Against the Current, No. 220, September/October 2022

-

It's All Out in the Open

— The Editors -

Fighting for Reproductive Justice

— Shui-yin Sharon Yam -

California's Reparations Task Force

— Malik Miah -

The "Bruce's Beach"

— Malik Miah -

2022 Labor Notes Conference

— Dianne Feeley -

Bill Gates and Techno-fix Delusions

— M.V. Ramana and Cassandra Jeffery -

The Fight Over Inflation

— Suzi Weissman interviews Robert Brenner -

UAW Convention: Change in the Wind

— Dianne Feeley -

International Tribunal Verdict: "Guilty of Genocide"

— Steve Bloom -

Philippines: Continuity of Violence

— Alex de Jong -

"Can I at Least Have My Scarf?"

— Anan Ameri -

Echoes of Money in Times Past

— Daniel Johnson - Reviews

-

The War Upon Us

— Jerry Harris -

Texas: Darkness Before Dawn

— Joshua DeVries -

New Veterans, New and Old Problem

— Ronald Citkowski -

Anan Ameri, Life and Community

— Dalia Gomaa -

Joe Burns' Class Struggle Unionism

— Marian Swerdlow -

Radical Memories of Two Generations

— Paul Buhle - In Memoriam

-

Leo Frumkin, 1928-2022

— Sherry Frumkin -

Living with Political Clarity: A Tribute to Xiang Qing

— Au Loong-yu and translated by Promise Li -

Alain Krivine, 1941-2022

— John Barzman

Daniel Johnson

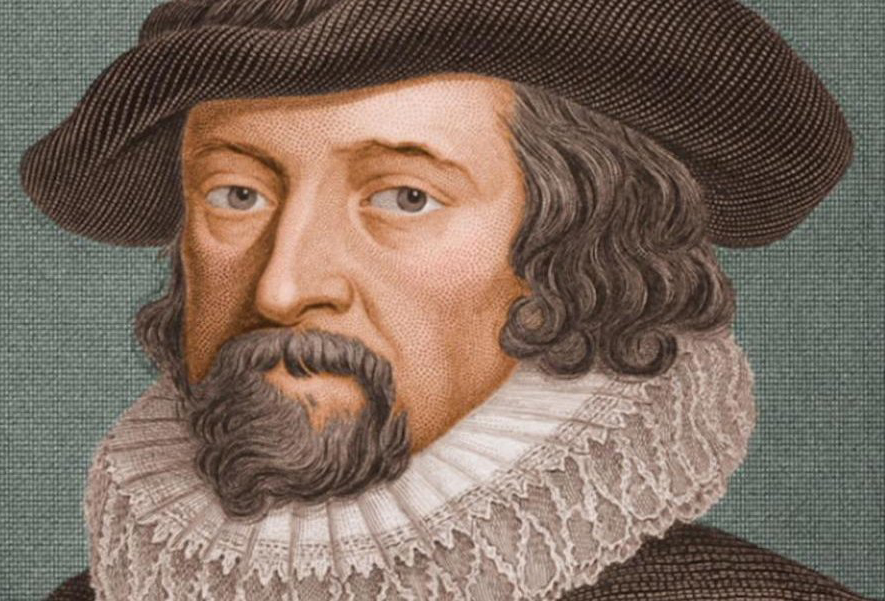

THE PHILOSOPHER FRANCIS Bacon once wrote that “money is like muck, not good except it be spread.” Known today primarily as Renaissance England’s foremost advocate of modern scientific methods, Bacon was also not averse to dispensing folksy medieval proverbs.

Indeed, for most people in the later Middle Ages and early modern Europe it was common knowledge that money, like shit, served little purpose (and stank) when hoarded. When spread widely, however, it acted as a fertilizer that promoted growth. Written in the wake of a popular rebellion in the English Midlands in 1607, Bacon’s “Of Seditions and Troubles” was a cautionary tale that warned rulers of the dangers of extreme inequality.(1)

Since the Great Recession of 2008, the fundamentally political nature of money has reentered public consciousness. Journalists and academics have noted that until the creation of central banking systems (the U.S. Federal Reserve was established in 1913) monetary policy was a frequent subject of popular political debate.(2)

Post-Great Recession policies of quantitative easing, the emergence of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) on the progressive left and cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin on the libertarian right, and fiscal measures to mitigate the economic fallout from COVID-19 have revealed money to be subject to social and political action.(3)

If analysts have rediscovered money’s political roots, few have noted that it was in Bacon’s time, roughly the era between the 16th and 18th centuries, that modern ideas about money were forged. The development of agrarian capitalism in England engendered social relations dependent on markets, cash, and new forms of credit. Financial innovations were central to economic development, and by the late 17th century England and its American colonies began novel experiments with paper monies.

While understanding modern developments like the gold standard and central banking is important, awareness of the historical relationship between money and capitalism — and opposition to it — also requires a longer view.(4)

Money is not what comes to mind when most people think of Francis Bacon. The same is true of later Enlightenment figures like John Locke, Isaac Newton, and Benjamin Franklin. Yet these men were all deeply engaged in the politics of currency during a formative period of monetary development.

Importantly, working people in the age of agrarian and merchant capitalism also felt entitled to engage in debates and direct actions over monetary policy and credit relations.

They knew that money was not simply a natural consequence of market exchange and the emergence of the modern state but was fundamentally about relations of power. And if it was about power, it was also political, and could therefore be put in the service of the common good.

England’s Culture of Money

In 1578, seven years after Parliament legalized an interest rate of 8%, the clergyman Philipp Caesar attacked England’s “damnable sect of usurers.” His blistering 75-page polemic cited authorities from Aristotle to Aquinas to argue that the “breeding of money” was unnatural, unlawful, and immoral.

Caesar also referenced unrepayable levels of debt when he noted that in ancient Rome debtors were often “compelled to give their bodies into slavery.” Debt bondage led to popular insurrections and the abolition of forced debt slavery — a popular victory in Rome that, Caesar implied, could be repeated should the English state not rethink its policy.(5)

The usury law and Caesar’s diatribe were symptoms of a society undergoing major change. The enclosure movement, which privatized common lands for commercial agricultural production, removed many people’s traditional sources of subsistence. The consolidation of farms and the transition from arable to less labor-intensive pasture lands for wool production threw multitudes off the land and out of work. Common people responded to enclosures by pulling down fences and destroying hedges.(6)

Intellectuals also took note of profound changes then underway. Thomas More attacked enclosures and the raising of sheep in Utopia, first published in 1516. Raphael Hythloday, More’s fictional world traveler who visited the South Pacific Commonwealth of Utopia, was scandalized by English society, noting that previously “sheep used to be so meek and eat so little.” Now, however, “they are becoming so greedy and wild that they devour human beings themselves.”

In communist Utopia, by contrast, not only was private property abolished, so too was money. For More (or rather Hythloday), contemporaries’ fascination with rare metals like silver and gold was an unfortunate product of human folly. Things of real value — air, water, soil — were freely given by Nature. Utopia’s value system represented a rejection of a growing obsession with monetary accumulation.(7)

More was executed in 1535 — not for being a communist (which he wasn’t), but for refusing to acknowledge the supremacy of King Henry VIII and his new Church of England. Henry’s break with the papacy and the creation of a national church was followed by the dissolution of the monasteries, institutions of social welfare whose lands were quickly purchased by the gentry.(8)

While his destruction of the monasteries is well-known, in 1544 Henry also initiated the debasement of English coin to pay for war with France and his lavish lifestyle. Though the disastrous inflationary policy was abandoned in 1551, in subsequent decades prices continued to rise while wages stagnated.

New forms of credit substituted for a lack of cash, transforming traditional social relationships and producing an explosion of lawsuits, defaults, and incarceration in debtor’s prison.(9) Critics lamented the profiteering and corruption of merchants and landlords, while popular hostility to debtors’ prison and exploitative jailers became a feature of English society that lasted well into the 19th century.

The growing importance of money, credit, and debt in Renaissance England’s “golden age” was evident in popular culture. Thomas Lupton’s All for Money, first performed in London in 1577, examined the threat to traditional morality posed by a profit-oriented society.

So, too, in different ways did the plays of Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare. If commerce corroded traditional bonds and unrepayable debt portended unfreedom, currency also offered pleasures of consumption unimaginable to previous generations.(10)

Money’s ability to reduce customary relations to a universal cash equivalent was satirized by John Taylor in A Shillling; Or, the Travailes of Twelve-Pence (1621). The poem’s narrator, a personified shilling, recounts its adventures from the mines of Potosi (site of fabulous silver wealth for the Spanish Empire in Bolivia) to contemporary England. Born from the labor of an enslaved Indigenous miner, the shilling voyages across the Atlantic and passes through the hands of hundreds of people from every imaginable walk of life. /p>

Taylor suggests the otherworldly power of money when noting that the life of the twelve-pence “is like a perpetual motion in continual travel, to whose journey there can be no end, until the world come to a final dissolution and period.”(11)

Money was also prominent in a burgeoning literature of crime. In an environment of monetary scarcity some localities resorted to the use of unofficial tokens for trade; according to historian Deborah Valenze there were more than 3,000 “tokeners” in mid-17th century London.(12)

Even more common was the distribution of counterfeit and “clipped” coin. Clipping involved shaving the edges off silver coins, with the shavings melted down into bullion and then sold abroad or used to manufacture more coin.

Importantly, most of the English population did not see coin clipping and counterfeiting as particularly nefarious acts. Though counterfeiting was made a capital offense under Queen Elizabeth I, many people saw money-makers as skilled craftsmen who made currency more plentiful when the state failed to provide an adequate medium of exchange. The representation of some of these figures in crime stories reinforced an image of the counterfeiting outlaw as a popular hero.(13)

From Common Good to Public Interest

Social critics in Tudor England used a language of the “commonweal” to attack the greed and antisocial hoarding of money and resources that characterized the new economic order. By the early 17th century, however, some theorists suggested that since the desire for private gain was part of human nature, perhaps this desire could be harnessed for the general betterment of the nation.

Economic writers increasingly promoted improved business practices, the rationalization of agriculture, and domestic industrial production to enhance national economic growth. Justifications of the pursuit of private interest substituted an individualized and abstract “public interest” for the collective commonweal.(14)

New concepts and forms of measurement lent scientific support to supporters of individual accumulation. William Petty, a founding theorist of political economy (or “political arithmetic”), pioneered the use of statistics to measure time, space, and population — the latter now monetized in terms of labor productivity. Classifying working people in relation to their economic value quantified the potential wealth of the nation; it also instrumentalized and objectified the laboring population.(15)

The most notorious proponent of the pursuit of private gain in the alleged public interest was Bernard Mandeville, a physician originally from Rotterdam in the Netherlands. In Fable of the Bees; or, Private Vices, Public Benefits, Mandeville turned conventional wisdom on its head by arguing that what made man sociable was not his desire for company, good nature, friendliness, or other virtues.

Rather, it was his “vilest and most hateful qualities” of self-love that were “the most necessary accomplishments to fit him for the largest and, according to the world, the happiest and most flourishing societies.”(16) Mandeville also supported an emerging “utility of poverty” social theory. According to this idea, keeping wages low and money scarce encouraged the poor to labor industriously while creating a favorable balance of trade by increasing exports.

Working people’s ignorance of the world beyond work was also essential to “public” happiness. For Mandeville the movement for free charity schools was a serious error, for the more workers knew of the world, the less willingly would they endure the “hardships and fatigues” of their labor.(17)

Mandeville’s belief in the public virtues of private vice was too extreme for mainstream English society. The thought of John Locke, the father of modern liberalism, was by contrast enormously influential.

In Locke’s view the historical introduction of money to exchange removed any natural limitations to appropriation, thereby invalidating the idea that everyone should have access to what is required for the satisfaction of needs. According to the political theorist C.B. Macpherson, Locke’s most important philosophical achievement was “to base the property right on natural right and natural law, and then to remove all the natural law limits from the property right.”(18) Locke’s famed views of property were unthinkable without the technology of money.

Locke was also a founding shareholder in the Bank of England, established in 1694 to fund war with France. The bank was the first to make loans to the government in paper notes rather than coins, while those who bought interest-bearing shares in the bank could sell them on a developing stock market. The bank’s union of private and public interests was a pivotal moment in the history of modern money; it was a political project that tied a nascent capitalist class to the national state.(19)

The creation of the Bank of England was also a response to a severe monetary and political crisis. England’s coin was severely debased by the late 17th century, and the outbreak of war with France in 1689 threatened to further diminish the nation’s money supply.

Authorities were in general agreement on the need to call in and remint the nation’s coin, though a lack of consensus over how this should be done produced a vigorous debate in London. Secretary of the Treasury William Lowndes held a modern view of money as simply a unit of account and argued for a recoinage with twenty percent less silver in each coin. Creditors would be repaid with coins containing less silver than was originally contracted, but this was a small price to pay to avoid a drastic fall in the amount of money in circulation.(20)

Locke maintained a traditional belief in rare metals’ “intrinsic value,” and felt that to maintain public trust in the nation’s money and the new bank the state should recoin silver at its original value. His opponents pointed out that returning reminted coins at their face value would drastically reduce the total number in circulation.

Locke’s faction was ultimately victorious, and in early 1696 Parliament passed the Recoinage Act. As the deadline for getting coins to the bank drew near, rumors of insurrection circulated throughout the country. Townspeople rioted in Kendal and Halifax, as did the miners of Derbyshire.

Though fear of generalized upheaval delayed the government’s implementation of the law, the summer recoinage nearly halved the value of England’s coins, with those able to buy up and send silver to the government — landlords, merchants, bankers, tax collectors — benefiting while interest rates skyrocketed and common people unable to sell or send their silver to the mint were left with worthless coins.(21)

Locke also suggested that counterfeiters and coin clippers might be a greater threat to England’s safety than the military might of absolutist France. Another new law, the Coin Act of 1697, made it a capital offense to clip, adulterate, or pass counterfeited money.

To help enforce a law many would view as unduly severe, in 1699 Sir Isaac Newton was named Master of the Mint, a post he held for close to 30 years. The famed scientist was at the time equally famous for his ruthless pursuit of counterfeiters, having established a nationwide network of spies (in which Newton himself reportedly traveled in disguise) to catch those who violated the state’s monetary monopoly. Newton defended his pitiless opposition to mercy for offenders by asserting counterfeiters were incorrigible: “like dogs,” they were “ever ready to return to their vomit.”(22)

By the time of Newton’s retirement Great Britain had become a major global power and England was the richest country in the world. Some scholars have written of a “consumer revolution” in England and British America in the 18th century, as colonial agricultural goods and English manufactures enriched free people on both sides of the Atlantic.

Colonists expressed their identity as Britons largely through the purchase of commodities produced in the metropole.(23) Yet as in England, money scarcity meant that colonial consumption required credit, resulting in unfavorable balances of trade with the home country and widespread debt within the colonies. If anything, money was even more divisive in the Americas.

Making Money in the Americas

Francis Bacon was an investor in the Virginia Company, the joint-stock organization that funded England’s first permanent colony in America in 1607 — the same year, in fact, of the Midlands rebellion that inspired “Of Seditions and Troubles.”

By this time Spain had been plundering the Americas for over a century, killing millions of Native Americans in the process. A century before 1619, when English colonists in Virginia purchased “20 and odd” captive Africans from a passing privateer, Spain and Portugal began forcing enslaved people to their American colonies to labor in silver mines and, increasingly, on plantations.(24)

Since there was no gold or silver in the northern parts of America free of Spanish rule, the English had to look for other sources of profit. They found their cash crop when John Rolfe (husband of the famed Powhatan princess Pocahontas) planted a Trinidadian strain of tobacco in Virginia.

Cultivating tobacco was labor intensive, and the indentured servants from England who constituted the primary workforce in the Chesapeake Bay until the late 17th century were themselves a product of England’s commercial revolution. Indentured servants were required to work in exchange for passage across the Atlantic; the credit relation thus stood at the center of labor in early English America.

In 1623, the indentured servant Richard Frethorne wrote to his parents in London that “there is nothing to be gotten” in Virginia but “sickness and death, except that one had money to lay out in some things for profit.” But Frethorne had “not a penny, nor a penny worth, to help me to either spice or sugar or strong waters, without the which one cannot live here.”

Though he prayed to be “redeemed out of Egypt” — an indication of his slave-like status — the teenaged Frethorne did not survive his American journey.(25) By the second half of the 17th century relatively few English working people were willing to endure bondage in the colonies, a key factor in planters’ turn to captive Africans as a source of labor.

Money remained scarce in English America despite the production of profitable exports like tobacco and sugar, as Parliament prohibited the exportation of silver from England during the economic reforms of the 1690s. Tobacco itself functioned as a form of currency in Virginia and Maryland well into the 18th century, while colonists in New England and New Netherland (New York after 1664) used beaver skins and Native American beads known as wampum for exchange.

However, in 1652 the Boston silversmith John Hull began making local shillings to facilitate trade in clear violation of English law. Counterfeiting rings throughout the Americas were soon manufacturing Hull’s “Boston shillings” as well as Spanish-American pieces of eight — most often from bullion brought to colonial ports by pirates.(26) The use of unofficial money was a foundational, and widely accepted, practice in English America.

While we rightly associate the commodification of labor in this period with the rise of the Atlantic slave trade, the monetization of life was all-encompassing. In the same years that Barbados and Virginia made enslavement a legal status that was permanent and hereditary, a number of colonies instituted forced labor as a form of debt repayment.

In his swashbuckling bestseller The Bucaniers of America (1684), the French pirate Alexander Exquemelin wrote that for debts above 25 shillings the English in Jamaica “do easily sell one another” for a period of forced labor. By the turn of the 18th century, many colonists believed that powerful merchants intentionally kept money scarce in order to dispossess borrowers of their land and labor.(27)

One solution to monetary dearth was simply to create a local medium of exchange. Massachusetts took the major step of issuing public bills of credit in the early 1690s — ostensibly, like the Bank of England, to fund war against the French. A decade later South Carolina printed its own paper money, and soon New York and Rhode Island issued their own currencies.

By the 1710s a number of paper currencies circulated in the colonies; popular almanacs from the era testify to a complex system of intercolonial exchange rates. Both the English crown and wealthy colonists opposed American currencies, however, since “imaginary” paper money challenged imperial authority and reduced the wealth and power of creditors.

Money and Popular Politics

Although tensions between debtors and creditors had shaped social relations in the colonies from their founding, the expansion of print in the 18th century helped make currency a prominent subject of public discussion.

While in the early 1700s a number of northern colonies created paper monies, the Pennsylvania government remained reluctant to issue bills of credit. A major economic slump beginning in 1720 facilitated a decade-long pamphlet war that, in addition to forcing legislators to create a local money supply, uniquely demonstrated popular attitudes to currency.

While learned elites debated issues of sovereignty and economic theory, populist pamphleteers gave literary expression to a widespread belief in local grandees’ self-interested control of the money supply. According to “Roger Plowman,” an allegorical character from an anonymous 1725 pamphlet, city merchants kept currency scarce so they could appropriate debtors’ properties when they were unable to repay loans.

Creditors demanded repayment in money, but when money was not to be found “what must the poor People do?” According to Plowman, merchants like “Robert Rich,” who argued that imaginary paper money would ruin the colony, were worse than ancient Egyptian slave drivers.(28)

One satirical tract had loan bank trustees and local politicians fretting over a new “Democracy in the People” that threatened to eradicate Pennsylvania’s “absolute Aristocracy.” Notably, paper money not only allowed borrowers to repay debts, it also led ordinary people to question the authority of economic and political elites. It was a democratic “Monster” that placed all on a level and therefore needed to be crushed.(29)

The politics of money were not confined to the world of print. In late 1740, Philadelphia merchants decided to devalue the British copper halfpence — a coin crucial for small purchases throughout the colonies. After the extralegal decision was put into force on a frigid January morning, Philadelphians marched through town breaking the windows of traders who refused to accept the pennies at their customary rate. Demonstrators threatened to march again the following night, but authorities managed to suppress the crowd action.(30)

Some months later copies of an anonymously authored broadside (a large single-sided poster) appeared on city trees and buildings. According to “Dick Farmer,” merchants had themselves imported the copper coins to pay farmers, millers and artisans in wages. Yet when people attempted to use the halfpence to purchase goods or repay small debts, the same traders refused to accept them except at the reduced rate.

Farmer implored elected representatives to “rescue the People out of the Merchants’ Power.”(31) Popular discontent continued to simmer after the government failed to act, eventually forcing the Philadelphia municipality to pass an ordinance raising the coin’s value.

A remarkably similar protest occurred in New York City more than a decade later. Meeting at a local coffeehouse in 1753, city merchants agreed that the British copper halfpence was overvalued in New York and should therefore be devalued.

According to “A Citizen” writing in the New-York Weekly Mercury, since money was a matter of public interest, and “any Idiot might know” that most New Yorkers were opposed to devaluation, the secret meeting of self-appointed policymakers was “absurd, inconsistent and ridiculous.”

Like Dick Farmer in Philadelphia, Citizen claimed that it was the same merchants who imported the halfpennies that now refused to accept them. “Is it not strange, that Men who have been the Instruments of importing them, should fall on such Methods to oppress the Public?” Such schemes were, in Citizen’s view, “monstrous, illegal, cruel and inhumane.”(32)

New York nevertheless put the devaluation into effect, sparking coordinated riots throughout the city. Armed with clubs and staves, demonstrators marched through city streets to the beat of a drum, as was customary in popular crowd actions. Authorities were well prepared for the protests, however, as city officials from mayor and aldermen down to sheriffs and constables were mobilized to put down the rising.

A grand jury investigation that placed blame for the protests on impoverished outsiders — “Strangers of the World” — received considerable attention in the press to reinforce an image of law-abiding and respectable New Yorkers.(33) As the Citizen might have noted, however, “any idiot” would have known that there was widespread support for the protestors in the city.

A Liberal Way to Wealth

Max Weber claimed in his classic Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism that the American printer Benjamin Franklin embodied the new 18th-century capitalist ethos. For Weber, Franklin’s value system was characterized not simply by a desire to obtain riches. It was, rather, his association of virtue with proficiency in a specific calling that distinguished capitalism’s “peculiar ethic.” Wealth accumulation was secondary to the individual’s voluntary commitment to professional activity; work was the end, not the means, of the spirit of capitalism.(34)

While Franklin did consistently argue for the virtues of hard work, he also benefited greatly from the era’s financial innovations. In 1729, aged just 23, Franklin published A Modest Inquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency. The essay, strongly influenced by the economic writings of William Petty, argued that an abundant money supply encouraged laboring people to come to Pennsylvania and stimulated economic development.

The following year, the young printer obtained a contract for printing new bills of credit for the colony. Over the course of his career Franklin earned substantial profits from issuing Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey paper money; by the time of his retirement in 1764 he had printed approximately 2,500,000 bills.(35)

Yet Franklin was no monetary populist. Though he carefully cultivated his workingman persona Franklin was, as Weber noted, the embodiment of bourgeois values. Nowhere is this more evident than in the essay The Way to Wealth, which contains classic Franklinian self-help proverbs like “God helps them that help themselves,” and “early to bed, and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.” While full of calls to work hard and use time efficiently, the essay’s overarching emphasis on thrift and frugality primarily concerned the perils of indebtedness.

Set at a merchant’s auction (where many of the goods on offer would have been seized from defaulting debtors), Way to Wealth begins with a popular complaint over heavy taxes. According to the wise old Father Abraham, however, it was idleness, sloth, and a lust for “fineries and knickknacks” that led people into economic trouble, and when you run into debt “you give to another power over your liberty.”

Quoting Proverbs 22:7, Abraham reminded listeners that “the borrower is a slave to the lender, and the debtor to the creditor.”(36) Yet while the biblical verse is a warning to lenders and a plea for the poor, Franklin’s text says nothing about creditors and suggests that borrowers have only themselves to blame for their hardship. Nowhere does Way to Wealth mention debt laws or money supply — subjects that had long animated colonial politics and social conflict.

Franklin took the title of his essay from a sermon by Robert Crowley, a 16th-century printer, clergyman, and social critic. Much as he reversed the meaning of Proverbs 22:7, Franklin inverted Crowley’s Way to Wealth, which was a warning to the powerful not to oppress the poor.

Evoking the voice of a plebeian participant in the massive anti-enclosure rising of 1548 known as Kett’s Rebellion, Crowley claimed that the revolt was caused by “greedy cormorants” who “take our houses” and “buy our grounds out of our hands,” who “raise our rents,” “levy great (yea unreasonable) fines,” and “enclose our commons!” Since the rich had reduced common people to a state of slavery by monopolizing resources, working people had no choice but to resist with force.(37)

For Franklin, by contrast, the cause of people’s loss of freedom was their imprudent desire for luxuries. The power of the creditor over the debtor need not be regulated by social norms; it was a contractual affair in which the lender’s denial of liberty to the borrower was right and just.

Despite the efforts of classical liberals like Franklin to depoliticize debt and money, currency would remain a source of contestation in the age of the American Revolution. James Madison argued in Federalist No. 10 that republics were preferable to democracies mainly because in democracies the people could more easily demand economic equality.

In the context of the 1780s, popular demands included a “rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts,” and even “for an equal division of property.” The U.S. Constitution, authored primarily by Madison, attempted to eradicate the possibility of such “wicked projects” in the future.(38)

Towards a Monetary Movement Culture?

In his classic book on the American Populists, Lawrence Goodwyn claimed that successful mass democratic movements require the creation of a “movement culture” — a bottom-up movement of activism, education, and solidarity.(39)

Money figured prominently in the demands of the Populists’ movement culture, which culminated in the creation of the People’s Party in the early 1890s. The party’s Omaha Platform of 1892 attacked bondholders who had appropriated the national power to create money, and called for — in addition to the unification of the country’s labor forces and the nationalization of the railroads — a “just, equitable, and efficient” monetary system. This involved an expanded money supply, a graduated income tax, postal savings banks, and keeping the nation’s money “in the hands of the people.”(40)

It is difficult to imagine a social movement today making similar demands. Modern Monetary Theory has provided an important counter to neoliberal monetary orthodoxy. MMT economists have had relatively little to say about democracy, however, and the theory admittedly does not apply to countries that do not issue their own money (for example those in the eurozone) or who remain under U.S. dollar hegemony.

Moreover, a key danger today, in the midst of inflation and the Fed’s raising interest rates and facilitating a recession, is that money will again be depoliticized in the interests of “fiscal discipline.” Monetary policy remains, as Samir Sonti has concisely put it, “a blunt weapon of class warfare.”(41)

Advocates of heterodox economic theories and progressive policies like participatory budgeting and public banking, as well as supporters of the abolition of student and other kinds of debt, would do well to explore the rich history of monetary politics.

In much the same way that the study of preindustrial social relations helps to denaturalize wage labor, knowledge of money’s long history helps us think beyond our current limited horizons of the economically possible. Money, as the early moderns knew, was a social construct that could serve disparate interests. A similar awareness might help us demand that the muck be spread more equitably today.

Notes

- Francis Bacon, “Of Seditions and Troubles,” in Bacon, The Major Works (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 369.

back to text - See, for example, Dave Denison, “The Money Printers,” The Baffler no. 52 (July 2020).

back to text - A recent MMT bestseller is Stephanie Kelton, The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and How to Build a Better Economy (London: John Murray, 2020). For a critique of MMT from the left see Michael Roberts, “Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique,” Class, Race, and Corporate Power 7, no. 1 (2019), Article 1.

back to text - David McNally’s Blood and Money: War, Slavery, Finance, and Empire (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020).

back to text - Philipp Caesar, A General Discourse Against the Damnable Sect of Usurers (London, 1578), 6-7, 13-15.

back to text - Andy Wood, Riot, Rebellion, and Popular Politics in Early Modern England (New York: Palgrave, 2002).

back to text - Thomas More, Utopia, in Stephen Greenblatt et al., eds., The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume 1 (New York: Norton, 2006), 531, 557-58.

back to text - For popular risings in Tudor England see Anthony Fletcher and Diarmaid MacCulloch, Tudor Rebellions, 5th ed. (New York: Pearson Education, 2008).

back to text - Tim Stretton, “Written Obligations, Litigation and Neighbourliness, 1580-1680,” in Steve Hindle, Alexandra Shepard, and John Walter, eds., Remaking English Society: Social Relations and Social Change in Early Modern England (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 2013), 189-209.

back to text - Craig Muldrew, “‘Hard Food for Midas’: Cash and Its Social Value in Early Modern England,” Past and Present No. 170 (February 2001): 113-17.

back to text - John Taylor, A Shillling; Or, the Travailes of Twelve-Pence (London, 1621).

back to text - Deborah Valenze, The Social Life of Money in the English Past (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 38.

back to text - Malcolm Gaskill, Crime and Mentalities in Early Modern England (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 126-34.

back to text - Craig Muldrew, “From Commonwealth to Public Opulence: The Redefinition of Wealth and Government in Early Modern Britain,” Remaking English Society, 317-39.

back to text - William Petty, Several Essay in Political Arithmetick (London, 1690).

back to text - Bernard Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees and Other Writings (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1997), 19.

back to text - Mandeville, Fable of the Bees, 70-71, 122.

back to text - C.B. Macpherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962), 203-9.

back to text - McNally, Blood and Money, 131; Christine Desan, Making Money: Coin, Currency, and the Coming of Capitalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), Chapter 8.

back to text - Carl Wennerlind, Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution, 1620-1720 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011), 129-30.

back to text - Muldrew, “‘Hard Food for Midas’,” 107-8.

back to text - Wennerlind, Casualties of Credit, 146-49.

back to text - Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Vintage Books, 1993).

back to text - Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern (New York: Verso Books, 1997).

back to text - “Richard Frethorne, to His Parents (Virginia 1623),” in Paul Lauter et al, eds., The Heath Anthology of American Literature, 5th ed. (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company), Volume A, 270-71.

back to text - Mark G. Hanna, Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570-1740 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 96.

back to text - Alexander O. Exquemelin, Bucaniers of America: Or, a True Account of the Most Remarkable Assaults Committed of late Years upon the Coasts of the West-Indies, 2nd ed. (London, 1684), 38; Daniel Johnson, “‘Nothing will satisfy you but money’: Debt, Freedom, and the Mid-Atlantic Culture of Money, 1670-1764,” Early American Studies 19, no. 1 (Winter 2021): 103-4, 110-11.

back to text - A Dialogue Between Mr. Robert Rich and Roger Plowman (Philadelphia, 1725).

back to text - The Triumvirate of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, 1725).

back to text - Johnson, “‘Nothing will satisfy you but money’,” 131.

back to text - Ibid., 132.

back to text - New-York Weekly Mercury, January 7, 1754.

back to text - Johnson, “‘Nothing will satisfy you but money’,” 132-34.

back to text - Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Dover, 2003), Chapter 2.

back to text - Eric P. Newman, “Franklin Making Money More Plentiful,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115, no. 5 (October 1971): 341.

back to text - Benjamin Franklin, The Way to Wealth, reprinted in Heath Anthology of American Literature, Volume A, 809-11.

back to text - “Selections from the writings of Robert Crowley,” in C.H. Williams, ed., English Historical Documents: 1485-1558 (New York: Routledge, 1967), 303-4.

back to text - James Madison, Federalist No. 10, The Federalist Papers, available online at https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/full-text.

back to text - Lawrence Goodwyn, The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

back to text - The “Omaha Platform” of the People’s Party (1892), in The American Yawp Reader: A Documentary Companion to the American Yawp, Volume 2 (Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University Press, 2019), 18-22.

back to text - Samir Sonti, “Inflation and Your Next Union Contract,” Labor Notes, July 8, 2022.

back to text

September-October 2022, ATC 220