Against the Current, No. 204, January/February 2020

-

Hope in the Streets, continued

— The Editors -

On the Coup in Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Canada's 2019 Election

— Paul Kellogg - Students in Pakistan

-

Introduction to H. Chandler Davis

— Alan Wald -

Speaking Up in Ann Arbor

— H. Chandler Davis -

Beyond the 2019 UAW Negotiations

— Dianne Feeley -

100 Years of U.S. Communism

— Alan Wald -

Introduction to Socialist Perspectives on the 2020 Elections

— The Editors -

Socialists and the 2020 Election

— Linda Thompson and Steve Bloom - Black History

-

How Race Made the Opioid Crisis

— Donna Murch -

The Pursuit of Truth in the Delta

— Paul Ortiz -

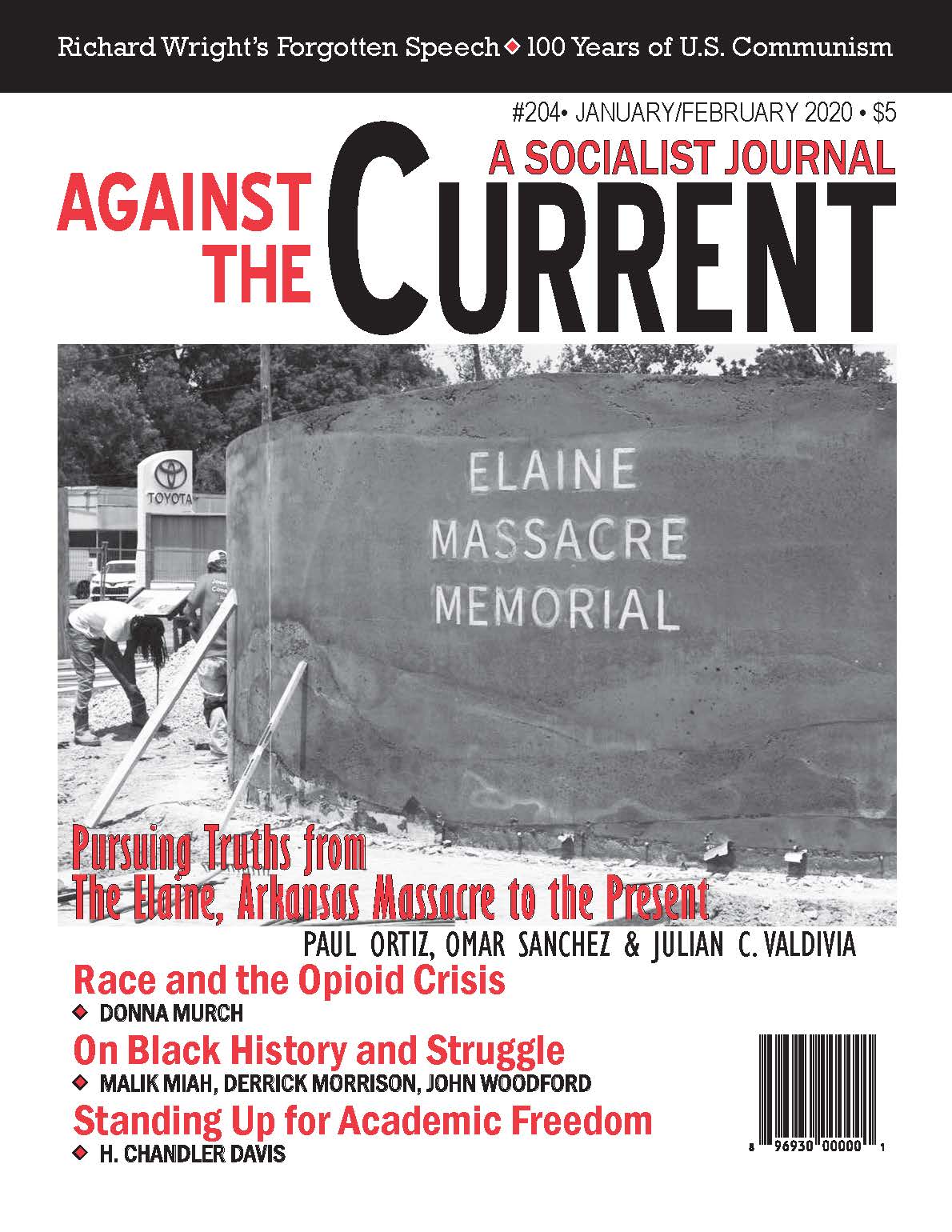

1919 Elaine Massacre

— Paul Ortiz -

Discrimination in the Delta

— Julian C. Valdivia -

A Freedom Odyssey

— Omar Sanchez -

Introduction to Richard Wright's Forgotten Speech

— Scott McLemee -

Such Is Our Challenge

— Richard Wright -

"Not racist" vs. "Antiracist"

— Malik Miah -

A Chronicle of Struggle

— Derrick Morrison -

Justice Denied

— John Woodford - Reviews

-

Latin America's Caldron

— Folko Mueller -

Syria's Unfinished Revolution

— Ashley Smith -

The Power of Gulf Capitalism

— Kit Wainer -

Lawyers of the Left

— Barry Sheppard

H. Chandler Davis

LET ME MAKE a case for urgency of defense of academic freedom.

I’m not addressing the whole University community. Surely there are some who don’t have any concern for academic freedom as the AAUP (American Association of University Professors — ed.) understands it. Some who think, for example, that it was honorable and right in 1954 that the President of the University at that time fired Mark Nickerson and myself for perceived disloyalty.

Certainly I want to engage those people in debate, but that is not what I’m about here. I’m addressing friends, the majority that values the protection and encouragement of variety of opinion within the scholarly community: President Mark Schlissel, most of the faculty, most students.

Also, my plea is not directed at those who insist that the policies of the government of Israel be immune to criticism. I do engage those rigid Zionists in debate, quite a lot, it’s important to do so; but that’s not what I’m doing now.

I’m assuming here that the free exchange of ideas we value in academe includes candor on Palestine. Let’s take for granted that it is legitimate on campus to call a crime a crime even if the victims are Palestinians.

One can say in the halls of the United Nations that it is unethical to hold under military control all the lands Israel occupied in 1967; to introduce large numbers of new settlers in the territories and enfranchise them but not the original population; to hold two million people, mostly already refugees, in the Gaza Strip in conditions essentially of imprisonment.

To condemn these Israeli practices is not only tolerated in the international forum, it is the prevailing opinion. It is a debatable opinion; indeed, Benny Morris, who is a leader among the historians who have uncovered the facts of the ethnic cleansing of Palestine 1947-1949, supports the practice!

The present article is directed to those — again, I think I’m addressing the majority — who see how wrong Israeli state policy is. Some of you may be uncomfortable with terms like “Israeli apartheid,” but let’s not get hung up on a few such words: Israel gives one ethnic group favored status, and enforces its overlordship with overwhelming weaponry, and if you don’t want to call that apartheid, call it what you will.

How Do We Respond?

I hope we can agree also that recognizing the atrocity leads legitimately to looking for ways to combat it. Most of us look for non-violent ways. This is not cowering before armed might, even the nuclear weapon (which Israel has never promised not to use); nor is it necessarily committing to any philosophy of passive resistance.

Most Palestinians resist non-violently too, as in demonstrations in villages like Nabi Salih — or even the Great March of Return, where hundreds of Gazans week after week expose themselves to merciless wounding: though a few may use slingshots against the heavily armed IDF (Israeli Defense Force), they do not inflict serious casualties and do not aspire to.

Accepting the policy of non-violence limits one to tactics like boycotts, and this is what many Palestinians and their supporters call for. Since 2005 or even longer, the world has been urged by leaders like Omar Barghouti to subject Israel to Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) until justice is won.

This is not a recipe for action. Supporters differ on what actions are called for. I support the BDS campaign, but I wish I could avoid giving the impression that we are boycotting Israelis like journalists Amira Hass and Gideon Levy, not to mention valued friends like Professors Emmanuel Farjoun and Gadi Algazi, people whose contribution to justice in Palestine I can only admire and can’t emulate.

Some of those Israelis (Jewish and Arab), under the name Boycott from Within, collaborate with the international BDS movement in efforts to end support for Israeli policies and institutions. But some do not: some Israeli academics active in the difficult resistance I’m talking about dislike the call to boycott.

You understand that I am not engaging those who disagree with the objectives of BDS. As I have said, just now I am talking to friends. Let us assume agreement that for example, we should try to restrain the settlers from destroying hundreds of Palestinians’ olive trees.

Those of us who don’t go in person with the International Solidarity Movement to conduct civil disobedience, in the tradition of Rachel Corrie, cast about for actions we can meaningfully take from this distance. We do disagree, and regularly explore tactics among ourselves.

For example, years ago I happily accepted invitations to visiting positions at Israeli universities; yet today I urge young colleagues to consider declining such offers on principle. Some of us would refuse to recommend a student to a study program at an Israeli university; yet all of us protested when the Palestinian-American student Lara Alqasem was (for a time) denied permission to enter the country to study at Hebrew University.

Cultural contacts across borders can be precious peace-makers; yet most of us urged (for example) the Toronto Raptors to decline an invitation to celebrate in Israel their NBA championship.

Such questions of choice of tactics must be assayed seriously, as Omar Barghouti and all our allies must appreciate. Weighing alternative methods of action does not mean resigning ourselves to inaction.

It’s very different when some among us are attacked for standing up for Palestinian rights. John Cheney-Lippold and Lucy Peterson at the University of Michigan were denounced not for their choice of means — refusing to recommend students for study in Israel — but for their objectives.

Steven Salaita was victimized at the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana not for bad choice of words in e-mail against the IDF’s shelling of Gaza, but for objecting to the shelling of Gaza at all. Actually I never saw his messages, just as I never heard what programs the students of Cheney-Lippold and Peterson had applied to in Israel.

It is not required that we endorse every action and every utterance of colleagues in order for us to defend their freedom. Let us clear the air by insisting on this distinction. Taking away Steven Salaita’s tenured appointment was unjust; denying Norman Finkelstein tenure at DePaul as punishment for his views on Palestine was unjust; any penalties on Cheney-Lippold and Peterson for their adherence to the BDS campaign are unjust.

We can debate calmly among ourselves what tools to use in defending Palestinian rights; but we must unite to defeat the powers that would silence the defense.

Echoes of 1950s Purges?

Now am I saying that the attempts today to purge the universities of supporters of Palestinian rights are like the purge of the 1950s? Be patient while I compare them, having seen both.

The number of firings from American Universities for perceived communism in the great Red-hunt of 1947-1960 was in the hundreds, and the firings for perceived adherence to BDS or the like today are much fewer.

There is one effect that looks very similar. In the 1950s any untenured academic might be leery of signing a petition critical of the United States fighting a war in Korea (to take one example), knowing it would be vulnerable to public attack. The same went for critical examination of the capitalist system.

In the present period, criticism of the Israeli treatment of the Palestinians is subject to the same chill. We all know perfectly well that if you want to criticize the occupation of the West Bank you had better reflect on your job security, because Canary Mission [a website that blacklists pro-Palestinian student activists, professor and organizations —ed.] is watching you.

So what? We go right ahead, only we watch our step: what’s wrong with that? Let me try to shoot down this complacency.

In the first place, constantly guarded speech is not free speech. It doesn’t do the job free speech is needed for, the exploration of ideas and values. Capitalism was due for more re-evaluation, and after the silence of the Red-hunt descended it took a long slow struggle to get it back on the agenda.

Likewise, if we agree that the ethnic cleansing of Palestine needs exposure and condemnation, then we must fight for the right to discuss it freely.

In the second place, let me caution the beginning academic. If you have a few years to go to tenure, and you’re treading carefully all that while, there’s a risk you may end up imitating the uncritical conformists so successfully that there’s no difference — especially since even tenure doesn’t really give you security if Alan Dershowitz and Cary Nelson come hunting your scalp. Pussyfooting is not free-wheeling; defend your freedom.

In the third place, and this is too often overlooked, firing is not the main punishment held over your head. If you speak up for Gaza’s access to clean drinking water, or if you quarrel with the IHRA’s so-called “working definition of anti-Semitism,” you will quite likely not be fired forthwith; but even if you are not, you will be put on the list, and when you go up for your next job, you will have opposition from the start. Powerful opposition, open or covert.

This is called the blacklist. It really hurts. Here I am, wanting the coming generation to take heart and speak up, but I have to tell you that it may really cost you.

All right, this purge is less thorough than the one I fell to; many jobs have been saved. Joseph Massad kept his position at Columbia after a fight, and David Klein at Cal State Northridge, and Rabab Abdulhadi at San Francisco State. No firings so far at University of Michigan, either.

Some of the targets suffered penalties and threats of further penalties, however, but I’m drawing attention to something else: when you go looking for your next position, you’ll be up against the same barrier that has kept Steven Salaita and Norman Finkelstein out of academe in the USA since they lost their jobs.

Fighting Back As a Community

Young university teacher, if the consequences of letting yourself be known as pro-Palestinian give you pause, you are not being paranoid. Face it. And everyone, face it.

Don’t accept it. Recognize that there’s a blacklist in operation, that it is stifling free speech in an important area of policy. There must be something we can do about it, right?

I’m not talking about the victims. I moved to a job I really liked in another country; most blacklistees did not fare that well. But I’m not talking about individual safe havens, I’m pleading with you to deal with the problem as a community.

One thing I learned over the years is that the purge feels very different if it manages only to almost exclude someone. When I job-hunted after 1954, I got zero university offers in my field; later when my friend Ed Dubinsky job-hunted, he got just one. Now one is very close to zero, it’s as close as nine is to eight, yet having one good offer allowed Ed to return to a satisfying life of teaching and scientific work.

The purge had almost worked in his case, yet the sting was pulled. But look what that means. That means that most of the force of Canary Mission’s onslaught is overcome if just one employer finds the courage to step up and break the wall of exclusion for each targeted job-seeker.

That means, in turn, that the blacklist presents its ominous solid wall only by the collaboration of all employers in a field. The blacklist is everybody rejecting you.

As a consequence, the guilt is every employer’s. Every university that won’t hire a dissenter is an accomplice in the crime of deterring the next generation’s free dissent. It is fair — and this is the moment to do it — to demand of every American university: don’t be an accomplice. Break the unanimity. Offer a professorship to Steven Salaita. Offer a professorship to Norman Finkelstein.

January-February 2020, ATC 204