Against the Current, No. 215, November/December 2021

-

The Rising Price of Insanity

— The Editors -

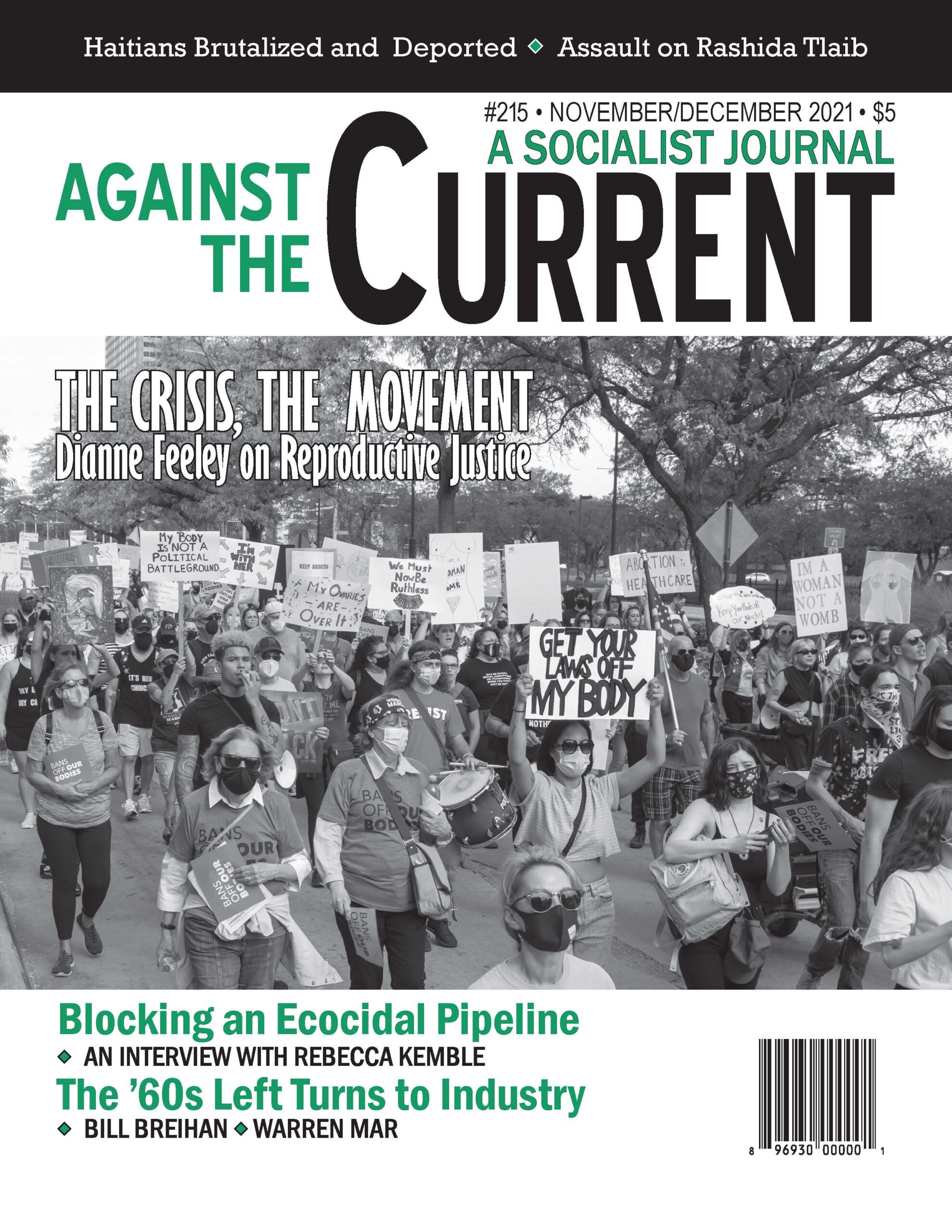

Reproductive Justice on the Line

— Dianne Feeley -

Teenagers Are Children, Not "Bad Seed"

— an interview with Deborah LaBelle -

Blocking an Ecocidal Pipeline

— an interview with Rebecca Kemble -

The Ecosocialist Imperative

— Solidarity Ecosocialist Working Group - Hitting the Bricks for "Striketober"

-

The Assault on Rashida Tlaib

— David Finkel -

Nicaragua, as Elections Approach

— Margaret Randall -

Crime Scene at the U.S.-Mexico Border

— Malik Miah - Revolutionary Tradition

-

The '60s Left Turns to Industry

— The Editors -

The SWP's 1970s Turn to Industry

— Bill Breihan -

Organizing in HERE, 1979-1991

— Warren Mar - Reviews

-

Preserving Voices and Legacies: Jazz Oral Histories

— Cliff Conner -

On COVID's Death Toll

— David Finkel -

Reflections on Party Lines, Party Lives, American Tragedy

— Paula Rabinowitz -

Reclaiming the Narrative: Immigrant Workers and Precarity

— Leila Kawar -

Envisioning a World to Win

— Matthew Garrett -

Sharing and Surveilling

— Peter Solenberger -

A Labor Warrior Enabled

— Giselle Gerolami

an interview with Deborah LaBelle

AT THE START of last year, 1465 people incarcerated in U.S. prisons were serving sentences they had received when they were children—some as young as 14. The combination of public pressure and civil rights lawsuits resulted in U.S. Supreme Court rulings curtailing these sentences. Today 25 states and the District of Columbia have banned life sentences for youth.

Data indicates that of those youth sentenced to life without parole, more than three quarters witnessed violence on a regular basis in their homes. Nearly half were physically abused, with that figure rising to 77% of girls sexually abused. While racial data are incomplete, it appears that about 62% of the youth imprisoned under a life sentence are African American.

Dianne Feeley interviewed Deborah LaBelle, a civil rights attorney, professor and writer. She has been lead counsel in more than a dozen class action cases that challenged policies for incarcerated people, particularly youth. Formerly she directed the Juvenile Life Without Parole Initiative for the ACLU of Michigan and coordinated Michigan’s Juvenile Mitigation Access Committee.

LaBelle is the author of chapters “Women, the Law and the Justice System: Neglect, Violence, and Resistance” in the volume Women at the Margins: Neglect, Punishment and Resistance (Routledge, 2002) and “Ensuring Rights for All: Realizing Human Rights for Prisoners” in Bringing Human Rights Home (Praeger Press, 2008). She was the consultant to the documentary, “Natural Life” (2014), that highlighted the inequities in the U.S. juvenile justice system by looking at five cases.

LaBelle has not been able to review the text of this interview.

Dianne Feeley: Could you speak about the significance of the U.S. Supreme court decisions that addressed life without parole sentences for youth convicted of homicide?

Deborah LaBelle: Do you mean the Miller v. Alabama (2012) and Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016) decisions? If so, let me fill in the background to those decisions.

Before 2010 a group of us including Bernadine Dohrn, who’s been working on children’s rights a long time, Kim Crenshaw and Alison Parker from Human Rights Watch and Ben Jealous from Amnesty International got together at Open Society Foundation (OSF), the Soros offices where I was a Senior Soros Fellow.

I had just been interviewing Michigan prisoners at youth and adult prisons. While I knew Michigan didn’t have the death penalty, I had no idea about the number of youth who had been sentenced to life without parole — or about what that really meant. When I compiled my survey I found out there were hundreds in this situation and worked with the ACLU to put together a report, “Second Chances.”

After that, I started getting data from other states. When we met at OSF, we agreed to coauthor a monitoring report. We called it “The Rest of Their Lives” because when we pulled together focus groups, we discovered that when people heard “life without parole” they really thought, “Oh, that means people will have to serve seven years before applying for parole.” The majority had no idea that children as young as 14 were being incarcerated until their death.

Massive Disparities

Our monitoring looked at what was happening around the world. It was clear that the United States, along with Israel in its treatment of Palestinian youth, were exceptions in how children were sentenced. While the United States was out of step, we were worried that Australia and Britain were looking to the United States to possibly adopt such punitive sentences.

Because of the huge racial disparities in sentencing, we developed a plan to go to the U.S. Human Rights Commission as well as to the United Nations, where we would address the Committee to Eliminate Racial Discrimination as well as the Committee Against Torture. We would ask for observations from all the major human rights bodies at the United Nations, chastising the United States for violating of a number of treaties.

We would petition the Office of American States, again stating that such sentences were a violation of the treaties the United States had signed and ratified.

We agreed to try a litigation approach that began with the harshest sentence handed out for homicides: life without parole. Although we wanted to pull children out of the punitive prison system altogether, we wanted a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that would recognize kids arrested were children, that we had failed them as a society and now we were punishing them to cover up our own failures. To recognize that the child is a child would start the ball rolling toward examining youth incarceration for lesser offenses.

I was in trial at the time the Miller case was argued in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. I remember Bernadine calling me from the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court. She said she knew we’d won because every single justice, except for Scalia and Thomas — who said nothing — used the word children, not convict, offender or prisoner.

Once you recognize that these are children, it’s hard to say, “We’re going to take a child and put them in a cage until they die.”

The Court understood the brain science — that is, children have not fully developed their control impulses. Additional mitigating factors include growing up under difficult circumstances and being subject to abuse.

The Court understood that children lack experiences that enable them to make the best choices. Others are runaways who feel they have no choice.

We reported that the majority of youth who did not have their own counsel, and were assigned one, were often provided with inadequate lawyers. Some simply lacked training in handling criminal cases while others were so inadequate they were subsequently suspended or disbarred.

So if the family couldn’t afford a lawyer, the kids got the worst representation. But while the Court did mention that fact in their decisions, they ignored the racial component, as courts have done for decades. While various factors were taken into consideration, the work we did to document how life without parole was a racially discriminatory sentence went unmentioned.

The reality is that life sentences were disproportionately given to children of color, who were viewed as “bad seeds.” The super-predator myth continues: they receive the harshest sentences, the least resources in their defense and are less likely than white youth to be placed in juvenile treatment facilities. Another factor at play is that when the victim is of a different race, the sentence is more severe.

The Miller v. Alabama decision was an amazing breakthrough – but it didn’t abolish the sentence of life without parole, it only said it should be very, very rare. The 2016 Montgomery v. Louisiana case was argued in order to make the decision retroactive.

Some states, like Michigan, had said, “Okay, we won’t sentence youth to life without parole in the future, but the 367 who are currently serving that sentence are ‘stable.’” But Justice Kagan in effect noted, “We just said that is cruel and unusual punishment. You can’t continue; each case must be re-examined.”

Actually, the Supreme Court’s decisions were bizarre because they retained the sentence for the very rare child who “exhibits such irretrievable depravity that rehabilitation is impossible.” Absent that, there must be a meaningful opportunity to be released. What judge or psychologist can determine that a child should be thrown away? No one can determine what someone will become!

DF: What has been the impact of those decisions?

DL: In Michigan about 250 individuals have had hearings, with nearly 150 released. Because in Michigan the life without parole statute requires serving a minimum of 25 years before seeking parole, others who have been re-sentenced are awaiting parole.

Among those released there has been no recidivism. So despite the reality that many grew up in incredibly dysfunctional homes and have been greatly harmed, this group, who shouldn’t have been imprisoned so long, is doing amazingly well.

Child Abuse

Last year we settled a case against the Michigan Department of Corrections for youth who had been placed in adult prisons. Not only is life without parole a horrific punishment, but they were then preyed upon by both adult prisoners and correctional staff. They had also been subject to solitary confinement. The state was forced to pay the second highest settlement ever, $80 million, because of egregious harm.

If you put a child in a closet for three days, you would be subject to child abuse. Here the state is putting youth in harm’s way, and in cages and solitary confinement for months. No child should be put in a prison; no child should ever be prison for anything.

And if this shouldn’t be happening to children involved in homicide offenses, then we need to look at all the other children, who are arrested for home invasion, for drugs, for larceny and sentenced to adult prisons. It’s a destructive and senseless way to hold children “accountable” for breaking the law.

DF: What were the deficiencies of those two decisions?

DL: They didn’t totally abolish life without parole on the basis that it is cruel and unusual punishment.

I’ll use Michigan as an example: prosecutors in certain counties decided that they would re-sentence once again to life without parole. Instead of being a rare sentence, the prosecutor in one county sought life without parole in 40 out of the 43 cases.

Then there is the racial disparity: the majority of those re-sentenced to life were people of color. Geographic injustice is a large problem as well, when prosecutors and judges in certain counties refuse to follow the Supreme Court guidelines.

How arbitrary is that, when just one prosecutor or judge has this power? Fortunately, some counties are electing more progressive prosecutors.

Michigan’s Constitution talks about “cruel or unusual punishment,” which means legally only one but not both elements must be proven. When a punishment becomes “unusual,” it is subject to problematic implementation. It’s not a standard punishment, but only happens here or there — it’s almost archaic.

For the evolving sense of decency, which is what the Eighth Amendment talks about, we need to move away from these sentences entirely. But re-sentencing is subject to arbitrary implementation by judges who simply don’t believe in following the Miller and Montgomery decisions. Of course it also leads to continuing the troubling racial disparities in sentencing.

The majority of states have now abolished life without parole as a potential sentence for children under 18. This happens mainly through legislation or state court decisions. Certainly we will keep litigating until people recognize that every person convicted of this sentence as a child deserves an opportunity to present their case: they are no longer a danger and should come home.

I think the sentence itself should have been abolished. Children’s cases should be handled in a child’s court.

Instead there is an arbitrary and unfair system. Why 25 years before you have an opportunity for parole? It’s not like anybody studied things and said, “After 25 years of prison programs you are rehabilitated.” It’s pulled out of the air. It has no rational basis. Is 25 years harsh enough so that we feel good about vengeance?

The majority of adults who commit homicides are charged with first-degree murder. The vast majority, I think it’s 96%, take a plea, generally to second-degree murder. If convicted of second-degree murder or given a life sentence, the adult has an opportunity to go before the parole board after 15 years. That means adults who commit the same offenses as children have an opportunity to appeal for parole 10 years earlier.

Need for Transparency

DF: U.S. society has become more aware of how unaccountable police departments are. What about the rest of the legal system, the prosecutor’s office and the courts?

DL: There needs to be transparency for all prosecutors and judges. We don’t know what goes on. Prosecutors have broad discretion in bringing or dismissing charges, suggesting sentencing guidelines, offering a plea or dismissing charges. Judges also have discretion in accepting the prosecutor’s charges and sentencing guidelines.

We need transparency not just to find the people who are innocent,* but those who have gotten excessive sentences whether because of misconduct on the part of police, prosecutors or were given a racially-tinged sentence.

Citizens for Racial Equality (CREW) in Washtenaw County did an amazing report on racial bias in the county’s legal system. Their August 2020 report, “Race to Justice,” studied the prosecutors’ office and county court. The report identified a retired prosecutor who routinely added felony firearm charges, a mandatory two-year sentence, on top of the original charge for the youth of color who were arrested.

It also found a judge who sentenced African Americans to longer prison terms for the same crimes whites were convicted of committing. Look at what the prosecutor is doing and then follow through with the judges and the sentencing.

CREW’s report advised monitoring these legal institutions and launching an oral history project so that people can talk about what they went through with the larger community. Without this transparency we don’t know what to fix. But once we see how prosecutors charge people differently based on race, we can change it.

Today prosecutors can charge people with anything. Then they go before a judge and we don’t know the basis of their sentencing. They don’t publish their opinions very often. And once judges are elected, as incumbents they are easily reelected.

Most countries do not have the level of incarceration the United States has. In Michigan the Department of Corrections currently has a yearly budget of more than two billion. We have no idea what they are doing. What programs do they have and how successful are they?

If a corporation had to pay out $80 million because of a complete failure to protect children under their care, we would not consider the enterprise successful. A few years earlier they had to pay out a million dollars because their staff was assaulting women. Yet every year the Department of Corrections gets an increase in their budget. Their budget is larger than our state’s education budget.

DF: You spoke about the $80 million settlement you won for people who had been abused as teenagers placed in adult prisons. What was the state forced to do as a result of this victory?

DL: When we started the suit, there were over 200 children at any one time in Michigan adult prisons. We forced the Department of Corrections to end the practice — no children under 18 in adult prisons. Currently there are six but by the end of the year there will be none.

We developed a different way of reporting abuse and eliminated solitary confinement for youth. We’re still overseeing the implementing of programs including making counseling available and setting up trauma centers. There are a lot of people in prison who are suffering from PTSD, and that includes youth.

Youth are to be processed and kept completely separate, only overseen by staff trained as youth counselors. We are also pressing for defining the transition from childhood to adulthood at 21, not 18, and having those between 21 and 26 in a separate group as well.

In some European countries, the person running the facility is held accountable for the recidivism rate. Instead of blaming the person being released and unable to find their legs, society should be asking questions. How did the program that supposedly prepared them fail? Was there a history of prison abuse or neglect?

The director and the department should be held accountable. Succeeding doesn’t just mean preventing an escape, it means helping people to be good citizens.

For years the state of Michigan was releasing people without so much as an ID. It’s very easy to get people an ID and their social security number before they’re released. Yet it took us years to get the department to act on our simple demand.

Seriously, what do you think will happen when you release people with felony records, no ID, no funds, et cetera, et cetera?

Kids coming out of prison are subject to stringent reporting. They have a lot of rules that make it almost impossible to do. They have to go once a week and take a drug test whether or not they have a history of using drugs. They have to get to places where the bus doesn’t go to take that drug test.

They don’t have cars and they don’t have money, so they are often forced to beg for rides. I’ve sent Uber to pick them up so they can get there. If they don’t, they can end up back in prison. Reporting is often random so sometimes they have to leave work to get there on time. Nothing is made easy.

Kids now 21, whose offenses have nothing to do with alcohol, are prohibited from working in any place that serves alcohol. They can’t even work in a Friday’s restaurant. The limitations are so severe and so thoughtless.

Probation is not a system that recognizes the difficulties people might have. It’s insanity to have arbitrary rules.

DF: Isn’t that because we have a throwaway culture? Prison is just one more mechanism for throwing people away.

DL: Let’s not forget we also have the prison industrial complex. We have a lot of people who are invested in having a robust level of incarceration.

When you look at the low level of youth recidivism in the Scandinavian countries, it seems to boil down to their understanding that children are children, and should be treated under international standards, consistent with their status as children.

They want youth to succeed in life. That is a real difference — we just don’t hear that here. Here youth are to “behave,” meaning they should accept their punishment. That’s not a good understanding of what it takes to succeed. And there are a lot of things that make it almost impossible.

We must ask every politician running for office: “What are you doing to build accountability across the legal system? What are you going to do to reduce the inequality and trauma the legal system represents? How can we insure a seamless transition from punishment to reintegration?”

*As of October 2021 the Michigan Innocence Project has presented evidence that led to the release of 29 people from prison.

November-December 2021, ATC 215