Against the Current, No. 217, March/April 2022

-

Roe v. Wade: Blood in the Water

— The Editors -

Teamster Election: New Openings, Real Challenges

— Barry Eidlin -

Billions for Philippine Military & Police

— John Witeck -

bell hooks -- Fiery Black Feminist

— Malik Miah -

In the Classroom: Reparations Won

— an interview with William Weaver & Lauren Bianchi -

The British Labour Party's Quest for the Past

— Kim Moody - Free Leonard Peltier Now!

- Stop Thief!

- International Women's Day

-

Poland: Women's Mass Protests

— Justyna Zając -

Intersectional Feminism

— Alice Ragland -

Lives of Enslaved Women

— Giselle Gerolami -

Challenging the Comfortable

— M. Colleen McDaniel - The '60s Left Turns to Industry

-

Introduction

— The Editors -

The Movement, the Plants, the Party

— Dianne Feeley -

Miners Right to Strike Committee

— Mike Ely - Reviews

-

Times of Rebellion

— Micol Seigel -

New Light on the Young Stalin

— Tom Twiss -

A Russian Civil War Chronicle

— Kit Adam Weiner -

Art Overoming Divisions

— Matthew Beeber - In Memoriam

-

Mike Parker (1940-2022)

— Dianne Feeley

Mike Ely

I HAVE TWO stories to tell.

The first is about a massive wave of militant working class struggle.

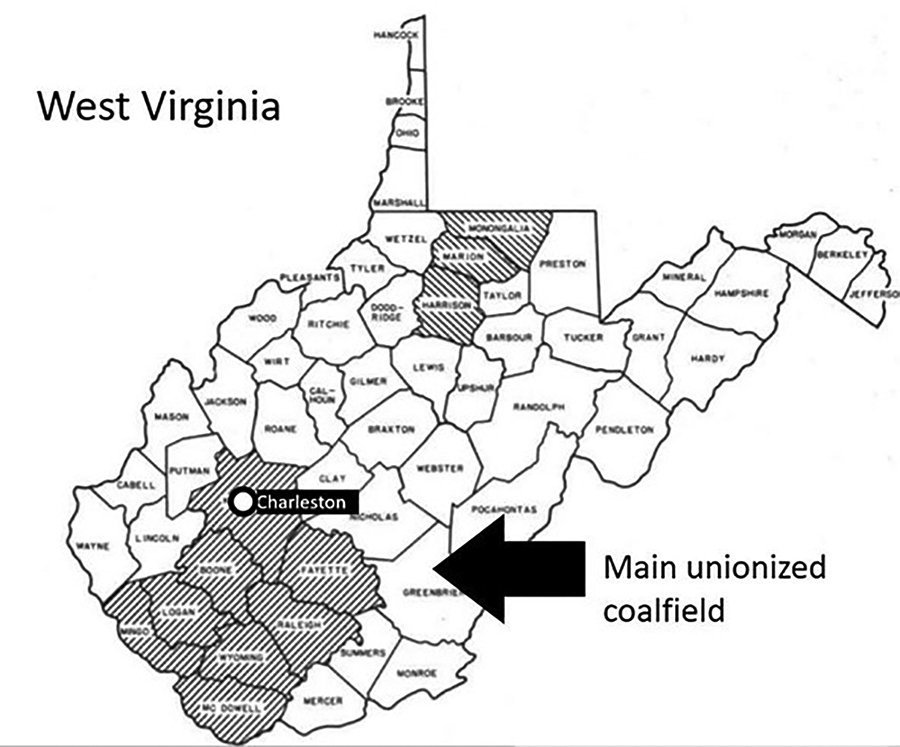

For 10 years, between 1969 and 1979, coalminers in the United States waged relentless class struggle centered in southern West Virginia. Their weapon was the wildcat strike — thousands of illegal walkouts broke out at hundreds of scattered worksites. They built into explosive nation-wide strikes spread by picket movements.

The movement’s opening shot was the 23-day Black Lung strike in 1969 when 40,000 miners walked out and forced West Virginia’s legislature to recognize and compensate Black Lung disease.

Something new and determined had broken free in the coalfields. After World War II, hundreds of thousands were driven into unemployment by mechanization. They lived through a bitter powerlessness — imposed by the industry’s slump and exploited by their union’s corrupt gangsters.

For 20 years, almost no new miners were hired. Then by the mid-1960s, an aging generation needed to be replaced. The new workforce, many of them Vietnam vets, bristled with a rebellious fuck-you attitude. They simply weren’t willing to live as their parents had.

Young militants met outrages by mine operators with countless walkouts across southern West Virginia. The corporations responded with a flood of federal court injunctions. Judges ordered miners back to work and threatened heavy fines and jailing for continued defiance.

The networks of militants refused to give up their wildcat weapon. They defied injunctions — and increasingly spread their actions to new mines. By the mid-’70s, local strikes over grievances turned into a much larger fight against all injunctions, fines and jailings.

Miners rallied to a new demand: Their right to strike had to be recognized — by contract, the legal system, and their own union leadership.

In the summers of 1975 and 1976, miners waged two countrywide strikes against federal injunctions and jailings. The walkouts pulled out 80,000 to 100,000 miners — behind this demand for the right to strike. These “right to strike” strikes were marked by shootings, jailings, de facto martial law in some areas, attempts to organize scabbing, and intense anticommunist hysteria in the press.

The upsurge culminated in a bitter 111-day contract strike during 1977-78. Miners defied everything thrown at them — including President Carter’s Taft-Hartley injunction.

This decade-long miners’ upsurge was raw, illegal, violent, and seemingly irrepressible. It was marked by amazing solidarity and heroic sacrifice. It forms the largest, most sustained wave of working class militancy in modern U.S. experience. Yet it remains virtually invisible within both scholarly labor history and leftist memory.

My second story is about communist cadre within that upsurge:

The Revolutionary Union was a communist organization, born around the Bay Area, that grew explosively across the country by 1970. The RU rejected the gray, conservative model of the Soviet Union. We drew our inspiration from the stormy struggles of China’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The RU rejected “lesser evil” electoralism and organized militant support for the Black Panther Party.

The core idea animating the RU was to create conditions for a socialist revolution in the United States — including a new vanguard communist party, a hard-core revolutionary workers’ movement, and broad alliances with many different progressive strata and struggles.

We joined to take revolutionary politics deep into the working class. Once RU went national, it redistributed its young communist cadre — shifting them from campuses and counterculture centers. We sent teams of organizers deep into industries where the ’60s movements had rarely reached.

By late 1972, six RU cadre arrived in southern-most counties of West Virginia. Two years later, a second cohort took up work in the mountains further north, just below Charleston. Our Maoist crew came to play an influential, sometimes leading, role among the miners.

We helped give the movement structure, common demands and an uncompromisingly radical thrust. Meanwhile, our cadre injected their internationalism, anti-racism and dreams of socialist revolution far and wide within the whirlwind.

I’m writing a book-length treatment of this experience. Let me share a short sketch here.

Dreams of a Revolutionary Workers’ Movement

By 1970, U.S. polls estimated that over three million people consciously wanted a revolution. Over a million students considered themselves “revolutionaries.”

We had a serious movement but not nearly enough to seriously go for power.

Repression was hitting the Black Liberation movement hard. Many of us became convinced that the revolution urgently needed to be spread into new corners of society. In particular, we were determined to seek out radical elements within the multi-racial working class and help them become the leading component for our future revolution.

About 10,000 young radicals of diverse trends resolved to go into the working class.

My partner Gina and I were 20 when we headed for West Virginia. We had organized for militant antiwar and Black liberation actions since high school. We left college after the Kent and Jackson State shootings — and helped organize white working-class youth around Panther-style politics.

Gina worked in the Post Office, then in a Midwestern lens factory. I had a job first in a sweatshop shoe factory, then in a steel forge. After joining the RU, we worked closely with the Black Panther Party for a year — producing a joint community newspaper and studying communist theory.

Other comrades arriving in West Virginia had their own distinct experiences. Some had been radicalized in the Peace Corps. Others had experienced Appalachia as part of the VISTA program.

One comrade had been tried for sedition in Kentucky. Another had been a grunt during Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia who then joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). With the RU, he helped organize a radical caucus and walkout in Post Office terminals.

In short, our RU cadre had early experiences with working class struggle plus some initial training as communists.

As we arrived, we obviously knew big things had kicked off in the coalfields. The black lung strike won its demands three years earlier. The rank-and-file upsurge left the UMWA’s Boyle regime weak and exposed.

When the Labor Department imposed a government-supervised election, a hastily assembled reform coalition, Miners for Democracy (MFD), won a lopsided victory. Arnold Miller, a retired rank-and-file miner, became the new union president.

What we couldn’t know was that we were entering a tornado of struggle that would escalate, year by year, for a decade.

Our RU coalfield project defined its goals using a passage from Lenin:

“The Party’s activity must consist in promoting the workers’ class struggle. The Party’s task is not to concoct some fashionable means of helping the workers, but to join up with the workers’ movement, to bring light into it, to assist the workers in the struggle they themselves have already begun to wage.”

We did not intend to adopt whatever politics were spontaneously dominant among the workers. The key phrase for us was “bring light into it.” By light, we meant revolutionary politics. We said among ourselves, “Bringing Marxism-Leninism to the working class is bringing it home.”

In other words, our project’s ultimate goals weren’t building some “fighting union movement” for reform demands. We were communists seeking to connect a section of working class radicals to the world of anti-racist, internationalist, revolutionary politics. The plan intended to transform both the working class and the existing revolutionary movement.

We dove into the picket cores of the wildcats. We joined the Black Lung Associations. We conducted class-conscious agitation wherever we worked and much more.

Structures of Struggle

The miners’ upsurge was launched by militants elected to the lowest levels of the union structure.

In each county, there were several mines with highly militant leading cores. Local union leaders are all working miners — who take time from work to confront the mine managements over grievances.

The militant mines struck often over injustices. Each night, local news would announce new injunctions ordering a return to work at this mine or that.

Increasingly, such local cores also led wider networks from surrounding mines. They could summon a picket movement to spread and sustain wildcats when they went regional.

In some ways, the once-comatose UMWA had already been reborn a “fighting union” by the late 1960s, at least within the grassroots networks built among the younger workers. Many miners expected the new MFD officials to provide a unifying, central leadership for the next emerging fights.

So it was a shock to many that Arnold Miller and most new officials soon launched their own hostile attacks against wildcat strikes and the militants who led them. Within a couple of years, these new UMWA officials were actively organizing scab movements. They were making secret backroom deals with the Bituminous Coal Operators Association. And they tried to expel communists from the union.

This bitter outcome of this MFD experience is important for today’s radicals to understand: The MFD’s takeover remains the single most successful rank-and-file insurgency ever within a major industrial union. This reform movement elevated genuine rank-and-filers into every level of union office. Rank-and-file conventions democratized the UMWA national and regional constitutions in every conceivable way. (I was a delegate at one.)

Yet in the end, the top union structures again showed up on the battlefield as enemies of miners’ demands and actions — just as Tony Boyle’s gangsters had.

That’s a sobering experience for anyone who expects that overturning corrupt union cliques and democratizing union structures will naturally produce fighting unions and foster conditions for promoting socialism.

The problem is not that Arnold Miller had been a fake militant or that personal flaws caused his betrayal. The truth is that this new union leadership was plopped into the existing post-World War II framework of collective bargaining — where trade unions are required to limit demands to wages and benefits at contract time.

Union officials are legally required to enforce uninterrupted production. To compel their compliance, the apparatus of collective bargaining gives the state power to punish and even destroy union structures that don’t control the workforce.

Federal authorities actively supported reform in the UMWA. They didn’t do this to hand the coal miners’ movement a new “fighting union” leadership. They allowed the black lung activist Miller to replace the exposed murderer Boyle so that a new officialdom would have enough legitimacy to rein in the miners.

Ironically, the most positive feature of the reform UMWA leadership proved to be its profound weakness. The union hierarchy remained split into hostile cliques. There was no coherent top-down structure capable of enforcing discipline on the workers.

The year 1974 saw several significant strikes. The statewide Great Gas Protest by 20-30,000 miners was the first strike we participated in. After a major shooting, the governor caved in and dropped his hated gas rationing rule.

Battered by escalating strikes, the BCOA doubled down. More court injunctions showered down on locals. Fines and jailings were increasingly carried out. In the middle of this, the Miners Right to Strike Committee (MRTSC) was born.

The MRTSC and Communists

By 1974, the ad hoc structure of the early wildcat movement was running up against its own limitations. Loose networks had previously sent out pickets whenever larger strikes were needed. The picketing relied heavily on miners’ famous solidarity with anyone who showed up asking for help.

But now, the authorities were actively targeting the most militant local crews with heavy reprisals. This produced a churn among the militants. Some respected leaders stepped back when threatened with prison. Some considered careers in the democratized union structure. Other fighters stepped forward to take their place.

Meanwhile, the picket movements were demonized by hysterical media campaigns. And the new UMWA leadership was betraying militant hopes.

The militant networks now needed a more sophisticated ongoing form of rank-and-file organization. It was not enough to have local officials leading one-off strikes from the shadows. The rank-and-file needed common long-term demands. They needed a recognized voice that could articulate a radical narrative among the miners themselves and then a larger arena of public opinion.

In important ways, “the crown lay in the gutter.” The cadre of the RU stepped forward to organize this new kind of organization. By mid-1974, our members were well embedded among District 29’s militants. Several respected activists came up with a petition demanding the right-to-strike — and invited us to join the planning. Their idea was to force the UMWA leadership to demand the legal right to strike in the 1974 contract negotiations.

Our RU leadership recognized the emergence of this demand as an important, maturing step for the struggle. We embraced their plan. And so we united with a dozen or so leading militants to form the Miners Right to Strike Committee (MRTSC).

Next came a fascinating debate within this new organization over exactly what the focus should be.

Was the goal mainly a new grievance procedure that included a local right to strike? Or did miners really need an open-ended right-to-strike that included large political issues — like Black Lung disease, outrageous state policy, or….?

Some miners assumed that federal injunctions were caused by company bribery, so they proposed that money be gathered to “reverse-bribe” the corrupt judges. We argued against this scheme — because it dangerously misunderstood how the capitalists actually controlled their legal system.

And a bigger question was raised: Should the MRTSC be focused mainly on inner-union contract discussions? Or did we expect to spread walkouts when locals were attacked — creating strikes for the right to strike itself?

We communists supported making demands for the immediate contract negotiations — but we were convinced that the MRTSC needed to be prepared to escalate if and when our contract demands were spurned.

The MRTSC was also a way we communists brought in some much-needed methods from the larger revolutionary movement. For example, wildcats had not previously produced leaflets explaining the issues behind big strikes. The very idea of using leaflets were controversial at the beginning — but soon proved its value.

The MRTSC produced broadsheet and manifestos during wildcats and at key moments during contract showdowns. Later we also organized press conferences, informational pickets, and car-caravans to new areas.

The RU’s organizational plan was to build “intermediate workers organizations” (IWOs) that would become cores of struggle that were “intermediate” between trade unions and our communist organization.

Our goal was never to “take over the unions.” Our RU cadre didn’t run for local offices. Our intent was to build a class-conscious, organized, country-wide force that could independently lead campaigns around cutting-edge political struggles, including structural racism, imperialist war, class-wide economic demands and ultimately power.

The MRTSC was quickly hooking up with militant local leaders one area after another within West Virginia. A new cohort of RU members started holding separate committee activities in District 17. Close supporters formed a third MRTSC in northern West Virginia, around Morgantown.

This MRTSC structure soon proved different from the previous shifting coalitions among local officials. It developed its own membership directly among active miners who weren’t as bogged down by local union responsibilities. The MRTSC contained no district officials or union staffers — though sympathetic folks at all levels slipped us inside info.

Within a few years, the national RU had developed political work in most basic U.S. industries. By 1977, we attempted to form a countrywide “National United Workers Organization” (NUWO) — that would bring together city-wide IWOs and early industry caucuses.

The MRTSC affiliated itself with that NUWO effort, at least on paper. Several of us toured the U.S. promoting the NUWO. I went on a speaking tour through the Deep South — from Greensboro to New Orleans.

Applying the Mass Line

Our ability to anticipate the great potential of this right to strike demand flowed from our application of the Maoist “mass line” concept.

The mass line starts with the insight that the masses of people must be themselves involved in making changes. With the people, seemingly impossible things can be achieved. Without connecting deeply to the people, small groups can accomplish little on their own.

This meant we needed to deeply investigate the felt needs among the people. The mass line then calls for synthesizing those scattered, spontaneous ideas we uncover with our own communist understandings about long-term goals. Taking the synthesized demands and analyses back out among the people enables the masses to recognize and embrace such plans as their own.

We recognized the “right to strike” demand as an important new creation of the most militant workers. We helped rework the idea, to break it free from UMWA contract confines, and free it to become a unifying demand inspiring mass struggle.

Our organizational plans were also informed by the mass line. We understood that the masses of people are inevitably quite diverse politically. And Maoism sorts such diversity into the categories of the relatively advanced, the intermediate and the backward. Our key organizational method was to unite the relatively small number of the advanced to win over the broad intermediate layers, and isolate the die-hard backward.

In short, we were working for an ongoing organized unity between communists and the advanced that could emerge as a new material political force — one that could actually influence and lead the broad intermediate in struggle.

Through that process, we could together neutralize hard-core backward forces among the workers (including corrupt company tools, hyper-conservative religious types, and active racists).

This Maoist mass line rejects the logic common within some left projects of confining our own political work to whatever could be immediately and easily understood by the intermediate.

The MRTSC became our main framework for uniting with the advanced among the miners to lead others in broad struggle against the system. At the same time, we needed to pursue our own work for the larger cause of communist revolution, especially among the advanced, but also in popular ways among the wider public.

This method required us to ask: “Who are the advanced? How do we identify them and connect with them?”

The early RU adopted a verdict that the advanced were active workers who developed the trust and leadership of their co-workers in the course of day-to-day struggles, even if such mass leaders may initially have significant backward and even anti-communist views.

Proceeding from that, we initially assumed that the militant cores of the wildcat strike movement would be where the advanced workers gathered. That’s why we had come.

Our experience quickly challenged these assumptions.

My partner and I lived in McDowell County where some large mines employed significant numbers of Black miners. Those mine locals (including my own) were often led by long-standing, heavily Black union cliques.

When I attended my first late-night strike rally, I got a look at the hundreds of militants kicking off the 1974 Gas Protest. I suddenly realized that the rally was all white. We were seeking to connect with the most powerful upsurge of workers in the country, and for some still-unknown reason, Black miners were simply not present within its active core.

Everywhere else in the United States, Black people had long formed the driving, advanced edge of radical politics, exemplified by the Black Panther Party and Detroit’s revolutionary Black autoworkers.

It was inconceivable to us that the advanced workers of southern West Virginia could possibly be all white — or that Black miners were somehow all among the intermediate.

Our early practice challenged our organization’s preconceptions. One moment drove this home.

As the 1974 gas strike became tense, a couple of men staggered into our late-night picket meeting badly beaten. They said a few Black miners had pistol-whipped them at Gary’s cleaning plant and then gone in to scab.

Some men within the picket meeting started shouting that we should go a nearby Black pool hall and fuck everyone up. One drunken voice shouted, “Time to go get the n*ggers.”

The rally had cracked open. One second we had this ferocious strike movement against the government, a split second later, it threatened to spin off a racist lynch mob!

The future of this movement obviously hung in the balance. Miners around me mumbled they were leaving if things went that way. I was the only comrade there that night, so I thought, “Fuck it. It’s up to me.”

I jumped on the back of a pickup and shouted that this racist plan was against everything we should stand for. It would destroy our struggle for years to come. Then I added I was going down to defend that poolhall — with anyone willing to go with me — and that we would shoot anyone attempting to attack the place.

The air suddenly went out of the racist loudmouths. The larger crowd fell silent for a moment. Then strike leaders went back to assigning pickets.

This was an eye-opening event for us. Clearly there were politically advanced, intermediate, and also quite backward workers present at all levels in the wildcat strike movement. And we now understood there must be significant advanced forces in the Black coal camps that were not currently present in the picket movement.

The active and advanced workers were not the same thing. They overlapped and coexisted within the picket movement. But we had to make distinctions for our strategic purposes.

The national RU’s practice was running into similar experiences. In the coalfields, we pursued our work among the miner-militants at the core of the wildcat strike movement. But we also developed revolutionary political projects that were not directly tied to the strike movement.

We organized public May First celebrations, starting in 1975, around revolutionary demands. We promoted May Day driving car caravans of 10 or 15 trucks through the coal camps, decked out with loudspeakers and banners.

We launched a bimonthly communist newspaper, the Coalfield Worker. We launched campaigns of internationalist solidarity — including a speaking tour of ZANU guerrillas from Zimbabwe in southern Africa. We brought miners and active women to meet revolutionary Iranians at West Virginia engineering colleges.

And we carried out postering and graffiti celebrating socialist achievements in Maoist China, and then exposing the capitalist restoration that followed.

We developed a loose division of labor along gender lines. Male comrades were working in mines and pursuing the MRTSC as a main area of work. Female comrades took the lead in our political campaigns, including producing and selling the Coalfield Worker.

Meanwhile, most of us were quite open and enthusiastic about our communist politics, with neighbors, co-workers, miner-militants, and (after a time) in public rallies and media interviews.

Revolutionary Outreach vs. Counter-Revolution

Within months of the Gas Protest, the miners’ movement faced a sudden crisis.

Charleston’s school board approved progressive new textbooks — which explored human experiences remote from cultural conservatism of many West Virginian coal camps. A militant movement rose to reject the schoolbooks. Influential fundamentalist churches mobilized against incursions of Black thought, women’s liberation, sexual freedom, abortion, and anything associated with progressive change.

Preachers decked out in three-cornered hats picketed mines along Cabin Creek. This pig strike started to spread through District 17 mines surrounding Charleston. Almost immediately, miners around the state contacted the MRTSC, asking if we should all join this strike. After all, the standing rules were: if a brother miner asks for help, you give it.

The newly-founded Heritage Foundation, new Religious Right networks, and the Klan sent cadre in to shape and lead this Textbook Protest. Suddenly, our still-fragile miner network collided head-on with organized counter-networks promoting rightwing cultural wars.

We successfully convinced our miner contacts to help to prevent this reactionary strike from spreading. But we also needed to publicly counteract this ugly eruption of racism, patriotism and fundamentalist religion. The MRTSC simply did not, at that point, have the common understandings needed to take the lead.

Our comrades in Beckley formed a close coalition with a radical group of Black veterans. Together we produced a newssheet exposing the Textbook Protest. It was widely circulated in the strike zone, among miners generally and in Black communities. I believe it helped contain that reactionary strike to one small area near Charleston.

RU and MRTSC members also crashed rallies in Cabin Creek where we denounced the whole anti-textbook thing, and physically confronted Klansmen.

Clearly the “traditional” miners’ respect for picket lines had limitations when controversial political issues were involved. The workers needed a class-conscious core to help identify which causes deserved support and which didn’t.

This episode gave us valuable insights about the views among our contacts regarding white racism, religion, women’s equality and more.

The Sexual Apartheid of Coal Camps

Appalachian coal fields imposed severe inequality on women. Coal operators hired only men for the mines (until the late 1970s). Male miners enjoyed the social life, close camaraderie and income of mine employment. Women were often confined to domestic drudgery, financial dependency, plus church activities. Men and women lived in separate worlds. Male supremacy and even wife beating were typically justified with Bible passages.

We communists tackled the creative challenge of involving women in both the struggle of employed miners and larger radical politics (including the liberation of women).

Meanwhile, this sexual apartheid impacted our own outlooks and relationships in ways we had not anticipated. Our comrades all held strong belief around women’s liberation. But, we were now in a world where the dramatic actions of male miners spontaneously took center stage.

Our fierce and sophisticated female comrades found themselves “on the outside looking in.” The male supremacy of the surrounding society crept into the outlook of male comrades and even tore at our marriages.

As the RU initiated explicitly revolutionary political work, our female comrades took the lead and also served as overall RU leadership. My partner Gina was an elected leader in the local Black Lung Association and helped organize a protracted militant struggle of mainly-Black women hospital workers.

Anti-communist Hysteria: Impact & Lessons

The moment our RU cadre emerged as strike leaders during the national 1975 “right to strike” wildcat, the authorities launched a ferocious anti-communist campaign to wipe us out. FBI’s mouthpiece-columnist Victor Riesel published a nationally syndicated exposé. He fingered individual comrades by name and crafted anti-communist talking points for reactionaries to repeat.

For the next years, campaigns of hysterical lies regularly erupted on the front pages of coalfield newspapers. One local daily printed a photo of me meeting publicly with a dozen miners. Reporters went to each person in the photo demanding that they denounce me or explain their support for communism. An editorial declared that I deserved a “bullet in the head.”

Top UMWA leaders launched a national campaign to denounce wildcats, the MRTSC, and communists. At one national convention, reactionary delegates demanded that the union use its anti-communist clause to expel us.

A federal judge sent two comrades to prison for distributing leaflets in defiance of his anti-strike injunction.

The LaRouchies held a press conference (as a non-existent “Labor Party”) and denounced the MRTSC as agents of Britain seeking to destroy the American coal industry. Coalfield press headlined the absurd claims.

Teams of Moonies cruised beer joints across southern West Virginia distributing a tract denouncing coalfield communists as enemies of God.

This protracted, red-baiting hysteria repeated one refrain over and over: the moment miners realize that there were communists among them, they would instantly turn on us — force us to flee or die.

I think the authorities truly believed this. It had been their COINTELPRO experience during the McCarthy period.

The red-baiting did unleash knots of rightwingers to launch violent attacks on our comrades and close supporters. Comrades experienced late-night death threats. Carloads of drunk rightwingers took potshots at comrades’ homes.

Several comrades were jumped and beaten. One had his front teeth knocked out. A bomb blew up the garage of one couple. One close supporter suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be hospitalized. Everyone around the RCP and MRTSC lived with a real danger of assassination.

I was, with another comrade, leading a daytime strike rally of about 400 miners in a roadside park. Four men showed up waving a noose and shouting it was time to “kill the communists.” We took them on and refused to back down. After an intense standoff, they got no support from the crowd and left.

The local newspaper published a lurid lie: that one of us had been hoisted by the noose. The rope broke and we supposedly ran for our lives. Their lie was reprinted across the country.

Here is the important truth: The authorities simply failed to drive us out.

The MRTSC continued to operate through all the confusion and raw terror. We organized rallies and press conferences during the strikes. MRTSC literature was distributed on a coalfield wide scale. We expanded our networks of collaborators. We went on to play a prominent successful role in the looming 1978 contract strike.

The coal companies never succeeded in firing any of our communist comrades — though they tried over and over.

The Miller clique was unable to carry out our expulsion from the UMWA.

Why did they fail?

First, the authorities never grasped how open our cadre had been about communism — circulating communist materials everywhere we went. When the FBI “exposed” us, everyone around us in communities, mines, and the MRTSC already knew what we stood for.

Second, I’m proud to say that our cadre proved extremely tough and optimistic. Only one comrade dropped out and left.

Third, the authorities were stuck in the McCarthyite ’50s. They never understood how much more conscious and alienated the miners of our ’60s generation were than their parents.

Fourth, most important, it became clear that many thousands of people took actions — often unseen and anonymous — to protect us from being crushed. They did this from their own political viewpoints, not usually from ours. Many supported the intense resistance we were helping to lead.

Gina and I felt as if we were “stage-diving in the dark.” Living under threat, we launched ourselves out into the darkness over and over. We experienced the eerie, wonderful feeling of being held up by countless unseen hands.

One example: A local church started attacking my home and family. Our tires were slashed. Friendly neighbors were threatened. Things were escalating toward violence.

Then two Pentecostal preachers who I’d worked with asked to address the church. From the pulpit, they made a passionate defense of Gina and me, our work and our motives. The congregation split in two. And the attacks stopped.

I learned these details only much later. Much was happening under the surface — all across the coalfields.

Our communist project recruited some independent radicals who had also entered in the mines.

One young coal miner who joined had been the bodyguard for Arnold Miller during his MFD election and then worked with the United Farm Workers in California. These broader experiences that helped fuel his attraction to communist politics.

But in general, that leap from militant trade unionism to revolutionary communism proved difficult for even our closest, long-time co-conspirators.

Over the decade we worked closely with many non-miner progressives — who formed the Miner Support Committee (MSC) during the 1978 contract strike. About 50 people actively built the MSC including radical lawyers and academics. They created a free clinic for strikers and raised funds to print full-page “Vote no!” ads in coalfield newspapers.

We also formed an alliance with farmers from the American Agricultural Movement — who showed up with tracker-trailer convoys packed with food for hungry strikers.

At the same time, the RCP (Revolutionary Communist Party, the renamed RU) and its many IWO groupings organized classwide support for the miners across the U.S. building toward a national support march through Charleston.

Endgame

The story of how the upsurge ended can’t fit here.

The very short version is that monopoly capital rules society. The U.S. industrial heartland was plunged into rustbelt devastation as capital restructured itself globally.

When the ruling class concluded they couldn’t tame or crush the miners, they gradually shifted half of coal production to distant western strip mines. Appalachian coalminers were hit with massive layoffs immediately after the 1978 strike. And when the full impact of that sank in, the miners’ organized resistance drained away.

Our strikes and struggles keep our oppressors from reducing us to a “mass of broken wretches” (as Karl Marx puts it). And, at the same time, that resistance can serve as a valuable school of war — helping us to prepare and carry through the actual overthrow of this heartless system.

See Cosmonaut interview with Mike Ely. His email is mike.ely.0501@gmail.com

March-April 2022, ATC 217