Against the Current, No. 217, March/April 2022

-

Roe v. Wade: Blood in the Water

— The Editors -

Teamster Election: New Openings, Real Challenges

— Barry Eidlin -

Billions for Philippine Military & Police

— John Witeck -

bell hooks -- Fiery Black Feminist

— Malik Miah -

In the Classroom: Reparations Won

— an interview with William Weaver & Lauren Bianchi -

The British Labour Party's Quest for the Past

— Kim Moody - Free Leonard Peltier Now!

- Stop Thief!

- International Women's Day

-

Poland: Women's Mass Protests

— Justyna Zając -

Intersectional Feminism

— Alice Ragland -

Lives of Enslaved Women

— Giselle Gerolami -

Challenging the Comfortable

— M. Colleen McDaniel - The '60s Left Turns to Industry

-

Introduction

— The Editors -

The Movement, the Plants, the Party

— Dianne Feeley -

Miners Right to Strike Committee

— Mike Ely - Reviews

-

Times of Rebellion

— Micol Seigel -

New Light on the Young Stalin

— Tom Twiss -

A Russian Civil War Chronicle

— Kit Adam Weiner -

Art Overoming Divisions

— Matthew Beeber - In Memoriam

-

Mike Parker (1940-2022)

— Dianne Feeley

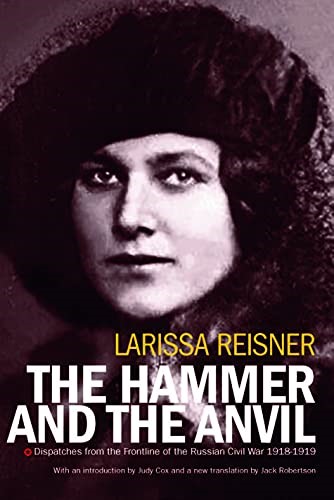

Kit Adam Weiner

The Hammer and the Anvil:

Dispatches from the Frontline of the Russian Civil War, 1918-1919

By Larissa Reisner, translator Jack Robertson.

London: Bookmarks Publications, 2021.

THE HAMMER AND the Anvil brackets 100 pages of Larissa Reisner’s eyewitness reports from the Red Army front from 1918 to 1919, when the author covered the Russian Civil War for Bolshevik newspapers, with essays about Reisner and an excerpt from Trotsky’s autobiography describing the same events.

Reisner had lived parts of her early life in Germany and eastern Europe, and was a dedicated Bolshevik when the Russian Revolution broke out when she was only 22.

Although it is a short work, it is difficult to read The Hammer and the Anvil without feeling a sense of profound tragedy over a talent lost at such a young age. Reisner had great literary potential and a knack for revolutionary journalism. All of that disappeared when she died of typhus in 1926 at the age of 30.

Reading her news dispatches, the reader is struck with her literary abilities. She fused her reportage with poetic devices to capture both the events that were newsworthy and the feelings they evoked in those on the scene. On the eve of the Red Army retreat from Kazan, an early Bolshevik setback, she writes:

“It’s a strange feeling to be moving about in an unfamiliar building with windows and doors slammed shut knowing full well that a battle to the death is about to take place in this godforsaken hotel. It’s a racing certainty that someone will be killed, some will survive, some will be taken prisoner. At such moments, all the words and all the rationalizations that help preserve your presence of mind go out the window. All that remains is an acute, penetrating sorrow — and underneath it, barely perceptible, a disorienting question: whether to flee or stand your ground. In the name of what? Face screwed up, choking with tears, the heart reiterates: stay calm, don’t panic, no humiliating exodus.” (36-37)

The Red Army, along with much of the population of Kazan, fled to Sviyazhsk in 1918. However, Reisner suspected that her husband, the Bolshevik Fyodor Fyodorovich Raskolnikov, had been taken captive by the conquering Whites and she attempted to return to Kazan to free him.

When a White officer recognized her she fled with the help of a horse-pulled cab driver who sympathized with the Reds. The Russian poor, she wrote, “saved people like me, humbly and resolutely, just like they saved thousands of other comrades scattered all over the Russian highways.” (62)

The Red Army soon regrouped at Sviyazhsk, also along the Volga river and just south of the critical city of Nizhny Novgorod. At Sviyazhsk Reisner observed the attempt to fuse military discipline with revolutionary culture.

“Not being average became the norm. It became obligatory for all. That meant adopting the best, most brilliant tactics conceived by the masses in the most intense and creative moment of the struggle. Whether it be a major or minor issue, no matter how difficult or confusing — such as the division of labor between the members of the Revolutionary Military Committee — or the quick, friendly gesture, with which a red commander and his soldiers are expected to greet each other, on equal footing, even though both are running somewhere on business — all this had to be witnessed first hand, memorized, and then reintroduced into the masses for general use. And when it didn’t work, it creaked or was confusing — the problem needed to be assessed, addressed or coaxed along, like a midwife would do during a difficult labor.” (80)

Up Close Descriptions

Reisner’s reports will not suffice for those who want a comprehensive picture of the Russian Civil War. However, she does offer poignant descriptions of what the war looked like up close.

She brings to life working-class townsfolk who supported the new Bolshevik government and highlights the terror the White armies inflicted on the population. But the reader who has read nothing else about the civil war will have difficulty contextualizing the stories she poetically conveys.

Nor does this work address modern debates about the early Soviet republic or the early Bolshevik debates about military structure and strategy. At one point, however, she offers some insight into her own thinking on the question of capital punishment and the treatment of deserters.

At Sviyazhsk the Red Army, under Trotsky’s personal guidance, was preparing a counter-attack on Kazan. The Whites then launched a powerful preemptive counter- strike nearby, killing civilians and livestock. Ironically, the Whites ultimately overestimated Red strength at Sviyazhsk and retreated when they might have dealt a fatal blow.

Before that moment there was panic among the Red ranks and several Communist Party members fled. The Communist deserters were captured, tried and executed. Thinking aloud about whether their lives should have been spared she opines:

“To begin with, the whole army was saying that the Communists were cowards, that the law didn’t apply to them, that they could desert with impunity whereas an ordinary Red Army soldier would have been shot like a dog …

“In the eyes of the entire army, which was preparing to make such a great and bloody sacrifice for the Revolution, this would not have been possible if the Party itself, on the eve of the Kazan assault — in which hundreds of soldiers would inevitably be killed — had not made clear that it had the courage to apply the hard-hitting laws of fraternal discipline in the Soviet Republic to its own members.” (76-77)

In The Hammer and the Anvil Reisner did not spell out her thinking beyond that. Marxists today who are interested in exploring the questions of what revolutionary ethics might look like under a revolutionary democratic regime will not find persuasive arguments in this collection. Nonetheless, Reisner’s observations open a window into the thinking of at least some Bolsheviks on the scene at the time.

The Hammer and the Anvil opens with a useful essay by Judy Cox on Reisner’s short life. It continues with a short essay titled “The War Against the Bolsheviks” by Jack Robertson, who also translated Reisner’s reports.

College and high school teachers may find this chapter useful because of the quotations it provides highlighting the anti-semitism both of the White officers and their Allied supporters in the west.

The book concludes by reprinting the chapter on the events at Sviyazhsk and Kazan from Trotsky’s My Life. This inclusion was likely intended to show that Reisner’s account tracked with that of the Red Army’s top commander. It also contains a handful of synopses of the lives of some lesser-known rank-and-file revolutionaries who played parts in the sagas Reisner describes.

Reisner’s reports compiled in this collection indicate a sharp mind and impressive tential. Hers was one of many lives cut short by war and disease. One wonders what she might have accomplished if given the chance to grow intellectually.

March-April 2022, ATC 217