Against the Current, No. 197, November/December 2018

-

Supreme Toxicity -- Confirmed

— The Editors -

The Constitutional Root of Racism

— Malik Miah -

Trump and Science

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Europe's Political Turmoil (Part I)

— Peter Drucker -

Ecosocialism or Climate Death

— Ecology Commision of the Fourth International - Realities of Labor

-

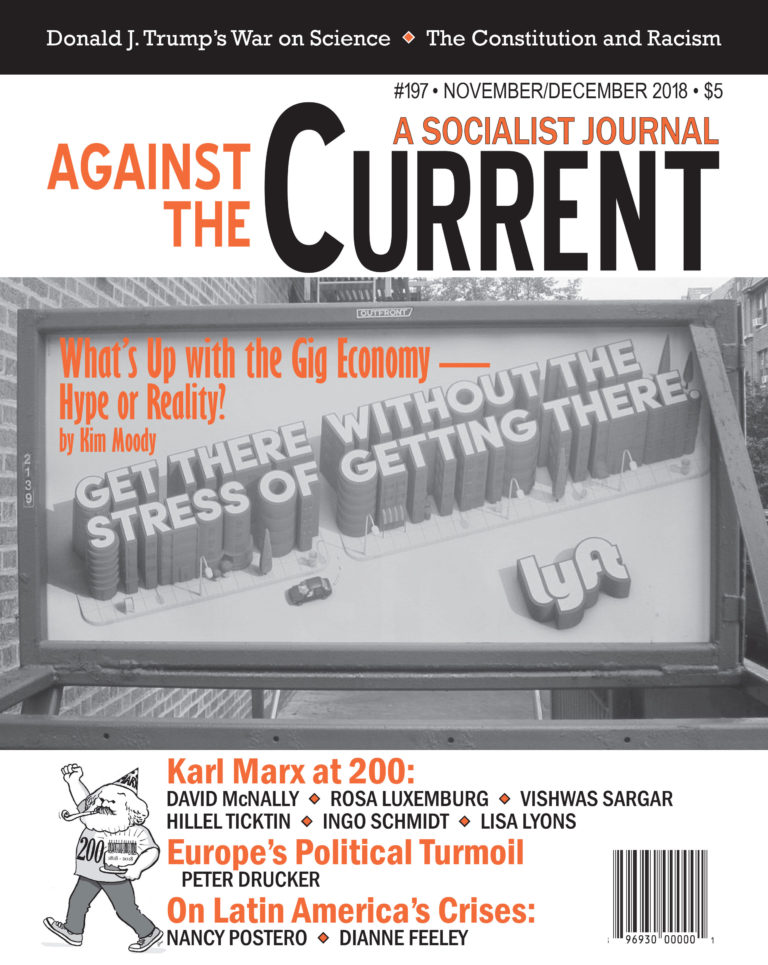

Is There a Gig Economy?

— Kim Moody - Karl Marx at 200

-

Karl Marx: Revolutionary Heretic

— David McNally -

Marxist Theory and the Proletariat

— Rosa Luxemburg -

Marx and the "International"

— Vishwas Satgar -

Karl Marx in the 21st Century

— Hillel Ticktin -

Marx's Capital as Organizing Tool

— Ingo Schmidt - A Century Ago

-

The End of "The Great War"

— Allen Ruff -

Triumph and Tragedy

— William Smaldone - Reviews

-

The Making of Corporate Empire

— Jane Slaughter -

The Saga of a City Rising

— Michael J. Friedman -

Slavery and Capitalism

— Dick J. Reavis -

The Logic of Human Survival

— Barry Sheppard -

Architects of Mass Slaughter

— Malik Miah -

Two Powerful Films on Indonesian Mass Terror

— Malik Miah -

The Wars of Rich Resources

— Nancy Postero -

Latin America Crises and Contradictions

— Dianne Feeley - In Memoriam

-

Jan and Carrol Cox, Political Activists

— Corey Mattison

Malik Miah

I’VE BEEN ASKED many times, “What is institutional racism and when did it originate?” I generally respond with a litany of facts about Black unemployment (twice that of whites), housing discrimination (redlining and higher mortgage costs), Jim Crow-type de facto segregation (public education is worst in African-American communities), military and job discrimination (skilled jobs and tech openings).

Yet my answer is still incomplete. The source of institutional racism is rooted in the U.S. Constitution itself.

It is easy to argue that I’m being ahistorical. Look at the progress, even with the zigs and zags. Aren’t African Americans better off, even if their net wealth is only a fraction of white people’s?

Let’s look at how institutional racism was consciously incorporated in the language of the Constitution.

Original Documents

By the late 1700s the slave trade was on the decline, considered immoral by many educated and enlightened politicians in the United States and Europe. Slavery and racism, however, were powerful economic advantages for increasing property owners’ wealth. U.S. capitalist development was built on the enslavement of Africans, benefitting Northern and Southern farmers and traders.

While the Constitution never used the words “slavery” or “slaves,” the document did include provisions defending that inhumane institution.

Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 allocated Congressional representation based “on the whole Number of free Persons” and “three fifths of all other Persons.” Articles IV and V, and the 12th Amendment (the last added to the Constitution nearly 80 years after the signing of the original document), also addressed the issues of slavery, slave rights and the slave trade without using the words.

The Founding Fathers knew that race and racism lay at the economic base of the new country. The decision to give enhanced political power to the slavocracy was based on a common view held by whites that Africans were inferior to European whites.

Northern delegates were opposed to chattel slavery, but freely accepted counting slaves as three-fifths of a human to give the slavocracy more representatives in the new Congress. The concepts of federalism and state rights were thus fully tied to slavery, race and racism.

States’ Rights for White Supremacy

From 1800 to the 1860s and the crushing defeat of the pro-slavery Confederacy, laws adopted by Congress and rulings of the Supreme Court upheld slavery and racial discrimination. The presidents all supported or accepted the racist ideology.

President Lincoln and the new Republican Party openly opposed slavery and supported its abolition. Although Lincoln was careful in his words because of white racism in the country, the Radical Republicans were for immediate abolition.

There were no civil rights acts adopted before the Civil War. Since then there have been eight laws or amendments to the Constitution for civil rights. Why so many?

States could limit or block the laws under the Constitution’s state rights protections — labeled as Federalism. The federal government has mainly accommodated the states.

The most important way to allow freedom of choice is the right to vote without restrictions. The United States is the only major bourgeois democratic country that does not have a national voting rights standard. States’ rights protection is the source of that denial.

The first post-Civil War civil rights act was the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished chattel (human) slavery — a great victory for humanity. But it left it up to the states to implement what happens to the freed people. It included the notorious phrase, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” (my emphasis)

What happened next was that former slaveholders sought to bring back de facto slavery. They pushed laws that limited freedom. Freed slaves never received land (a major demand). The right to vote was limited. Freed slaves never received a way to sustain themselves on their own.

Mass incarceration is an ironic byproduct of the exception phrase in the 13th Amendment. Some 20 percent of Black males today cannot vote because of prison records.

Civil Rights Laws

The first empowering Civil Rights Act, adopted by Congress in 1866, guaranteed the rights of all citizens to make and enforce contracts and to purchase, sell or lease property.

The 14th Amendment was adopted by Congress in 1868 and ratified by the states in 1870. It was written to include and protect the rights of freed slaves. It declared that all persons born or naturalized in the U.S. were citizens, and that any state that denied or abridged the voting right of males over the age of 21 would be subject to proportional reductions in its representation in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The 15th Amendment was adopted in 1869. It forbade any state to deprive a citizen of his vote because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

The Reconstruction Civil Rights Acts were adopted in 1870, 1871 (two) and 1875 to enforce the new amendments that nullified sections of the original Constitution.

Among other things, these acts placed all elections in both the North and South under federal control; barred discrimination in public accommodations and on public conveyances on land and water; prohibited exclusion of African Americans from jury duty; and banned discrimination in voter registration on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

They established penalties for interfering with a person’s right to vote. That gave federal courts the power to enforce the act and to employ the use of federal marshals and the army to uphold it.

From Counterrevolution to Modern Civil Rights

The counterrevolution began soon after federal troops left the South. It included using extralegal terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan to successfully end the possibility of Black equality.

By the late 1880s, the door was shut. Southern states passed “Black Codes” to deny Black rights and dignity, later codified as Jim Crow segregation laws.

It took 75 years to get the next Civil Rights Act in 1957. Seven years later President Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. It came after the March on Washington in 1963 and the growing power of the movement.

In 1965 the modern Voting Rights Act was adopted with teeth. In 1968 a law against housing discrimination was adopted by Congress.

Blacks began to shift from the Republican Party in the 1960s. Those who could vote had once identified with Lincoln’s party, not the pro-segregation Democrats. The alliance between northern Democrats and southern Dixiecrats kept the issue of civil rights off the agenda, until the power of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s forced a shift by the Democratic Party leadership who saw urban Blacks as a new voting bloc.

It led African Americans in droves to join the Democratic Party — thousands are now elected officials — and white southerners to leave and change the corporate Republican Party in the 1970s.

Key Lessons

What does this history explain about institutional racism and the role of the U.S. Constitution? Race was key in all decisions by the ruling class (liberals and conservatives) — that is, to maintain white supremacy and Black inferiority.

Although amendments are possible that remove or mitigate the worst features of the Constitution, those amendments can be nullified in practice, and the original language still remains.

It’s time to review the power of states over basic human rights that affect every citizen and resident.

Voting and civil rights should be based on common standards nationwide, where states can make them stronger but never weaker. Fundamental change requires extralegal mass action directed at the institutions and governing parties of the state.

The U.S. Constitution is where institutional racism was encoded from its origins. It’s time to tell the truth and stop the uncritical celebration that rationalizes the glacial — and always reversible — march toward equality.

November-December 2018, ATC 197