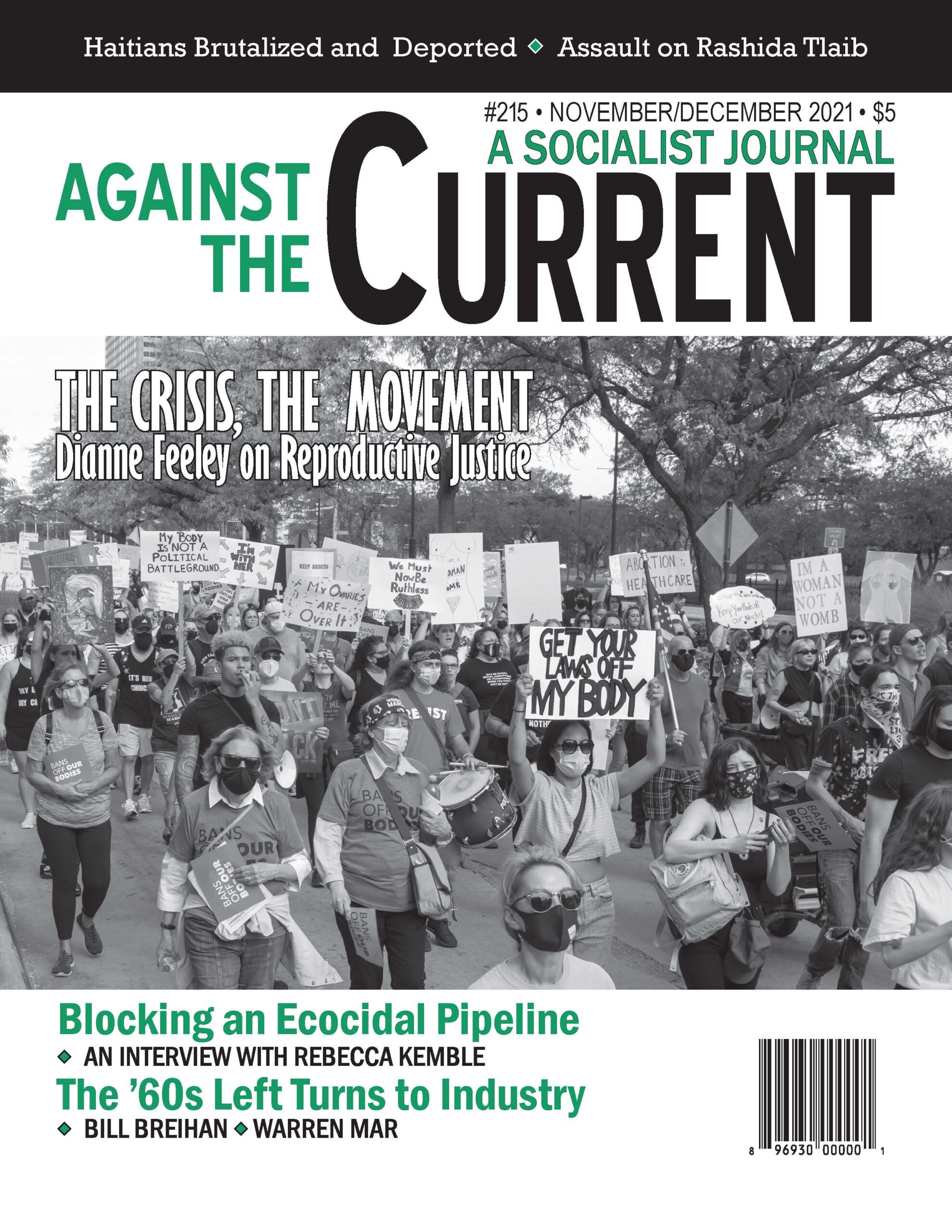

Against the Current, No. 215, November/December 2021

-

The Rising Price of Insanity

— The Editors -

Reproductive Justice on the Line

— Dianne Feeley -

Teenagers Are Children, Not "Bad Seed"

— an interview with Deborah LaBelle -

Blocking an Ecocidal Pipeline

— an interview with Rebecca Kemble -

The Ecosocialist Imperative

— Solidarity Ecosocialist Working Group - Hitting the Bricks for "Striketober"

-

The Assault on Rashida Tlaib

— David Finkel -

Nicaragua, as Elections Approach

— Margaret Randall -

Crime Scene at the U.S.-Mexico Border

— Malik Miah - Revolutionary Tradition

-

The '60s Left Turns to Industry

— The Editors -

The SWP's 1970s Turn to Industry

— Bill Breihan -

Organizing in HERE, 1979-1991

— Warren Mar - Reviews

-

Preserving Voices and Legacies: Jazz Oral Histories

— Cliff Conner -

On COVID's Death Toll

— David Finkel -

Reflections on Party Lines, Party Lives, American Tragedy

— Paula Rabinowitz -

Reclaiming the Narrative: Immigrant Workers and Precarity

— Leila Kawar -

Envisioning a World to Win

— Matthew Garrett -

Sharing and Surveilling

— Peter Solenberger -

A Labor Warrior Enabled

— Giselle Gerolami

Warren Mar

THIS ARTICLE WAS first written in preparation for an online forum hosted by the Labor Caucus of the Democratic Socialist of America (DSA). It has been edited for historical context and some background information on my involvement with the I Wor Kuen (IWK) and the League of Revolutionary Struggle (LRS), groups founded as part of the new socialist left during the late 1960s and ’70s.

Some background knowledge of the groups I was affiliated with is helpful to understand why we chose to go into particular workplaces and industries.

In new left stories from the 1960s and ’70s, the protagonist usually begins with their political awakening on a college campus. They then put their careers or graduate studies on pause, sometimes for a lifetime and entered a workplace to organize the working class because that is what their Marxist-Leninist political line encouraged if not mandated.

My story is a little different. Not in search of the movement, the movement lands on me: I was introduced to the new left and Marxism prior to my entrance into high school.

Born in 1953 and growing up in San Francisco’s Chinatown and North Beach, I became a regular in the pool halls. In one of these pool halls, Leway’s — short for legitimate ways — some of the regulars branched off and formed the Red Guard Party in 1967, one year after the Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, across the Bay.

They were allies of the Panthers, so Bobby Seale, David Hilliard and other Panthers would occasionally come by and hold court in the back of the pool hall as guests of the Red Guards. I got my first Red Book from an older sister’s boyfriend, who was in that circle.

I opposed the war in Vietnam, because they were killing Asians, and I liked Mao, mainly because white American politicians feared and hated him.

San Francisco was an epicenter of the antiwar movement and I was surrounded by it. I attended many demonstrations including the national mobilizations. On the west coast, these were held in San Francisco. In the ’60s San Francisco still had an active army base in our Presidio and Alameda Naval Air Station was seven miles away next to Oakland.

I fought with many of these soldiers on the streets and pool halls of Chinatown North Beach as they visited the strip joints on Broadway on leave. Before my conversion to socialism, I was a nationalist.

The Panthers and Red Guard also appealed to me because I hated the cops. Hanging out on the streets or in pool halls since junior high school, I was a regular target of police harassment. When I was 13, I was formally arrested for gang activity in a group fight. A member of the Red Guard found me and offered me and my friends legal representation in juvenile court.

This bound me to the Red Guards and Asian American new leftists, although I continued to avoid their recruitment efforts until I was well into my twenties. The Red Guard existed only a few years and their remnants would end up in I Wor Kuen (IWK, Righteous Harmonious Fist), westernized as “the Boxers.” The name was taken from the Boxer Rebellion in China, the peasant-led anti-imperialist movement that almost drove the first colonial powers from the mainland of China in the late 1800s.

The IWK was actually formed in NY Chinatown, with Asian students from East Coast Ivy League campuses and like the Red Guard in San Francisco, they first modeled themselves after the Panthers with a 12-point platform. They would move west in the early ’70s to begin work in the other of the two largest Chinese communities, NYC and SF, recruiting what remained of the Red Guard Party.

It was this group of IWK that I would formally work with in the early ’70s, culminating in my recruitment as a cadre in 1975. I would stay through the mergers when IWK became the League of Revolutionary Struggle (LRS), officially declaring ourselves Marxist-Leninist. I would remain, until our dissolution in 1990.

Imbedded in the Working Class, Prior To Marxism

I was 22 years old when I joined IWK and had already worked for many years both in union and non-union work. I had been a grocery clerk and member of UFCW, also a clerk at the phone company, CWA, and been in two Teamster Locals, warehousing and working in garages in San Francisco.

The first work place I met members of IWK was at the phone company. There was a national contract expiration in 1972 and a wildcat strike (non-authorized) in 1973. With other leftists, IWK was involved in that wildcat strike and worked with me, and I was able to learn more about the differing left groups involved at the phone company.

I also learned that part of fighting the company was fighting the union leadership involved in San Francisco at that time. The skilled trade white guys such as installers, linemen and splicers were the crafts that held most of the leadership in the SF Local 9410. The back-office service workers and operators, mostly women and people of color, were not involved and rarely attended meetings, much less held union office.

Although the wildcat strike was lost, CWA 9410 would change with the activism of the service workers. These workers would become the majority of the local and soon the leadership would change.

I was raised in a family of 10 children; my parents were immigrants from China and non-union garment workers. San Francisco was very segregated then. School integration did not even begin until I was in my senior year of high school, so I never went to a non-majority Chinese public school until I was in college.

My father came over at the height of the Chinese Exclusion laws in 1922 as a “paper son.” [Given the racist restrictions against the Chinese, those able to obtain papers indicating they were the children of U.S. citizens were able to immigrate. — ed.] San Francisco still barred Chinese from public schools and the public hospital, but it was okay for him to work 12 hours a day in a factory and that’s what he did.

He would remain in that line of work throughout my childhood and well after I left home. He worked in a garment factory until he was 83. My mother joined him in that line of work when he was allowed to bring over a war bride.

For Chinese-American men who served during WWII, in lieu of other GI benefits, this was an important privilege. Anti-miscegenation laws were still in effect in California when my mother arrived in 1946.

If there was ever a major manufacturing industry in San Francisco, garment would have had to rank as one of the top two with food processing being the other. It was one of the few industries that hired Chinese, for both union and non-union work. Chinese women along with the growing Latina immigrants would remain the majority of the garment workers in San Francisco until the industry’s ultimate demise in the 1980s.

I explain my background: going into the working class or even getting a working-class job was not a choice, although IWK pushed me into HERE (hotel and restaurant employees’ union). I worked because I had to, as did my parents and all my siblings.

That we found the best jobs possible and often unionized jobs, was by chance and struggle. First, we found out that union jobs paid better and we had to get into industries and unions that would not block our entrance.

Even in liberal San Francisco, most skilled trades and even the better public sector unions were still excluding Chinese and other people of color in the ’60s and ’70s.

Marxist Path into the Proletariat

IWK did not declare itself Marxist-Leninist until the mid-’70s, just a couple of years before our transformation into the League of Revolutionary Struggle (LRS), with our merger with the August Twenty Ninth Movement (ATM), with roots in the Chicano/Latinx movement and the Congress of African People (CAP), led by revolutionary nationalist poet Amiri Baraka, who also gravitated towards Marxism.

In short, our formation started with a majority of cadres being people of color. Even when white recruits swelled our ranks, we remained a heavily people of color organization, dominated by women of color in our leadership.

This is important because it not only limited our entrance into the industrial working class, especially the skilled trades, but also informed our political decisions of what part of the working class it was important to organize.

ATM, CAP and IWK also were rooted in our own communities of color. All of us did work beyond the college campuses in our own communities: CAP in the ghettos of St. Louis, New Jersey, NYC and Detroit; ATM which formed in Los Angeles, moved north to San Jose, Oakland and east to Colorado.

IWK, which started in the New York and San Francisco Chinatowns, became Pan-Asian and moved to most communities on the west coast from Los Angeles to Seattle, Washington and some of our cadre moved back to the Hawaiian Islands. It was in some of these cities in the Northeast where IWK and CAP first did work on issues such as police brutality, school desegregation and equal electoral representation.

Likewise, IWK and ATM met in Oakland, San Jose and Los Angeles on issues such as U.S. intervention in Central and South America, police violence, housing rights, immigrant rights and a host of other issues. In short, our community issues were never separated from working class issues and we never relied on an industrial concentration as a sole or even main place to organize workers.

Ironically, the same issues I listed above are as relevant today as they were forty years ago and still resound with divisions between the white working class and workers of color.

We also had to be realistic about where we could have an impact, where we could land a job, and whether a small group of left-leaning people of color could impact a largely white, male-dominated union, industry or work force.

I am proud to say even today that we never gravitated totally to the industrial proletariat, especially in manufacturing. We went where our people worked: in the service sector, hotels, restaurants, back office typing pools (before computers), hospitals, delivery and other types of drivers, public transport, communication (phone companies), warehousing.

In the public sector we worked in a lot of hospitals and schools because they not only were union jobs beyond the control of union apprenticeships that barred our entrance, but also because they served our underserved communities of color so that organizing better conditions at work often meant better outcomes for our communities.

This was also true of public transport, which in the ’70s became one of the better jobs for men of color.

Once I became political, there was no turning back. We were attacked by the Chinese Nationalists (KMT) in street battles because we were pro-China. The FBI has called and even went to my mother’s house after I was long gone.

The hotels that hired me knew I was not only an open commie, but we sold our paper in back of the employee entrances, as I did on the streets of Chinatown. Even with the various mergers, I always remained an open member. This meant that I was always redbaited, and for a time blacklisted from San Francisco hotels. But I got back in.

Brief History of Local 2

The Hotel and Restaurant Union, Local 2, by the early ’70s became the largest private sector union in San Francisco. Even with the demise of unionization generally and the loss of union restaurants in San Francisco, Local 2 holds this place today, mainly through the growth in hotel jobs, the expansion of the city convention center and the building of new sport stadiums and their representation of food service at the expanding SF International Airport.

In the 1960s and before, HERE was not one union but five. There were two craft unions, Cooks and Bartenders; two server unions, waiters and waitresses; and a miscellaneous union.

Food servers were separated by gender in those pre-affirmative action days, with men only in the first-class fine dining dinner establishments and women relegated to the lunch counters and diners. Having two separate unions codified this sexual discrimination.

The miscellaneous union — dishwashers, bellhops, porters, room attendants etc. was majority people of color. In San Francisco, African Americans held these jobs during the great migration; by the 1960s it was predominantly Chinese, Philipino and Latino.

Even in the 1980s it was not uncommon for the class A houses to hire men only as servers. I worked in an Italian restaurant where all the waiters were white men. The only Black person in the restaurant was the hat check “girl,” a middle-aged African American woman.

Most of the cooks on the line, including myself, were Chinese. Only the Chef and Sous Chef were white. The dishwashers were Latino. This was not an uncommon racial workplace distribution of labor for many of the places I worked during my decade as a cook in San Francisco.

With the merger of the five unions into one industrial union in 1975, making up HERE Local 2, we became the largest private sector union in San Francisco and a minority-majority and female-majority union. However, the union officers and staff, many of whom came from the old craft unions of cooks, waiters and bartenders, did not reflect the membership.

This would remain a source of tension with the members, and it was in this period when I became a member, activist and eventually one of the few elected Chinese officers of Local 2 and also a delegate to the SF Labor Council. This was part of our strategy in the LRS, not only to improve the industry and workplaces for minority workers but also to change the unions by empowering the members within those unions, especially women and people of color.

My Entrance into Local 2

I hated restaurant work. I washed dishes and made salads at a small place downtown when I was in high school. I swore I would never do it again after I got other jobs mostly in warehouses or garages. I hated interacting with customers, mostly I hated serving white people.

To this day, one of the reasons the service sector has become predominantly immigrant is because subservience is almost a job requirement, although it is now couched in terms such as “social skills,” by human resource wonks. Restaurant and hospitality customers were condescending and racist, which is why I always gravitated toward garage work or warehouse work.

This is the same reason I became a cook rather than trying to ingratiate my way into becoming a waiter or bartender, which in this industry, with gratuities, were much better paid positions.

But in 1975 I was already a cadre in IWK, which became LRS in 1978. The LRS had one of the most radical positions on the “national question,” which was the reason I had joined IWK. Our concentration in jobs was determined not only by our own politics but came out of how the capitalist system was organized in the United States.

The foundational racism woven into many unions still haunts white workers in this country by limiting their ability to organize. The LRS always had more people in service rather than production, because those were the industries that first allowed people of color and women in.

The reason IWK/LRS was so insistent and needed me in Local 2 is the same reason I was an asset to them in Chinatown. I’m fairly fluent in spoken Cantonese, the predominant dialect for most Chinese immigrants on the West Coast, especially San Francisco.

IWK had some cadres already working in Local 2, but they were not making much headway, especially among Chinese immigrant workers. Most of their cadre at that time had not grown up in Chinatown, nor been forced to attend Chinese school by immigrant parents.

As a result, many Chinese American radicals were not bilingual. This precluded them from effective organizing of immigrant workers, especially in lower-level jobs. This was the majority workforce in HERE.

By 1979 I was a seasoned and good cadre, so as much as I fought it, I gave up my Teamster job and went into Local 2. Even with a union, I always made less money and had lower benefits in HERE than I would have had I remained a Teamster at UPS.

Another Chinese American cadre (who was not bilingual) was already working at the Holiday Inn as a waiter. He was competent and well-liked by the managers and upon his recommendation I was given a job as a busboy. Just as I suspected, I hated it.

Due to my fluent English, I was in line to be promoted to waiter in short order, but this never happened. Finally, after over half a year as a busboy, my white female supervisor sat me down for a cup of coffee and told me why. She said I needed a better “attitude.”

She told me I was a hard worker but needed to be friendlier. I didn’t smile enough. She was trying to help me. I wanted to kill her, right there, in the dining room in front of witnesses and all. I needed to get out of there and started looking.

I spent about a total of nine months as a busser in Local 2. I even thought about trying to transfer into the hotel storeroom, which is the receiving department inside most big places. My long experience as a shipping clerk and warehouseman would have easily qualified me. The problem is they were not in a social working environment. Very few of these jobs existed, in hotels and they rarely interacted with other workers, not a good place to be when organizing.

Read Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential

But I found one group of workers who were, if not respected, feared by everyone: cooks. They could swear, they could yell, they had skills many managers did not and if they were good, they were indispensable. So I left the Holiday Inn, enrolled in a quick six-month course at the SF Community College which got me back into Local 2, HERE as a line cook at a union restaurant down by Fisherman’s Wharf.

The goal was to always get into a hotel because that is where the organizing power of the union was. The goal of the LRS was to change the union leadership and get ourselves and progressive allies elected into union office, which I would eventually do. We also changed that leadership and eventually the staff to reflect the makeup of the membership, majority Asian-Pacific Islanders and Latino.

The line of the LRS at that time was that we would not take any staff or appointed positions. All union positions we held had to be elected from our position in the rank and file.

We would change this position in the late ’80s. But at the time of my entrance into HERE, Local 2 we only sent cadre into rank-and-file jobs as workers, never directly into staff positions. We believed then that we should only occupy positions within the union that our fellow workers elected us to.

I was quickly promoted in that restaurant and served as the chef there until I entered the union’s apprenticeship program. This is something that no longer exists today. Chefs in restaurants could be union members, even as supervisors.

In many ways I was over-qualified to be an apprentice, but the apprenticeship gave me two advantages besides a higher formal paper certificate. It got me entry into one of the largest hotels in San Francisco — in one of the largest chains in the country. We said that working for the Hyatt was like working at General Motors.

In the early ’80s when I cooked at the Hyatt on Union Square, now called the Grand Hyatt, they had over 500 workers, three restaurants, banquet facilities for 700. The kitchens had over 50 cooks, the majority were Chinese, followed by Philipinos and Latinos.

I fit right in. I took my training seriously and the apprenticeship put me back at SF City College night courses for culinary. With my experience in a good restaurant, I became one of the better cooks at the Hyatt, gaining respect from co-workers and also begrudging respect from management.

Because of my native-born English abilities, I was able to buy cookbooks and read them on the side, I subscribed to Gourmet and other in vogue culinary magazines. I was also not unaware of the privileges I had in education. I once shared all my notes with a Salvadoran immigrant who was the apprentice behind me, because his note taking abilities in English did not help him keep up at the SF City College night classes.

This was another example I tried to set with my organizing. I shared my knowledge with the Latinos and Philipino cooks even if they were not working in my station. Once a Chinese cook asked me why I was showing a Latino dishwasher how I was making a sauce. The dishwasher asked me, “What I was making?,” and I showed him.

Many Chinese cooks who had to learn from memory did not want to share with other nationalities their craft, just as the older European cooks tried to keep Chinese from moving up in the kitchen hierarchy.

Within a year at the Hyatt I was elected shop steward, and being bilingual also helped me to cross departments where other Chinese immigrants worked, especially housekeeping and stewarding. Violations of the union contract were more prevalent among the unskilled, immigrant departments. I also tried to promote interdepartmental and craft solidarity which at that time was not easy due to the historical divisions in the industry and union.

I headed this section with “Read Kitchen Confidential” because if any leftist is thinking about getting into cooking and hasn’t really worked in a shit industry or had a long list of backbreaking, physically draining jobs, read Kitchen Confidential to see what the work environment is really like.

The reason many cooks of all nationalities love Anthony Bourdain’s portrayal of our work is because he came out with the first, if not only, honest rendition of what it was like to work in a first-class professional kitchen and survive. He also finally gave due credit to why every professional kitchen I ever worked in was mainly staffed by men and women of color, regardless of cuisine.

It was not just the sex, drugs and booze although there was plenty of that, but the grueling pace of the work which is why we hold industry power. It is why when cooks walk out, a restaurant closes. It was why I was able to tell an owner to go fxxk himself, and he offered me a promotion.

I always could work because hiring in restaurants was held by chefs, not a corporate HR dept. Back then there were no resumes or even a job interview. You showed up at the back door, talked to the chef and came equipped with your knives, and asked for work. You worked a shift (that was the interview). You made it or not, some didn’t even finish the shift.

I was also one of the best and fastest cooks and could work any station, help any cook who was behind or in trouble and set an example of this on the line. I could also really screw my managers, if I was unhappy, and they knew I could do things faster, and often better than they.

I learned this from other Chinese immigrant workers who said to me, “Warren, what we lack with our mouths, we must make up for with our hands.” I learned to have both. Like Bourdain, my time on the lines in the hotels and kitchens in San Francisco has given me more scars than in any other jobs I’ve ever held, and I cut my teeth in construction warehouses, and garages as a Teamster.

Getting Elected, Going on Staff

The LRS had run for union office before but we had lost. Just prior to my entrance, Local 2 was actually under international trusteeship, because a reform slate had won office the year before.

When I was a shop steward at the Hyatt, the President of the local was actually a member of the old reform slate who split off, so the International in lifting the trusteeship allowed ex-Vice-president Charles Lamb to become the president. All the other members of his slate were excluded from office because they never renounced their opposition to the International or the trusteeship.

He would swear me in as shop steward with the support of my co-workers, then remove me when management complained about my filing too many grievances at the Hyatt.

I would be on a slate to run against him in 1982, which we won, removing him from HERE Local 2.

Ours was a coalition slate. The LRS was preparing a slate under our own leadership with a Latino member running for President and myself running for vice-president. But the problem was that Local 2 always had a lot of leftists and for that election we actually had five slates, three of which could be called progressive or reform slates under various left leadership.

Given the existing conditions, all the reform and left slates could have lost, and the incumbent slate would have probably won. Under this scenario, there was a lot of jockeying for slates to merge.

No slate wanted to give up the presidential seat except us. We finally did so, with our Latino candidate dropping back to the vice-presidential slot and I dropped back to an elected position as a rank and file member on the executive board, which meant that I remained cooking even after the election.

There are practical reasons why most left groups or even reform groups did not want to give up the presidential candidacy. Under the HERE constitution, all power resides with the president. All staff, hiring, staff assignments and even shop stewards such as myself who were elected could be removed by the president.

Past practice has also given the President total control over the bargaining of contracts. Elected rank and file bargaining committees can serve as little more than a rubber stamp if the president is so inclined.

Before our tenure, it was not uncommon for the President of Local 2 to sit down with an employer, sign a contract or extend one without so much as a notification announcement to the affected workers on what was being signed and for how long. Translation was nonexistent.

So, why was the LRS willing to give up the presidency with this concentration of power which exists to the present day? Local 2, as with all of the U.S. labor movement, had another problem looming. We were not organizing new workers and in fact unions no longer knew how to do it.

One of our major policies or required points of unity with the other slates was that they must put new organizing as a priority. Only one slate was willing to make this commitment to us, and that is the one we merged with.

Sherri Chiesa, who served as Secretary Treasurer (in HERE mainly an administrative job) under Charles Lamb, in unity with a group of young organizers, many whom were Alinsky-trained formerly of the United Farm Worker (UFW) campaigns, decided to break with Lamb. [Saul Alinsky was the author of a staff-driven method of community organizing — ed.]

They felt the union had to pivot into organizing new hotels rather than focusing on protecting what we already had. We agreed.

Without the Left, including the LRS, in Local 2, I do not believe that the union would have changed as much as it has nor as rapidly, especially in the area of minority representation among the rank and file and on the union staff. Our success in organizing also forced the discussion nationally and many HERE locals without Left influence have changed, because the International Union today has changed.

However, this doesn’t mean there aren’t challenges. HERE is under a similar Alinskyist-style leadership represented by Sherri Chiesa. Because HERE as a whole is still staff driven, the Alinsky model has favored the hiring of educated outsiders, college-educated middle-class workers who themselves never had to work in the industry and cannot really understand what the workers face or why they hate their jobs.

In a union, I fear this connot but have a detrimental effect. This goes way beyond wages and working conditions. In the service sector, where immigrant workers are concentrated, it is the daily, hourly erosion of human dignity, usually operating through sexism and racism.

Revived Organizing

In 1982 the writing was on the wall, because we were in the midst of a one-year strike against most of the restaurants in San Francisco, a strike we were losing and would continue to lose after our election.

Under the old regimes, because of history and San Francisco having a liberal patina, many leaders including Charles Lamb thought they could bargain their way out of a fight. But in 1981 after Reagan’s firing the air-traffic controllers, the restaurants were not in a bargaining mood. They wanted decertification and their argument was that we had not organized the new non-union restaurants, therefore why should they stay union?

In a twisted way they were right. The hotel contract was set to expire in 1983, so the 1982 union election would determine how we would deal with that same issue. The one advantage in the hotels was that we still held on to the critical mass of hotels. Only a few large ones had opened non-union, but we had not started any organizing drives.

Our position was that we could not allow the non-union sector to grow like the restaurants. We had to go after the non-union hotels. On this basis, we gave up the presidential seat for Sherri Chiesa and our slate won: all of the top three executive offices, and nine out of 10 rank-and-file executive office positions.

Under her leadership not only the elected officers but the staff composition changed. We hired more bilingual staff and people of color. Local 2 also hired gay representatives, reflecting that part of our membership.

More important, the staff culture slowly changed to be more organizing focused. Business Agent titles were changed to Union Representative. We expected more from staff. Turning out or activating members became a bigger part of the job, not grievance handling.

We formed workers’ committees in each hotel, sometimes in various departments to replace the old shop steward system. We made the workers in the union hotels fight their own grievances collectively.

Meetings were translated into at least three languages. In larger meetings they could be simultaneous with workers wearing earphones so a meeting could be shorter. For important meetings, especially on organizing drives, we would hold them at different times of the day so various shifts would not have to come to a meeting during their sleep times or miss a meeting because they worked a swing or night shift.

Eventually I would join the organizing department and work full time in Local 2 on the first organizing drive in one of the largest new non-union hotels. It took over three years, but we won that organizing drive. As with the LRS, Local 2 needed a Cantonese-speaking organizer. We won that hotel after a bitter three-year fight of underground organizing, hundreds of demonstrations, civil disobedience, arrests, and a boycott.

This organizing drive would serve as a model and an example telling other hotels in San Francisco that Local 2 would do whatever it takes to organize and win. The 1983 hotel contract was also signed without a strike because the employers knew what we would do: no more walking in a circle picketing.

Our picket lines became mass demonstrations. We occupied hotel lobbies, we blocked cable cars in front of hotels, causing traffic jams. We took arrests. We demonstrated at the opening night of the SF symphony because the owner of the hotel we were organizing was on the board. We hounded owners at their mansions in the suburbs, posting wanted posters for them in front of their neighbors.

Epilogue

While I will always look askance at college graduates as staff organizers, I became one. I went back to college after leaving Local 2 and graduated when I was over 40, after years of organizing on shop floors.

I went on to get a Master’s degree and when some of my high school friends seemed surprised, I told them, if you can read Marx, Lenin and Mao you can read anything.

November-December 2021, ATC 215

It would be great if you could elaborate on that brief paragraph toward the end, “We formed workers’ committees in each hotel, sometimes in various departments to replace the old shop steward system. We made the workers in the union hotels fight their own grievances collectively.”

How were those workers’ committees initially organized, and how were they able to operate “collectively” day-to-day?