Against the Current No. 213, July/August 2021

-

Infrastructure: Who Needs It?

— The Editors -

Burma: The War vs. the People

— Suzi Weissman interviews Carlos Sardiña Galache -

Afghanistan's Tragedy

— Valentine M. Moghadam -

The Detroit Left & Social Unionism in the 1930s

— Steve Babson - On the Left and Labor’s Upsurge: A Few Readings from ATC

-

Detroit: Austerity and Politics, Part 2

— Peter Blackmer - Chicago's Torture Machine

-

Reparations for Police Torture

— interview with Aislinn Pulley - Diana Ortiz ¡presente!

-

A Torture Survivor Speaks

— interview with Mark Clements -

Torture, Reparations & Healing

— interview with Joey Mogul -

The Windy City Torture Underground

— Linda Loew - Palestine -- Then and Now

-

Palestinian Americans Take the Lead

— Malik Miah -

Zionist Colonization and Its Victim

— Moshé Machover -

Conceiving Decolonization

— David Finkel -

Not a Cause for Palestinians Only

— Merry Maisel -

When Liberals Fail on Palestine

— Donald B. Greenspon - Reviews

-

Immigration: What's at Stake?

— Guy Miller -

Exploring PTSD Politics

— Norm Diamond -

A Life of Struggle: Grace Carlson

— Dianne Feeley -

Living in the Moment

— Martin Oppenheimer

Linda Loew

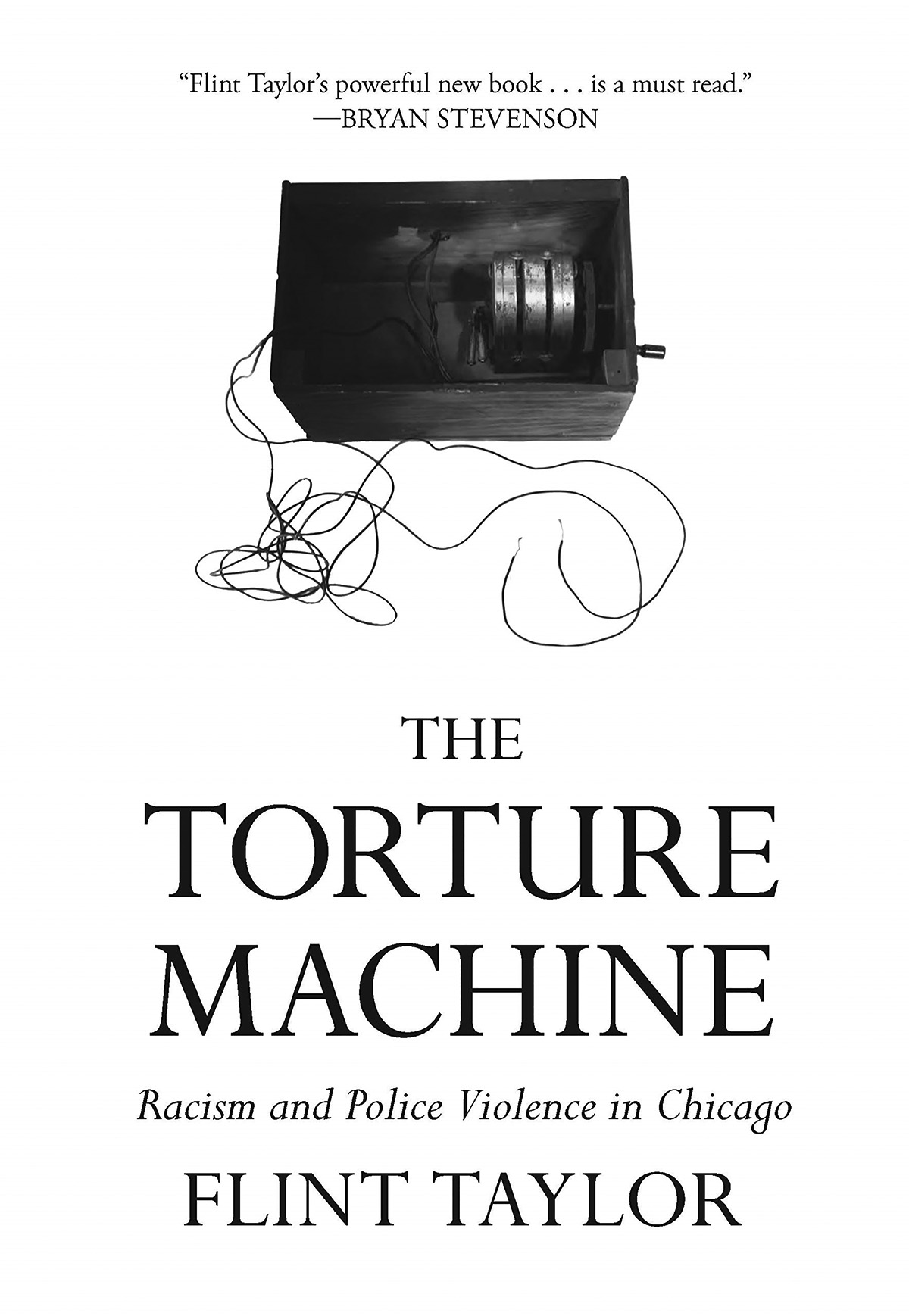

The Torture Machine:

Racism and Police Violence in Chicago

By Flint Taylor

Haymarket Books, 2019 (hardback), 2020 (paperback),

556 pages, $19.95 paperhback.

THE “CITY OF broad shoulders” and architectural gems, Chicago also has a dark chapter in its history: torture of African American men carried out for decades by the Chicago Police Department (CPD). Flint Taylor’s The Torture Machine: Racism and Police Violence in Chicago spans nearly 50 years in more than 500 pages.

The book delivers a harrowing account of the police torture carried out by Commander Jon Burge and the officers he supervised, between 1972 and 1991. With over 120 known victims, mostly African American males, one as young as 13 years old, the book details several cases and the scope of denial and cover-up.

It hails the struggle to prove that it happened, to hold those guilty of torture and its cover-up accountable, and to win justice for victims. It is not easy to read, but important to know.

The opening chapter, “Murder by Night,” recounts the December 4, 1969 assassinations of Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton and leader Mark Clark. Taylor, then a law student, joined the civil suit filed on behalf of the families and survivors of the murderous raid.

He and other young lawyers from the newly founded People’s Law Office (PLO) helped win an unprecedented settlement in 1982. The 13-year suit also revealed the raid to be an integral part of the FBI’s COINTELPRO program. These revelations changed the narrative on the racist nature of police practices in Chicago, setting the stage for the “torture wars” to follow.

“Torture Machine” has two intertwined meanings: one is the electric shock device used on many of the interrogated suspects. “Torture machine” also refers to the system of law enforcement and government (police superintendents, judges and elected officials all the way up to mayor) who were complicit in denying, condoning and covering up crimes. Many lied under oath or delayed justice for victims.

Torture: Vietnam to Chicago

By the time the Hampton/Clark suit was settled in 1982, another reign of terror was underway. The CPD conducted a sweeping “manhunt,” through predominantly African American neighborhoods of Chicago’s south side, kidnapping and arresting suspects for the murder of two police officers. If there was no immediate evidence, they would beat and torture confessions out of their suspects.

The victims and the cops who tortured them fell on two sides of Chicago’s racial divide. In one of the most segregated cities in the nation following the Great Migration of African Americans to northern cities, these neighborhoods suffered decades of deep inequality and rampant neglect in housing, health care, jobs and education.

The victims from these neighborhoods were treated by the system as less than human, not to be believed by their interrogators, the courts, or the public. During one early trial seeking justice for torture victim Andrew Wilson, Judge Duff referred to Wilson as “scum of the earth.” (122)

In contrast, working class whites made up (and still do) a disproportionate number of Chicago’s police force.

Jon Burge had served as a military police sergeant in a prisoner of war camp in South Vietnam during the height of the war. He oversaw interrogations that included murder and torture with electric shock.

Burge returned a “war hero,” and went on to head the Violent Crimes Unit at CPD Area 2, and later Area 3 on Chicago’s south side. Burge and his team were portrayed by the system as hard working cops in high-crime neighborhoods who faced danger every day. Even as the torture was taking place, Burge was promoted from detective to commander in record time.

In the public image, “Burge and his men gave new meaning to the ‘war on crime’ politics gripping Chicago and the nation, churning out an impressive record of arrests, confessions, and convictions that fueled the mass incarceration of young African American men.” (67)

The acts and instruments of torture were varied and rotated at the whim of individual cops. These included suffocation with plastic bags (often typewriter covers,) known in military jargon as “dry submarino,” beatings on the bottoms of feet and on testicles, being handcuffed to the wall or window while being spread over a hot radiator, all while being interrogated.

The legendary “black box” was clipped to suspects’ hands or ears, then cranked like a telephone, sending electrical charges through the victim, causing shocks and injuries to organs, head and hands.

It bore a striking resemblance to torture techniques applied by the U.S. military in Vietnam, in Abu Ghraib Prison in Iraq, and at Guantanamo.

This method was often used last to put the finishing touches on hours of torture in order to extract a confession. A State’s Attorney would wait in an adjacent room, ready to grab the signed confession.

The Iceberg Surfaces

The decades-long case of Andrew Wilson is a central thread through the book. Wilson endured many of the practices in the Burge torture playbook. The judge in his first trial refused to allow documents that supported Wilson’s torture claims. He was found guilty by an all-white jury and sentenced to death.

Eventually granted a new trial, the civil suit he also launched for damages, taken on by Taylor and a PLO legal team, led to investigations into the torture of many other victims.

The initial victims turned out to be the tip of the iceberg on torture carried out in CPD Areas 2 and 3. Each investigation led to others. Taylor and his team traveled to all corners of the state to take testimony.

Another compelling example is Darrell Cannon. His testimony given from prison described being taken to a remote area of Chicago’s southeast side in 1983, subjected to electric shock on his genitals and mock execution with a shotgun held in his mouth, while racial epithets were shouted at him.

Despite vivid testimony at his first trial and again in 1993 and 1994, his conviction stood. He was resentenced to life in prison, although his confession was based on torture. These rulings were eventually overturned by a Judge Wolfson in 1997, who declared that “…in a civilized society torture by police officers is an unacceptable means of obtaining confessions from suspects.” (238)

Despite being granted a new trial, due to complications, Cannon would remain in prison until 2007. The physical, psychological, and legal nightmare endured by Darrell Cannon repeats in the lives of many others.

Several cases progressed at the same time. The names of all victims are too numerous to list here. All their suffering matters, regardless of their status of innocent or guilty of alleged crimes. Together, their experiences formed the basis for charges of a “racist pattern and practice” that was difficult to prove and resisted by the system, until the mountain of evidence was too huge to bury or deny.

A major breakthrough came in 1990 with the investigative journalism of John Conroy, writing for the weekly Chicago Reader. His article “House of Screams,” detailing the torture of Andrew Wilson, was read by a large audience and captured the attention of Amnesty International. AI eventually brought international attention to police torture in Chicago.

Global conferences and reports took up the cause. Lawyers for torture survivors as well as Chicago community leaders presented cases before the UN Committee Against Torture (UNCAT) as well as the Human Rights Committee in Geneva in 2006.

One of the reports led to the first call for reparations as a vehicle for bringing justice to torture victims. This international spotlight was huge, coinciding with growing protests in the streets of Chicago, and increased media coverage around the country.

The Importance of Protest

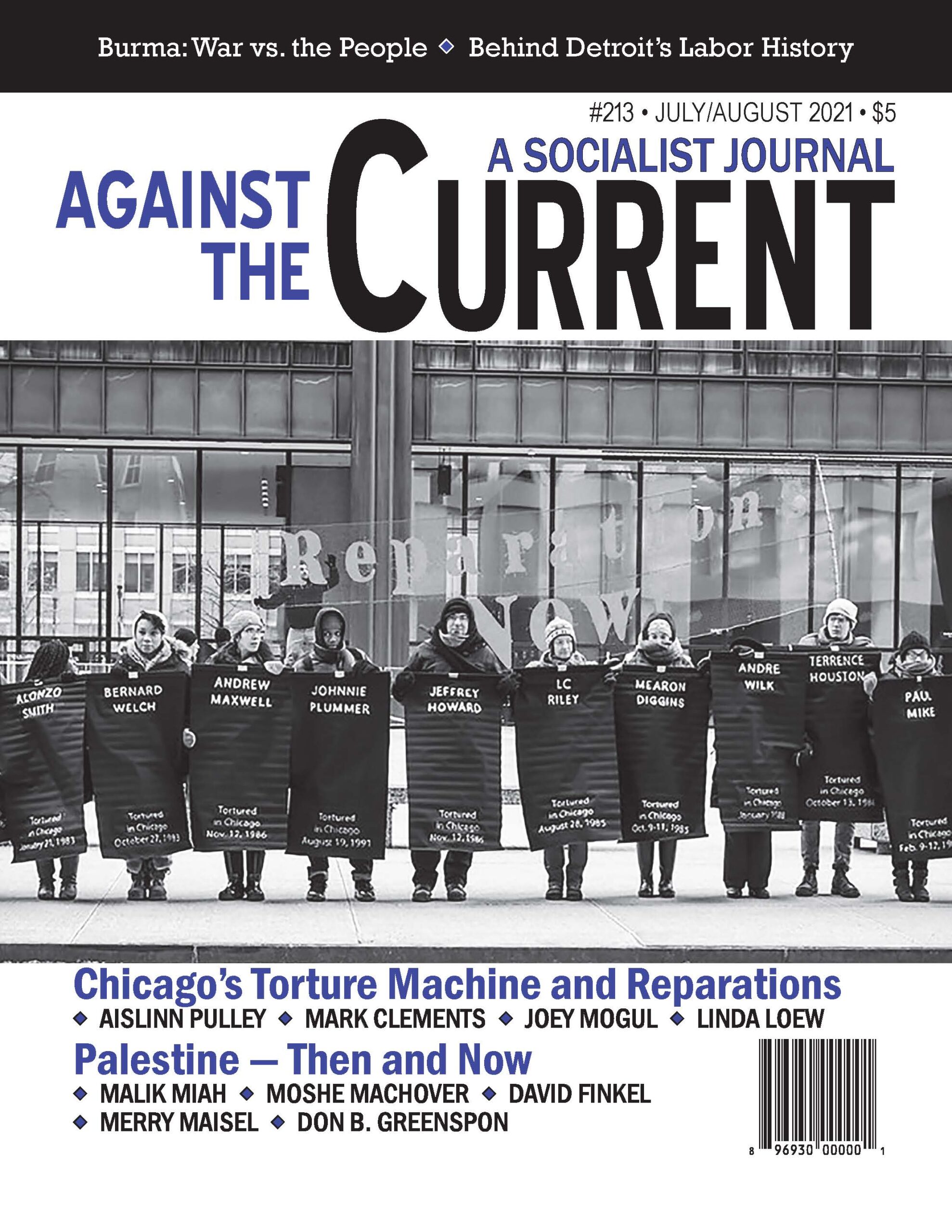

”Out of the Court and into the Streets” (Chapter 8) underscores the role of community protests, including demonstrations led by the Task Force to Prevent Police Violence and the Citywide Coalition Against Police Abuse.

By 1989, this coalition of 29 groups led a demonstration at police headquarters, declaring that cases of racist police abuse were on the rise all over the city. They delivered a petition to Mayor Richard M. Daley and Police Superintendent Martin, raising for the first time the idea of reparations from the CPD to the victims of police torture.

More marches, tribunals on campuses, protests in and outside courtrooms, all contributed pressure. There was mounting irrefutable evidence of torture that the political machine could no longer cover up. Witnesses came forward, including a few from the ranks of the police.

The torture wars had their very own “Deep Badge,” an unnamed detective sending documents that corroborated the torture that transpired in Area 2 and Area 3 interrogations. Another detective, Frank Laverty, also busted the code of silence, coming forward about the frame-up of George Jones, an innocent young man just out of high school, who spent five painful months in Cook County Jail for a crime he did not commit.

Laverty helped reveal the existence of “secret (aka street) files” which led to Jones’ release and later exonerations of others falsely convicted. Demoted and shunned by his fellow detectives, Laverty’s fate reflects the atmosphere of fear and intimidation facing cops with a conscience.

The crisis of police violence is not about “bad apples.” It is an institution formed and mired in centuries of systemic racism. Those with a conscience often have to leave the force to preserve their humanity.

Additional key witnesses were finally allowed before juries. Among them was Dr. Jack Raba, Director of Medical Services at Cook County Jail, whose earlier requests for investigations of torture at Area 2 had been ignored. Joining him were experts in post-traumatic stress disorder. Many torture survivors continue to struggle with PTSD.

Solidarity was also important inside the prisons. A group of prisoners, previously unknown to each other, began a study group through which they discovered that each had been victims of torture. They became the “Death Row 10.”

Aided by the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, their cause was boosted by a major Chicago Tribune article featuring one of the wrongfully convicted, Aaron Patterson. In January 2003, just hours before leaving office, Illinois Governor George Ryan declared a moratorium on the death penalty, commuting the sentences of all current death row inmates to life in prison or less, the largest emptying of death row in history. This included the Death Row Ten.

In an impassioned speech, Ryan quoted U.S. Supreme Court Justice Blackmun’s 1994 assertion that “I can no longer tinker with the machinery of death.” Ryan added “The legislature couldn’t reform it; lawmakers won’t repeal it. But I will not stand for it. I must act. Our capital system is haunted by the demon of error.“ (295-6)

Journalism professors and students at Northwestern University’s Medill Innocence Project played an important role in the lead up to this historic act by Governor Ryan.

In March of 2011 Illinois Governor Pat Quinn signed into law the abolition of the death penalty, and he commuted the death sentences of another 15 Death Row inmates to life in prison.

Justice Delayed

While Commander Burge was suspended in 1991, and fired in 1993, his conviction did not come until 2010. After years of denials, lies, invoking of the Fifth Amendment and being aided by judges to elude justice, Burge was finally convicted of perjury and conspiracy to obstruct.

Despite a regrettable statute of limitations on conviction for torture, and a prison sentence of a mere four years, Burge’s conviction helped open doors to admission of torture evidence in several cases.

In January 2012 the Chicago City Council passed a unanimous resolution making Chicago the first U.S. city to formally oppose all forms of torture. Real justice still lagged behind this largely symbolic gesture.

While no elected official was ever held legally accountable for the crimes committed on their watch, the city itself was finally forced to reckon with and pay for the torture inflicted by Burge and his cohorts.

On May 6 2015, the Chicago City Council unanimously passed the Reparations Ordinance, a historic and unprecedented measure, first in the nation. It was drafted by Joey Mogul, a co-lead counsel in several of the cases representing Burge torture survivors, as well as a founding leader of the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials.

The CTJM helped spearhead a multi-pronged, multi-racial, multi-generational organizing campaign to bring material justice to torture survivors. (For details on the ordinance, see interviews with Aislinn Pulley, Mark Clements and Joey Mogul in this issue of Against the Current.)

Burge’s conviction and time served, the elimination of the death penalty, a series of exonerations, commutations, and ultimately the Reparations Ordinance are victories which also proved the fact of torture. The “black box” may have ended up at the bottom of Lake Michigan, tossed overboard from Burge’s aptly named boat, the “Vigilante,” and torture by Burge ceased, but torture did not end in Chicago.

As recently as 2020, there were regular protests to close the Homan Square detention center, a police “black site” where more than 10,000 mostly black and brown men were arrested and detained (“disappeared.”)

As revealed by a series of articles in The Guardian newspaper, detainees, including political protesters, were held for hours or days, without access to lawyers, bathrooms, or water. Many suffered some of the same physical abuse as in the Burge days. Lasting for more than 15 years, legal cases continue for victims of abuse at this location.

A Widening Discussion

During and since the trial of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, there have been an average of three racially motivated police shootings every day. Videos of police violence and the resulting public outrage have transformed the national conversation.

There are continued calls for investigations of pattern and practice in police departments, no-knock search warrants (like the one where police murdered Breonna Taylor in Louisville), and split-second-decision defenses.

The Chauvin conviction, widely hailed as a victory, is an important but small step on the long road to justice. An important Chicago victory is the removal of police from public schools for the remainder of the 2020-21 school year.

Even before that announcement, 55 Chicago high schools were drafting safety plans based on restorative justice and crisis management, to be reviewed by local school councils for implementation next year. If they’re successful, the school district would spend $24 million over the next three years to address student trauma and mental health.

Given decades of disinvestment in public education, massive closure of schools and mental health clinics, this amount is a drop in the bucket. To keep things in perspective, Chicago’s Mayor Lori Lightfoot used $281.5 million of federal COVID-19 relief funds on Chicago Police Department Payroll costs.

Nothing can bring back lives lost or decades spent behind bars for those wrongly convicted. Reparations begin to address the physical and psychological scars suffered by victims and their families. But an estimated 100 survivors still languish behind bars.

Many involved in the mass mobilizations to demand justice are beginning to grapple with a growing understanding that there will never be full justice until the deeply systemic racism in all realms of society is dismantled.

This means transformative change not only with police and prisons, but in health care, education, housing, jobs and the environment. A range of ideas are being examined and debated from calls to defund the police, abolish the police and reimagine public safety.

The fight for justice for torture victims and all victims of racism continues. Flint Taylor’s call to action in the closing pages of his book is absolutely true: ¡La Luta continua!

July-August 2021, ATC 213