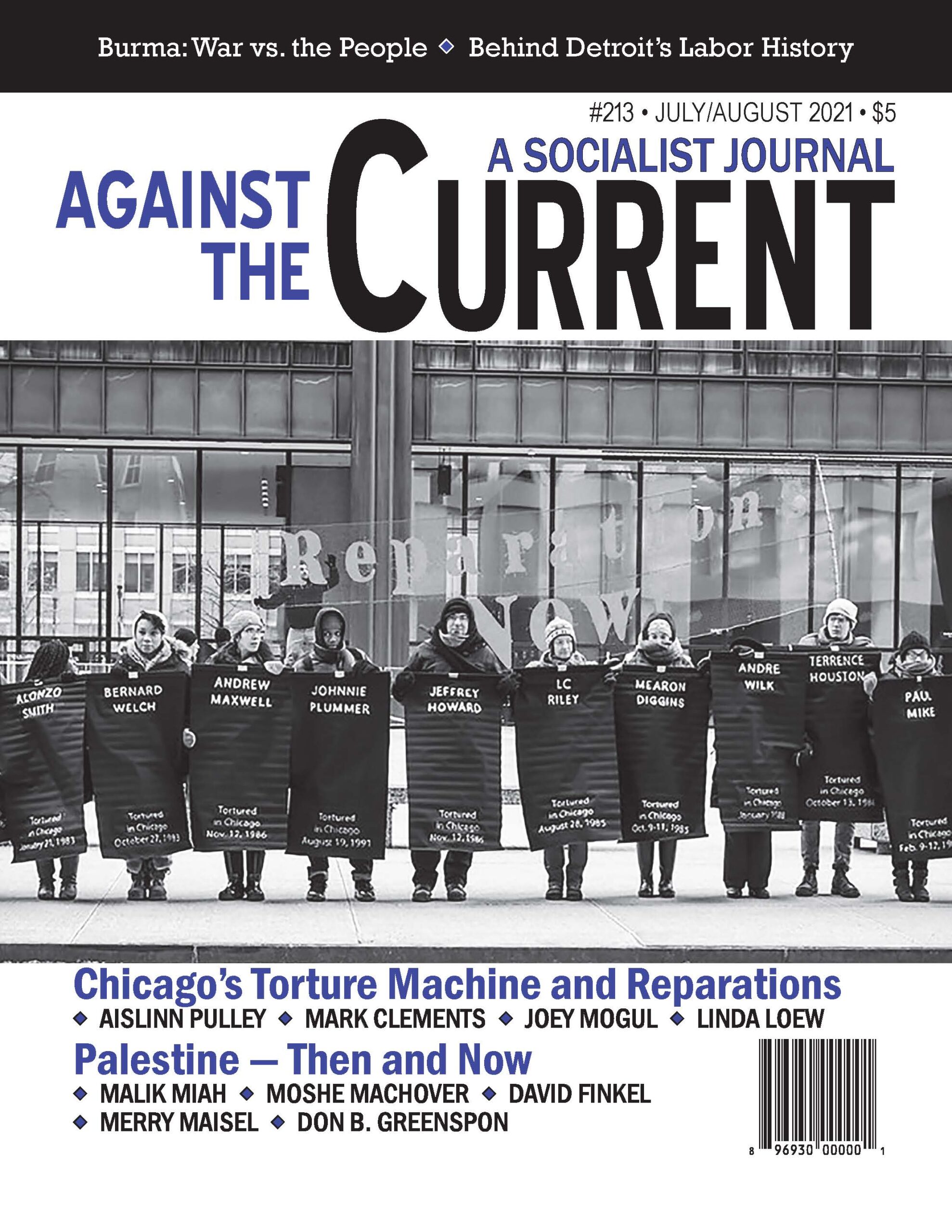

Against the Current No. 213, July/August 2021

-

Infrastructure: Who Needs It?

— The Editors -

Burma: The War vs. the People

— Suzi Weissman interviews Carlos Sardiña Galache -

Afghanistan's Tragedy

— Valentine M. Moghadam -

The Detroit Left & Social Unionism in the 1930s

— Steve Babson - On the Left and Labor’s Upsurge: A Few Readings from ATC

-

Detroit: Austerity and Politics, Part 2

— Peter Blackmer - Chicago's Torture Machine

-

Reparations for Police Torture

— interview with Aislinn Pulley - Diana Ortiz ¡presente!

-

A Torture Survivor Speaks

— interview with Mark Clements -

Torture, Reparations & Healing

— interview with Joey Mogul -

The Windy City Torture Underground

— Linda Loew - Palestine -- Then and Now

-

Palestinian Americans Take the Lead

— Malik Miah -

Zionist Colonization and Its Victim

— Moshé Machover -

Conceiving Decolonization

— David Finkel -

Not a Cause for Palestinians Only

— Merry Maisel -

When Liberals Fail on Palestine

— Donald B. Greenspon - Reviews

-

Immigration: What's at Stake?

— Guy Miller -

Exploring PTSD Politics

— Norm Diamond -

A Life of Struggle: Grace Carlson

— Dianne Feeley -

Living in the Moment

— Martin Oppenheimer

Martin Oppenheimer

Our Sixties:

An Activist’s History

By Paul Lauter

University of Rochester Press, 2020, 226 pages,

$29.95 hardback.

WHEN THIS STORY begins in 1957, Paul Lauter had never heard of Conscientious Objectors. With a Ph.D. from Yale in literature, he had little awareness of Black writing, or Black history. Seven years later he was teaching both subjects in a Freedom School in Mississippi and was Director of Peace Studies at the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), which is where we met (I was Assistant Director).

Now retired, a distinguished professor emeritus of literature at Trinity College — and best known perhaps as co-founder with Florence Howe of The Feminist Press in 1970 — Lauter looks back to those years as a period of “growing up” politically and personally.

The political part goes from his first firing for union and anti-ROTC activity as a young professor, to teaching and in this book writing about “the movement.” “While the sixties movements did not revolutionize the United States,” he says, “they produced valuable organizations and lasting changes, of which we are properly proud.” (6)

As Lauter moves back and forth in the 1960s and ’70s between educational projects, civil rights and antiwar activities, he seems constantly to be asking: How is this work achieving change?

As for the personal growth part, there are his relationships with women including several marriages, and his interactions with feminism. Throughout, he is also asking what should he be doing? Full-time movement activist? Full-time educator? Academic trouble-maker?

Today he identifies as a socialist. Whatever he calls himself, he’s always had the right enemies, from sexual Puritans to uptight Lit Profs to sectarian ultra-leftists to the Klan.

Commitments and Identity

There are three themes contained within this political autobiography: His commitments to the anti-war movement, to civil rights, and to anti-authoritarian teaching.

Through the first half of the book we watch as Lauter struggles with his own identity as a liberal, while at the same time trying to find his proper niche within the three movements.

He participated in Freedom Summer, the great voter registration campaign in Mississippi in 1964, where he taught in alternative “Freedom Schools.” He practiced a Paolo Freirian “listening” form of education, related to Rogerian “student-centered” teaching.(1)

A year later he and Florence Howe (1929-2020), his partner from the late 1960s until the mid-eighties, helped staff a teacher training institute at Goucher College devoted to the same principles.

In those days it was possible to find employment as a lit professor with no hassle and by then he had landed a job at Smith College. There he helped start up a Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chapter.

When his curriculum proposals challenging traditional teaching methods got a cold response, he decided to commit himself to movement work. By chance a job as Peace Education Secretary in The American Friends Service Committee’s Chicago office opened up and he jumped at it, especially because it gave him time to work in the SDS national office.

Resistance to the war was center-stage for both AFSC and SDS by the Fall of 1965. Lauter busied himself with draft counseling while at the same time trying to figure out how to foster broader resistance to the war.

He increasingly found his identity as a liberal and advocate for nonviolence challenged by the fact that the U.S. government under Lyndon Johnson remained unmoved by massive demonstrations. He soon came to wonder why speakers talked of the betrayal of liberal values when the American war was really about imperialism.

But about a year after his move to Chicago, Lauter suddenly found himself out of a job. It had dawned on the AFSC bureaucracy that he was living in sin with Howe, which in those days did not sit well with a Midwest Quaker organization.

Problems of Innovative Education

Soon Lauter and Howe were drawn into a project intended to turn an existing Washington, DC segregated Black and poorly-funded elementary school, the Morgan School, into an integrated school with increased resources and “…a new and imaginative curriculum.” (117)

Antioch-Putney’s Grad School of Education would provide interns. The school was to be controlled by a bi-racial Community Council, all under DC’s Superintendent of Schools. Today this would be called a Charter school.

When the Project Director failed to show up, Lauter found himself de-facto principal although he was not certified and had not been near an elementary school for almost 25 years. He soon learned that the words New, Resources, Imaginative and Community (within an existing school system) would not work. Chapter Seven, “Visions of Freedom School in DC,” is a text on what can go wrong. For educators this story is alone worth the price of the book.

Briefly, there were conflicts that within a year led to Antioch’s pulling back and the firing of Howe on the accusation of nepotism(!) Lauter’s firing soon followed.

Beyond a lack of an integrated curriculum and adequate training for white interns unaccustomed to teaching low-income Black students, there were conflicts about basic goals. The regular Black teachers were not on board with experimentation. They (as well as many Black parents) thought the kids needed discipline.

This ran into conflict with the white parents who were seeking an innovative setting but also worried about the emphasis on Black pride, something that had not been a problem in Mississippi’s Freedom Schools.

Moreover, “At the Morgan Community School, community ‘control’ did not translate into community service,” so parents had little motivation for involvement in the school, plus they were “busy trying to make a living.” (123)

Resist and NUC

In October 1967 a “Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority,” signed by such well-known anti-war figures as Noam Chomsky, Paul Goodman and Dr. Benjamin Spock, was published. It’s reprinted in the book as Appendix A. (227ff)

A mass draft-card turn-in at the Justice Department on October 20 was the starter event for Resist, the organization that came out of the “Call.” Lauter became National Director. On the 21st the Resist crew joined the March on the Pentagon, famously described in Norman Mailer’s The Armies of the Night (1969). Then the “Boston Five” were indicted on charges of “conspiring to counsel young men to violate the draft laws.” (141)(2)

Resist soon changed its mission from support to the Five and other draft resisters to a hub for funding many social change projects, a kind of United Fund of the Left. It continues its work today.

Direct action in the form of physical attacks on draft board files now made headlines. Lauter and Howe joined the Baltimore Defense Committee, which supported actions around the trial of the “Catonsville Nine.”

Lauter does not provide details, but in summary the Nine, who burned draft records on May 17, 1968, included two fairly well-known Catholic priests, the Berrigan brothers Philip and Daniel. Philip was already facing trial as part of the “Baltimore Four” for burning draft records at the City Customs House the prior October.

After another year with Resist, Lauter returned to teaching in the Fall of 1969, at the predominantly white working-class University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). There he helped initiate the New University Conference (NUC), a nationwide coordinating group for radical caucuses in different academic fields, a kind of SDS alum association.

These caucuses were soon widespread in such varying fields as economics, sociology, political science, geology, etc. In almost every case they created their own journals as alternatives to “establishment” journals. Many still exist, among the only living institutions stemming from the New Left.

NUC chapters were intended to coordinate radicals from different fields within a college or university in attempts to “transform universities and the intellectual work done within them.” (158) Unfortunately, internal disputes resulted in NUC dissolving itself in 1972, and shipping its archives to the University of Wisconsin. This left campus chapters without national coordination or support, and many collapsed.

In addition to NUC work, Lauter also tried getting his UMBC classes to engage in working collectively, earning collective grades. When the more radical students demonstrated against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia in April, 1970, Lauter was on the scene helping with strategy and picketing. At the close of his second year he was fired.

Soldier Organizing, The Feminist Press

Miraculously, again “opportunity emerged from adversity.” (169) Lauter soon found himself at the “reins” of the United States Servicemen’s Fund. This innocuous-sounding organization was in fact an antiwar group that supported GI coffeehouses, GI underground newspapers, helped GIs who refused deployment to Vietnam, and mounted anti-war entertainments leading up to the famous “FTA” shows.

These were anti-war alternatives to Bob Hope’s overseas shows for the United Service Organizations (USO). Lauter does not describe the shows, but they consisted of skits and music, often starring Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland. (There were some coffeehouses unrelated to the show also named FTA.(3)) Almost needless to say, FTA means Fuck the Army although there are milder interpretations.(4)

Lauter intersperses his own story with considerable detail about the internal conflicts of organizations like NUC and the USSF, and the broader strategic disputes within the anti-war movement. He describes “…disagreements about how we got in led to harsh differences about how to get out.” (180) Run antiwar candidates? Marches? Sabotage military-related facilities including draft boards? Advocate negotiation, or “Out Now?”

This led to more acrimony and splits than we’d like to remember. Still the killing went on and on in Southeast Asia, to Lauter’s dismay and frustration. From his cockpit spot with USSF he became aware of how U.S. troops were becoming “an increasingly unreliable force.” (177)

At the same time there was a war at home: the 1968 Chicago Democratic Party Convention police riot, murders of Black Panthers, Kent State, Jackson State, the Weather Underground, chants of “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, the NLF is gonna win” (even at scholarly conferences).

The fragmentation of the antiwar movement, sectarian competitions especially within the student left, the collapse of SDS in 1969, and the USSF’s decline led Lauter to a period of battle fatigue. He left the USSF, or perhaps vice-versa, sometime in late 1970. We are left guessing about the circumstances.

Soon Lauter, still together with Florence Howe, was developing the Feminist Press, established in that Fall.

His deep love of literature is apparent throughout the book as he joins the fight to extend and even overturn “the canon.”(5) The Press’s objective was to shine a light on “lost or forgotten” literature by such women writers as Rebecca Harding Davis (Life in the Iron Mills, 1861) and Josephine Herbst with her “proletarian” novels and reportage from the 1930s.

One of the first books re-published by the Press was Agnes Smedley’s Daughter of Earth (1973, orig. 1929), a slightly fictionalized autobiography. Smedley had lived in China for many years and was very close to major Soviet and Chinese Communist figures. She died in 1950.

In 1974 Lauter was part of a delegation to the People’s Republic of China, where he gave the Press edition and archival materials concerning Smedley to Chinese officials. Lauter clearly had a soft spot for Smedley and “Red China.” The delegation was given the appropriate tours, which “registered positively with us.” (164)

At that time Mao’s “Cultural Revolution” was winding down, but somehow he would not learn until later about “the violence and stupidity” of that period, nor apparently of the famine during the “Great Leap Forward” of 1958-62.

In 1972 Lauter joined Howe on the faculty of the State University of New York (SUNY) Old Westbury. This was one of a number of experimental colleges founded around that time to “open access for an unusually diverse student body” or to put it bluntly, to “deal” with student Blacks and reds by hiring hip professors and cool administrators.

Could Old Westbury become a “movement outpost?” Could Lauter assist in “establishing a curriculum informed by freedom school values? (199)

He was not sure but threw himself into it, even getting active in the SUNY’s American Federation of Teachers (AFT)-affiliated United University Professors. People were needed to implement the contract, so Lauter became grievance officer. Ultimately he moved up to UUP vice-president.

In an ironic turn of events, some Feminist Press workers wanted to unionize and asked his support. Howe was opposed to the unionization effort. Lauter does not tell us the outcome. When he ran for statewide UUP president he lost by two votes, perhaps due to his position in the Press’s management. He then dropped his union activities to turn his attention to the academic side of Old Westbury.

Constructing American Studies

Lauter’s slot was in American Studies, a new program with women’s studies, labor studies, U.S. history and literature “tracks.” His colleagues were stars of left academia. On top of working with the Press, he and Howe were now “pushed” into chairing the program.

Still, he wondered whether it all mattered. “Perhaps I should be spending more time in the street and on the picket line than in the library.” Well, he answers, no. It seems that “what you read about, who and what you see on screens…helps shape what you find important or even visible.” (207)

There is a “conjunction” between events and literature; writers have been reshaping consciousness for ages. He cites James Baldwin, Gwendolyn Brooks, Claude McKay and of course Life in the Iron Mills. This kind of canon-challenging material needed anthologizing. and so Lauter embarked on what would become The Heath Anthology of American Literature (five volumes, the first appearing in 1989).

By that date he had left Old Westbury and moved to Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut where among other projects he created a course on the sixties and began work on Our Sixties.

Lauter provides useful background and intimate details about many events and organizations. Movement veterans with an interest in the educational wars of the sixties and seventies will find Lauter’s book especially interesting. He has much to teach younger activists concerning movement dynamics.

His narrative, however, is often hard to follow due to his peripatetic personal and organizational life. There are many digressions, which add to the difficulty. Inserting more dates would have helped. He leaves the conclusion of a number of events (such as his departure from the Feminist Press) dangling or short of detail.

There are simple errors: It is “Marty” Ehrlich on page 160 (but Howard, correctly, in a footnote), and sin of sins, the incorrect spelling of Max Shachtman. The book would have profited with more careful editing (at a University Press no less).

Concluding his personal and political retrospective, Lauter says that despite defeats, disappointments and the persistence of oppression and despotism, “I remain optimistic…I have seen the movement’s own discord, our aspirations diminished, our hopes forgone. But I have also seen people rising up, again and again, like sunflowers in a great field.” (226)

Notes

- Carl Rogers, On Becoming a Person (1956), ch. 15, where it is described by a student participant.

back to text - They were: Michael Ferber, Dr. Benjamin Spock, Rev. William Sloan Coffin, Mitchell Goodman, and Marcus Raskin. All but Raskin were found guilty, though in the end none served time.

back to text - Martin Oppenheimer (ed.) The American Military, (Transaction, 1971) 99. GI organizing is covered in this book.

back to text - The first show was near Ft. Bragg, NC and then played in the vicinity of numerous U.S. military bases. It then went on a one-month tour of bases in Hawaii, the Philippines, Okinawa and Japan, protesting U.S. bases along the Pacific Rim. The show ended after this run. The documentary FTA was withdrawn from theaters very quickly, possibly due to a dispute with Fonda. Lauter does not elaborate. Segments appear in another doc, Sir! No Sir! FTA is available on DVD now.

back to text - Sometimes referred to as the Western Canon or “high culture” (white and European/U.S.A.) from the Greeks onward. It is a highly contested field to say the least. A view of the debate can be found in Rachel Poser, “The Iconoclast,” The New York Times Magazine Feb. 7, 2021.

back to text

July-August 2021, ATC 213