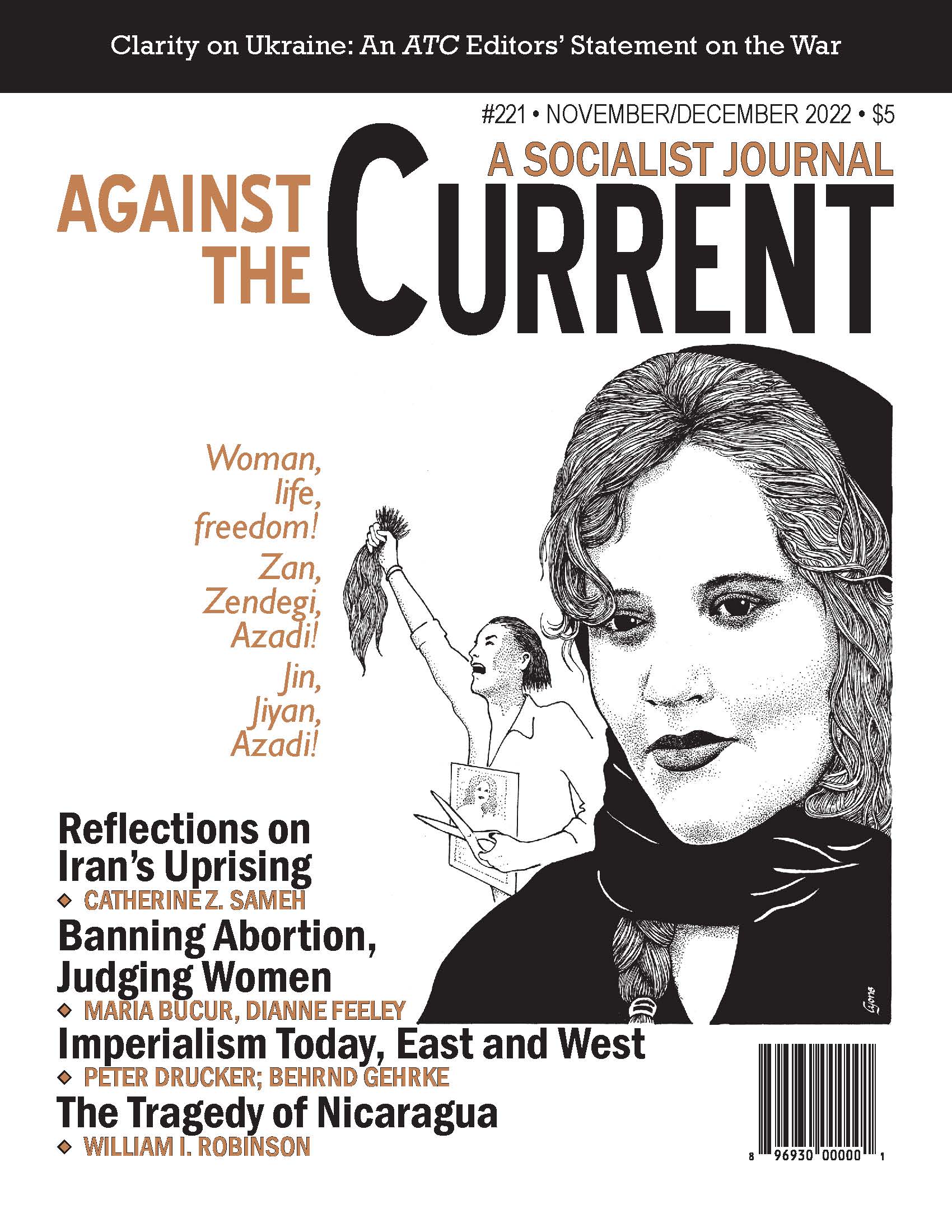

Against the Current, No. 221, November/December 2022

-

Clarity on Ukraine

— The Editors -

Reflections on “In Her Name”: The Meaning of Iran’s Uprising

— Catherine Z. Sameh -

Solidarity with the Protest Movement in Iran!

— Fourth International -

Surveilling and Judging Women

— Dianne Feeley -

Indiana's Abortion Ban: Lessons from Dystopia

— Maria Bucur -

Update on Indiana Ban

— Maria Bucur -

Safe Reproductive Health Services in Indiana

— Maria Bucur -

UAW Members Vote at Last

— Dianne Feeley -

Are Railroad Workers at an Impasse?

— Guy Miller -

Detroit Police Kill -- Again

— Malik Miah - Climate Change Makes You Sick

- Global Crisis

-

China: The Henan Rural Banks' Scandal

— Au Loong-yu -

Chile: Analysis of a Defeat

— Oscar Mendoza -

Support Ukrainian Resistance

— European Leftists -

Puerto Rico: Hurricanes & Neoliberal Ravages

— César J. Ayala -

Nicaragua: Daniel Ortega & the Ghost of Louis Bonaparte

— William I. Robinson - Imperialism Today

-

Imperialism Transformed

— Peter Drucker -

About Russian Neo-Imperialism

— Bernd Gehrke - Reviews

-

Veterans in Politics and Labor

— Steve Early & Suzanne Gordon -

Romance, Revolution and a World on Fire

— David McNally - In Memoriam

-

Milton Fisk, 1932-2022

— Patrick Brantlinger and several ATC editors -

Remembering Tim Schermerhorn

— Marsha Niemeijer -

For Rank and File Power

— Steve Downs

Guy Miller

“The carriers maintain that capital investment and risk are the reasons for their profits, not any contributions by labor.” —Management’s opening statement to the Presidential Emergency Board

AS THE CLOCK wound down to the September 16 impeding strike of 12 railroad unions(1) (representing 140,000 workers), Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh entered the final marathon bargaining session. With hours to spare, negotiators signed a tentative agreement. President Joe Biden called it “a big win for labor.”

The fact that the U.S. union bureaucracy often functions as a wholly owned subsidiary of the Democratic Party, and given that this is an election year with the two parties of the bosses running neck and neck, the pressure was on to accept an inferior contract. After all, we can’t afford to embarrass Joe Biden in the November elections. But that was then, now it seems it is possible that railroad workers will turn the contract down. Their red-hot anger over having to be on call 24/7 continues to burn.

The tentative agreement allows for one paid sick day per year and permits workers to take unpaid days without being penalized by strict attendance policies. Although the companies saw these changes as concessions, workers across the 12 unions may feel this is a drop in the bucket compared to what they need and deserve.

At the beginning of the negotiations, the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees (BMWE) had pushed for 13 sick days. Getting one day may have seemed like a sick joke. On October 10 members turned the tentative agreement down by 56%.

Four unions have ratified the agreement while three others have also voted it down. Next up are the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLET) for engineers and Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation (SMART) for conductors and trainmen.

These unions represent the operating crafts, similar to BMWE workers. All have stressed, repeatedly, that the major issue for them is not wages — although there have been no wage increases since 2019 — but quality of life issues.

If the tentative agreement is voted down, a strike could shut down the national rail system somewhere between November 19 and December 7 (safely after the elections). A strike before the elections is exactly what Marty Walsh feared, and worked to prevent.

Recent History

In 2021, the seven class-one railroads(2) in the U.S. and Canada reported a combined income of $27 billion, up from $14 billion just 10 years earlier. Better than that, the gravy train runs on an express track down the middle of Wall Street.

Excluding the privately owned Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad (BNSF), the six publicly traded class carriers paid out $186 billion in stock buy-backs and dividends to their shareholders over the last decade.

Those stunning figures have come at a high cost. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that in two short years, November 2018 to December 2020 (notice the timing, just before the pandemic) the railroad industry lost 40,000 jobs. But the amount of freight traffic only grew during those years.

Ross Grooter, an engineer on the Union Pacific, and co-chair of Railroad Workers United, summed up the situation succinctly: “The job has just become fewer people, doing more work faster.”

In 2022, as the strike deadline drew closer, media war drums began beating to the tune of “supply chain crisis” and the inevitable “national emergency.” Hardly a newspaper article or a television report failed to mention the impending doom that a national railroad strike would cause to the economy.

The irony of the supply-chain-crisis narrative is that the railroads and trucking industry have made it a reality. Decades of lean production have driven tens of thousands of experienced employees out of the transportation industry. The mania for “just in time” production means there is no margin for error when the inevitable rainy day finally arrives. Baby formula runs out in hours, paper towels disappear off the shelves in days, and auto plants are forced to shut down when needed parts are stuck in ships off the coast of Long Beach, California.

Now, in a textbook example of chutzpah, the carriers cry: supply chain crisis.

How Railroads Modernized

Beginning around 1950 and extending into the middle 1970s, U.S. industries began shoring up their profitability through various mechanisms such as privatization, deregulation and globalization. This era of neoliberalism gave rise to lean production and “just in time” supply chains.

But central to neoliberalism was beating back the defiant working class of the post-Vietnam War years. One third of workers were union members, strikes were more common and wage increases were the rule of the day. It would take ten years to turn the militant generation of Lordstown into the generation of the crushed PATCO air controllers strike.

Different industries presented different challenges to the downsizers. Some unions could be brought to heel suddenly, but in other industries it happened gradually. Railroads, partly because of their spread-out and relatively diffuse nature, would take a little longer.

By the early 1970s, I noticed firemen (essentially assistant engineers) disappearing from commuter trains. It wasn’t much longer until cabooses on road trains went the way of milk in bottles. Switching crews went from four to three, and finally, to two. Once ubiquitous yard clerks were replaced by cameras, GPS began to track the cabs that shuttled crews between yards.

Even Warren Buffett, the seventh richest man on the planet, got in on the act through his Berkshire Hathaway company. The company plunked down a cool $44 billion to buy the BNSF, the second largest railroad in the United States in 2009. By the time I retired later that year, the carriers were set to play hardball in earnest. The last, and perhaps most upsetting, was the arrival of remote-controlled switch engines in the yards. With remotes, instead of a hogger behind the throttle, there was a black control box hanging around your neck.

In the 13 years since I last “turned a wheel,” the seven class-one carriers have gone from dreaming of a “lean work force” to demanding an emaciated one.

Quality of Life

The primary quality of life issue is the brutal nature of being on call 24/7. Unless you’ve experienced a work life tethered to the next telephone call, it may be difficult to grasp how torturous the situation can be.

In the past, operating crews would go from point A to point B and then back to A. Today it can be from A to B to C before going back to A, leading to even more time away from home.

I was lucky. In my railroad career I only spent two years on the less onerous yard extra board. Still, until this day, I feel a jolt of anxiety whenever I hear a telephone ring.

Here’s how a typical scenario of being on call might work: After two or more days away from home, you tie up (finish your assignment), which puts you on the bottom of the to-be-called list, and the vigil of waiting for your next call begins. Because of cutbacks and people leaving the industry due to exhaustion, the list is about one-third shorter than it used to be, which makes your vigil one-third shorter.

Added into the new reality is the wildly unpredictable Precision Scheduling Railroading (PSR). (I will discuss PSR later, but for now, just know there is nothing “precise” about its effect on your schedule.)

The traditional American fulltime job is based on the five-day work week, usually with Saturdays and Sundays off. This provides, at least, 104 days off built into the system. Either paid or unpaid, eight holidays can often be counted on. Many jobs provide vacations; with 15 years seniority three weeks is the norm.

Five sick days are not uncommon, especially in a unionized workplace. That comes to 138 free days, not extraordinary. It’s fewer days off than a medieval peasant had, but it does provide a chance to structure a balanced life. A comparable freight engineer or conductor may have the three weeks’ vacation — 21 days, full stop.

It gets worse. This past February, the BNSF instituted a new attendance policy called “Hi-Viz” (for high visibility). The patronizing name is only the beginning of its faults. The system “awards” each employee 30 attendance points, more or less for life.

Any absence, for any reason, results in losing points. An out-of-town wedding for two days might cost you 10 points, a last-minute flooded basement is perhaps good for six more, mark off with a head cold or a child’s birthday and within six months you’re in dangerous territory.

When the 30 points are exhausted, you are subject to your first round of discipline: 10 days off without pay. After that, the clock starts again, this time with only 15 points. Use those up and you’re knocking at the door of dismissal. At some point, it becomes easier to skip a funeral here, or go to work sick there.

One engineer puts it this way in the online magazine Motherboard: “Hi Viz turns your life into a scoreboard. And you have no way, whatsoever, of knowing what that scoreboard is going to say.”

BNSF knew the anger their drastic new system would generate, and filed a preemptive suit in a Texas district federal court. The suit sought to block unions from taking any action, including picketing, work stoppages, and slowdowns.

The judge took the side of the company, ruling that the Hi Viz dispute fell under the category of “minor” under the provisions of the Railway Labor Act. Therefore unions had no recourse to action when it came to the BNSF’s new attendance policy.

Although mostly behind the scenes, the non-operating crafts have also taken a beating during the last several decades. For example, Maintenance of Way (aka track workers, organized in the BMWE) have had their work territory expanded to the point where they are expected to “commute” as far as a thousand miles from home.

Travel allowances and meal stipends are based on a 1990 agreement which forced BMWE members to sleep in their cars after their work period ends. Their condition was so egregious that even the Presidential Emergency Board was forced to make an exception and rule on this Quality of Life issue.

Precision Scheduling Railroading

Added to the barbaric attendance policy, another cause of the white-hot anger among railroaders is the train makeup system, dubbed “Precision Scheduling Railroading” (PSR). Together with draconian work schedules, this past July, these two factors resulted in an astonishing 99.5% strike authorization vote by 24,000 BLET engineers. The stage was set for a September showdown.

Precision Scheduling Railroading, a misnomer of Orwellian proportions, is not some master plan that would move freight more efficiently, but rather is in essence a sleazy business strategy. It is one of those rare ideas that manage to piss off both employees and customers.

At one time, the railroads placed a high priority of blocking cars in their over-the-road trains. Through the use of classification, or hump yards, trains were built up carefully to deliver specific freight to specific destinations. Train makeup emphasized the quality of a train’s manifest: auto racks lined up for a GM plant, double stacks for intermodal facilities, grain cars for agricultural centers.

With the advent of PSR, it’s now all about assembling the biggest trains in the shortest amount of time. PSR has resulted in shuttering hump yards, mothballing engines, downgrading intermodal yards and chronic understaffing.

The magazine Freight Ways points to a 25% increase in average train length. By most accounts, this is an understatement. It’s not unusual for carriers to glom two standard trains together, creating monsters of two-and-a-half to three miles long.

There’s no time for blocking, no time for proper inspection. The only concern is how fast these behemoths can, as the railroad saying goes, “get out of Dodge.”

The pressure PSR creates extends beyond the operating department. One example is the important job of signal maintainer, the men and women who keep the essential signals along the right of way working properly. Due to cutbacks, maintainers are forced to cover a bigger area. Before they can begin work they must get permission from a dispatcher.

The dispatchers, also under pressure, are reluctant to take a stretch of track out of service for the time needed to properly work on signals. As a result, it becomes tempting for the maintainers to do a less-than-thorough inspection.

Before a train leaves a terminal, car inspectors need to look over every car in the outbound trains. They are checking for broken brake pipes, open plugged doors, malfunctioning coupling devices, ladders, crosswalks, air hoses and anything else that could cause a calamity at 50 miles an hour. Inspectors used to take three minutes to check both sides of a car, now they are told to take one minute.

Profits Are the Bottom Line

In an October 2021 statement, the Transportation Trades Department of the AFL-CIO wrote about Precision Scheduling Railroading:

“PSR works for the few wealthy investors, who have little concern for anything other than their bottom lines.

“These investors are fickle, and when they have extracted every last cent out of the railroad industry, they will move to the next sector. Meanwhile we will be left with a hollowed out system that does not serve the customer, has abandoned safety, and has pushed out thousands of skilled workers, who will never return.”

The railroad bosses have two lists stuffed in the vest pockets of their suits. One is a wish list, and the other is a hit list. At the top of both lists is reducing all crews to one employee on freight trains. Think about it: one person, three miles of train, with dozens of cars of hazardous material, rumbling past your house at two AM.

The one-person crew didn’t work out so well for the people of Lac Megantic, Quebec on July 6, 2013. An overworked engineer, forced to do conductor’s work, allegedly failed to tie “sufficient” hand brakes on a train he had just brought over the road, with 72 tank cars carrying high-volatility crude oil. The result was 47 deaths when the brakes failed and the train rolled down a hill, derailed at high speed and exploded, incinerating the town center.

Ron Kaminkow, General Secretary, Railroad Workers United,(3) poses a series of questions:

“What if the engineer has a heart attack? How will the train make a backup move? What happens when the train hits a vehicle or pedestrian? How will a single train crew member deal with ‘bad order’ equipment in his or her train? Or set out or pick up cars en route? What about calling signals? What about copying mandatory directives and reminders of slow orders?”

I would add: What about if an overworked engineer falls asleep? It’s been known to happen. Who will cut road crossings if the train is stalled and emergency vehicles need to cross through?

Time magazine reports a growing schism between some highly placed members of railroad management, including a few CEOs, and Wall Street investors.

Some in management, with at least a modicum of on-the-ground savvy, realize that an investment in infrastructure (tracks, engines etc.), will pay off in long-term market share. Meanwhile, the Wall Street boys are obsessed with short-term profits, their strategy is “take the money and run.”

Pete Swan, a professor of logistics and operation management at Penn State, told CNN: “Railroad Management has been focused on maximizing payouts to the shareholders and their return on assets, not the quality of service.”

No matter the long-range thinking, Wall Street and management are united on one thing: it’s all about the profits.

Long Path to a Contract

More than two years of negotiations, the railroad workers in all 12 unions felt they were out of options and voted to strike. At this point the Railway Labor Act (RLA) of 1926 was set into motion. The RLA includes a convoluted set of stages, including 60-day cooling-off periods, a Presidential Emergency Board,(4) arbitrary distinctions between major and minor grievances, and ultimately a determination to be made by Congress whether a work stoppage constitutes a “national emergency.” Spoiler alert: It almost always does.

For the first time in memory, all 12 unions attempted to bargain in a coalition as opposed to separately. In the past, carriers would work out a deal with a union and then use it to set a pattern for the other settlements. Then when the Presidential Emergency Board released its findings, the coalition essentially fractured and unions started making tentative agreements based on the PEB findings. Part of their agreements had “me too” clauses in case some other unions got a better deal. Pretty despicable!

During the last national strike in 1991, Congress voted 400 to 5 to send us back to work after 23 hours. Five — that was the number of friends we had in Congress. In 1950 Harry Truman, another of our “friends,” issued an executive order putting the country’s railroads under the control of the U.S. Army.

This convoluted process is the mechanism to cool down workers’ anger. Yet this time around, union members threaded their way through the labyrinth. They were within hours of a strike.

No matter how the current contract is finally resolved, the strike threat has put the companies on notice. The right to a schedule is not just an issue for the nation’s railroad workers but also for those working in Amazon warehouses and at the corner Starbucks. Working people have the right to a life and the responsibility to take the future into their own hands.

Notes

- The 12 unions on American railroads are organized on a craft basis. This arrangement is one of the legacies of the crushing of the historic Pullman Strike of 1894. Three of these are much larger than the others.

back to text - Class-One Railroads are determined by annual revenue. The seven that made the cut are: BLSF Railway Co., Canadian National Railway, Canadian Pacific, CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern Railway Co., Norfolk Southern, and the Union Pacific Railroad.

back to text - Railroad Workers United is a rank-and-file cross craft reform movement of railroad workers.

back to text - The Presidential Emergency Board (PEB) The Railway Labor Act allows the president to appoint an emergency board. The creation of the emergency board delays a strike, or lockout, for sixty days, and makes recommendations for the settlement of the dispute.

back to text

November-December 2022, ATC 221