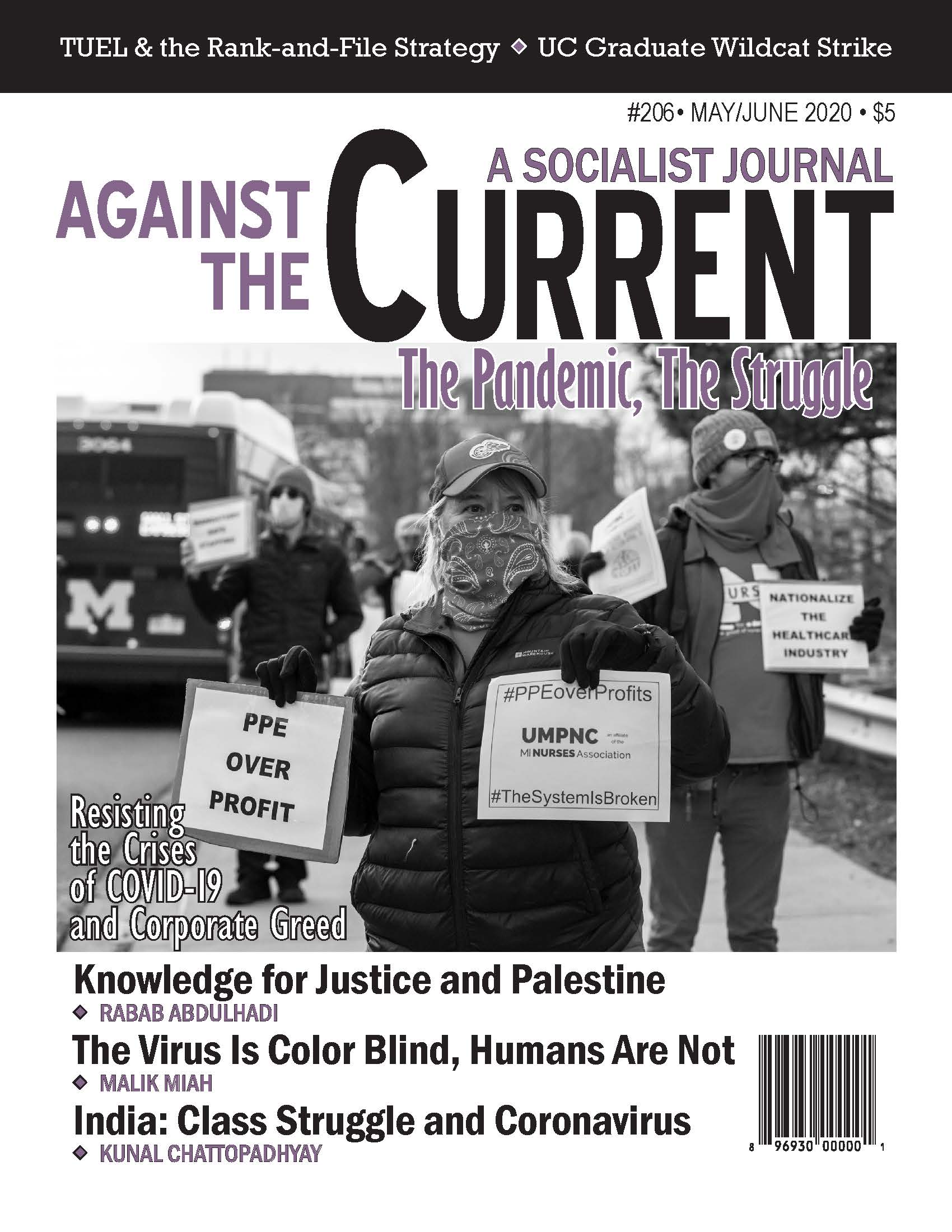

Against the Current, No. 206, May/June 2020

-

A Crisis of Vast Unknowns

— The Editors -

Virus Is Color Blind, Not Humans

— Malik Miah -

UC Graduate Student Workers Wildcat Strike

— Shannon Ikebe -

Two-Tier Response to COVID-19

— Ivan Drury -

Producing Knowledge for Justice

— Rabab Abdulhadi -

On the Delhi Pogrom

— Radical Socialist, India -

Class Struggle and the Pandemic

— Kunal Chattopadhyay -

Introduction to William Z. Foster and the TUEL

— The ATC Editors -

TUEL and the Rank-and-File Strategy

— Avery Wear -

A New Economy Envisioned?

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

A Bitter Class Grudge War

— Rosemary Feurer -

The GI Bill, Then and Now

— Steve Early -

Vagabonds of the Cold War

— John Woodford -

A Problematic Diagnosis

— Michael Tee -

Hidden Deaths in a Long War

— Barry Sheppard -

Hugo Blanco's Revolutionary Life

— Joanne Rappaport -

Karl Marx in His Times

— Michael Principe -

Karl Marx in His Times

— Michael Principe - In Memoriam

-

Gene Francis Warren Jr., 1941-2019

— Ron Warren -

Socialism as a Craft

— Mike Davis

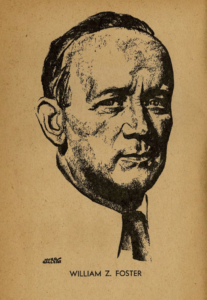

Avery Wear

BY THE END of the strike-happy decade of the 1910s, the small U.S. syndicalist movement led by William Z. Foster pushed the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to the threshold of mass industrial unionization in the Packinghouse and Steel campaigns. Yet the culmination of Foster’s remarkable efforts at revolutionizing the labor movement were still to come.

The Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), like the Syndicalist League of North America (SLNA) before it, sought to organize labor’s “militant minority” into an alternative leadership to that of the conservative “labor fakers.”

But where the abortive SLNA had merely shown promise, the TUEL over several years rallied mass forces in multiple unions for heroic struggles with varying outcomes. It was the most significant concerted left intervention in established U.S. unions to date.

It is a history ripe for study 100 years later, as a reborn socialist movement debates its labor strategy. But its achievements stand out fully only when one takes account of the exceptionally unfavorable circumstances facing labor in the 1920s.

The end of World War I brought mass unemployment, persecution of radicals, and a conservative political turn. Employers responded to the wave of labor militancy that had peaked in 1919, with the Open Shop Drive.

Over the next decade union membership fell from five to two million members, as union leaders moved toward class collaboration to save their organizations and positions. The space for alliances of AFL leftists with progressives against conservatives steadily closed.

Where a radical figure like Foster could find a place alongside Chicago Federation of Labor leader John Fitzpatick, and even Samuel Gompers himself, in the Steel campaign in 1918-19, he would soon find himself isolated and attacked.

Foster’s Conversion and Early Successes

The defeat of the Great Steel Strike left Foster famous and well-connected but without steady work or an organizational base. Opposed to “socialist politicians” since leaving the Socialist Party for the IWW in 1909, he was amazed to find the most powerful of allies in one such figure: Lenin.

Lenin’s pamphlet “Left Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder” argued what Foster had long said against overwhelming left-wing opinion: revolutionaries must forsake IWW-style dual unionism to fight for the masses in the AFL unions, no matter how conservative their leaders.

After attending the founding Congress of the Red International of Labor Unions (RILU) in Moscow (1921), Foster secretly joined the Communist Party. He brought with him the TUEL, formed earlier in 1921. The TUEL had appeared stillborn until the influence of Lenin’s pamphlet and Foster’s conversion to Communism.

Like the SLNA, the TUEL worked against any appearance of dual unionism. There were no dues. Membership depended on subscribing to its newspaper, The Labor Herald.

TUEL’s program called for union transformation by amalgamating craft into industrial organizations, union democratization via shop by shop self-representation (the “shop delegate system”), class struggle not class collaboration, anti-racism, rejection of the two capitalist parties in favor of a labor party, recognition of Soviet Russia, and affiliation with RILU.

With his previous connections and the Party’s national collection of branches, Foster in “rapid fire” fashion (said James P. Cannon) produced TUEL branches in 90 cities.(1) Through frequent national, regional and industry conferences, the TUEL organized to fight at the level of both the union locals and the national/international organizations.

At Foster’s insistence it maintained independence from the Party, and future CP head Earl Browder claimed in 1922 that 90% of League members were not in the Party.(2)

The TUEL immediately launched nationwide campaigns for amalgamation and a labor party. It sent ballots to 35,000 union locals querying support for a labor party. Seven thousand mailed back “yes.” The TUEL’s leading branch, in the Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL), obtained the support of that body for a Labor Party.

The CFL also approved the League’s resolution calling on the AFL to hold a national conference to begin amalgamating craft unions into industrials. TUEL branches obtained endorsement of this from 17 State Federations, scores of municipal labor councils, and thousands of locals. Fourteen Internationals endorsed as well.(3)

AFL President Samuel Gompers feared an unprecedented clamor for a general strike. “United front” strategy, in which the TUEL sought to ally with progressive union leaders like Fitzpatrick and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Sidney Hillman, showed dramatic potential just as they had during the Steel and Packinghouse campaigns.

The campaign for amalgamation advanced furthest under the TUEL’s Railroad Department. Sixteen craft unions divided up railroad workers; 400,000 struck together across five of them in 1922, while the rest kept working. The TUEL denounced this scabbing. Foster went on a national speaking tour, “gaining a foothold” among the railroad workers.(4)

Over 3000 railroad Locals endorsed the League’s detailed plan for amalgamation. With the defeat of the strike, frustration that could have led toward dissolution instead channeled toward the organized left wing.

The International Association of Machinists (IAM) had members affected by the sellout of the railroad strike as well. The TUEL’s opposition to the strike settlement, in which unions agreed to labor-management cooperation on unfavorable terms, combined with amalgamation proposals in a potent appeal to the rank and file.

At the 1924 IAM Convention, five Locals moved the amalgamation proposal. This was defeated. But in the union’s March 1925 Presidential election, the TUEL backed progressive Vice President J.F. Anderson, after significant totals for their own independent candidates in the primaries.

President William Johnston (himself a Right-wing Socialist) barely survived in a 50-vote victory, likely only through fraud. (Opposition to the League in the IAM was fueled in part by their uncompromising demand to organize Black workers. Samuel Gompers forced the union to drop their formal Constitutional ban on Black membership in 1895, but allowed the ban to continue in practice.)

Bureaucracy and Sectarianism

But the nationwide backlash had already begun. The AFL viciously red-baited Foster and the League. Many unions expelled members. And they collaborated with the Federal Justice Department to identify, fire and even prosecute them.

Historian Philp Foner rightly emphasizes this. In addition, the defeat of the railroad and miners’ strikes in 1922 ended the last gasp of postwar militancy.

But crucially also, bureaucratic meddling from the degenerating Communist International began. Foner fails to deal forthrightly with this. In 1923 the Moscow-apppointed U.S. Communist International representative John Pepper (alias of Hungarian Joseph Pogany) demanded that the Party press for an immediate Labor Party Presidential campaign — despite Foster’s warnings that pushing ahead was premature and would alienate Fitzpatrick’s CFL.

It was “impossible for the (Communist) party by itself to lead the rank and file revolt to establish the Labor Party,” Foster said. His warnings came true. Fitzpatrick — who was also pressured by Gompers’ threats to cut off AFL funding — withdrew CFL support for amalgamation, the Labor Party, and anything “supported by Foster and his friends.”(5)

The Hillman alliance soured as well. Labor’s conservative mood in the ‘20s would certainly have been inhospitable for the further development of the left-progressive united front. But it did not have to lead to the disaster of total isolation for the TUEL by 1925.

The previously boundless promising united front opportunities foreclosed abruptly. Foster’s career from the 1912 founding of the SLNA to this point had racked up powerful demonstrations of the potential for left initiatives to move organized labor forward. It made the most of the united front opportunities of the late Progressive era.

There are similarities with today’s climate in unions. For more than two decades, labor’s declining membership and clout have fed a reformist malaise at the top.

A train of events including John Sweeney’s New Voices leadership, ambitious organizing in the service sector, the Fight for 15, and experimentation with social justice unionism have created a climate in which many union locals have a far less closed atmosphere than in earlier decades. Anti-communism has waned considerably, and the question of how to revive the movement is open for debate.

Evolving Strategy and Facing Repression

But there was more to the TUEL than reliance on the temporary openness of the minority progressive wing of the labor bureaucracy. After 1923 the TUEL came to rely solely on independent organization and rank and file support to survive.

Fortunately, this type of support is not as ephemeral. Moving away from electioneering and “endlessly passing resolutions” (which while demonstrating widespread support for left proposals, had proven “futile” as means for advancing concrete change6), the League’s most dramatic mobilizations happened despite the period’s heavy persecution.

In the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), future progressive President John L. Lewis desperately tried to ram though weak agreements and concessions to a coal industry determined to survive economic crisis by attacking its workforce. Lewis and his violent thug regime expelled rebellious locals and militant leaders like Alexander Howat after several postwar wildcat strikes. But the spirit of rank-and-file revolt survived in spite or because of the defeat of the 1922 strike, providing the basis for a TUEL presence. Openly Communist miner George Vozey got 31% of the 1924 UMWA Presidential vote, despite fraud and intimidation.

When the industry forced the reluctant Lewis into another strike in 1927, the TUEL’s “Save the Union” committee called for all-out measures. When the Lewis machine failed to organize nonunion miners or provide adequate relief to strikers, Save the Union organized these actions on their own.

They championed Black members’ rights, gaining widespread support in Pennsylvania. One Black miner said at the 1928 conference of Save the Union that it was the first time in 25 years that he was allowed to speak at a Union meeting.

Communist Party branches began to proliferate in mining towns. As the national strike spiraled toward defeat, the committee called out the Union’s northeastern district without Lewis’ approval, in a heroic attempt to shore up a failing cause. The ensuing disaster not only wrecked the committee, it nearly destroyed the UMWA — which dropped from 600,000 to at most 150,000 members.

The general picture was similar in the needle trades. Wartime wildcat strike waves had cohered left-wing opposition caucuses. Pro-Soviet radicals expressed widespread sympathies in these East European immigrant milieux.

Meanwhile the moderate socialists who led these unions, some wielding corrupt gangster shock troops, sought to impose austerity on the ranks in order to avoid direct confrontation with a cost-cutting industry.

In the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), TUEL slates won top offices in several Locals, including three in New York City. In response ILGWU President Morris Sigman expelled those Locals, cutting off funds for offices and salaries. The Locals in turn organized greater rank-and-file involvement, effectively keeping the Locals flourishing despite the attempted death-blow. In 1925 a humiliated Sigman re-admitted the Locals.

The TUEL won elections to lead Locals of the Millinery workers in Boston, Chicago and New York. They proposed to a recalcitrant national organization that they organize the women workers, who would otherwise undercut union men’s wages. The left-led locals then proceeded to carry out this plan on their own resources, with considerable success.

In New York’s Local 43, 400 initial members in 1924 became 4,000 by 1926. An 18-year old TUEL member, Gladys Schechter became known as the “Joan of Arc of the Millinery Workers” for leading this, the largest Local of women workers in the country at the time.

Union-sponsored mob violence against women picketers, union recruitment of scabs against its own members, and expulsions of TUEL members eventually cleansed the League from the union.

TUEL influence in the ILGWU ended after the defeat of a strike it led in 1926. Historian Edward Johanningsmeier claims that the Communist Party factional struggle between Foster and Charles Ruthenburg meant that Foster was afraid to accept a necessary compromise deal with the employers, for fear of being charged with a sellout by Party rivals.

Expulsions also drove the TUEL from the IAM, railroad unions, and the Carpenters. But in the International Fur Workers’ Union (IFWU), the TUEL overcame all obstacles.

Ben Gold, left-wing socialist and leader of the wartime opposition “Furrier’s Agitation Committee,” campaigned for member-organized picket lines. This was against the IFWU’s practice of hiring gangsters for picket duty, to counter the employers’ picket-bashing mobsters.

The failure to heed Gold contributed to a disastrous defeat in the strike of 1920, decimating the Union. But the remaining 600 (out of 10,000 previous) members rallied to Gold’s rank-and-file committee, now under the auspices of the League.

President Kaufman lost control of the New York Local, but maintained leadership of the IFWU. He used that position to undemocratically stack Conventions, wage mobster terrorism, and expel Gold. But the New York Local refused to break under bureaucratic pressure.

Gold won election back to Union office. He ordered an audit to uncover corruption. Gangsters threatened him with guns, but rank-and-file Furriers outnumbered and drove them out. The League launched an organizing drive among Greek workers, who had been the main scabs in 1920.

In 1926 thousands of newly unionized Greeks won a rare 1920s victory in sweeping fashion, winning a very unusual early 40-hour week, increasing pay, and banning unpaid overtime. (The Local had organized Greeks in part by fighting overtime abuse using direct action, shop by shop.)

Ben Gold soon displaced Kaufman as IFWU President. The Union thereafter became a pioneering stronghold of militant, democratic and social justice unionism, including by extending consistent and crucial support to Black civil rights struggles over a period of decades.

What Was New in the TUEL?

Prior to the TUEL the great majority of U.S. labor leftists practiced and supported dual unionism, primarily in the IWW. The influence of the early Comintern flipped the script, putting Foster and “boring from within” at the head of the mainstream of ’20s labor leftism.

Unlike the SLNA, the TUEL eschewed dogmatic decentralization. League chapters coordinated and challenged union bureaucracies at the national as well as the local level.

Under Foster’s influence the League continued the SLNA tradition of autonomy from political parties, something that was important to its broad alliances early on. But this autonomy was steadily sacrificed under pressure from rival Party factions and Moscow.

Kim Moody correctly criticized the Party’s sectarian identification with the League,(7) but it is worth remembering that a rather opposite approach with correspondingly positive results had happened early on in the League.

Later the TUEL evolved toward greater reliance on independent rank-and-file self-activity, from organizing drives to member-run union offices to direct workplace action. The theory of unions is that they belong to the members. Acting consistently on this principle can disarm conservative attacks and bring the unique power of the working class to stop production more readily into the frame.

Comintern leadership, based in a Russian revolutionary experience in which unions, as opposed to workers’ councils, had played little role, had little to say about this. But worker Comintern leaders with roots in the wartime Scottish Shop Stewards movement had already theorized the TUEL’s later approach, according to Darlington.(8)

The Stewards, operating inside large and established factory unions, participated in and linked up mass workplace assemblies that organized antiwar strikes and solidarity with neighborhood tenants’ struggles.

The assemblies consisted of rank-and-file union members acting independently of the unions. They were the equivalent, in their limited geographic area of Glasgow, of the Russian soviets or workers’ councils.

Steward and later Comintern delegate J.T. Murphy saw unions as necessary media for the assemblies to emerge from, even as the assemblies transcended (without necessarily directly conflicting with) the unions. He argued that traditional left strategies aimed at taking over official union office inevitably tended toward conservatization because unions are inherently sectional, aimed at coexistence with capitalism, and require a bureaucratic layer of staffing and leadership.

This led Murphy to argue for the long-term priority of independent rank-and-file organization. Though experience caused the TUEL to grope toward similar conclusions, there is no evidence that Murphy’s thinking influenced it.

The TUEL showed that an independently organized militant minority allows socialists to merge with masses of workers inside unions, without dropping or hiding their politics. In fact, those politics if intelligently applied can allow that organized minority to provide alternative leadership.

The combination of union leadership sluggishness and member alienation often produces a vacuum of vision and ambition, a vacuum waiting to be filled.

Independent rank-and-file groups, and individuals where necessary, can propose joint action when and where progressive leaders are receptive, while at all times building and relying on rank-and-file involvement. Resolutions and electioneering can very usefully gauge, demonstrate and cohere support for socialist strategies. But rank-and-file self-activity tends to be necessary for concrete gains.

In periods of labor retreat the environment may become hostile and repressive for radicals. But the TUEL experience shows that organizations in crisis are not only the most in need of saving, they can also be the most ripe for radical changes of direction.

Notes

- Cannon, James P., “William Z. Foster: an Appraisal of the Man and his Career” 1954/56/58. Available online at https://www.marxists.org/archive/cannon/works/1954/foster.htm.

back to text - Barrett, James R., William Z. Foster and the Tragedy of American Radicalism, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1999, 134.

back to text - Foner, Philip S., History of the Labor Movement in the United States, vol. 9, The T.U.E.L. to The End of the Gompers Era, International Publishers, New York, 1991, 155.

back to text - Johanningsmeier, Edward P., Forging American Communism: the Life of William Z. Foster, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1994, 183.

back to text - Ibid., 202.

back to text - Ibid., 219.

back to text - Moody, Kim, “The Rank-and-File Strategy: Building a Socialist Movement in the U.S,” 2000. Available online at https://solidarity-us.org/rankandfilestrategy/.

back to text - Darlington, Ralph, Radical Unionism: the Rise and Fall of Revolutionary Syndicalism, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2008. See especially Chapter 8, “Union Bureaucracy.”

back to text

May-June 2020, ATC 206