Against the Current, No. 218, May/June 2022

-

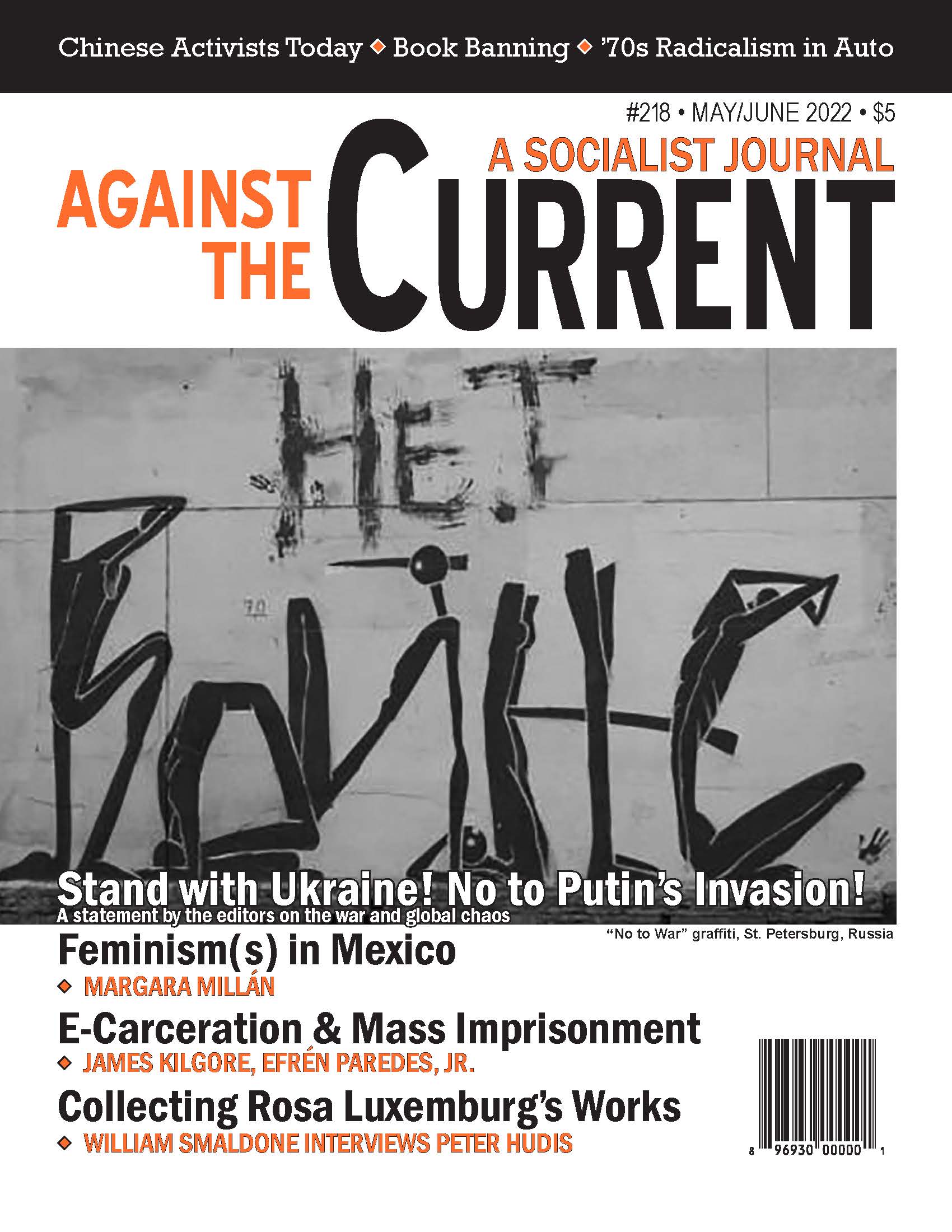

Out of the Imperial Order: Chaos

— The Editors -

"Nationtime": The Black Political Convention

— Malik Miah -

Rising Up at Amazon

— Dianne Feeley -

Book Banning Past and Present

— Harvey J. Graff -

Punishing the Criminalized Sector of the Working Class

— James Kilgore -

The Invisible Chinese Activists

— Mo Chen -

Feminism(s) in Mexico

— Margara Millán -

Faiz Ahmed Faiz: The Restless Traveler

— Ali Shehzad Zaidi -

The Complete Rosa Luxemburg

— William Smaldone interviews Peter Hudis - Revolutionary Experiences

-

Introduction to Revolutionary Experience

— The Editors -

On-the-line in Auto -- 1970s-1990

— Elly Leary -

Organizing in '70s Wisconsin

— an interview with Jon Melrod - Reviews

-

Prison Abolition: A Primer

— Efrén Paredes, Jr. -

How Alice Became an Activist

— Adam Schragin -

When Radicals Ran the U.S. Congress

— Mark Lause -

Dust Bowl Chronicler

— Cassandra Galentine -

Surveying Revolutionary Thought

— Herman Pieterson

Malik Miah

FIFTY YEARS AGO, the steel mill city of Gary, Indiana hosted an unprecedented event: over 8,000 Black people gathered in a three-day National Black Political Convention, March 10-12, 1972.

The meeting discussed a Black Agenda that raised the proposal of political independence from the two major parties and whether an independent Black political party could be forged.

This writer participated in the convention, one of dozens of young socialists who had been involved in the civil rights and anti-police violence struggles, as well as the antiwar movement that had broad support among African Americans.

I had organized protests in my home city of Detroit in high school and college. I came to Gary as both a revolutionary socialist and militant Black nationalist. My organizations — the Young Socialist Alliance and Socialist Workers Party — expected “the coming American socialist revolution” to be a combined struggle of the working class for power and for national liberation of the oppressed Black nationality.

Power of the Moment

Despite political and ideological differences, participants were united in frustration with the Democratic and Republican parties whose national conventions loomed on the horizon. We wrestled with one major question: Should Black people build within, or from outside, the system?

As part of the Black Agenda, the Gary Declaration issued by the convention stated that the political system was failing Black people and the only way to address this problem was a transition to independent Black politics.

The concept of self-determination for an oppressed nation within an imperialist state like the United States means first, organizing independently of the mainstream political structures and posing openly: Should we demand our own nation?

“A schism had developed among those who wanted to work within the system versus Black nationalists who were basically saying it needed to be torn down,” said Leonard Moore, a history professor at the University of Texas-Austin and author of a book about the event.

“But there was a collective feeling that ‘We need to come together, because we’re all over the place.’ Organizers wanted to get all these Black voices around the table.” (Quoted in USA Today, February 1, 2022)

The context was important. There were few Black elected officials anywhere and there was a powerful anti-Vietnam war movement that most civil rights and Black nationalists supported.

Martin Luther King, Jr. had spoken out in 1967, one year before his assassination. His voice then was a minority among the Black liberal establishment. That changed afterwards.

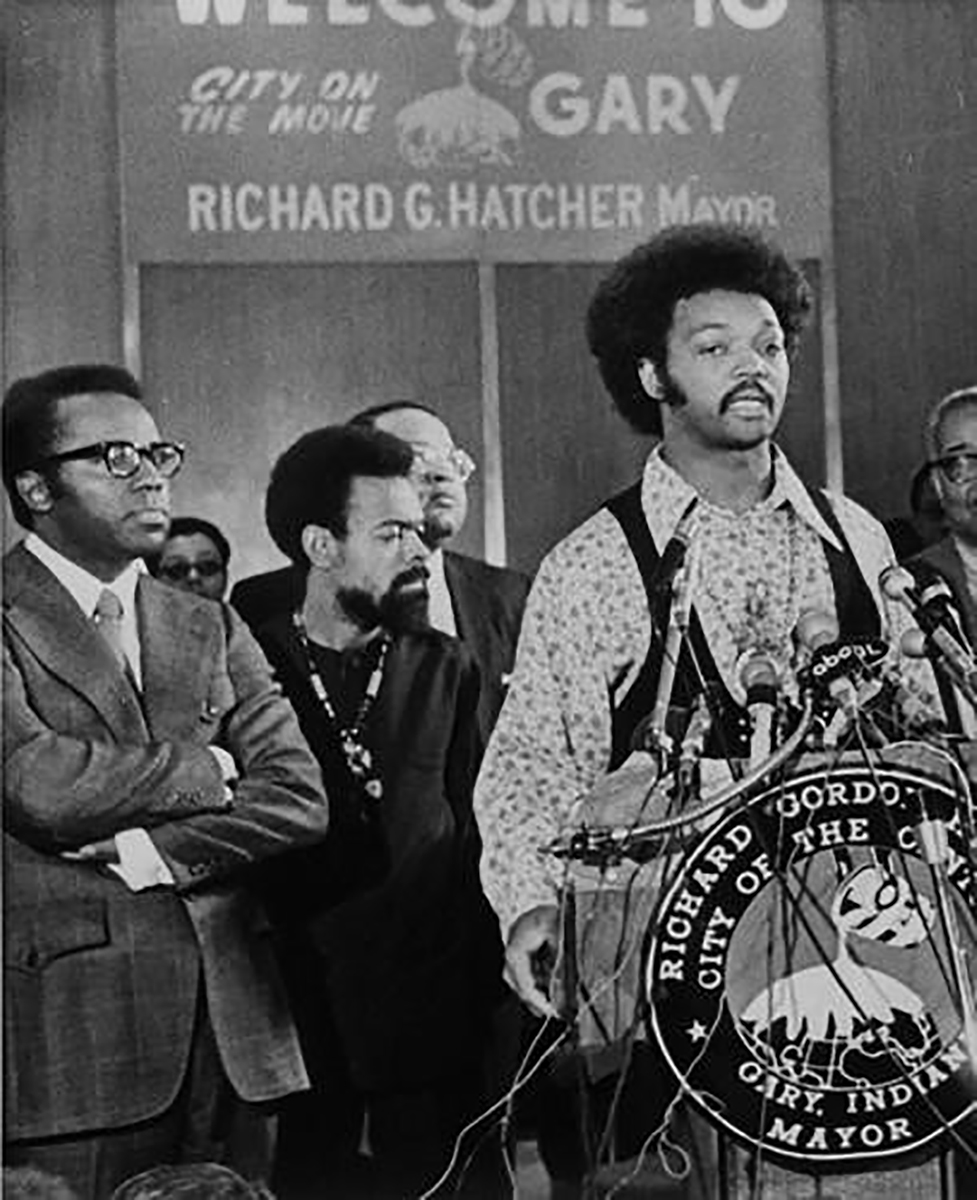

The historic gathering was arranged by Gary Mayor Richard Gordon Hatcher, one of the first Black mayors at the time, poet and prominent Pan Africanist Amiri Baraka, and Democratic U.S. Rep. Charles Diggs of Detroit, Michigan, chair of the newly formed Congressional Black Caucus.

There were young activists and entertainers like Harry Belafonte and Dick Gregory, socialists, and Pan-Africanists.

Rev. Jesse Jackson of Operation PUSH stirred up the crowd with a forceful call-and-response speech declaring it was: “Nationtime.”

“I don’t want to be the gray shadow of a white elephant or the gray shadow of a white donkey,” Jackson told the audience. “I am a Black man, and I want a Black party.”

He asked: “For Black Democrats, Black Republicans, Black Panthers, Black Muslims, Black independents, Black business owners, Black professionals, Black mothers on welfare – what time is it?”

“Nationtime!” the crowd cried.

(A documentary unearthed in a Pittsburgh warehouse in 2018, narrated by Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte, “Nationtime” presents a dynamic and powerful look at the three-day Gary convention. See the film trailer.)

Why the Convention Happened

The national Black community was still shaken by the King assassination four years earlier, and by police brutality and worsening conditions in the urban “ghettos.”

In 1972, crisis plagued Black America. Heroin ravaged inner cities, Black soldiers were dying in Vietnam and unrest from Chicago, Newark, and Detroit to Los Angeles had instilled a realization that legal civil rights were inadequate without addressing Black poverty and unemployment.

With the Black Power movement at an elevated level, and the formation of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971, two growing camps — nationalists and integrationists — found themselves at odds.

“Black people were increasingly the margin of difference for Democratic candidates,” said Ron Daniels, a member of Ohio’s convention delegation and now president of the Institute of the Black World 21st Century, a Black empowerment organization. “But the feeling was they were not getting rewards proportionate to their support.”

Hatcher, who represented the establishment but also identified with Baraka’s nationalist views, approached leaders of potential sites such as New York, Chicago and Atlanta, but found them hesitant to host such an event, fearing chaos and violence.

Instead, he offered up Gary — specifically West Side High, since the city of 175,000 had no hotel large enough to accommodate such a large gathering.

The so-called Steel City, 40 miles east of Chicago, seemed an unlikely place for a political insurgency. But Hatcher was one of the country’s first elected Black mayors, and with a Black police chief, the city represented what Black people could do at a local level.

Hatcher had Gary’s City Hall draped in red, black, and green banners.

“Mayor Hatcher was a visionary,” said Vernon Smith, an Indiana state representative of 32 years who attended the event as a newly elected Gary city council member. “He saw the strength that could be amassed if we brought everyone together.”

Historic Importance

The three-day event would ultimately form a National Black Political Assembly to implement its 68-page agenda. But it would be eight years later that a National Black Independent Political Party (NBIPP) was created.

The euphoria of wide unity evident at the gathering would be short-lived. The most radical pro-Black party wing lost, and the establishment figures became elected officials, businesspeople and academics.

Socialists saw the gathering as historic in the moment no matter what later happened, showing that militant Black nationalism is a byproduct of systemic racism and capitalism.

Our belief is that the nationally oppressed can win self-determination only with the overthrow of the capitalist system. The fight for democratic freedom and equality is the road to do so.

My views were reflected in an article by Derrick Morrison, in The Militant (April 14, 1972):

“Despite a muted discussion and bureaucratic organization, the National Black Political Convention held March 10-12 in Gary, Ind. reflected a new stage in the developing nationalist consciousness of Black people. Up to now, the most vigorous examples of the organization of Black people as an oppressed nationality had been provided by Black students, Black GIs, Black prisoners, in some cases Black workers, and in a few cases Black women.

“But now even the Black Democratic politicians are reflecting the deepening discontent and nationalist sentiments of the Black community. Only a few years ago they denounced as racism in reverse all efforts at organizing Black people as a people; now they are legitimizing this concept on new levels.”

The Movement for Black Lives in 2020 cited the historic gathering as a model for its 2020 virtual convention, and this April 2022, Mayor Ras Baraka of Newark, New Jersey, is continuing his late father’s legacy by convening a 50th anniversary event in Newark along with Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba of Jackson, Mississippi.

This year’s gathering, Baraka said, marks a chance for the community to harness the resolve and pledges made in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter movement to forge an agenda around which to politically organize — the same goal sought in 1972.

“It’s more than just a festive occasion,” Lumumba added. “We are coming in with a real desire to push forward Black America’s agenda. We may have more Black leadership nationwide, but we still have rampant poverty, failing infrastructure in our communities and issues of equity and justice. All of those need to be addressed with our collective genius.”

A Period of Upheavals

The year 1972 was a period of rising class struggle and resistance to racism, national oppression, sexism and other issues.

The Black Liberation movement had led the way since the 1960s and inspired other social groups. In the Southwest, Mexican American and Chicano communities raised similar democratic demands for La Raza.

Puerto Ricans in New York City, Chicago and other urban areas demanded self-determination for Puerto Rico. Militant activists organized the Young Lords (inspired by the Black Panther Party) in Chicago and the Bronx, New York in fighting for community control.

The year was also a key period for the women’s rights movement. The central issue during this second wave of feminism was abortion rights, the fight to control their own bodies. The Supreme Court had not yet ruled in favor of that basic human right, which today’s Court plans to overturn.

The Gay and Lesbian rights movement was also on the rise across the country, not just in San Francisco and New York City.

The first Earth Day occurred in 1970 and the Environmental movement pressured the Nixon administration to set up the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) in 1970.

Labor unions were fighting back, especially Black workers who were placed in the worse jobs and historically excluded from the skilled trades such as mechanics and pilots.

In basic industries including coal and iron ore mining, steel production and auto manufacturing, union workers were winning stakes and internal democratic reforms. Miners for Democracy threw out the Tony Boyle gangster union bureaucracy. Steelworkers Fight Back was challenging the entrenched leadership.

In the auto workers union, reform and radical groups like the League of Revolutionary Black Workers was an important force for militant activism. Public sector union militancy was also emerging among teachers and heath care workers.

The biggest social movement in 1972 was the antiwar movement against the U.S. war on the Vietnamese people. The final U.S. defeat was still three years away.

African liberation struggles were advancing. As an activist in the Pan Africanist movement, I joined in protests in support of the armed national liberation movements in the Portuguese colonies of Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Islands.

The fall of Portugal’s authoritarian dictatorship did not occur until April, 1974 when left wing officers took power. The Portuguese African colonies soon won their independence.

White rulers in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and South Africa were still in power. Nelson Mandela was still in prison and apartheid did not fall until 1994.

The events of 1972 thus were part of other major social political changes that rocked the United States and world. Some led to freedom as in the African colonies; others led to the deep incorporation of the Black political leadership into the Democratic Party and capitalist institutions.

Many young people went Left and became more committed to revolutionary change. Gary reflected all these elements — liberalism and revolutionary nationalism — at a moment when it was unclear what the future would become.

Seeking Political Leverage

Long before the Gary convention, political gatherings of Black people had taken place periodically since the 1820s in cities such as Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Chicago and New Orleans.

Organizers of the 1972 event at minimum aimed to inspire more Black people to pursue political office.

Black Congresspeople hoped to leverage the resulting agenda to extract concessions from both parties at the upcoming conventions. At the time there were fewer than 1000 Black elected officeholders across the country, from local and state to federal levels. Today there are thousands (including Black Republicans).

The event also involved Coretta Scott King and Betty Shabazz, the widows of King and Malcolm X, as well as James Brown, Isaac Hayes, Muhammad Ali and Richard Roundtree, star of the 1971 film “Shaft.”

Delegates gathered around signs designating their home states, taking notes on the proceedings.

The gathering was not without rancor. Shirley Chisholm of New York, the first Black person to seek a major party’s presidential nomination and the first woman to seek the Democratic Party nomination, boycotted the convention when organizers failed to endorse her, a rejection she saw as sexist. Instead Chisholm traveled to Florida to stump for votes.

NAACP leaders objected to what they felt was the “separatist” nature of calls for a third party reflected in the Gary Declaration, which read: “By now we must know that the American political system, like all other white institutions in America, was designed to operate for the benefit of the white race: It was never meant to do anything else.”

The document called for radical change. “Such responsibility is ours,” it said, “because it is our people who are most deeply hurt and ravaged by the present systems of society.”

Mayor Hatcher advocated giving Democrats one last chance, but declared in his keynote address that if the parties failed the community again, they would suffer the consequences. That included the threat of a third party that he claimed would siphon away support from other communities of color, as well as “the best of white America.”

“We shall take with us many a white youth nauseated by the corrupt values rotting the innards of this society,” Hatcher said.

“Nationtime,” Unity and Decline

Bobby Seale, who along with Huey Newton founded the Black Panthers in 1966, was among those at the convention emphasizing political involvement, frustrated by what he saw as time wasted debating cultural nationalism.

“It’s not about that,” he said he recalled thinking. “It’s about political power. They’re the ones who manage the money.”

Then came Jesse Jackson’s rousing “Nationtime” oration.

“You could hear it reverberating Marcus Garvey,” recalled former NAACP executive director Ben Chavis, then a North Carolina delegate, in a 1989 interview conducted for PBS: “Eyes on the Prize II.”

“You could hear it reverberating all those prize struggles from the ’20s, and the ’30s, and the ’50s and the ’60s. I mean, it came to be fulfilled in that moment, of crying that it’s Nationtime, now — not next year, not next century, but now. In 1972. In Gary, Indiana.”

Within months of the convention, however, the cohesion had begun to dissipate as mainstream Black leaders withdrew support for the Agenda, citing contentious issues like reparations and its support for Palestinian liberation.

The final Agenda was considered overly broad, alienating many while trying to please all. “They willy-nilly adopted everything,” one delegate said. “This led to conflicts that would lead to dissolution of the whole thing. There was no way those fundamental differences could come to any compromise.”

In 1974, a second Black convention would follow in Little Rock, Arkansas, with other gatherings taking place only sporadically afterward.

The National Black Political Assembly, which had been formed as a compromise to those calling for a third party, eventually fizzled, victim of an ill-defined infrastructure.

For convention organizers, simply pulling off the gathering was itself a victory, and it succeeded where they intended — at the ballot box.

“If you’re looking for 100% unison, it was doomed going in,” an organizer said. “The true value of the convention wasn’t necessarily the agenda or the position papers. It was that immediately after the convention Black people went home and ran for office. It ushered in a new Black political culture. By the end of the ’70s, you had several thousand Black elected officials.”

In 1973, Atlanta and Los Angeles elected Black mayors in Maynard Jackson and Tom Bradley. “Black folks came off the sidelines and decided that Black politics mattered,” Daniels said.

With the focus on elected officials, the Black Power movement began to decline. Meanwhile, the Congressional Black Caucus took on the community’s umbrella leadership role.

The convention laid the groundwork not just for Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign — but likely Barack Obama’s presidential campaign and victory as well as Kamala Harris’s vice-presidential run.

Political Incorporation

Of course, more Black faces as part of the ruling parties and state structures did not benefit everyone. In the wake of successive recessions, deindustrialization, the 2008 financial crash and Covid, the majority of working class African Americans are less well off than in the 1970s.

Some 12 years later in 1984 and again in 1988, Jesse Jackson ran for the Democratic Party presidential nomination. Under a radical democratic platform echoing the Black Assembly, his 1988 Rainbow Coalition created an unprecedented multiethnic support network even winning some state primaries. Yet we were no closer to “Nationtime” or a Black independent party.

The fundamental political error made at those conventions, beginning with Gary, was the pursuit of a strategy of working in or with the Democratic Party and looking towards its politicians for leadership.

Instead of an independent course, the result was incorporation into the system.

The NBIPP Effort

Eight years after Gary, it became clear that the strategy of working within the political system was a failure. The Black party should have been formed out of the 1972 convention, even if only by the most left wing sectors of the Black movement.

The National Black Independent Political Party came too late in 1980. Jackson did not join it as he had become a player in the Democratic Party.

Yet it was significant that the NBIPP was formed. It represented the radical nationalist perspectives of the Black rights movement. That voice remains alive to this day.

D.L. Chandler wrote recently:

“The National Black Independent Political Party (NBIPP) was formed in November 1980 as a response to the growing concerns of the African American community and their place in the political ecosystem. To date, the NBIPP remains as perhaps the most prominent example of Blacks breaking with the major two-party system of Democrats and Republicans.

“Keeping true to its overall mission, the national charter expressed its concerns and aims in pointed fashion.

“‘The National Black Independent Political Party aims to attain power to radically transform the present socio-economic order. That is, to achieve self-determination and social and political freedom for the masses of Black people. Therefore, our party will actively oppose racism, imperialism, sexual oppression, and capitalist exploitation,’ the charter stated.

“The NBIPP disbanded after just six years with little in the way of explanation. Although several books have since been written about the rise and fall of the NBIPP, few outside documents point to the machinations behind the party’s end.”

As a supporter and promoter of NBIPP, I knew it was nearly impossible for it to run candidates. The Old Guard, including Jesse Jackson and the Black elected officials had decided that independent politics was not the way forward for their careers and the Black community.

The Black middle class grew in the post-civil rights revolution era. It became the base for these new empowered Democrats.

Nevertheless, the Black Agenda created in 1972 and the formation of NBIPP marked milestones for the Black left, including those of us active in the socialist movement.

It was my view that an independent Black party could lead to increased street actions and multiethnic unity, including the formation of an independent Labor party unifying Blacks, and the broader working-class population.

We thought that radical change was possible soon. NBIPP’s collapse, in fact, was due to objective changes in the class struggle in the 1980s.

Backlash and White Supremacy

The right-wing white backlash was beginning everywhere. Some eight years after Gary, Ronald Reagan was elected president. He openly appealed to white racism.

One of his first actions was attacking Black rights (then falsely calling affirmative action programs as a form of “reverse racism”) and the union movement. He and many Democrats also criticized busing programs to desegregate public schools.

Reagan broke the strike of air traffic controllers in 1981, and the AFL-CIO did nothing. This gave employers the green light to use scabs and go after private and public sector unions.

A flaw in our socialist analysis of the Gary event was that we never explicitly explained the ideology of white supremacy.

Socialists and militant nationalists attacked the root cause of national oppression and racism — the capitalist system. But the ideology of white supremacy was key to capital’s divide-and-rule methods.

Whites are taught at an early age that people of color, especially Native Americans and descendants of slaves, were inferior. Racism is central to capitalist rule.

Key to Building Unity

Unity did happen in the 1960s at the height of the civil rights battle. But it was never as strong as needed.

Many on the left saw class “bread and butter” issues as the way to bring white and Black people together. But downplaying the national oppression of Blacks and others is why the ruling class has effectively divided the working class since even before the 1776 revolution.

White people including workers will and can be radicalized around issues of racism, as the anti-police violence movement in 2020 showed. But it must be done openly. Unconscious bias must be confronted.

The far right understands this better than liberals. They use “cultural” issues to convince many white people to protect their advantages as whites. It is not a surprise that these same elements want to ban books from schools that discuss Black history and racism.

Despite their unfulfilled promise, the Gary convention — its debates and written program — and the later formation of NBIPP remain important events to study and learn from.

May-June 2022, ATC 218