Against the Current, No. 219, July/August 2022

-

The Rightwing's Supreme Court Coup

— The Editors -

Assange, Donziger and the DNC Media

— Cliff Conner -

A Letter from California's Death Row

— Kevin Cooper -

COVID & the Global South: the Nigerian Case

— Emilia Micunovic -

Ukrainian Leftist Speaks

— an interview with Taras Bilous -

After Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

— Ashley Smith -

The Murder of Shireen Abu-Akleh

— David Finkel - The Case of Derrick Jordan

- Struggle in the University

-

The Competence Curse

— Purnima Bose -

Faculty Governance in Academia

— Eva Cherniavsky -

Renewal of Shared Governance?

— Benjamin Robinson - Revolutionary Experience

-

An Introduction, A Conclusion

— The Editors -

To the Working Class, 1969-1980

— Dan La Botz -

Field Work

— Sam Friedman - Reviews

-

Migration Politics and Criminalization

— Cynthia Wright -

Disability Studies from South to North

— Owólabi Aboyade (William Copeland) -

Mass Misery, Mass Addiction

— Dave Hazzan -

A Giant Rescued from Oblivion

— John Woodford -

Three Mothers Who Shaped a Nation

— Malik Miah -

The High Price of Delusion

— Guy Miller - In Memoriam

-

Oscar Paskal, 1920-2022

— Nancy Brigham

Dan La Botz

IN 1969, THE International Socialists, of which I was a member, started a national discussion about how to move toward the working class. Our collective discussion, carried out over a couple of years in the IS discussion bulletins, convinced many of us that the only way to reach the American workers was to go to work, to get a job.

The years 1968 to 1971 saw some of the biggest labor movements and strikes in U.S. history. The Black Lung Movement and Miners for Democracy struggled to overthrow the corrupt machine of Tony Boyle. In the auto plants, African American workers created rank-and-file shop-floor organizations and union reform groups such as the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers to fight both company and union racism.

Telephone workers in New York engaged in a weeks-long strike. Steel haulers in Illinois, Indiana and Ohio created the Fraternal Association of Steel Haulers (FASH) to fight both employers and the Teamsters union bureaucracy. Other Teamsters rank-and-file truck drivers and dockworkers established Teamsters United Rank and File (TURF) to fight for better pensions and to reform the union.

We in the IS decided that what made most sense was to seek work in jobs, plants, companies, cities, industries and unions that had a strategic role in the American economy as well as a history of struggle. We began to come up with a list of target industries: mining, steel, auto, telephone and trucking. Beginning in 1970, many of the 300 IS members began the move from campuses to big cities, mostly in the Midwest, and to take jobs in heavy industry.

We chose the traditional industries like steel and auto over services or the public sector. While many of us had had wonderful educations and had dedicated ourselves to studying the economy, society and politics, we did not foresee at all that we were moving toward the past rather than the future.

While we were moving toward the Midwest, the nation’s population and industry were moving toward the West and South. Capital was pouring into new industries in what would become the microchip, the computer, and new wireless telecommunications sectors. The world was being drawn into a new global economy.

As the nation headed toward the conservative 1980s, we were attempting to move back to the social upheaval of the 1930s. We would not awaken to these problems until the 1990s.

Getting Industrial Jobs

We called this program “industrialization,” meaning we were getting jobs in industry. We intentionally promoted industrial work over jobs such as teaching or social work in which some of our members, myself included, had been involved. We had made this decision collectively and democratically, and now we attempted to implement it through peer pressure.

We urged our members in those white-collar professions to quit and get a job in auto, steel, telephone or trucking. In retrospect, we may wonder if this was the right decision. Should we have attempted to build a political organization with a broader conception of the working class? Yet if we had not taken jobs in industry, could we ever have had the same impact that we did?

The first task was to get a job. In Chicago, where I had gone, one member headed up our socialist employment agency. He analyzed industries, companies and particular plants. He studied the unions, their histories, their current officers, their finances and their membership.

Our comrade made lists of likely areas and companies where our members might find work and sent us out to apply. He explained how we could create phony work records so people would hire us — no one wanted to hire a graduate of UC Berkeley or the University of Chicago to work in a steel mill or to drive a truck. He created names, phone numbers and letterhead for the fictitious companies and became the person who answered the phone to confirm our phony work records.

Within a year or two, we had a few members working at U.S. Steel South Works who became members of the United Steelworkers. We had a couple of members at an International Harvester plant represented by United Auto Workers Local 6. We had one member working at Illinois Bell Telephone Company who became a member of the Communications Workers of America.

Later we would have members, I was one of those, in a few trucking companies who became members of the Teamsters. Our members began to join in shop floor struggles and to participate in union meetings. The rhythms of contract negotiations and union elections soon came to set the pace for the work of our branch.

Within a couple of years, we had made the transition from a student organization involved mostly in the antiwar movement to a socialist organization made up of déclassé members active in the working class — which was not to say that we had become a working-class organization.

In the mid-1970s, we had a discussion about whether we should have separate priorities for our women members. Should they seek jobs in male-dominated industries and attempt to become activists and leaders there among a mostly male workforce, or should they seek jobs where most workers were women, so they could become women leaders of women?

We all considered ourselves feminists by that point, and a feminist could make a good argument for either position. Women would be most effective as leaders of women perhaps, but they should not hesitate to become leaders of men either. In the end, we decided that male and female members should seek jobs in the same heavy industries.

So we had women members who became telephone operators, but also auto workers, steel workers, truck drivers and dock workers. And many of them did become leaders of the small groups of women in those industries, and sometimes leaders, as well, of the male workers in their plants or unions.

All that was admirable, but at the same time there was a price to pay by working in the industrial unions. Women in our organization became separated from broader currents of feminism in society and from working women’s organizations, such as the new 9-to-5 union that developed outside of industry among Chicago’s female office workers.

I Become a Truck Driver

In 1974, I was living in a low-income neighborhood in Chicago. I attended truck-driving school paid for by a federal anti-poverty program and became a qualified truck driver. My goal was to get hired into a large trucking company that would be represented by one of the major Chicago freight locals: Teamsters Local 710 or Local 705, or the Chicago Truck Drivers Union (Independent).

I put in applications at all the big companies where the IS was attempting to get people hired: Roadway, Yellow Freight, and Consolidated Freightways. While waiting to hear from them, we also went and applied at local cartage companies, and, as it happened, one of them was hiring.

Workers at F. Landon Cartage were represented by the Chicago Truck Drivers Union (Independent), a union that was not part of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters but was covered by the Chicago Teamsters agreement, which paralleled the national freight contract that covered most companies.

I worked at Landon for the next three years, from October 1975 to the end of 1978 and later, for a few more years, at other trucking companies. I had gotten the job at Landon in order to be an activist in the Teamsters union, but Landon Cartage’s drivers and dockworkers would never form a base for such activities.

The workers, if not exactly delighted with their jobs, were not highly dissatisfied either. Mostly men with a high school education or less, they held a union job that paid a relatively high wage, about $12 an hour, and usually got about 10 hours of overtime (sometimes more) each week paid at time and a half. The employer did not treat us badly — in fact, a driver’s job was easy; no doubt a dockworker’s job was harder.

If a worker had a problem, the union would usually intervene and save the worker’s job, unless he had been caught red-handed drunk, fighting or stealing. Few were caught red-handed.

Working at F. Landon Cartage must have been one of the best jobs in the trucking business in the city, though it was not completely out of the ordinary. The trucking industry, which began as a competitive and cutthroat business in the 1930s, had been brought under Federal regulation in the 1930s, controlling new entrants, establishing routes and rates.

The Teamsters union in the period between 1934 and 1964 had through a series of strikes brought the industry under the National Master Freight Agreement (NMFA), a pattern agreement covering most companies and workers. Between Federal regulation and the union, employers secured their profits and the union protected the workers’ jobs and wages.

Just as I entered the industry in the 1970s, employers began to try to change the thirty-year old system. First, they pushed for greater productivity from dockworkers and drivers and then they pushed to dismantle or to escape from the NMFA.

Later Congress passed deregulation, which dismantled the whole system. Before all that, however, when I went to work as a driver, for the most part jobs were secure, wages high and conditions pretty good. But things were changing at the cross-country freight lines.

During the 1960s and 1970s regional companies had merged into national freight lines such as Roadway, Yellow, and Consolidated Freightways. Those companies were making the big push for productivity. United Parcel Service, the package delivery company, had developed intense supervision methods and high productivity demands that the others began to emulate.

All the national companies were trying to get Teamsters to work faster and move more freight. Regional carriers found themselves in competition and adopted the same strategy. My impression is that such pressure hadn’t at that time worked itself down to the smaller, local cartage, drayage or haulage companies. Later, however, some would be driven out of business by the more efficient regional and national carriers.

The base of the movement we were organizing would be the dockworkers and drivers at the larger companies, workers who were feeling the pressure from employers for productivity and profits.

The Chicago Truck Drivers Union

The Chicago Truck Drivers Union, to which I belonged, was a very strange union in many ways. In the early years of the Teamsters, around the year 1905, several Chicago Teamsters locals, disappointed by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) failure to support a Chicago strike, left the union and became independent.

Later during the Prohibition era, many Teamsters union locals fell under the control of the Mafia, which took control of the trucking industry in order to move illegal booze. Several of the Mafia-dominated Chicago Teamsters locals left the International Brotherhood of Teamsters during that era.

In 1933, pressured by local business interests tired of dealing with extortion by violent crooks, the government decided to get rid of the mob. Chicago Mayor Edward J. Kelly and Illinois State’s Attorney Thomas J. Courtney, working with John Fitzpatrick and Edward Nockels, progressive leaders of the Chicago Federation of Labor, and with Teamster President Dan Tobin, joined together to force the Mafia out of the Chicago Teamsters and bring the local unions back into the IBT and the American Federation of Labor.

One of the Chicago Truck Drivers Unions, however, remained independent under autocratic leadership. After the mob assassinated the former president Mickey Galvin in 1936, Edward Fenner became the head of the union with a title unknown in the regular Teamsters unions, “executive director.”

The union under Fenner was not mobbed up, but it did not hold monthly union meetings like other unions but called a meeting only once every three years to announce the terms of the new contract. The union had no union hall, but rather an office over a bank on the corner of Halsted and Madison.

There was no union newspaper, no union mailings, no union literature whatsoever. Fenner and the other business agents — wearing three-piece suits, homburg hats, and dark overcoats in the winter — were all chauffeured around in big black Buicks. They looked more like a crew of funeral directors than union representatives.

Local Caucuses

The IS had developed the strategy of attempting to create reform caucuses in the unions where we had become involved. In each of the cities where we worked, we attempted to find local activists who had been involved in fighting the companies and the union bureaucracy and to form an alliance with them.

We always had the sense of a symbiotic relationship between ourselves as radicals entering the working class and Teamster activists who had been there, often for decades.

We believed that we had things to communicate to workers about U.S. imperialism, American politics, capitalism, and the struggle for socialism. We also had skills we had learned in the civil rights and anti-war movements, skills as organizers, writers and speakers. We knew how to design and print a leaflet or a newspaper.

We recognized that they too had things to teach us. They understood the local employers, the union, and the mentalities of their co-workers far better than we possibly could. As we shared our perspectives and information, we influenced one another.

Once we had reached agreement with the Teamster activists on some local goals and objectives, we began to organize by publishing an opposition newspaper in each locality. By early 1976 we had local groups in Seattle, Los Angeles, Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh and New York, and later we added a few others.

Each of those groups put out a monthly local newspaper discussing problems in the companies and in the union. By 1976 we must have had 25 members working as Teamsters in about seven or eight cities, a very small group but with a strategic placement in important companies and local unions.

Those members had established close working relationships with other Teamster activists with whom they had come to agreement on the need for reform in the union. What we needed now was the courage and commitment, the discipline and energy to try organizing something big.

A National Rank-and-File Movement

In 1975 we first attempted to use our socialist politics and our strategic ideas to set this large-scale project in motion. Rather like using a series of pulleys to lift a heavy object, the tiny IS, an organization of a few hundred, would build and lead caucuses that numbered in the hundreds or thousands, which could in turn move the unions, whose membership numbered in millions.

What we called “class struggle unionism” could influence tens of millions of others in the working class. With this block-and-tackle conception, our efforts would be multiplied a thousand-fold.

We aimed to establish a class-struggle pole, and in fighting for reforms, to set millions of workers in motion against their employers. We foresaw reform caucuses taking power in those major industrial unions, transforming the AFL-CIO and eventually reaching unorganized workers as well.

In doing so we hoped to create a new sense of workers’ power in American society, a power that would move America to the left.

To do this, we had to overcome an enormous obstacle. We understood that U.S. labor unions were highly bureaucratic and conservative; that is, the character and structure of the union officialdom had become solid defenders of the capitalist status quo and an obstacle to workers’ interests and struggles.

The character of the labor bureaucracy was clear to see: union officials were a caste apart. They received high salaries, often many times those of an ordinary worker. In the Teamsters union they reached $500,000 when an ordinary dockworker, driver or factory worker made $30,000.

Union officials also had expense accounts that covered their hotel bills, meals, even bar tabs. Officers at the highest levels had perquisites such as the union jet (the Teamsters had a small fleet of planes), and even low-level officials had union cars. In the Teamsters union the officials wore expensive suits and topcoats, drove Buicks, and some flashed diamond pinky rings.

Perhaps most important, most union officials had become lifetime career bureaucrats; they no longer drove trucks, loaded freight on the docks, or worked in a factory like other workers. When they retired, or if voted out of office, few indeed were the officials who returned to work. Often they took jobs with management or with a labor mediation agency or opened their own business, sometimes even setting up non-union businesses in the industries where they had formerly been union reps.

Virtually all union officials held to a view we could call “business unionism,” that is, that the job of the union was to support business and that the union itself should be run along business lines. The corporate structure of American capitalism was replicated in the hierarchy and the top-down, vertical control found in most unions.

The industrial unions also reproduced the race and gender patterns of American business institutions and society more generally, with white men heading the unions and African Americans, Latinos and women having very small roles. Many AFL craft unions still excluded African American, Latino and women members, and when forced by lawsuits or government regulations to admit them, made the newcomers’ lives unbearable and sometimes drove them out of the union.

Bureaucratic Union Caste Ideology

Union officials held their own caste ideology, that they were the best guardians of the workers’ interests. While the UAW and other former CIO unions supported the civil rights movement and the women’s movement, they often ignored the problems of workers in their own unions.

So, for decades the union negotiated higher wages and better benefits but ignored the workers’ demands to slow down the speed of the production line, to improve conditions on the shop floor, and for bosses to treat workers with dignity. Leaders of these unions saw themselves as speaking for the workers — but would not let the workers speak for themselves.

Other union leaders, the typical union officials without a leftist history, generally accepted the capitalist ideology and argued that what was good for the company was good for the workers. If the company was successful, i.e. profitable, the union could pressure the company to share some of that profit with the workers. The union’s job then was to see that workers didn’t interfere with the company’s production and profits.

Whether Republicans or Democrats — or the rare social democrat — many union officials came to see their role as policing the contract for the company. Above all, company managers and union officials collaborated to prevent workers from engaging in slowdowns, work stoppages and strikes.

In the worst of cases at that time, officials of the Teamsters, the Laborers, the East Coast Longshoremen’s union (ILA), the Hotel and Restaurant Workers and the National Maritime Union were in some cases actually members of the Mafia. They saw the union as their property, a machine for criminal activities.

These union officials used the power of the union to extort money from both businessmen and workers. They took labor peace payoffs, that is, they took money in exchange for accepting a contract and preventing a strike.

Some literally sold jobs to workers and took payoffs from workers to keep those jobs. They controlled crime and contraband in the workplace or the job site, sometimes promoting gambling, prostitution and drugs at work.

Whether leftist, business unionist, or corrupt, union officials generally viewed workers as subordinates who had to be controlled. Workers speaking out or standing up for their rights were viewed as “troublemakers,” and management and the union often colluded to fire them and sometimes blacklist them in the industry.

In the more corrupt unions, the gangster union leaders beat workers and even occasionally murdered them — though by the 1970s the murders were rare.

Within the unions, our job would be to organize rank and file workers first to take over leadership of the union and then to fight the employers, and while doing that, we hoped to recruit the leaders of the movement to socialism.

We believed that workers — particularly the more active workers, such as union stewards — would be attracted to the rank-and-file groups we helped to create. We would then recruit the most political of those rank-and-file activists to our politics and organization, transforming the IS in the process to become a genuinely working class group.

We envisioned growing from a few hundred to a few thousand and, within a decade or so, to a socialist group of perhaps 10,000 — what we called a “small mass party.” We wanted to strengthen workers and the unions, but our goal was never simply union reform or winning a better contract.

The goal was to build a revolutionary socialist party that could play a leading role in the overthrow of American capitalism and in bringing about the establishment of a democratic socialist society. Our conception of socialist revolution derived above all from the experience of the Russian Revolution of October 1917, that a disciplined revolutionary party could lead a mass workers’ movement in overthrowing the capitalist state and establishing working class power.

The Organization of TDC

The next step after creating local caucuses was to bring all of these local groups into contact with one another, to launch a campaign around the national freight contract. In a preliminary step, we began to organize trips with Chicago Teamster activists to visit similar groups in Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

Workers felt stronger being part of the opposition if they knew there were others like themselves out there. At the same time, these trips drew us closer to the people we worked with locally, so that we became part of a team.

Our Teamster “fraction,” that is the IS members in the Teamsters union, created a national steering committee and we circulated a Teamster fraction bulletin with information on what was happening nationally and in the cities where we worked. Between 1970 and 1974, the steering committee called occasional meetings of our Teamster members on the West Coast and in the Midwest to discuss developments and strategy.

This circulation of information and discussion helped to create a common understanding, to develop a common analysis of the industry and the union, and made our members more effective in their work with other Teamsters. Joining with other Teamsters in various regions, we launched a national contract campaign in 1974 that adopted the name Teamsters for a Decent Contract, or TDC.

During the course of many meetings and discussions, the IS arrived at a consensus about our general organizing strategy. The synergy of the interaction between IS members and Teamsters would be essential to the success of the movement. While we were socialists, we were not attempting to create a socialist movement of Teamsters. Clearly in the United States at that time, few truck drivers and dockworkers had any interest in socialism and many were anti-Communist.

We aimed, rather, to build a rank-and-file workers’ movement that could push the Teamsters union to strike against the employers. In this way we would demonstrate the power of the rank-and-file and draw more Teamsters into the struggle, while at the same time introducing them to our socialist politics.

We were clear that for the time being, we only wanted this to be a contract movement, not yet a general reform movement. We had to restrain (but not for long) some of our co-thinkers, who wanted to leap immediately into a full-scale battle to change the union.

From TDC to TDU

Under pressure from TDC’s “no contract, no work” movement, IBT president Fitzsimmons was obliged to call an official strike that lasted three days. TDC activists and members of the sister group of UPS workers, UPSurge, led wildcat strikes at freight terminals in Detroit, and briefly at UPS terminals in eight cities in the Central States region.

It was the first national IBT strike in freight, and it secured for the members a significantly improved contract.

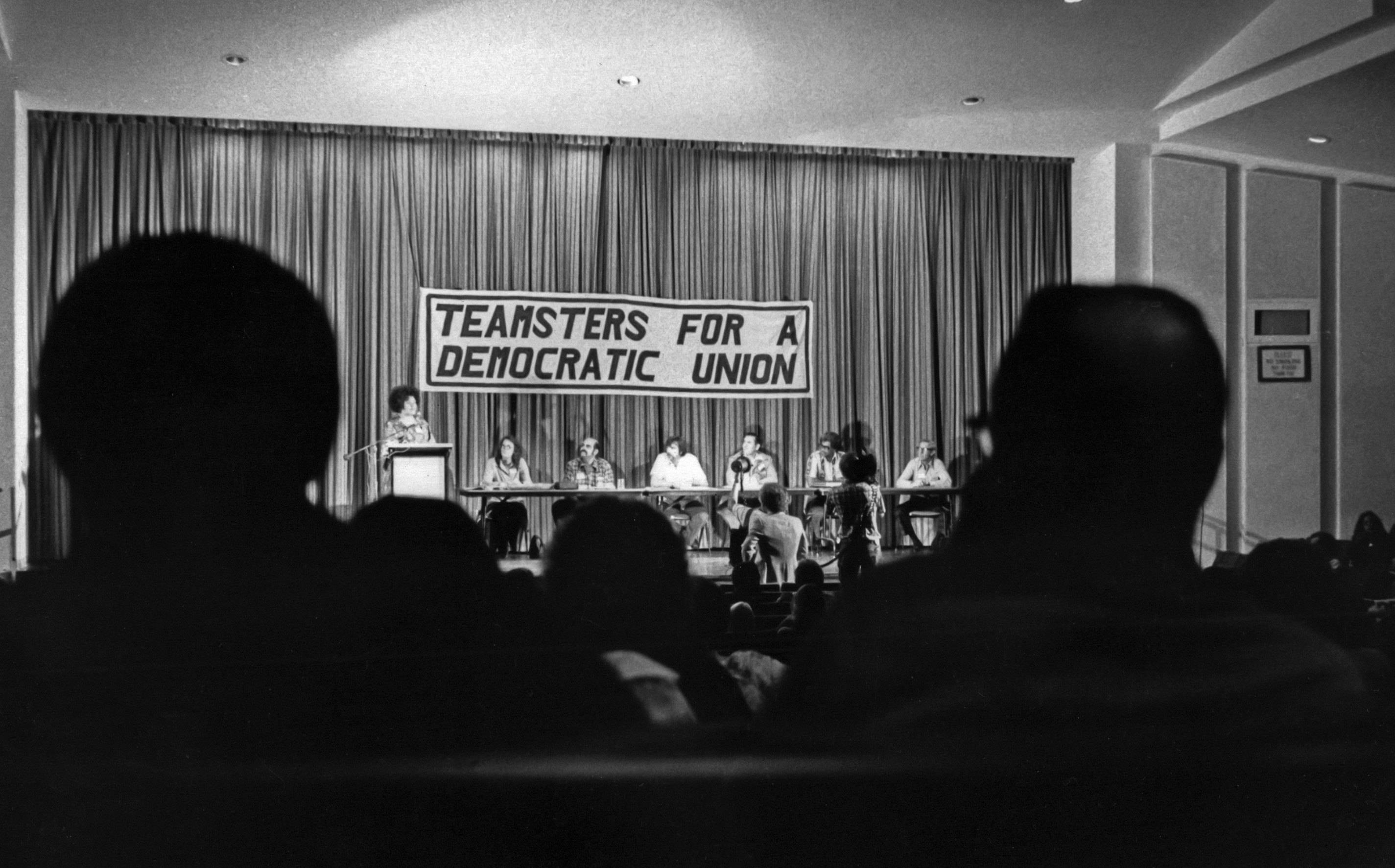

During the TDC contract campaign, we had begun to make plans to found a permanent national opposition group within the union. Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) held its founding convention on September 18, 1976 at Kent State University in Ohio. In attendance were about 200 rank-and-file Teamsters, from 44 local unions and 15 states.

TDU was created as a rank-and-file group focusing on the issue of union democracy. Although coming as it did out of a national contract campaign and a series of wildcat strikes, it was clear that the goal of the group was to transform the Teamsters into a more militant and powerful union.

When time came to elect a national steering committee, we in the IS adopted a policy that this should be an organization led by Teamster activists, not primarily by IS members. From the beginning we decided that while a few of our IS members would play leading roles in TDU, we wanted grassroots Teamsters from around the country to make up the majority of the movement’s leadership.

We rejected the idea of fighting to get a majority of our members on the TDU steering committee. We needed just a few IS members in the leadership so that we could participate in a discussion with rank-and-file leaders about how to carry the movement forward. They were, after all, the ones in touch with the rank and file.

We also worked to nominate a committee that would include not only white male workers, who had historically dominated the Teamsters union, but also African Americans and women who had generally been excluded in the past.

The TDU founding convention adopted as its central campaign a fight for union bylaws reform that would allow members to elect stewards and business agents. We believed that this kind of reform would unleash the power of the rank and file. Ken Paff, who had organized TDC, was chosen by the Convention and the new Steering Committee as the national organizer for TDU.

Socialism in the Labor Movement

While organizing the Teamster reform movement, we were also trying to win individual Teamsters to socialism. First, we attempted to explain our socialist views and our membership in the IS to our closest collaborators. Second, when we had national TDU steering committee meetings or TDU conventions, we would schedule parallel private meetings with TDU leaders and activists to talk about the IS and socialism.

These meetings served three purposes. By explaining our socialist identity, strategy and goals, we anticipated and prevented redbaiting. If someone accused us of being socialists, our friends would say, “Sure, we know. They told us. So what?”

These private gatherings also allowed us to discuss long-term strategy for the rank-and-file movement with our closest collaborators in a way we could not necessarily do in TDU steering committee. Finally, they also made it possible for us to raise the idea of some of these Teamster activists joining the IS.

In addition to this personal work with specific Teamsters, we had more general work with the Teamster activists at large. The IS published a socialist newspaper, written in accessible language, called Workers Power, which regularly featured articles about the Teamsters and TDU, as well as all sorts of other labor union and political news.

Workers Power also covered the African-American movement and African liberation struggles as well as the radical labor movement in Southern Europe. IS members sold our paper at selected workplaces. For a few years I sold regularly at the main Post Office in Chicago, often at the change of shift at midnight. Other members sold the paper outside Teamster workplaces.

IS Teamster members also sold Workers Power to the Teamsters with whom we worked. In some workplaces we had regular Teamster readers who looked forward to reading our paper. Workers Power occasionally interviewed our “open” or “public” socialist Teamster and TDU activists and leaders, or quoted them in articles on the TDU and the IBT.

Finally, the IS distributed pamphlets such as Building the Revolutionary Party, Class Struggle Unionism and a pamphlet I authored, Conspiracy in the Trucking Industry. At times, our role as TDU activists and socialist propagandists became hard to keep separate.

At Landon where I worked, I distributed our local paper The Grapevine, the TDU national paper Convoy, and the IS paper Workers Power. Even though Landon was a very conservative workplace, all the workers always took the first two, which were free, and a few always bought Workers Power.

Some of the dockworkers and drivers found my constant propaganda and agitation bizarre and amusing. One day when I arrived at work someone shouted, “Here comes the paper boy!”

Through this variety of efforts, during the period from about 1975 to about 1979, the IS managed to recruit about 20 Teamsters. The Teamsters who joined included rank-and-file activists and local TDU and Teamster leaders from three or four different cities.

Most of the IS Teamster recruits, with a few exceptions, were rank-and-file TDU activists who had been won over to the IS because they were impressed with our strategies and our commitment, and were therefore open to our politics. If socialism made people better fighters for union democracy and justice in the workplace, then they were eager to join up with the socialists — even if they didn’t understand exactly what socialism meant.

Most of these recruits did not become well integrated into our organization and their relationship to the IS remained tenuous. The principal reason for this was the great difference between the personal and social lives of the IS members and the Teamster rank and filers.

For our younger members, their whole life was their involvement in the socialist organization and politics; most rank-and-file Teamsters, however, had responsibilities to family, community and church. Our attempt to bridge these different worlds failed partly for lack of a big enough movement that might have connected them.

Another failing was that we never established a real educational program to teach these workers about our politics, nor did we have very good educational materials for workers about the basics of socialist theory, politics, economics and unionism.

At the time, however, we did not yet see and understand these difficulties. We were proud to have some real workers in the organization. We felt we had made a breakthrough; a working-class organization in theory, we were about to become one in fact.

Crisis in the IS

We did not realize it at the time, but our success in launching a national reform organization in the Teamsters took place at just the moment that the great wave of working-class activism that had begun in the late 1960s was coming to an end.

Several factors had converged to create the labor upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s that took place among public employees, farm workers, Black autoworkers, telephone and postal workers. The most important of those factors had been the national legitimization of social protest as a result of the African-American civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War movements.

Protest became an American way of life for 30 years, and many American workers took up the picket sign and joined the strike. Inflation and the employers’ push for higher productivity both affected workers’ consciousness, leading many workers to strike to resist speedups and to fight for higher wages.

Taken together, these social and economic factors had generated a new working-class consciousness, one that led many workers to become not only more militant but also in some cases more radical.

Then, between 1975 and 1980, militant working-class struggle in the United States virtually crashed (with some exceptions such as the 1978 miners’ strike), in part because the factors that had nurtured it — such as the Civil Rights and antiwar movements —themselves declined.

Most important for the labor movement, though, were the two devastating recessions of 1974-75 and 1979-81. In the 1974-75 “stagflation” recession, unemployment reached 10 percent for the first time since the Great Depression. In the wake of each recession came bankruptcies and the beginning of what came to be called “deindustrialization,” the shutdown of many older industrial plants, particularly auto factories and steel mills.

Hundreds of thousands of workers in heavy industry lost their jobs, their union jobs. With the recessions and the plant closings, workers became afraid to fight. The era of strikes that had begun in the mid-1960s wound down in the late 1970s and was all over by 1980.

We didn’t fully understand what was happening at the time. If we thought that we had only entered the doldrums, in reality we were in the Bermuda Triangle. Our entire political strategy was predicated upon involving ourselves in workers’ struggles in unions in heavy industry — and now heavy industry began to close down, even be torn down.

Unions began to shrink; workers ceased to struggle. Throughout the Northeast and the Midwest, and in other regions of the country, industrial workplaces closed. As social movements declined and labor went into retreat, conservative political organizations began to become more influential.

For the decade from 1968 to 1978 we had been swimming with the stream; after 1978 we were going against the current although, as I say, we weren’t aware of all of this at the time, and what had happened would only become clear as we moved on into the 1980s.

Nevertheless, whether we were aware or not, those developments contributed to the crisis that was to practically blow apart the IS.

Factionalism Cripples the Group

Around 1976, a group of members had become critical of the IS industrial-organizing strategy. They believed that an organization as small as the IS, which was throwing itself into union reform work, would inevitably be led to give up its revolutionary politics and become a reformist organization.

They objected to industrial priorities, to students becoming industrial workers, to IS worker-activists running for union office. Believing that the organization was heading down the wrong track, they decided to organize an opposition.

Leaders of this group traveled to Great Britain and met with leaders of the British Socialist Workers Party (SWP, formerly the British IS). There they proposed the initially secret creation of a faction within the American IS that would be loyal to the British leadership. They returned to publish a document called “The New Course” and used it as the political basis to create a tendency called the Left Faction.

Their document they argued that the IS had become depoliticized and that it was necessary to put politics back into the organization. In reality, these folks wanted to return to being a socialist propaganda group rather than a socialist group that sought to organize and lead working-class struggles.

They believed that during what would be a long period of “downturn,” as they called it, IS members should go into professions like teaching, and the organization should reorient to college campuses to recruit students to socialism.

The Left Faction was pitted against the IS leadership. As often happens in such cases, the opening up of the faction fight led to the rise of a third group, the Political Solutions Caucus. The PSC wanted to stick with industrialization, industrial priorities and attempts to lead mass work, but also wanted to fight what it too saw as the depoliticization of the IS.

At the March 1977 convention, the IS majority leadership succeeded in winning enough delegates to expel the LF for having formed a secret faction. As a result, the IS was reduced from about 300 to about 200 members. Within a year or so, the PSC also left, taking with it a few score members.

By 1979 the IS “majority” had been reduced to a little over 100 members, many of them in industry, but with an organization so battered and weakened as to be much less effective. Moreover, as described above and with the election of Ronald Reagan on the horizon, the political situation in the country and in the labor movement was deteriorating at a rapid rate. (One positive side was a decision at the 1978 IS convention to launch what became the Labor Notes project.)

We would have hard times ahead. That was true not only for the IS — which joined with other groups in 1986 to form Solidarity – but for the entire labor-oriented and socialist U.S. left. Those years would open a new period for U.S. labor and the left, all the way to the events of the present.

July-August 2022, ATC 219

Interesting and helpful article. I was part of a different current of leftwing labor organizing, that of the CPUSA. I was a rank-and-filer in the USWA and the UE. My main contribution was as editor of LABOR TODAY. LT was affiliated with the National Coordinating Committee for Trade Union Action and Democracy. There were rank and file groups in a number of unions. You can find an assortment of LT at the Marxists.org site:

https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labor-today/index.htm

I would add an additional comment to Dan’s fine article. His description of the history of IS in labor has remarkable parallels to CP labor efforts during this time period. Many young CPers entered industry, esp steel, auto, but also some “pink collar” and “white collar” unions. When the big shutdowns came, most of us found the white collar jobs we had been educated for. I went to grad school. Our goal was union democracy, but supporting union leaders who were “progressive” (Harry Bridges,e.g.) and helping to build rank and file caucuses with class struggle orientation. Few were recruited to the CP and most of those drifted away. The split in the CP in 1991 also resulted in many steel workers leaving. Anyway, Dan’s article was like looking in the mirror.

Hello Dan,

today I found your articles and am appreciating your knowledge of the tides of history. Your memories, commentaries on actions and groups in Chicago grabbed my attention. I was an infant there in the late 1960s, where my parents were labour and civil rights activists. They also died there at that time. I have followed in my parent’s footsteps as a lifelong socialist activist in Canada and create community circles for people to heal from colonization violence. For several reasons, today I searched once again online for people who knew that place and time in Chicago. And I found your articles here. I am reaching over to hope for context of what was happening, of the tone of the time, of the beliefs and actions of the people working there for equity and human rights.

Would you be open to some correspondence, to fill in some of the gaps I have?

I ask to understand not only who and where I come from, but also the legacy that I continue to live, as that place and time is part of me, and my parents’ beliefs became the frames for my life. I grew up with almost no information about them. I only pieced together their true story recently, finally finding others who understood how to connect the few dots I had. Suddenly my life as an activist makes complete sense. It may be a lot to ask, and yet, 55 years later, their truth is still alive, the work is far from finished, and you continue to write of solidarity and that place and time.

with many thanks,

sincerely,

Christine Zoe