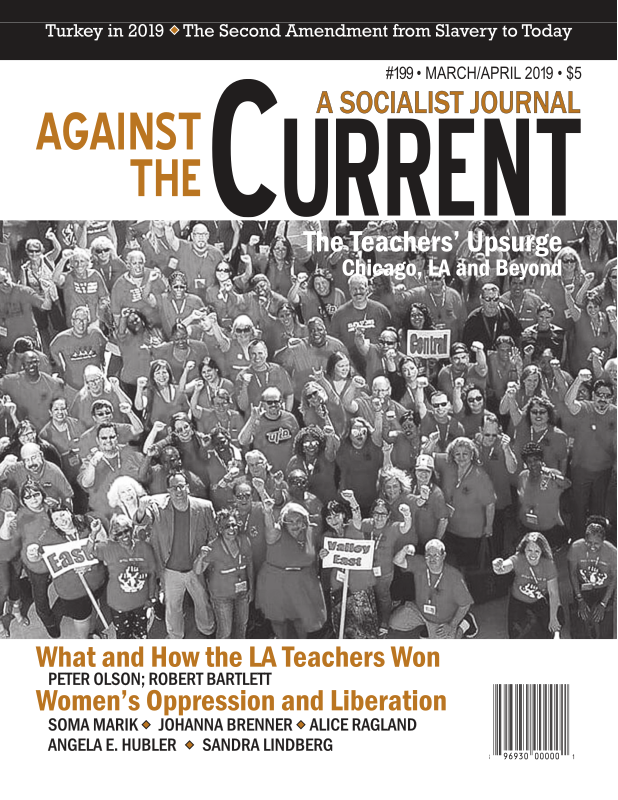

Against the Current, No. 199, March/April 2019

-

Whose "Security" -- and for What?

— The Editors -

MLK in Memphis, 1968

— Malik Miah -

California Burning, PG&E Bankrupt

— Barri Boone -

PG&E Bankruptcy

— Barri Boone -

What Los Angeles Teachers Won

— Peter Olson -

The UTLA Victory in Context

— Robert Bartlett -

Chicago Charter Teachers Strike, Win

— Robert Bartlett -

Turkey in 2019: An Assessment

— Yaşar Boran -

Betraying the Kurds

— David Finkel -

The Strange Career of the Second Amendment, Part II

— Jennifer Jopp -

Who Is Responsible?

— David Finkel -

A Note of Thanks

— The Editors - Socialist Feminism Today

-

Women's Oppression and Liberation

— Soma Marik -

Marx for Today: A Socialist-Feminist Reading

— Johanna Brenner -

Angela Davis: Relevant as Ever After Thirty Years

— Alice Ragland -

The Activism of Angela Davis

— David Finkel -

White Women and White Power

— Angela E. Hubler -

Lots of Scurrying But No Revolution in Sight

— Sandra Lindberg - Reviews

-

A Call to Action

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Orbán: Strong Man, Authoritarian Ideology

— Victor Nehéz -

A Sympathetic Critical Study

— Peter Solenberger -

Further Reading on the Russian Revolution

— Peter Solenberger

Victor Nehéz

Orbán — Hungary’s Strongman

By Paul Lendvai

Oxford University Press, 2017, 224 pages, $28.45 hardcover.

PAUL LENDVAI’S STUDY Orbán — Hungary’s Strongman won the prestigous European Book Prize for 2018, earning him €10,000. His book was originally published in Hungarian and, because Viktor Orbán is a really extraordinary personality in European politics, is now available in English. At the moment Orbán is serving his third consecutive term as prime minister (2010, 2014, 2018). Assuming his government lasts its full term, he will become the longest-serving Hungarian prime minister in history.

The author is a Hungarian-born Austrian journalist who fled to Vienna after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution ended with the Soviet invasion. He was the Vienna-based correspondent for the Financial Times for 22 years and a columnist for the major Austrian daily newspaper, Der Standard.

The book begins by quoting philosophers who draw varying conclusions about the dynamic relationship between the individual and history. This leads into the author’s discussion of the most popular and successful East European politician of the 20th century, the Communist János Kádár, who served a 32-year term. Lendvai calls him “a dictator without personal dictatorial tendencies.”

After Kádár together with Soviet troops repressed the revolution and arrested, tried, found guilty and executed 229 people — jailing thousands more — it was clear who was in charge. But this was followed by a raise in the living standards and the gradual introduction of small freedoms such as the possibility of going abroad (first to Soviet bloc countries, later to capitalist countries as well.)

The Kádár regime offered both security and a chance for individual prosperity. All the regimes afterward — including Orbáns’ — could not offer that. Today a child born into poverty has little chance to alter this condition. Most will die in the same circumstances in which they were born.

The Hungarian regime with its one-party system, and under the thumb of the USSR, had stigmatized the 1956 uprising as a counter-revolution. The day of historical reckoning with the taboos of the Soviet era came on June 16, 1989 in Budapest’s Heroes Square during the reburial of Imre Nagy and other martyrs of the 1956 revolution. At this rally only six people spoke. The speech most remembered for its clarity and conciseness was that by an unknown 26-year-old, Viktor Orbán. He openly demanded that Soviet troops withdraw.

Orbán’s Beginnings

The original Hungarian title of the book, New Conquest, refers not only to how someone from a simple rural background was able to step forward but also — as we can read in the first three chapters — how he utilized his 15-20 former university friends to gain and maintain his status. They first came together through their political activities in the students’ union at István Bibó Special College for law students. (Bibó was a opposition political philosopher who founded the college in 1983.)

According to Lendvai, Orbán’s political career should be examined together with his colleagues because of their incredible group history. Together with some oligarchs from the new national capitalist class, this grouping built a powerful political party, Fidesz (Alliance of Young Democrats).

In spite of a few splits and changes, this handful of former students have remained at the helm of their party for 30 years. They have protected their group identity and seized total power over a whole country.

Preparing for Power

Early in Orbán’s political career Lendvai interviewed him frequently. His book traces Orbán’s parlimentary rise after the regime change in 1990 and details how he moved Fidesz from being a liberal student organization to a center-right party. He also reveals Orbán analyzing the mistakes of the first freely elected prime minister, the conservative Jozef Antall.

Orbán was critical of Antall for failing to build up a media campaign and an economic base capable of sustaining a rightwing government. Thus, Orbán was already thinking about techniques to build and sustain his own political machine.

Thanks to the neoliberal decisions and widespread corruption of the so-called Socialist-Free Democrats’ government (1994-98), Viktor Orbán and his party won the 1998 election; he became the second youngest prime minister of Hungary. (The author incorrectly identifies him the youngest one; actually the youngest was a Stalinist politician, András Hegedüs.)

Lendvai doesn’t mention it, but Orbán used his office to support the consolidating power of the Hungarian upper class. However Orbán’s extremely aggressive tone toward the opposition and his nationalist attitude cost him the election four years later.

Yet his defeat did not teach Orbán that gratuitously antagonistic confrontation was unhelpful. Lendvai comments, “On the contrary, he maintained he had not been sufficiently adept and nowhere near tough enough in his managing of the government.” Over the ensuing eight years he prepared himself for his second chance.

The author paints a fairly positive assessment of the Socialist-Free Democrats’ coalition government first led by a technocrat banker, Péter Medgyessy. Yet the author does criticize Medgyessy for his “distribution of electoral goodies,” which increased the budget deficit.

Lendvai can’t deny his own mainstream (neo)liberal values, and consequently is not ready to examine the first welfare program of the post-Communist era from the viewpoint of the unprivileged. Instead he allows neoliberal pundits to express his opinion.

Nor does the author realize how this neoliberal point of view frustrated ordinary people. Orbán, however, proved skilled at appealing to these frustrated citizens and offering a dream that captures the loyalty of majority.

Lendvai details how the world economic crisis hit Hungary and how rampant corruption and the divisive personality of the following prime minister, Ferenc Gyurcsány (who thought himself a Hungarian Tony Blair), led to Orbán’s comeback victory in 2010.

From the moment he took his oath of office as prime minister, he saw the opportunity the constitutional majority provided. As Lendvai explains, Orbán immediately moved to “turn this into an impregnable fortress of power.”

This is true not only in legislation passed, but in developing political symbols for the regime. At the early stage, Orbán called it a System of National Cooperation. The pompous text, a “Manifesto of National Cooperation,” was hung in a 20 X 27 inch glass frame in all public offices.

In conjunction with accepting the New Constitution as the New Fundamental Law of Hungary, each local mayor established a table of this New Fundamental Law in the office so that citizens could study this granite-stiff document — as he used to call the paper. Since 2011 the document has been modified seven times.

The “Mafia State”

To analyze the nature of the regime Lendvai uses a popular expression, Mafia State, coined by a liberal minister, Bálint Magyar. As Lendvai says, “the Mafia State is a privatized form of a parasite state, an economic undertaking run by the family of the Godfather, exploiting the political and public instruments of power.”

He notes that some analysts emphasize the “systematic demolition of the fundamental institutions of democracy,” while others call it “a hybrid regime in which the features of the authoritarian system are stronger than those of democracy.” Orbán for his part likes to call it “illiberal democracy.”

Lendvai provides a detailed explanation of the major steps by which Orbán liquidated the government’s system of checks and balances. He cites with delight Orbán’s egregious ambition and well-formulated plan by quoting him: “I make no secret of the fact that in this respect I would like to tie the hands of the next government. And not only the next one, but the next ten governments.”

Now serving his third consecutive term, Orbán’s motto is: “We have only to win once, but then properly.”

In power Orbán was no longer willing to be interviewed, even by Paul Lendvai. While once they seemed to have a genial relationship, since Orbán and his party formed the government in 2010 neither Lendvai, nor the decreasing numbers of the opposition media, have that possibility.

Orbán’s handlers will do anything to prevent a journalist from interviewing the prime minister. It was only when Orbán was in Brussels that, adapting to the local policy, he was forced to speak with journalists.

The author demonstrates how Orbán dominated the media in 2015 when the migrant crisis unfolded as they merely sought passage through Hungary. He unleashed a giant hatred campaign, building on fear and anxiety among the Hungarian people.

He stated: “We do not want to be diverse and … we do not want our own colour, traditions and national culture to be mixed with those of others.” He encouraged people to develop an obsessive fear of those who wanted to walk through the country to the West. He wanted them to avoid looking at the refugees’ sorrowful condition and offering to help.

In Lendvai’s opinion the only threat to Orbán’s hold on the country can come from civil organizations. That’s why Orbán strives to depict them as the paid agents of the Hungarian-born George Soros.

Soros has all the necessary qualities to be perceived as the perfect enemy: a multibillionaire who lives in the West, who is Jewish, seen as an outsider, and someone who supports migrants. For Orbán, Soros, Brussels, the West and migrants are all enemies.

Lendvai concludes that the success of the Orbán regime comes from the weakness of the opposition, which he sees as untalented, in the government’s pocket or inept. While there is some truth in that analysis, it is a superficial explanation. It doesn’t explain Orbán’s skillful dealings.

Stabilizing the economy is central to Orbán’s rule. And it is true that the opposition parties are associated with the earlier, more chaotic economy.

How German Capital Aids Orbán

In fact Orbán’s success is not only because of a deeply divided opposition but the fact that after the great recession he was able to stabilize the economy using the resources of the European Union. His economic decisions flawlessly satisfied the interests of Western capital, first and foremost those of the German auto industry.

If the leaders of the German conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its Bavarian twin party the Christian Social Union (CSU) would slap Orbán’s hand, Orbán and his party would walk out of the European People’s Party in the European Parliament.

Orbán would then fall back into his real place. But the chance for this is tiny, because leaders of the German automotive industry love doing business with him.

With Orbán in charge, parliament operates as a huge factory, passing new bills at a rapid pace. There are new bills on elections, on the media, and on all institutions that could be possible checks and balances.

Although the author properly presents how Orbán cleverly makes sure all posts are filled with his commissars, he fails to notice how changing the Labor Code has strengthened the interests of capital.

Strike action is restricted. The introduction of a flat 15% income tax lets the rich off the hook, while the corporate tax rate of 9% transforms Hungary into a tax-haven.

Orbán does much to veil the fact that he eats from the hands of German establishment, and claims his government is independent. And because he has seen to it that there aren’t strong unions, he makes Hungary cosy for capital.

Thanks to weak labor regulation and the ridiculously low level of taxation, Western companies operating in Hungary make extra profits. Combining this strategy along with his partnering of local oligarchs, Orbán has state money to create jobs and presumably keep citizens happy so they don’t worry about the withering of democratic institutions.

We can see the same utilitarian logic — not mentioned by Lendvai — in relation to the Paks nuclear power plant. Initially the European Commission raised objection to its extension by Rosatom, the Russian state nuclear power holding company, because there had been no transparent bidding process. But when it turned out that the most expensive part of the new power plant will be delivered by Alstom, a French company, and the U.S. General Electric corporation, the criticism disappeared.

We can see that the interests of the West coincide with the authoritarian capitalism of the Orbán regime. This enlarges the picture of Orbánism. Its political-economical interest finds favor with local and international big business alike. This reality, in turn, relays an alarming and disturbing message to ordinary people who might be allies in helping to defend us and overcome the precarious world order.

What a pity that Paul Lendvai’s book doesn’t provide that larger story.

March-April 2019, ATC 199