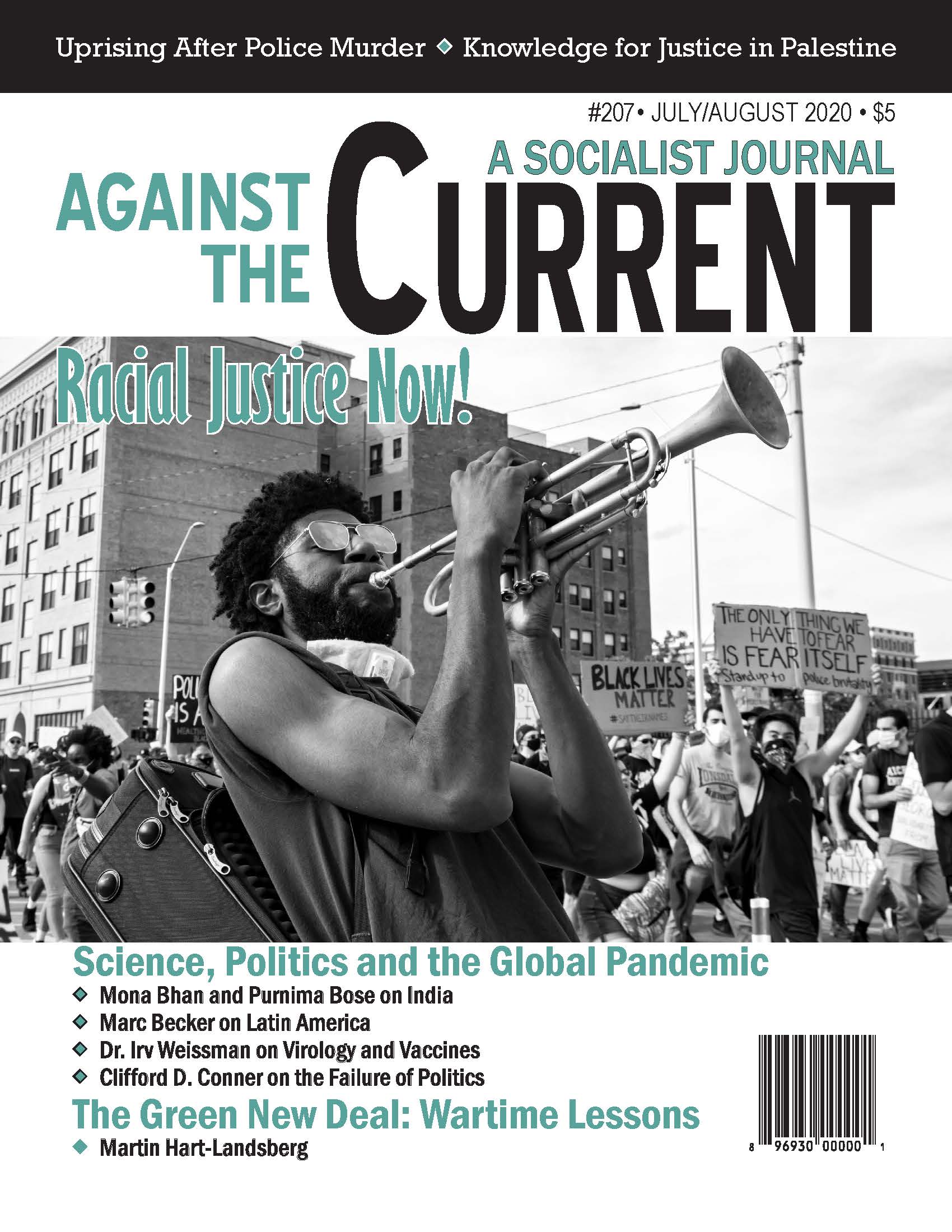

Against the Current, No. 207, July/August 2020

-

"Normal" No More

— The Editors -

U.S. Erupts with Mass Protests

— Malik Miah -

Producing Knowledge for Justice, Part II

— ATC interviews Rabab Abdulhadi -

Lessons from World War II: The Green New Deal & the State

— Martin Hart-Landsberg -

White Supremacy Symbols Falling

— Malik Miah -

The Brotherhood of Railway Clerks

— Jessica Jopp - The Pandemic

-

Authoritarianism & Lockdown Time in Occupied Kashmir and India

— Mona Bhan & Purnima Bose -

Ending the Lockdown?

— Mona Bhan and Purnima Bose -

The Virus in Latin America

— Marc Becker -

Science, Politics and the Pandemic

— Suzi Weissman interviews Dr. Irv Weissman -

What We Need to Combat Pandemics

— Clifford D. Conner - Reviews

-

Clarence Thomas's America

— Angela D. Dillard -

Homeownership and Racial Inequality

— Dianne Feeley -

Anti-Carceral Feminism

— Lydia Pelot-Hobbs -

Half-Life of a Nuclear Disaster

— Ansar Fayyazuddin and M. V. Ramana -

Can the Damage Be Repaired?

— Bill Resnick -

A Lifetime for Liberation

— Naomi Allen

Angela D. Dillard

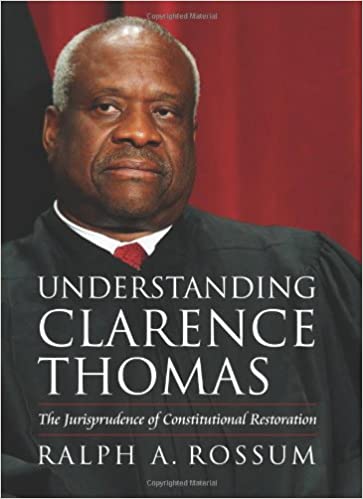

Understanding Clarence Thomas:

The Jurisprudence of Constitutional Restoration

By Ralph A. Rossum

Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2014, $45 hardcover.

The Enigma of Clarence Thomas

By Corey Robin

New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019, 320 pages, $30 hardcover.

IN A WORLD where everyone had read Wilson Jeremiah Moses’s classic text The Golden Age of Black Nationalism, Clarence Thomas would be less of an enigma. Maybe.

As the country’s longest-serving Supreme Court Justice, Thomas deserves to be better understood. But so, too, does Black Nationalism. The term conjures up images of Black fists raised in defiant protest against racism, of afros and machine guns, of Black pride, Black identity and the romance of ancient African origins.

In the popular imagination, Black Nationalism — like Black Power — is rooted in the rejection of “white” values and Eurocentric culture, and expressed in the desire to separate either physically or culturally.

In The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, Corey Robin is counting on readers coming to his provocative biography with this historical film flickering in their heads. In his Introduction, Robin begins to outline Thomas’s remarkable career, from the early years as the new occupant of Thurgood Marshall’s “black seat” on the high court, to the middle period as the “Tea Party” Justice during the Obama years, to today’s glory days in Trumpworld.

For the past 29 years Thomas has written, concurred and dissented on a host of influential opinions ranging from First and Second Amendment issues, to abortion, to policing and probable cause, to LGBT rights and economic deregulation. Throughout he has been engaged in a decades-long conversation about what the Constitution says and how it ought to be used. He has also cultivated a veritable army of law-clerks — more than any other justice in the Trump era — who have been cumulatively reshaping the American judiciary.

Robin informs us that ten of his former clerks “hold high-level positions” in the Trump administration or “have been appointed to the Offices of the United States Attorneys.” (2) Eleven more have been nominated to the federal bench, and an additional seven to the Court of Appeals.

Thomas, in short, has become an institution. And if that weren’t enough for a Black man in America: “Thomas is also a black nationalist.” (2) The line is meant to be jarring and jolting, out of step with the sweep and scope of the Justice’s influence. Roll the Black Power tape.

What is Black Nationalism?

Black Nationalism has always been a complicated body of ideas and beliefs, which is why the work of Wilson Moses is so useful. Over four decades ago, Moses argued that during its “golden age,” from the 1850s to the 1920s, Black Nationalism became wedded to European and American separatist doctrines and, ironically, emerged as a vehicle for the assimilationist values of Black, especially Black American, intellectuals.

In portraying this much-earlier and more-genteel form of Black Nationalism, Moses explores the political thought of Alexander Crummell, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and the National Association of Colored Women as well as the literary output of Sutton Griggs and Martin Delany, to argue that it was ultimately a conservative — rather than a radical — political formation.

How does it change the story to know that Black Nationalism, whatever it became in later years, was born conservative?

Robin is well aware of Wilson Moses’s arguments and is admirably versed in the work of Black scholars who have plowed, seeded and nurtured the field in the years since the publication of Moses’s controversial treatise. Indeed, one of the strongest features of the biography, apart from the rigorous research and close reading of his subject’s enormous judicial output, is Robin’s serious engagement with African-American intellectual and political history.

This is far from a superficial treatment and is often appropriately nuanced. For example, Robin claims to be less interested in the “inherently conservative nature of Black Nationalism” (a la Wilson Moses), and much more invested in the “overlap between black conservatism and black nationalism,” which is a hard distinction to grasp, albeit a crucial one for Robin’s subsequent analysis.

And he is absolutely right that Black Nationalism is embedded in the “deepest tradition” of Black political thought and that it can be found on either side of the political spectrum. (6)

What makes Thomas unique is his institutional location. As Robin puts it: “This country has seen black conservatives. It has seen black nationalists. It has seen conservative black nationalists. It has never seen a conservative black nationalist on the Supreme Court.” (7)

The Supreme Court Justice as Black nationalist is a nice hook, but does this really help us to understand the “enigma” of Thomas?

Nationalist and Conservative

The narrative of Clarence Thomas’s affinity for Malcolm X and Black Power ideologies in his college years at Holy Cross, where he helped to organize the school’s first Black Student Union, are well known. Aspects of his political biography even became a heated topic in its own right during his 1991 confirmation hearing.

At the same time, there has been a general assumption that he moved away from the militant race-conscious nationalism of his youth, into a “mature” set of political assumptions that led him to the Republican Party and the conservative movement.

Many on the right believe that Malcom X is part of what Thomas left behind; many on the left view any attempt by Thomas to lay claim to Malcolm X as crass political appropriation. In one memorable instance Amiri Baraka compared Thomas and other Black conservatives who emerged from the crucible of the 1960s to “pods growing in the cellars of our politics.” (Baraka quoted, 92)

Writing from the perspective of “interpretation and analysis” as opposed to “objection and critique,” Robin largely eschews these kinds of ideological pot-shots. (15) Instead he treats Thomas as an honest narrator of his own life, beliefs and experiences. Ultimately, he portrays Thomas as less of a pod and more of a time bomb.

Robin knows that Thomas can be both a (Black) nationalist and a (Black) conservative, and that both terms carry a distinctive resonance within African-American political culture. Like other members of this tradition, Thomas promotes individual and collective forms of self-help as essential for Black advancement, and believes that government interventions (aka entitlements and “handouts” from the Labor Department and elsewhere) damage their recipients and dump them into a vicious cycle of dependency.

Life on the government dole is said to make Black people and poor people weak and dependent, unable to compete for their rightful place within American society. And, according to this culture of dependency thesis, welfare corrodes their values.

Thomas believes, further, that the conditions facing African Americans were substantially better in terms of dignity and self-respect before the end of legal segregation in the United States. This “when we were colored” nostalgia for an era of Black businesses, churches and institutions is not at all uncommon within Black political culture.

Yet the depth and breadth of Thomas’s anti-integrationism, if Robin is correct, is a much darker and more sinister landscape. Mining hundreds of speeches and interviews, Robin argues that the Rosetta Stone to Thomas’s brand of conservatism is his understanding of race. Here is where things get interesting and . . . a little weird.

Thomas is anti-integration not only because he believes that segregation created a healthier institutional environment for African Americans, but also because of the distance it established between Blacks and whites both physically and emotionally.

On numerous occasions Thomas has shared stories about the personal sting of racism, and he has long believed that its origins are “unknowable.” In his view, racism is far from transient, to be overcome as part of a doctrine of African-American advancement and American reform. On the contrary, racism is a permanent feature of American society. Assimilation is futile.

Years ago, the legal scholar and social critic Derrick Bell argued that acceptance of the permanence of American racism — see his 1993 Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism — was a crucial part of crafting a mature understanding of response to the conditions under which all Americans live.

If Robin is right, Bell and Thomas both accept this reality but it led them in very different political directions. It pushed Bell toward the center-left and a belief that progressive change, under the right set of conditions, was possible; it pulled Thomas to the right — the hard right.

Both Bell and Thomas — and Malcolm X — might critique various forms of liberal social policy for reflecting assumptions about Black victims and white saviors, but Robin’s argument is that Thomas takes this position much further.

In Robin’s reading of Thomas’s worldview, all attempts by white liberals to “help” Black people are nothing more than an expression of their own combined privileges of race and class. This form of self-serving paternalism reinforces, over and over again, the stigma of blackness in ways that promote and solidify visions of white supremacy.

“So, too, does white conservative policy and ideology!” readers might be inclined to shout. In this regard, Robin argues, the racism of white conservatives is to some extent more acceptable to Thomas because it is more honest. It is also in line with his endgame vision.

For Thomas, liberals and conservatives may be equally racist, but conservatives use their racism in ways that redound to Black “benefit” — to stand against equally “racist” and damaging policies such as welfare, affirmative action, busing, and other failed attempts to “force” integration.

Unraveling the Enigma

I think Robin is correct that many of Thomas’s views about race and racism are often hiding in plain sight; people hear — or don’t hear — Thomas in highly selective ways.

For me the real enigma of Thomas is that his beliefs can be refracted through so many prisms simultaneously. For Robin he can become the conservative Black nationalist for whom race is everything and who harbors an apocalyptic vision of America’s future. For prominent liberal and left-leaning legal scholars like the late A. Leon Higginbotham and Randall Kennedy — who did a brutal take-down of Thomas in his review of Robin’s biography in The Nation — Thomas is the ultimate sell-out, vapid, cruel and antagonistic toward the Black freedom struggle that accounts for the objective conditions of his own success.

For conservative scholars Thomas is a talented and long-suffering hero, “courageously” facing down his detractors, decade after decade, as a conservative thinker who just happens to be Black. Indeed, Ralph A. Rossum, author of Understanding Clarence Thomas: The Jurisprudence of Constitutional Restoration, argues that Thomas’s race actually worked against his nomination to the Supreme Court.

Not surprisingly, Rossum locates the key to Thomas’s judicial philosophy in his embrace of color-blindness, the values of the Declaration of Independence, and what he views as the restoration of the original general meaning of the framers of the Constitution.

Reading Rossum and Robin side by side is like day and night. Both question the view of Thomas as the silent justice, who rarely speaks during oral arguments before the Court because he is not intellectually capable and suitably qualified. Rossum notes that Thomas has written “more than 475 majority, concurring, and dissenting opinions,” and “penned scores of law review articles and speeches.”

Rossum takes great pains to demonstrate that Thomas was in fact, in George Bush’s words, the “best qualified” person for the position on the high court. (1) Robin for his part notes that the only other Justice who has had his intellect and qualifications so relentlessly questioned was Thurgood Marshall, which should give critics pause at least on this score.

Yet the two books are diametrically opposed when it comes to judicial interpretation. In case after case and opinion after opinion, Robin argues, Thomas has been devoted to a battle to undo the grand experiments wrought by the civil rights movement and the Warren Court, experiments in integration and social welfare of which he believes himself to be a victim, along with the rest of Black America.

Thomas’s jurisprudence, as Robin summarizes it, “begins with the belief that racism is permanent, the state is ineffective, and politics is feeble, and ends with a dystopia that looks painfully familiar: men are armed to the teeth, people locked up in jails, money ruling all, and racial conflict as far as the eye can see.” (219)

In this interpretation, Thomas sees race everywhere and often uses the history of racism to justify his opinions. Because the federal government has acted in racist ways in the past, the logic goes that it ought not be empowered to act in the future.

Strictly curtailing the power of federal government, which has long been the goal of the conservative movement, is also, Robin asserts, part of Thomas’s pro-adversity strategy. Only under conditions that are harsh and brutal can the Black community “develop its inner virtue and resolve.” What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.

“It’s astonishing how openly Thomas embraces not just federalism but a view of federalism associated with the slaveocracy and Jim Crow,” Robins writes. Read through a very different prism, this defense of federalism is fairly close to what Rossum calls Thomas’s philosophy of original general meaning.

“I have said in my opinions that when interpreting the Constitution justice should seek the original understanding of the provision’s text, if that text’s meaning is not readily apparent,” Rossum quotes Thomas, explaining that the original understanding of the Constitution also incorporates what both “the delegates of the Philadelphia and of the state ratifying conventions understood it to mean.” (13)

“Originalism” and Judicial Philosophy

In both Rossum’s and Robin’s attempts at translation and interpretation, Thomas wants to return us to the beginning.

For Rossum, Thomas’s faithful adherence to the original general meaning of the Constitution — ideally a fixed meaning that doesn’t change — is said to provide him with a source of judicial restraint and a dedication to impartiality. It functions as a bright line that finds an action consistent or inconsistent with the Constitution, and allows us to scrape away “the excrescence of misguided precedent” in order to restore “the contours of the Constitution as it was generally understood by those who ratified and framed it.” (23)

Part of this scraping can involve an adversarial view toward precedents (think Warren Court rulings), expressed as both a refusal to apply them and an open invitation for future cases to overturn them.

What might look like a form of rightwing judicial activism is not, for Rossum, because this philosophy aims to restore the Constitution to its original meaning. It is a form of judicial restoration. Above all, Rossum affirms, this doctrine ought to prevent us from “infusing the constitutional fabric with our own political views.” (30)

This does not mean, however, that one cannot have a judicial philosophy; Rossum located Thomas’s in both an originalist interpretation of the Constitution, but also in the Declaration of Independence that forms its “higher law background.” Although it precedes the Constitution and is not therefore legally binding, the Declaration provides the best defense, in Thomas’s words, “of limited government, of the separation of powers, and of the judicial restraint that flows from the commitment to limited government.” (Quoted, 20)

The Declaration is also the font of the fundamental principle of equality said to inform the Constitution, and for Rossum that equality — that “all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights” — is both individualistic and absolutely color-blind.

Being blind to color demands at the same time a kind of blindness to power. As Rossum puts it: “As far as the Constitution is concerned, it is irrelevant whether a government’s racial classifications are drawn by those who wish to oppress a race or by those who have a sincere desire to help those thought to be disadvantaged.”

Race and Rights

Although both books cover a good deal of legal and Constitutional ground, especially Rossum’s, both return time and again to questions of race and the prospects for African-American advancement in Justice Thomas’s America.

Rossum shies away from too much biographical detail in accounting for his subject’s views but does note that one reason for Thomas’s attraction to the Declaration of Independence’s higher law traditions is the question of slavery.

His interest in the Declaration, Thomas writes, “started with the . . . simple question, How do we end slavery?” and after having done so, “by what theory do you protect the right of someone who was a former slave or someone like my grandfather, for example, to enjoy the fruits of his or her labor?” (Quoted, 19)

Here again is the source of individual rights over group rights, personal responsibility and hard work in order to overcome histories of oppression and discrimination. Rossum also uses the “what he learned from his grandfather” lens to stress Thomas’s rejection of paternalism and notions of Black inferiority “on which paternalism is based.” (189)

Because Blacks are not inferior, there is no need, for example, for “forced integration” in schools just to be near “superior” white students; no need to regard “racial imbalance” or “racial isolation” as a Constitutional problem in need of remedy in voting rights cases; no need for affirmative action, only “a need for equitable remedies for those individuals who have experienced discrimination.” (190)

In this instance Rossum and Robin arrive at roughly the same destination, having taken dramatically different highways. Both scholars also make use of Justice John Marshall Harlan’s famous dissent in the Plessy v, Ferguson decision that justified legal segregation based on race. Harlan wrote:

“Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows or tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved.”

Rossum sees this as basis for Thomas’s decisions on issues such as affirmative action (Thomas quotes Harlan in his opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger, for example) and as part of Thomas’s dedication to restoring the original meaning of the Constitution by sweeping away wrong-headed precedents.

Robin also uses Harlan, but quotes from the line before the famous articulation of color-blindness:

“The white race deems itself to be the dominate race in this country. And so it is in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty.”

In other words, color-blindness, as Robin is quick to observe, can sit side by side of a racially unequal society, and can constitute a form of racism without explicit reference to race.

Robin puts aside all the conservative “boilerplate” decisions that Thomas has penned; Rossum is what you get when you add them all back into the mix. Rossum approaches Thomas without all of the biographical messiness, content with a few observations such as Thomas’s affection for his grandfather and a reading of his Black Nationalism that simply (and for Robin, falsely) notes that “Meanwhile, his militancy dwindled, and his opposition to affirmative action grew.” (40)

Robin, on the other hand, wants to make the invisible Justice visible by arguing that few Justices have made their biographies so central to their jurisprudence. For Robin, the ideas that Thomas developed about the Constitution were deeply informed by his understanding of race and gender as well as by his disillusionment with the Black freedom struggle. Rossum is not so burdened.

Voting Rights Gutted

Rossum’s Thomas is a love letter to the conservative movement that was determined to gut and overturn the civil rights revolution, especially in and around voting rights. Like Robin, he gives ample time and space to Thomas’s opinions in landmark cases such as Holder v. Hall, the 1994 case that began the gutting of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that has been all-but-completed by the majority ruling in Shelby County v. Holder (2013).

In the former case, Thomas denounced the use of remedies to ensure the collective influence of Black voters and to fight against the dilution of Black voting power, insisting that such matters were outside of the original purview of the Voting Rights Act and therefore an improper subject for the court to review.

Further, Thomas denounced the collectivist assumptions lurking behind the claim of Black voting strength and Black voting dilution as a paternalistic insult and as a form of “apartheid.”

Rossum traces this back to Thomas’s adherence to the color-blindness of the Constitution; Robin roots it in Thomas’s belief that African Americans can never find their collective interest satisfied or addressed through the electoral process, a racially rigged game in which whites will always call the shots.

Both interpretations leave us in the same dismal swamp, gussied up as progress in Shelby County v. Holder, 19 years later. Writing for the 5-4 majority, Chief Justice John Roberts held that blanket federal protections once guaranteed under the Voting Rights Act are no longer necessary to prohibit racial discrimination in voting because, “our country has changed.”

Justice Ginsberg countered that this is like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” Thomas sided with the majority. (For an excellent overview of the implications of this decision, see “How Shelby County v. Holder Broke America,” Atlantic Monthly, July 10, 2018).

What Went Wrong?

For understanding how we got from here to there and the decisive role played by Thomas in the transformation of the Court, both books reward the efforts of the reader. Reading them together is a strong reminder of just how partisan and ideological this transformation has been.

They also both offer a vision in which the Constitution is no longer the sword (Robin) or the crutch (Rossum) to reform the social, political and economic order.

In both instances we’ve come a long way from Wilson J. Moses’s Golden Age of Black Nationalism, which is not necessarily a bad thing. But Robin offers a far more profound challenge for political radicals to find and occupy spaces of disagreements with Thomas’s underlying vision, which so many of us have come to share, a vision, Robin argues, “of the permanence and autonomy of race, of the inability of politics to overcome social disrepair, of the ineffectiveness of state action.”

For Robin, the question in the end, may not be to ask where Thomas went wrong, “but where we did.” (221)

This is a ravishingly clever analysis that unexpectedly closes the political divide between Thomas and disaffected leftists. But this startling conclusion leaves a few loose strings, two of which strike me as especially pressing. The first threads across just how well Robin captures the elliptical nuances of Thomas’s approach to race, society and the U. S. Constitution, and whether he is overly selective in his interpretation of Thomas’s body of work.

Of course, Rossum is equally selective is his own ideologically-laden way, and surely Thomas is more than a jurist with his own particular spin on “original intent” interpretations of the Constitution. Yet in some ways Rossum gives us a more comprehensive overview of Thomas’s voluminous writing.

The second loose string coils around Robin’s use of Black Nationalism as a trans-historical intellectual tradition and as a set of contemporary political affiliations. Has he taken too many liberties here?

Even at its most conservative, Black Nationalism has never yet been stretched so far as to encompass positions articulated in Robin’s version of Thomas. Decades ago Moses demonstrated the ideological flexibility of Black Nationalism, but herein Robin leaves it so contorted as to be unrecognizable.

I suspect that relative to this issue, among others, Clarence Thomas will remain an enigma for years to come.

July-August 2020, ATC 207