Against the Current, No. 215, November/December 2021

-

The Rising Price of Insanity

— The Editors -

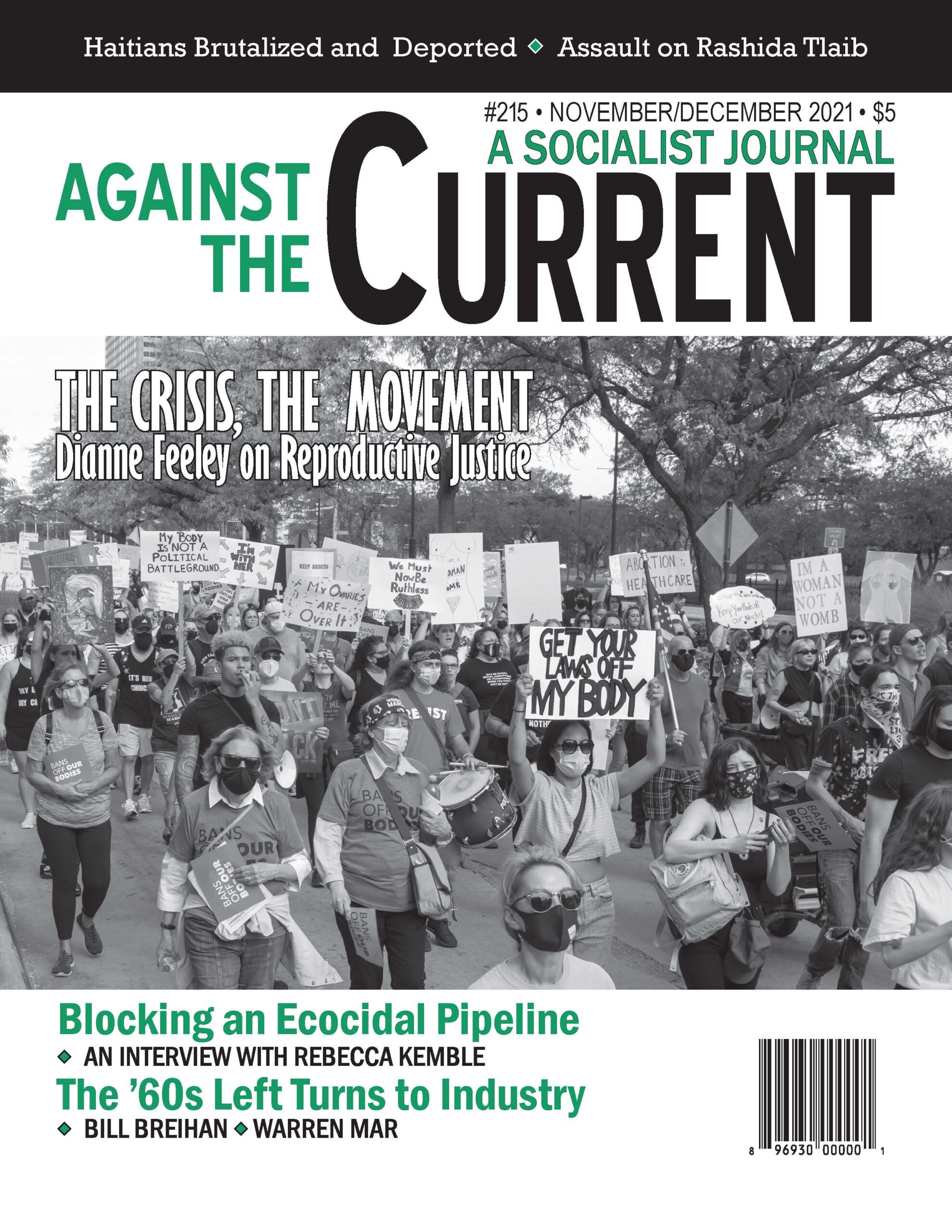

Reproductive Justice on the Line

— Dianne Feeley -

Teenagers Are Children, Not "Bad Seed"

— an interview with Deborah LaBelle -

Blocking an Ecocidal Pipeline

— an interview with Rebecca Kemble -

The Ecosocialist Imperative

— Solidarity Ecosocialist Working Group - Hitting the Bricks for "Striketober"

-

The Assault on Rashida Tlaib

— David Finkel -

Nicaragua, as Elections Approach

— Margaret Randall -

Crime Scene at the U.S.-Mexico Border

— Malik Miah - Revolutionary Tradition

-

The '60s Left Turns to Industry

— The Editors -

The SWP's 1970s Turn to Industry

— Bill Breihan -

Organizing in HERE, 1979-1991

— Warren Mar - Reviews

-

Preserving Voices and Legacies: Jazz Oral Histories

— Cliff Conner -

On COVID's Death Toll

— David Finkel -

Reflections on Party Lines, Party Lives, American Tragedy

— Paula Rabinowitz -

Reclaiming the Narrative: Immigrant Workers and Precarity

— Leila Kawar -

Envisioning a World to Win

— Matthew Garrett -

Sharing and Surveilling

— Peter Solenberger -

A Labor Warrior Enabled

— Giselle Gerolami

Matthew Garrett

Revolutions

Edited by Michael Löwy

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020, 540 pages, $40 hardback.

EVERY READER SHOULD buy this book immediately, or rush to the library to find it. But they should do so in a spirit of unsparing scrutiny. Our revolutionary genealogies sustain us, above all in dark times, but the passion for changing the world is rightly paired with the cold eye of evaluation.

One risk in uncritically embracing the iconographies and image-repertoires of the past is that they can short-circuit true historical understanding, and therefore foreclose clear political thinking. The reappearance of Revolutions raises difficult questions for a revolutionary reader today.

First, one has to say that in reissuing Michael Löwy’s wonderful gathering of archival photographs and essays, originally published in French in 2000, Haymarket Books has once again done a great service both to the left and to anyone interested in history.

The book comprises a general essay on the photographic history of revolution, and individual chapters on the Paris Commune (Gilbert Achcar), the 1905 Russian Revolution (Achcar), the October Revolution (Rebecca Houzel and Enzo Traverso), the Hungarian Revolution (Löwy), the German Revolution (Traverso), the Mexican Revolution (Bernard Oudin), the Chinese Revolutions of 1911 and 1949 (Pierre Rousset), the Spanish Civil War (Achcar again), and the Cuban Revolution (Janette Habel), as well as a concluding essay and updated 2020 postscript by Löwy and a useful general bibliography.

It is a treasure trove and necessary book: an aesthetically beautiful collection of text and image, an exhilarating immersion in the revolutionary 20th century, a rich reflection on the status of the photographic image as a historical source, yet — not least — a discomfiting irritant for would-be revolutionaries in the churning yet oddly static situation of the contemporary Global North.

The unease is real, and it provokes some concern. What exactly did Haymarket think they were doing in republishing this text in 2020? Is Revolutions an antiquarian exercise? Surely not for the comrades at Haymarket, to say nothing of Löwy and his authors, all of whom share unquestionably leftist commitments.

Yet one has to say — with regret — that these days almost everyone, even many of the revolutionaries, in the advanced (senile) capitalist countries seems to agree in practice that revolution is permanently off the table. One can disagree (as I do) with this seeming consensus, yet also recognize our situational limits.

Looking Back and Ahead

On the left, a new social democracy has flowered during the post-Occupy decade under various labels. Thrillingly for many of us, the words “socialist” and “communist” circulate more or less freely once again (not only as slurs from the right), but the price of legitimacy seems to have been amputation of class struggle as strategy or even recognizable fact of social life.

The gravity of the Democratic Party and its international ilk has been admirably resisted by a vibrant and crucial, if politically ineffectual, set of extra-parliamentary movements. Among these we might include (among others): the brilliance of the Movement for Black Lives, which has been accompanied by an increase in the police murder of Black citizens and metastasizing of anti-Black racisms across the United States; the French gilets jaunes, now draining toward the bottom of the nationalist Macron-Le Pen-Zemmour sink; and Extinction Rebellion, boldly stating the obvious without any discernible effect on UK carbon emissions.

In the United States, emblematically, the troglodyte petty bourgeoisie has emerged from the darkness of “the heartland” into the glare of the national spectacle, but theirs is of course no revolution at all (January 6 notwithstanding), merely a vision of the radiant future as a whites-only shopping mall: more of the silent-majority same, with enhanced viciousness.

The year 2020, in short, was both an intensification of the post-History year 2000 and an alien context for a book on revolution. In his brief postscript to the new edition, Löwy cites the Arab Spring, the Democratic Confederation of Northern Syria, the leftist governments of Latin America, the Indignados and Yellow Vests, the youth climate protest, and the Movement for Black Lives as indicators that, as he puts it elsewhere in the book, “[h]istory is a long way from ending.” (519)

All these are, he notes, exceptionally fragile, but he also closes with a rather wistful note on the United States: “Black, brown, and white united in a popular rebellion without precedent since the 1960s. Is this the sign of a coming revolution, or just the latest expression of the subaltern’s rage against the system? The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind…” (532)

It’s a funny way to end this particular book, at this time, made indeed even more surprising by its author’s generational wisdom, which one might have thought would preclude the sentimental reference to ’68. (Activists in the movements, anyway, might prefer a citation of Kendrick or H.E.R. to Dylan.) Absent here is historical perspective on the conjuncture; even BLM is taken to be a second performance of the 1960s.

But just like Michael Löwy’s revolutionary blues, I’m afraid the joke is on us: there’s nobody even here to bluff. A revolutionary constituency must be assembled. To do so, the glimmers of History we might identify in our 21st century will need to be painstakingly analyzed and then compared, with real rigor, against the revolutionary balance sheet of the past.

One can identify with Löwy’s own political position — as I myself more or less do — and also fear that his evocative lines risk mystifying our own history. Dissevered from the pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will is — as Gramsci taught — stupidity.

That pessimism must be applied to the past itself. Doing so is one way in which we constitute history as an object of understanding and intervention: the way we generate one long narrative from long-gone events, linking them up (in a “moment of danger,” as Löwy’s much-admired revolutionary thinker Walter Benjamin put it) to illuminate our present.

If revolution mattered in 1871, 1917, 1949 and the rest, it is because it matters now, in the particular conditions within which those struggles — defeats and victories alike, which as often as not dialectically shift their valences — have come to bear on (to pressure, to shape, to set limits upon) subsequent history. This is not shallow presentism, but rather, as Benjamin insisted, the signature of historical materialism.

Another way to put this is to say that 1917 was not complete in 1917, or 1989; our task is, in part, to understand better than the actors themselves what their actions have meant, and can mean, for the ongoing struggle for freedom. Löwy himself has always taught this lesson.

Revolutions gestures toward instruction in this regard, but its accent is on the formal problem of representing revolution — in particular, the dialectical tension between text and photographic image. Before turning to that essential question, it is worth dwelling on a preliminary matter: what, precisely, unites the ten historical events chronicled in this book?

Given the extensive and often excruciating arguments within Marxism about the question of revolution, the relation between bourgeois and proletarian revolutions (including, significantly, the controversy over the validity or applicability of the notion of “bourgeois revolution”), and the troubled sequels to these events, some rationale for the portfolio is wanted but lacking.

The watchword of this volume is Trotsky’s: “the most indubitable feature of a revolution is the direct interference of the masses in historical events” (History of the Russian Revolution, quoted on page 16). But even a devoted reader of Trotsky should notice two points that bear on this book.

First,, the masses are always pressuring and determining events, and this view is axiomatic to a conflictual, class-struggle based account of history. What’s at stake, then, is a cleaving of Trotsky’s own language, which inherits a pre-Marxist notion of “event” (the kind of episode that makes it into the history books, say) and sews it onto a Marxist narrative of socio-political upheaval.

That concern points directly to a second: namely, that Trotsky’s rough-and-ready category of revolution elides the Marxist distinction between political and social revolution, and therefore seems to confuse our thinking more than help it. Are Zapata’s adventures analogous to the collective effervescence of the Paris Commune? Are the political lessons of Lenin’s strategic genius concretely related to the united front of the Spanish Civil War?

The history is internally contradictory, to say the least, and the book does not effectively suggest ways for the uninitiated comrade to find the way through a rather dangerous political labyrinth.

Representing History: Text and Image

What it fails to deliver in social history, Revolutions gives in its form of representation. This is its real achievement, and it also promises a lot for today’s revolutionary readers. Above all, Revolutions invites scrutiny by creating challenges to its own use. It is not a book for simple reading.

Each section begins with an essay, which is followed by a chronology of events; the photographic images, with minimal captioning, arrive last. Because the essays refer, constantly and without specific citational tags, to the images, the reader is compelled to flip back and forth — and is often frustrated by a certain productive misdirection in the path from text to image. But by this point the reader has already become split into multiple modalities of engagement.

Almost everyone will begin by flipping through the pictures, skimming the essays, perhaps reviewing the chronologies of better-known episodes (and dwelling on those less familiar).

The effect is double. On the one hand both the reader and the historical materials are fractured: the reader broken down into those different functions (looking, reading, relooking, rereading, skipping and skimming), the history parceled out analytically.

On the other hand, the book encourages higher-level syntheses at every turn. Repeating the movement from text to image (and back again), the reader weaves a fresh experience of both the pressure of events and personalities (sometimes overblown, as in the rather great-man account supplied here of the Mexican Revolution), and the structural causes and consequences of revolutions overall.

Contingency is the watchword, as in Enzo Traverso’s annotation of the German 1918: “All revolutions shake the totality of society powerfully: the old has disappeared, while the new has yet to take a clear form because it is still being constructed. Visions of the future diverge, conflicts grow, confrontations continue.” (210)

But of course the open-endedness of this passage’s language (“shake,” “disappeared,” “yet to take,” “still being,” “continue”) is itself dialectically expressive of a synthetic process (“totality of society,” “clear form,” “constructed”). The minuscule and the magisterial, the episode and the totality, flash together into historical focus — and then recede from view, only to reemerge elsewhere.

The effect is happily disorienting: blocking rote recognition while reanimating the total history within which this revolutionary sequence can be made meaningful for us. Another way to put this is to say, paradoxically, that Revolutions makes us meaningful for them: for comrades past (including the ones from whom we may wish to maintain some political distance).

Sacrifice and Loss

Insofar as the reader is activated by this material, the sacrifice and horrific loss registered in these images — the “body politic” of the people here is all too often the literal corpse: several heads of young men in China in 1911, murdered for cutting their braids; piles of bodies in Cádiz in 1933; seemingly endless executions in Germany in 1919; hanged bodies in Hungary in the same year — is reanimated within a new field of possibility and potential.

Yet this is a complicated process of identification, commitment, and historical imagination. It is particularly difficult in our period. As Traverso has argued eloquently elsewhere, the disastrous 20th century effected a major transformation of the archetypical figure of history: from comrade or partisan to victim.

Against this sea-change, and within the tradition Traverso names (following a thought of Benjamin’s) “left melancholy,” our defeated comrades constitute the vanquished. Such a tradition sees “tragedies and lost battles of the past as a burden and a debt, which are also a promise of redemption.”*

I would emend Traverso’s religious language to state, in a rather more ruthlessly materialist tone, that the dead cannot be redeemed (dead is, as Eric Hobsbawm once bitterly reminded an interviewer, dead), but the living can remake the world.

Isn’t that task of renovation in fact the very obligation of the revolutionary? Activation (or not) of the reader is, therefore, one measure of the book’s potential for success.

In this regard, the book’s enthusiasm for the revolutionary activity of the masses is elating; often the reader is swept into the streets, into the fleeting — and also patently distorted — bodily sensation of world-historical freedom. Again and again it is brief, vertiginous, extraordinary:

“It was,” we are told of the Hungarian Revolution of 1919, “a real revolution — that, for the first time, allowed poor children to know the delight of swimming in Lake Balaton — and it was a real war.” (170)

How are we to understand the relation between the miracle of the poor child at last swimming in the lake and the unfolding of a revolution? What kind of historical meaning can be made of the former which, far from a trivial delight, seems to be a certain fulcrum of human history in microcosm? And how does the revolution block, rather than enable, our available styles of representation, of giving form to history?

Can Revolution Be Represented?

“Revolution” is, in this regard, a dilemma rather than a political or historiographical concept, divided between the shock of embodiment and the demand for theoretical abstraction. On the one hand, the word expresses (or displaces) the flood of sheer experience, a collective shudder through which Marx’s “poetry of the future” is enacted, impossibly, in the insistent present.

In this aspect, “revolution” also names the fading or disappearance of the individuated person, and the animation of the collective subject. The Big Men loom over many of the chapters in Revolutions not because the book is in thrall to a retrograde vision of history, but because these men were avatars of collectivity, supplying a site of identification and collective self-representation.

One awful lesson of the period 1871-1989 is that the spectacular image of that avatar all too readily usurps the place of what had been its referent. A shorthand for this obscenity is “Stalin,” but saying so only falsely circumscribes the catastrophe. That, too, is a crucial inheritance for we who assume the burden and the debt of history.

If “revolution” thus careens us toward the body and its sensorium, it also, on the other hand, identifies phenomena that are the very opposite of “experience” in any of its aspects. What photograph can depict the seizure of means of production, or the expropriation of the expropriators? (After all, isn’t the impossibility and undesirability of such a thing what spurred Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky toward their greatest experiments in revolutionary abstraction?)

These are not discrete events any more than the proletariat is a mere conglomeration of individual workers, and they are neither depicted nor very much discussed in Revolutions. The poetry of the future will not be photographed; it is not an image, but a making, and this is why it is hard to represent and why the dialectic of text and image in Revolutions has to work so hard to sustain itself.

Needless to say, the seizure of the means of production is not photographed — but neither is the revolutionary swimming child. Thus the reader surfaces from their immersion in Revolutions with an intuition: that a preliminary task for today’s would-be revolutionaries, or for those of us concerned to actualize “revolution” afresh in our inhospitable situation, is to maintain the tension between experience and politics, to see the two poles as both preconditions for and solvents upon the struggle for freedom.

Deluded by the fiction of experience as the test of meaning, the revolution finds itself misrecognizing tear gas, police batons, ruthless reprisals, and year-zero manias as achievements rather than indices of weakness. Hallucinating on the strong medicine of proximity to state power, the revolution wheels into its opposite, and the barricade morphs into an abattoir.

The melodramatic quality of such oscillations is itself an artifact of the 20th century as it is given by this necessary and challenging book. Whether or not it can be made meaningful is up to us.

*Enzo Traverso, Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016, xv. In Traverso’s synthetic account, the political uptake of the Holocaust, the Gulag, and the memory of slavery displaced, respectively, the memories of antifascism, revolution, and anticolonialism (11 and passim). Traverso’s brand-new study, Revolution: An Intellectual History (London: Verso, 2021) promises a brilliant new synthesis.

November-December 2021, ATC 215