the gaping hole that Mike Davis’s absence leaves, like a crater opening up before our long march along future anti-capitalist roads, we can pause to mourn, but need not be overtaken by despair. He left us as his legacy a library of thought, reflection and resolute dedication. Militants and mavericks, radicals, rebels, and revolutionaries, will be reading Mike Davis for decades to come. Honor him with acts of defiant dissent, determined demonstrations for social justice, resolute stands of class struggle and international solidarity, and by carrying high the standard of a fighting socialist movement.

Notes

1. Mike Davis, “Remembering a Friend,” Against the Current, 188 (May-June 2017). The words, written to memorialize Seymour Kramer, a founding member of Solidarity, long time San Francisco-Oakland area trade union activist, leader of a school bus driver’s union, and self-proclaimed “greatest white dancer,” with whom Mike Davis explored Trotskyist politics in the 1970s, are an apt epitaph for Mike himself.

2. Mike Davis, “The Stopwatch and the Wooden Shoe: Scientific Management and the Industrial Workers of the World,” Radical America, 9 (No. 1, 1975), 69-95; Davis, “‘Fordism’ in Crisis: A Review of Michel Aglietta’s Regulation et crises: L’experience des États-Unis,” Review, 2 (Fall 1978), 207-269.

3. Chris Bambery, “Mike Davis (1946-2022): A Class Fighter — Obituary,” Counterfire, 26 October 2022, https://counterfire.org/articles/opinion/23564-mike-dav-s-1946-2022-a-class-fighter-obituary; Suzi Weissman, “Mike Davis: A personal remembrance,” Solidarity, 27 October 2022, https://solidarity-us.org/mike-davis-a-personal-remembrance.

4. Mike Davis, “Let the ‘Red Special’ Shine its Light on Me,” introduction to Ray Ginger, The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2007), xi.

5. Lucy Raven, “Mike Davis: An Interview,” Bomb Magazine, 1 July 2008, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/mike-davis

6. Lewis MacAdams, “Jeremiah Among the Palms,” LA Weekly, 25 November 1998, https://laweekly.com/jeremiah-among-the-palms; Davis, “Let the ‘Red Special’ Shine its Light on Me,” in Ginger, The Bending Cross, xi-xvii; Mike Davis, “Crash Club: What happens when three sputtering economies collide,” in Davis, Be Realistic: Demand the Impossible (Chicago: Haymarket, 2012); Joann Wypijewski, “Mike, In Memory,” NLR Sidecar, 4 November 2022, https://newleftreview.org/sidecar; Bill Moyers, “Author Mike Davis: Interview,” 20 March 2009, https://billmoyers.com/api/ajax/?template=ajx=transcript&post+547

7. The above paragraphs draw on MacAdams, “Jeremiah Among the Palms.”

8. The above paragraphs draw on many sources, including conversations over the years with Mike Davis. See especially, MacAdams, “Jeremiah Among the Palms”; Gillian McCain and Ariella Thornhill, “Setting the Night on Fire: An Interview with Mike Davis,” Please Kill Me: This is What’s Cool, 2 November 2020, https://pleasekillme.com/mike-davis; Jon Wiener, “Mike Davis: 1946-2022 — A brilliant radical reporter with a novelist’s eye and an historian’s memory,” The Nation, 25 October 2022, https://thenation.com/article/culture/mike-davis-obituary; Jeff Weiss, “The LAnd Interview: Mike Davis,” https://thelandmag.com>the-land-inerview-mike-davis

9. MacAdams, “Jeremiah Among the Palms”; Sam Dean, “Mike Davis on Trucking,” Out-takes from an interview in the L.A. Times, 26 July 2022, https://samdean.com/?p+155.

10. Mike Davis, Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx’s Lost History (London and New York: Verso, 2018), xii; MacAdams, “Jeremiah Among the Palms”; Dean, “Mike Davis on Trucking”; Adam Shatz, “The American Earthquake: Mike Davis and the Politics of Disaster,” Linguafranca: The Review of American Life, 7 (September 1997); Sam Dean, “Mike Davis on an unfinished project and the American West,” Out-takes from an L.A. Times interview, 25 July 2022, https://samdean.com/?pageid=141

11. For a useful survey see Troy Vettese, “The Last Man to Know Everything: The Marxist-environmental historian Mike Davis has produced a rich corpus critical of capitalism,” Boston Review, 25 September 2018, https://bostonreview.net/articles/troy-vettese-great-synthesizer

12. Mike Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the American Working Class (New York and London: Verso, 1986).

13. The above paragraphs draw on Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (New York and London: Verso, 1990); Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (New York: Henry Holt, 1998); and Jeff Weiss, “The LAnd Interview.” For a thorough account of the attack on Davis, and a resolute defense of his writings see Jon Wiener, Historians in Trouble: Plagiarism, Fraud, and Politics in the Ivory Tower (New York and London: New Press, 2005), 106-116; and Alissa Walker, “Mike Davis was right,” Curbed, 26 October 2022, https://curbed.com/2022/10/mike-davis-obituary-los-angeles-urbanism.htlm/

14. Davis, Ecology of Fear, 5; Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World (New York and London: Verso, 2000), 15.

15. Alex Callinicos, “Mike Davis, 1946-2022 — we’ve lost a superb Marxist when we needed him most,” Socialist Worker, 27 October 2022, https://socialistworker.co.uk/obituaries/mike-davis-1946-2022-we’ve; Megan Day and Mike Davis, “Mike Davis on the Crimes of Capitalism and Socialism,” Jacobin, 23 October 2018, https://jacobin.com/2018/10/mike-davis-late-victorian-holocausts-famine-mao-stalin

16. Mike Davis, Magical Urbanism: Latinos Invent the US City (London and New York: Verso, 2000); Davis, Planet of Slums (New York and London: Verso, 2006), 206; Davis, Buda’s Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb (New York and London: Verso, 2007), 195.

17. Mike Davis, The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu (New York: New Press, 2005); and the updated The Monster Enters: Covid-19, Avian Flu, and the Plagues of Capitalism (London and New York: OR Books, 2020); Davis, Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx’s Lost History (New York and London: Verso, 2018), xxiii, 222; Leon Trotsky, In Defense of Marxism (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1973), 178; Mike Davis and Jon Wiener, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (New York and London: Verso, 2020), v, 642.

18. Sam Dean, “Mike Davis is still a damn good storyteller: Mike Davis on death, organizing, politics, climate change,” Los Angeles Times, 25 July 2022, https://www.latimes.com/lifestyle/image/story/2022-07-25/mike-davis-reflects-on-life-activism-climate-change-bernie-sanders-aoc-los-angeles-politics

19. For a discussion of one version of Heroes from Hell (I am in possession of a longer, more wide-reaching prospectus for a different edition) see “Artisans of Terror: Mike Davis Interviewed by Jon Wiener,” in Davis, In Praise of Barbarians: Essays Against Empire (Chicago: Haymarket, 2007), 263-277. See also Davis to Palmer, Email communications, 22 January 2017; 5 July 2021.

20. Mike Davis, “No More Bubblegum,” in Davis, Be Realistic: Demand the Impossible (Chicago: Haymarket, 2012); Davis, “Spring Confronts Winter,” New Left Review, 72 (November-December 2011); “Algérie Résistance; le blog de Mohsen Abdelmooumen,” 13 avril 2018, https://mohsenabdelmoumen.wordpress.com/2018/04/12/mike-davis-there-once-was-a-generation-of-lions; “Socialists are urgently looking for the future: American Marxist Mike Davis talks to Algerian journalist Mohsen Abdelmoumen,” MRonline, 25 April 2018, https://www.mronline.org; Dean, “Mike Davis is still a damn good storyteller.”

January-February 2023, ATC 222