Against the Current, No. 219, July/August 2022

-

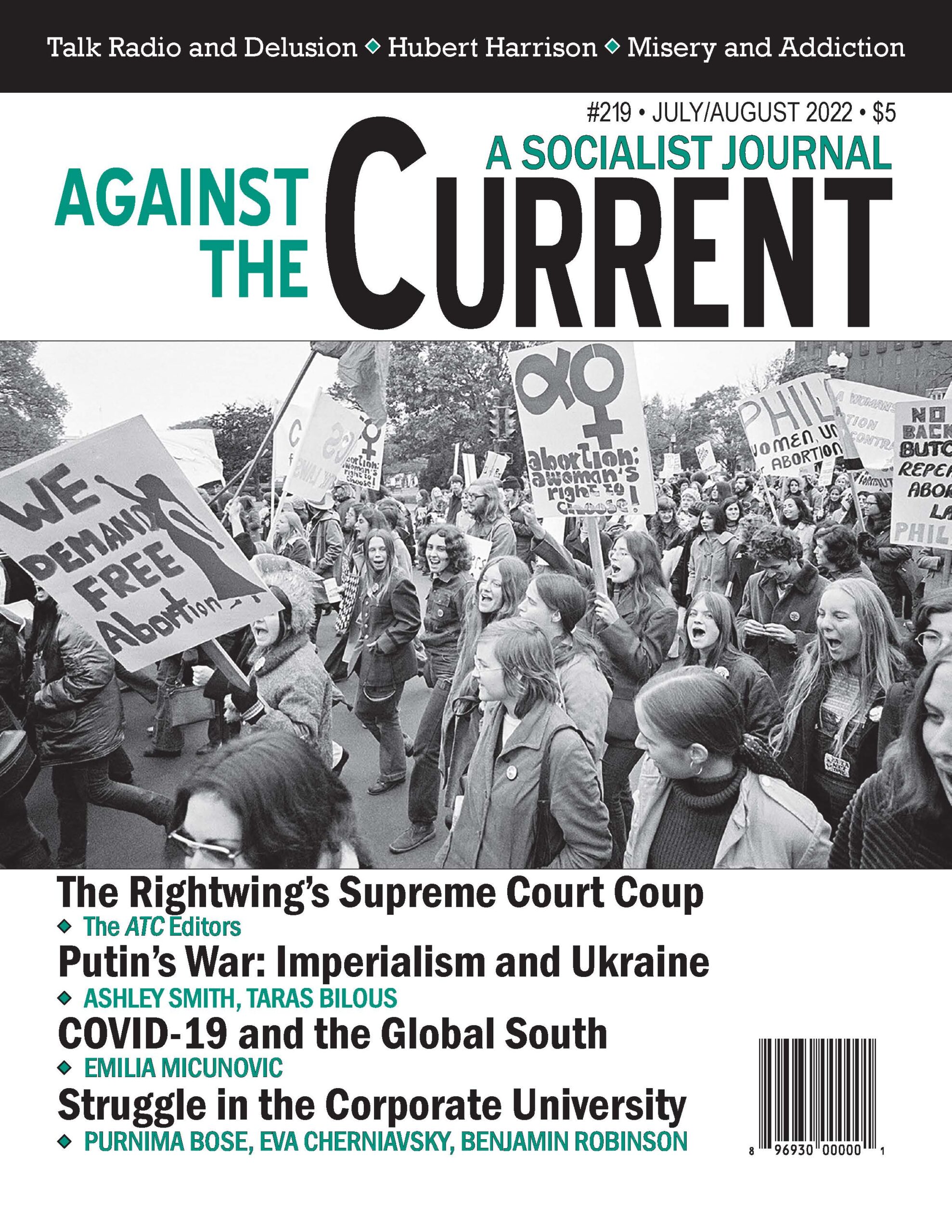

The Rightwing's Supreme Court Coup

— The Editors -

Assange, Donziger and the DNC Media

— Cliff Conner -

A Letter from California's Death Row

— Kevin Cooper -

COVID & the Global South: the Nigerian Case

— Emilia Micunovic -

Ukrainian Leftist Speaks

— an interview with Taras Bilous -

After Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

— Ashley Smith -

The Murder of Shireen Abu-Akleh

— David Finkel - The Case of Derrick Jordan

- Struggle in the University

-

The Competence Curse

— Purnima Bose -

Faculty Governance in Academia

— Eva Cherniavsky -

Renewal of Shared Governance?

— Benjamin Robinson - Revolutionary Experience

-

An Introduction, A Conclusion

— The Editors -

To the Working Class, 1969-1980

— Dan La Botz -

Field Work

— Sam Friedman - Reviews

-

Migration Politics and Criminalization

— Cynthia Wright -

Disability Studies from South to North

— Owólabi Aboyade (William Copeland) -

Mass Misery, Mass Addiction

— Dave Hazzan -

A Giant Rescued from Oblivion

— John Woodford -

Three Mothers Who Shaped a Nation

— Malik Miah -

The High Price of Delusion

— Guy Miller - In Memoriam

-

Oscar Paskal, 1920-2022

— Nancy Brigham

Benjamin Robinson

GRADUATE STUDENT EMPLOYEES at Indiana University Bloomington, organizing with the United Electrical Workers, went on strike for campus recognition between April 13 and May 10, 2022. The strike was then suspended for the summer, with plans for broader and deeper participation when it resumes the fall.

I will share a timeline of key events relating to the Bloomington faculty’s participation in the graduate student efforts. Then I will move on to reflect on what union organizing tells us about how the terms of shared governance have changed since the canonical 1966 AAUP “Statement on the Government of College and Universities” (discussed in Eva Cherniavsky’s contribution to this issue).

No Substitute for Bargaining

In short, I’ll argue from faculty experience with the Bloomington graduate strike and claim that shared governance institutions need to have mechanisms to formulate interests distinct from those of management. These interests should be publicly articulated as a working agenda before joining efforts with university administration.

Cooperation in committee, the standard operating procedure of established shared governance, is not the same thing as bargaining. The inclination to acquiesce to administrative priorities has led to what increasingly appears to be a catastrophic erosion of public priorities and instructional budgets in U.S. higher education. Further, it has led to a redesign by university administration around revenues based on degrees marketed for their return on investment, partnerships targeted for their intellectual property potential and endowment growth. These are key elements of what Purnima Bose calls in her contribution the “corporate university.”

What especially galvanized faculty on the Bloomington campus, beyond the baseline group of members sympathetic to unionization, was the hardline anti-labor response by campus administration, which refused any dialogue with representatives of the union, the Indiana Graduate Workers Coalition-United Electrical Workers (IGWC-UE).(1)

The standoff between the graduate organizers and the administration led to the increasing involvement by faculty over the course of the 2022 spring semester. Largely organized through the campus AAUP chapter and the Progressive Faculty and Staff Caucus listserv,(2) arguments increasingly erupted at regular meetings held by the College dean with chairs and directors; by associate deans with directors of graduate and undergraduate studies; and in the routine meetings of the system-wide Graduate Faculty Council.

Unsurprisingly, the established forum for shared governance, the Bloomington Faculty Council (BFC), was slow to act and assumed no leadership role (on the contrary).

An AAUP-sponsored resolution calling on the provost and administration to begin dialogue with the union passed on a roll-call vote at a special meeting of the BFC the first day of the strike. Yet only one member of the executive committee voted for the resolution (and several were not in attendance). The BFC resolution was mentioned by the secretary (who didn’t support it) in an email to the campus faculty, but otherwise was given little fanfare and received no response from the provost.

Emergency Meeting

That relative indifference by the main established organ of shared governance, however, quickly showed it was out of touch with faculty sentiment. Two weeks into the strike, members of the Graduate Faculty Council and the AAUP convened an emergency faculty town hall meeting. There the faculty spontaneously organized a petition for the BFC Executive Committee to convene, in accordance with the rules of the faculty constitution, a special all-Bloomington faculty meeting. This would be the first such all-faculty meeting since 2005.

The petition, which had four times the required number of signatories, proposed resolutions that would discuss, among other things: voluntary union recognition by the administration; faculty authority over associate instructor appointments; no retaliations against graduate students for participation in the strike; and a potential no-confidence vote in the provost for failure to engage graduate employees.

The faculty council executive committee did convene the meeting for May 10th, the day after campus commencement and the final date for turning in grades. Despite the late date, the meeting, held in the cavernous IU Auditorium, saw a turnout of over 722 faculty members.

Although the executive committee unilaterally removed the no-confidence item from the town hall petition, two resolutions from it appeared on the agenda.

The first reasserted faculty authority over graduate instructor appointments and emphasized existing due-process protections, even calling for an immediate end to the provost’s retaliatory non-reappointments.

The second called on the Board of Trustees and provost to set up the framework for voluntary union recognition and to begin immediate negotiations.

At the meeting, the administration-friendly items were either withdrawn or voted down; the two resolutions supporting the graduate employees passed 683-39 and 623-75 respectively.

Although there was a quorum for conducting business, despite the unprecedented numbers, there was not a quorum for ratifying resolutions. As a result, the resolutions were sent to all faculty for an electronic vote the following week.

Despite the administration’s efforts to sway the vote, the results confirmed the clear will of the faculty to see the graduate student union recognized. The first resolution passed 1605 yes to 308 no (83.8% yes) and the second 1404 yes to 508 no (73.4% yes).

Inside the Discussions

While the timeline gives a blow-by-blow account of key events, it does not give insight into the discussions that so decisively shaped faculty opinion. Of those, I want to focus on the most telling one.

Many faculty with a pragmatic interest in the success of their departments’ academic mission were persuaded by reasoning that asked, “Do we want our graduate workers and our administration to bargain as partners over wages, hours, and working conditions, or do we want adversarial bargaining through strikes and protests?”(3)

Faculty who would not otherwise be concerned with unionization — a common anti-union refrain among faculty council members held that “graduate students are not Amazon workers” — nonetheless recognized that a significant number of our peer and aspirational institutions with unionized graduate students ranked higher than our university did in terms of the Carnegie metrics for research activity.

It thus seemed unlikely to them, despite the warnings from the provost that the culture of shared governance would be eroded by the presence of an industrial union from outside the campus, that the sky would in fact fall if the union were recognized.

It is good such faculty were persuaded by pragmatic arguments that unions are a way to keep up with the R1-Jones while achieving domestic peace among campus stakeholders. But the effort to find common ground (what the 1967 Statement on Government calls a “community of interest”(4)) among distinct campus parties — the graduate students who called the question of collective bargaining, the governing board and administration alarmed by the union threat to their prerogatives, and a faculty largely unaware of the details campus labor conditions but deeply concerned with their core academic missions — should not imply that unionization is simply about finding a new way to integrate graduate students into the administrative process and reestablish the quiescence to which earlier forms of shared governance have fallen prey.

As both Bose and Cherniavsky point out, the modern university is increasingly corporatist rather than collegial in organization.

While the race, class, and gender homogeneity of older forms of campus collegiality have been weakened, so has the idea of normative governance based on the action of informal leadership collegia, such as deaneries and faculty committees. Not only has the civic ideal of the university being run “for the common good”(5) increasingly succumbed to the disillusioned pragmatics of securing returns on investments, but the management structures — by which the governing board of a university and its executives are responsible for delivering nimble decisions regarding endowment foundations, real estate, medical businesses, corporate and federal grant administration, and translational research — are becoming ever more professionalized and hierarchical, a matter of strategic plans, policies, and statutes rather than collective priorities.(6)

This past year members of the IU presidential search committee were for the first time all required to sign non-disclosure agreements, a tool common in the high-stakes worlds of intellectual property management and corporate secrecy, but only recently in collegial searches. And perhaps unsurprisingly, the presidential search wound up being just such a shadowy affair, marked by the trustees bypassing their own gagged search committee to secure an appointment better in accord with their unstated goals.(7)

In short, old models of shared collegial governance have become unsuitable for today’s universities. While universities haven’t entirely abandoned the democratic ideals imagined for them in John Dewey’s turn-of-the-century Progressive Era, they fall under a heavier obligation to serve as centers of corporate revenue generation in the contemporary knowledge economy.(8)

The Lesson of Unionization for Shared Governance

The lesson of unionization is thus not that unions are a new way to achieve campus business as usual by locking instructional assistants into contracts with no-strike clauses and a strictly circumscribed list of items eligible for negotiation. On the contrary, what underlies the exciting revival of shared governance that the unionization efforts on the Bloomington campus have fostered is the importance of the associational over the structural dimension of unionization.

The unified campus response against the administration’s harsh anti-labor line has demonstrated that graduate employees are not seeking a transactional outcome, but a participatory process of interest formation and public representation.

They have chosen to affiliate with the United Electrical Workers, a union known for its rank-and-file democratic locals and emancipatory political and community orientation.(9) As the UE itself formulates their distinction in the labor movement, the “UE’s founders were determined to avoid the bureaucratic, top-down control that was characteristic of the existing craft unions.”(10)

Faculty shared governance needs to focus on precisely this dimension. It is significant that the governing councils of the AAUP and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) decided this past March 2022 to pursue affiliation, cementing a focus on campus labor that took clear shape in 2012 with the election of Rudy Fichtenbaum and his Organizing for Change slate to the leadership of the AAUP.(11)

It is not a final collective bargaining agreement that is central in this evolution of shared governance, but the principle that key stakeholders meet together to develop their values and positions before they come to the bargaining table.

In this way, shared governance can begin to move universities away from the mentality of zero-sum budgeting, which seeks to grow revenues for institutional priorities distant from the classroom, library or laboratory, while maintaining that every increase in a graduate stipend or staff salary has to be financed with a cut in faculty pay or the number of tenure track positions.

If faculty re-establish the institutions to deliberate not only within the corporatist framework of strategic plans and blue-ribbon committees, but also together with those stakeholders who share an interest in reinvesting in instructional budgets, expanding access to knowledge, building an equitable civil society, and reinvigorating the ideals of the university in the service of the public good, then they can play a substantial role in redirecting higher education toward the real social and not merely technical challenges of our times.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that no member of the Bloomington Faculty Council Executive Committee voted for the AAUP resolution. It has been corrected to reflect that one member voted in favor. –ed.

Notes

- Website of the Indiana Graduate Workers Coalition-United Electrical Workers: https://www.indianagradworkers.org

back to text - AAUP Graduate Employee Strike FAQs: https://www.indianagradworkers.org

back to text - Rationale for the “Resolution of the Bloomington Faculty Concerning SAAs and the Administration,” Special Meeting of the Bloomington Faculty, Monday May 9, 2022: https://institutionalmemory.iu.edu/aim/bitstream/handle/10333/14495/Rationale%20for%20Resolution%20on%20IGWC-UE%20recognition%20%28electronic%20ballot%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

back to text - American Association of University Professors (AAUP), the American Council on Education (ACE), and the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges (AGB), “Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities” (1966): https://www.aaup.org/report/statement-government-colleges-and-universities

back to text - AAUP, “Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure” (1940): https://www.aaup.org/report/1940-statement-principles-academic-freedom-and-tenure

back to text - Davarian L. Baldwin, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities (New York: Bold Type Books, 2021).

back to text - Emma Pettit, “This Professor Investigated a Presidential Search at His University. It Said He Was Out of Line,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Nov. 12, 2021.

back to text - Joan Scott, “Knowledge for the Common Good: A plenary presentation from the AAUP’s 2019 annual conference,” Academe (Fall 2019): https://www.aaup.org/article/knowledge-common-good#.Yom3XC-cZQI

back to text - James Young, Union Power: The United Electrical Workers in Erie, Pennsylvania (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2017).

back to text - UE, “Them and Us Unionism” (July 2020): https://www.ueunion.org/ThemAndUs/UE_Them_and_Us_Unionism.pdf

back to text - Kaustuv Basu, “A Change in Philosophy?” Inside Higher Ed, April 20, 2012: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/04/20/aaup-about-change-course

back to text

July-August 2022, ATC 219