Against the Current No. 213, July/August 2021

-

Infrastructure: Who Needs It?

— The Editors -

Burma: The War vs. the People

— Suzi Weissman interviews Carlos Sardiña Galache -

Afghanistan's Tragedy

— Valentine M. Moghadam -

The Detroit Left & Social Unionism in the 1930s

— Steve Babson - On the Left and Labor’s Upsurge: A Few Readings from ATC

-

Detroit: Austerity and Politics, Part 2

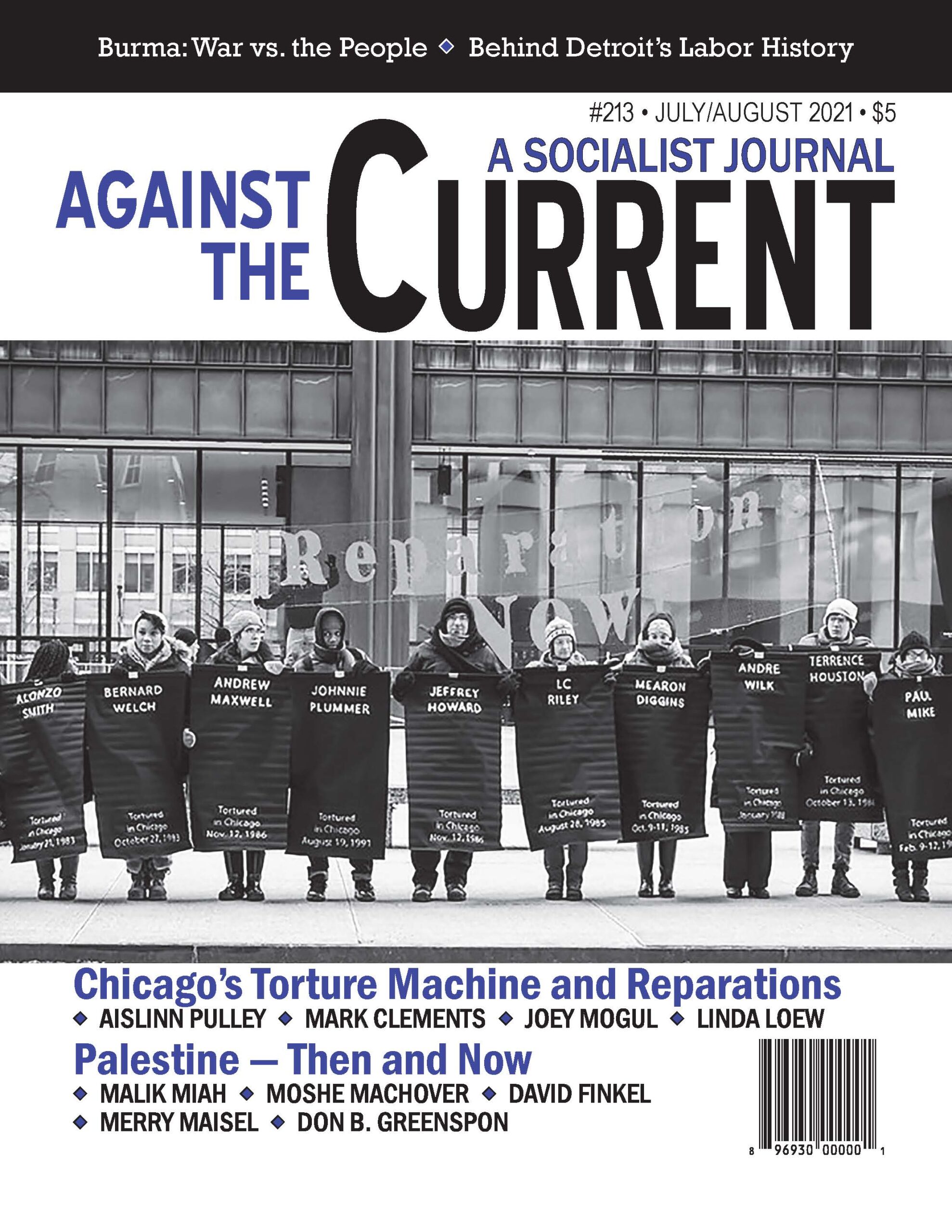

— Peter Blackmer - Chicago's Torture Machine

-

Reparations for Police Torture

— interview with Aislinn Pulley - Diana Ortiz ¡presente!

-

A Torture Survivor Speaks

— interview with Mark Clements -

Torture, Reparations & Healing

— interview with Joey Mogul -

The Windy City Torture Underground

— Linda Loew - Palestine -- Then and Now

-

Palestinian Americans Take the Lead

— Malik Miah -

Zionist Colonization and Its Victim

— Moshé Machover -

Conceiving Decolonization

— David Finkel -

Not a Cause for Palestinians Only

— Merry Maisel -

When Liberals Fail on Palestine

— Donald B. Greenspon - Reviews

-

Immigration: What's at Stake?

— Guy Miller -

Exploring PTSD Politics

— Norm Diamond -

A Life of Struggle: Grace Carlson

— Dianne Feeley -

Living in the Moment

— Martin Oppenheimer

interview with Joey Mogul

JOEY MOGUL, A partner at the People’s Law Office and a longtime activist in the struggle around the Chicago Police torture machine, drafted the Reparations Ordinance. Mogul was interviewed on May 13, 2021 by Linda Loew and Dianne Feeley on the movement and its impact on survivors’ attempts to heal.

Linda Loew: We want to step back just a little bit in time and ask about your experience giving testimony on Chicago torture cases to the United Nations Convention Against Torture. What impact did the international attention have on the exposure of torture in Chicago? How did this contribute to the idea of reparations?

Joey Mogul: It was Standish Willis, a member of the National Conference of Black Lawyers and a founder of Black People Against Police Torture, who came up with the idea that we needed to bring the Burge torture cases to international fora. He was following a long tradition of Black radical activists in thinking that we needed to take this racist state violence to the international human rights community. This is in the tradition of the We Charge Genocide petition by William Patterson and others to the United Nations in 1951.

Stan, unfortunately, was unable to go because he had to argue a case in the Seventh Circuit Court. I found out that I was going to be traveling to Geneva, Switzerland, to present this testimony to the UN Committee Against Torture less than 24 hours beforehand. Sponsored by the Midwest Coalition for Human Rights, I had eight hours on the flight to figure out how I was going to boil down 20-plus years of work into a three-minute presentation to the UN Committee Against Torture.

This occurred in 2006, after the Bush administration had invaded Iraq. In addition to misrepresenting the “fact” that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, Bush declared that one of the reasons for the war was that Saddam Hussein was torturing civilians. But we know that during the so-called war on terror, and particularly during the Iraq war, U.S. military officials were torturing Iraqi civilians. This was happening both at Guantanamo and black sites around the world.

The U.S. government came to the UN Committee Against Torture to defend the government’s record about complying with the Convention Against Torture. Essentially its argument was “yes, given 9/11, we’ve made some mistakes in the war on terror, but domestically the United States is a beacon of human rights.”

Impact of UN Report

When the UN Committee Against Torture heard my presentation on the Burge torture cases, they were very anxious to learn more about what was going on domestically. I had the opportunity to work with Andrea Ritchie who had drafted a report, In the Shadows of the War on Terror: Persistent Police Brutality and Abuse of People of Color in the United States. We were the ones discussing U.S. racist police violence, with the Burge torture cases example A.

After reviewing our evidence and the testimony I provided, the committee issued findings noting the limited investigation and lack of prosecution in the Burge torture cases and calling on the U.S. government to bring the perpetrators to justice.

The committee also found that the U.S. government did not comply with the Convention Against Torture around Guantanamo Bay, that there was torture at Abu Ghraib in Iraq. This was significant because there’s been a long history where our government is willing to acknowledge that torture occurs outside the country but when we see acts of torture that are racially motivated, particularly affecting Black and brown people inside the United States, it isn’t called torture but “abuse allegations.”

When the findings came out on May 19, 2006 I was back in Chicago and we were having a court hearing that day about whether the special prosecutors’ report would be released. This was the result of a campaign that I helped found called the Campaign to Prosecute Police Torture.

We had gone into court demanding that special prosecutors be appointed to investigate the crimes of torture committed by Burge and his henchmen — not just the crimes of torture, understanding that the statute of limitations had expired, but also investigate perjury and obstruction of justice. This wasn’t just a litigation strategy.

We held rallies and events to support this Campaign to Prosecute Police Torture. We went to Gospel Fest and circulated petitions, submitting over 2000 signatures.

As the UN findings were released, the special prosecutors had just finished their four-year investigation, which cost seven million dollars. We expected them to release the report and then say, “Too bad, so sad. Yes, torture occurred, but we can’t do anything about it. It’s time to close the book on this.”

The press was all there but the report wasn’t released that day, so they had nothing else to report on but the committee’s findings. It was monumental to have an international human rights body, one of the highest human rights bodies in the world, draw this conclusion

.

It also had a profound and healing effect on the torture survivors because not only had they been tortured and incarcerated based on coerced confessions, but they had gone into court and told their lawyers, the prosecutors, and the judges that they were tortured. Time and time again, they were disbelieved, discarded and dehumanized. I can tell you as a movement it stirred us on. It propelled us to fight on.

By learning about international human rights and specifically the Convention Against Torture, we also read General Comment Three, where they talked about how you redress these egregious human rights violations and discussed the essential elements of reparations.

One is that there must be financial compensation, but they also talked about the need for restitution, the need for rehabilitation, the need for satisfaction from being found to be telling the truth. There is also a commitment not to repeat the violation. For me, that was quite an education about the essential elements of reparations.

Of course, I’m also grateful for all the work of so many Black radical organizers and activists in the United States who have been fighting for reparations for people of African descent for over a century. I learned from N’COBRA (National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America) that reparations are always more than an apology and a paycheck, but it was helpful to have those elements spelled out in the UN Committee Against Torture’s legal doctrine. That’s what helped inform me when I was drafting the reparations ordinance.

Dianne Feeley: It sounds like there were many organizations that were working to expose the torture cases. You have already mentioned the National Conference of Black Lawyers and Black People Against Police Torture. And of course, you wear two hats, as an activist as well as a lawyer. Tell us a bit about the early days of this struggle.

JM: There has been a lot of organizing and sometimes a breakthrough we didn’t expect. Back-in-the-day I was part of Queer to the Left. Around 2001 or 2002 we teamed up with Gay Liberation Network to drive Dick Devine, then Cook County State’s Attorney and longtime Daley operative, from the gay pride parade.

While the network was angry that Devine wasn’t prosecuting cops who harmed gay people, we raised the issue of the Burge torture cases. We organized an entire contingent and jumped in front of his contingent with our sign, “This Dick is not so divine.”

Although he’d been a regular in the annual gay parades, he never came back. I always think whether you’re in a queer group or not, it’s always women and queers who are really the backbone of the organizing efforts. We’re the ones calling the meetings, we’re the ones facilitating, we’re the ones making and passing out flyers…. It’s just the truth. Yet it’s often the women and queer people who get erased from the struggle.

Certainly, if we look at this long organizing campaign, it was driven by the torture survivors and their family members. It was mothers who were out there from the beginning.

The guys on death row organized themselves. They called themselves The Death Row 10. Then they reached out to their mothers and family members and said, “go connect with others on the outside for us.” The mothers became the spokespeople for their children; they were the organizers out on the street. They brought people together and insisted “You need to care about my child.”

JoAnn Patterson, Louva Bell, Castella Cannon. Now, we have Armanda Shackelford, whom you probably met when Gerald Reed was recently released. Jeanette Plummer, whose son Johnny Plummer I represent, used to come to all these events. She’s now physically unable to attend, but the mothers are always the ones who show up, who keep struggling.

DF: Could you speak about the trauma of so many of those who were tortured at such a young age — 13 years old, 16 years old? The violation of their bodies and their minds, and the trauma paradigm so early in life is horrendous.

JM: We’re dealing with anti-Black archetypes, particularly of Black youth. Mark Clements was 16, and that was in the early ’80s. You’re talking about Marcus Wiggins and Damoni Clemon and Diyez Owens and Clinton Welton, all of whom were brought into Area 3 and tortured.

My client Johnny Plummer was tortured at Area 3 when he was 15 years old. The language about the so-called super predator, Black youth wilding and other racist tropes led to the passage of the Violent Crime Act of 1994. We see this demonization of Black youth, of an entire generation. We see this impact in the way the torture was being used.

LL: Except for investigative reporter John Conroy’s “House of Screams” 1990 feature in the Chicago Reader it seems the international spotlight is what generated more coverage and attention.

JM: It’s true that once we got these findings from the UN Committee Against Torture in May of 2006, the movement got bigger. By October 2008 Burge was finally indicted for perjury and obstruction of justice.

It wasn’t just the local U.S. attorneys who were involved in that case, it was also the U.S. Department of Justice. U.S. officials in Geneva were having to answer about these torture cases. I do think that made a difference.

Now was the prosecution of Burge enough? No. Did it meet the material needs of the torture survivors? No. Did it serve to rectify all the harm and devastation wrought on the torture survivors, their family members, and affected Black communities? Absolutely not.

I think we’re living through a time where we can see that prosecution of police officers is not enough. It’s feeding a criminal legal system that we’re trying to dismantle.

Dehumanization Continued

One aspect of the court is that the torture survivors don’t have the ability to speak and in the way they need to tell their truths. Court is so limiting. You get asked a direct question. You can only answer that question.

You get cross-examined and to be honest, during Burge’s trial, it was not a healing for Anthony Holmes, Mark Clements, Gregory Banks, and Melvin Jones to have to relive their torture experiences and then be cross-examined with this anti-Black racism about what gangs they belonged to or what criminal activity they were involved in.

It was just part of the dehumanization they had experienced. When Anthony Holmes testified against Burge, he looked him in the eye and shared the pain and the trauma he experienced. Anthony walked out of that room and went to a side room where he broke down and cried for 45 minutes.

That’s when I recognized that this criminal proceeding was just re-traumatizing him. This is what INCITE! Women, Gender Non-Conforming, and Transpeople of Color Against Violence tells us. Just as with rape survivors, it’s not healing to go through a criminal prosecution. It’s not providing survivors with any of the tools they need to cope and live on. That’s why we needed reparations.

I’ll continue to be a lawyer, but I understand it’s the organizing that creates the container that, in Mariame Kaba’s words, allows us to all come in and fight alongside one another. It’s how we are horizontal in our work together.

When we are doing this organizing work, the torture survivors are with us side by side. In fact, they’re the ones whom we center. They’re the voices we need to hear. At every single reparations event, we ensure that torture survivors are front and center.

In the reparations campaign, the questions were: “What do you want in a reparations campaign? What do you want in the legislation? What do you want to tell people?”

Often when we ask people directly affected by police or state violence, we ask them, “Tell us what happened to you?” The question forces them to relive their trauma. Instead, we need to ask them: “What should be done? What are your hopes and dreams? What can provide you with healing and nourishment?”

I saw the futility in some of what Burge’s prosecution and conviction meant. That’s why we went on to push for reparations, which I believe was an abolitionist struggle.

LL: How did the reparations ordinance come about?

JM: Stan Willis and Black People Against Police Torture were the ones who originally put out the call for reparations. For years we had talked about how many of the torture survivors never had access to financial compensation because the torture had occurred decades ago. Many of them were incarcerated and unable to sue. The statute of limitations expired years ago.

Black People Against Police Torture wanted there to be a Chicago Torture Justice Center. In the United States, there are 20 or so psychological counseling centers that receive federal funds to provide mental health services to people who’ve been tortured. However, the U.S. government only provides funding to those who’ve been tortured outside the United States.

We have one of those torture victims centers, called the Kovler Center; we had been working with and in solidarity with them. Black People Against Police Torture saw that as a model for the Burge torture survivors and family members.

After Burge was convicted, I felt the conviction was not meeting the material needs of the torture survivors. It wasn’t providing them access to mental health services. It didn’t provide them financial compensation. It didn’t challenge the dominant narrative. I helped co-found Chicago Torture Justice Memorials.

We convened a group of artists, educators, torture survivors, family members, activists. We put out an open call and invited everyone under the sun to submit a speculative memorial. How would they memorialize the Burge torture cases?

We wanted not only reckoning with the heinous racist violence that these cases involved, but to do justice to the perseverance and resilience of the torture survivors and their family members.

We promised everyone that all submissions would be in the exhibit. In October of 2012, we had an exhibit of over 70 submissions at the Sullivan Galleries, which is part of The Art Institute of Chicago.

In addition to sculpture, photographs and audio, we had people submit how they would teach the torture cases in their sociology class or international human rights class. An art teacher from Bowen High School — which Burge attended, now an all-Black high school in an all-Black neighborhood — invited his students to imagine how they would memorialize those cases. As part of the speculative memorial, I drafted a reparations ordinance. Never in my wildest dreams did I think we were going to file this.

It was amazing to have the torture survivors walk through the galleries and see their lives reflected on the walls. I’ll never forget Anthony Holmes, one of the first survivors tortured by Burge, talking about how amazing it was that in this gallery, with its pristine white walls of art, was his life in the gray, dingy, dark, dirty cells of Pontiac and Illinois Department of Corrections.

We invited people to reflect on the work. What would a public memorial look like? That then led CTJM to take a deep dive into what other public memorials look like in the United States as well as around the world. We looked at memorials in Chile, in Argentina, in Germany and South Africa.

What Reparations Look Like

I also started to look at the reparations legislation from Chile, Argentina and from Kenya with the Mau Mau people. We also met with Juan Mendez, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture. He came to Chicago to meet with torture survivors. He talked about his experiences when he was tortured in Argentina’s Dirty War and the work they were doing to seek redress.

We held another exhibit, “What do Reparations Look Like?” I had been very much moved by people’s contributions and comments at the first art exhibit and in getting the torture survivors’ input and experiences. Many people focused on the need to educate people about the Burge torture cases.

I knew that when the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 passed, part of the redressing how Japanese Americans were rounded up and put in concentration camps during World War II included $5 million to educate about that injustice.

What demand could we put on the city of Chicago to educate about the torture cases? The city controls the public schools, including the city colleges. These colleges should be free for the torture survivors and their family members, including grandchildren. Youth and particularly family members can have a curriculum that teaches their history and recognizes the generational trauma that has occurred from this long legacy of violence. We now have a curriculum that was crafted by teachers in the Chicago Teachers Union, torture survivors and others.

We mounted a grassroots campaign for the reparations ordinance. It was a multi-racial, multi-generational effort of many organizations including the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, We Charge Genocide and the work of Mariame Kaba, and Project NIA.

Mariame Kaba is the all-time best organizer. She is the Beyonce of social justice — and made sure there was a youth of color delegation to the UN Committee Against Torture in 2014. We then also teamed up with Amnesty International USA.

We mounted a campaign in 2014 and 2015 during the first tidal wave of the Black Lives Matter movement. It was also in the midst of heated mayoral and aldermanic elections, where we demanded the reparations legislation get passed.

We did something every week. We had rallies, we had demonstrations. During winter, We Charge Genocide took over the transit system and went on trains to organize. We had Twitter power hours.

We held teach-ins on the Burge torture cases in 13 different venues. In the process of organizing for reparations, we created communities of care. When Anthony Holmes, who talks about how he was just disbelieved for years, is on the stage sharing his experiences with hundreds of people and asking them to fight for reparations, now he and the other torture survivors are being believed, they are being embraced, they are being loved.

We passed out a voter’s ballot guide on the right of reparations. Over half of City Council agreed to support the reparations legislation. Rahm Emanuel initially didn’t win the primary and was in a runoff against Jesus “Chuy” Garcia.

That’s when Emanuel’s administration opened negotiations. But we remember back when Rahm Emanuel and his Corporation Counsel Steve Patton came out and told us, “No, we don’t owe you anything.”

Did we get everything we wanted? No, of course we did not. Were there compromises made? Yes. What I can tell you is that our principle as part of the coalition was that if the torture survivors said they wanted us to take the deal, we would. We reached out to every torture survivor we could find, including those who remain incarcerated. We asked every single one.

We did win an official apology from the City of Chicago for the pattern and practice of torture, financial compensation for some. We were able to create the Chicago Torture Justice Center that has become a hub not only in providing healing around police violence but in thinking out ways of organizing against police violence. The center is located on the south side, the area where people are the most affected and impacted by the violence.

It was the organizing campaign that won these reparations, not a legal battle. Rehabilitation and public education could only have been accomplished through an organizing campaign.

At the May 6, 2021 press conference on the sixth anniversary of the passage of the Reparations Ordinance, we were excited to announce that an art funder has given $500,000 toward building the memorial. The Chicago Torture Justice Memorials has been through an entire process of calling on artists of color to submit bids for designing it and then having a jury composed of torture survivors, art members and members of the public to select the design.

We are now struggling with the city of Chicago to get that memorial. The torture survivors want it located on the south side, where they were tortured. We won’t take no for an answer.

LL: The apologies I’ve read, say, “And now we’re turning a new page.” Of course, torture continues even after they turn that very thin page. The apology is important for the record. I’ve come to understand it that way.

In the coverup of the Laquan McDonald murder in 2014, the mayor refused to release the video that proved he was shot 16 times as he was walking away from the police. Again, it took a series of demonstrations to force the court to order the dash cam video released. More than a year passed before the video revealed the truth and when boxed in, Emanuel issued an apology. How genuine does that feel to anyone?

JM: It meant a lot when George H.W. Bush apologized to the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in concentration camps. I think the apology for us is about creating the dominant narrative. Even if Burge was convicted, you were still going to have people say, “Oh, we’re not sure this happened” or even come out and say, “Well, we think Burge’s got a bad rap.”

Well, what you think is not based in fact. We have an official apology that recognizes this occurred. And that apology is going to launch us into getting a memorial. Since the ordinance passed, we’ve gotten more guys out of prison and we’re fighting to get more out. Even the judges who deny us now say, “Well, torture did occur.” For decades they weren’t willing to say that. Now no one can deny it.

Still Incarcerated

LL: What challenges remain in gaining the freedom of those still behind bars unjustly and reparations for all those who are incarcerated? I understand there are at least 13 identified torture survivors still in prison.

JM: I’m still representing two Burge torture survivors who are behind bars. Burge spent most of his career in Area 2 and engaged in torture there. But in 1986 he became commander of Bomb and Arson, and then commander of Area 3. He brought a lot of his detectives from Area 2 to Area 3.

While the courts now acknowledge that torture occurred in Area 2, they’re not concluding the same thing happened at Area 3. I also think the courts want to say, “Once Burge was fired, the impunity stopped.”

It’s one thing to fire Burge, and that happened because a movement made it happen, but then they should have reinvestigated every case he touched. They never did. No other officers were ever disciplined. We need to educate people about how Burge’s henchmen continued.

Fortunately, I think we are seeing a rupture in our society and it’s far beyond the Burge torture cases. We’re seeing that the whole system of policing is predicated on anti-Black violence. It stems from the slave patrols that existed during slavery. Policing isn’t about safety and freedom from violence.

We need to take the power and resources away from our police departments because they’re not making us any safer. In fact, they’re just bringing more violence.

DF: We need to show people that we don’t get public safety through armed, uniformed and trained shooters, but through de-escalation teams, trauma centers and a quality of life. When you mentioned there’s one trauma center focused on violence within our country, I think of the way tax foreclosures and evictions are carried out in Detroit, a Black city. The threat of water shutoffs and evictions is traumatic.

JM: Critical Resistance is doing groundbreaking work. I think they’re leading the way in figuring out how we can look to alternatives to the system, the Prison Industrial Complex, in terms of thinking about safety and freedom from violence.

Police shouldn’t be involved with traffic violations. We shouldn’t criminalize sex work or drug usage. Even with the legalization of marijuana in Illinois, an article recently reported that arrests of Black people for marijuana possession have increased.

I think the movement is way far ahead of where our institutions are, where our criminal legal system is. It’s not that people are saying, “We don’t want people to be safe or free from violence.” What we’re saying is, “This is not working and in fact, it’s harming people. We need to create alternatives to violence and alternative ways for conflict resolution.”

We still need to obviously push to get people out of prison and we need to get people to understand you don’t have to torture someone to get them to confess. There are so many psychological tactics that are being used that are resulting in coerced confessions. I think we need to re-examine the entire way the policing works, including how we get these confessions.

We need a radical reevaluation of our values, and I think that that includes in the words of Grace Lee Boggs from Detroit, who followed in Martin Luther King’s steps, that radical “revolution of values.” I think that we need to have a radical paradigm shift in the way we think about freedom from violence. I think that that’s one that doesn’t include the police.

An important part of that is the Chicago Public School curriculum. Anthony Holmes, Darrell Cannon and Mark Clements are getting standing ovations when they speak in the schools, they’re the authorities.

Many of these young Black and brown students have been harassed by the Chicago police and look up to the torture survivors as heroes. They see these guys, who were tortured and incarcerated, standing there speaking truth to power. This bond creates a whole other kind of effective quality beyond any material redress we got from the reparations legislation.

July-August 2021, ATC 213

This is an amazing interview with Joey Mogul. It really helps to see how reparations can work. It shows how speaking at schools where people believe what the survivors describe can lead to healing as well as organizing resistance to torture and injustice.