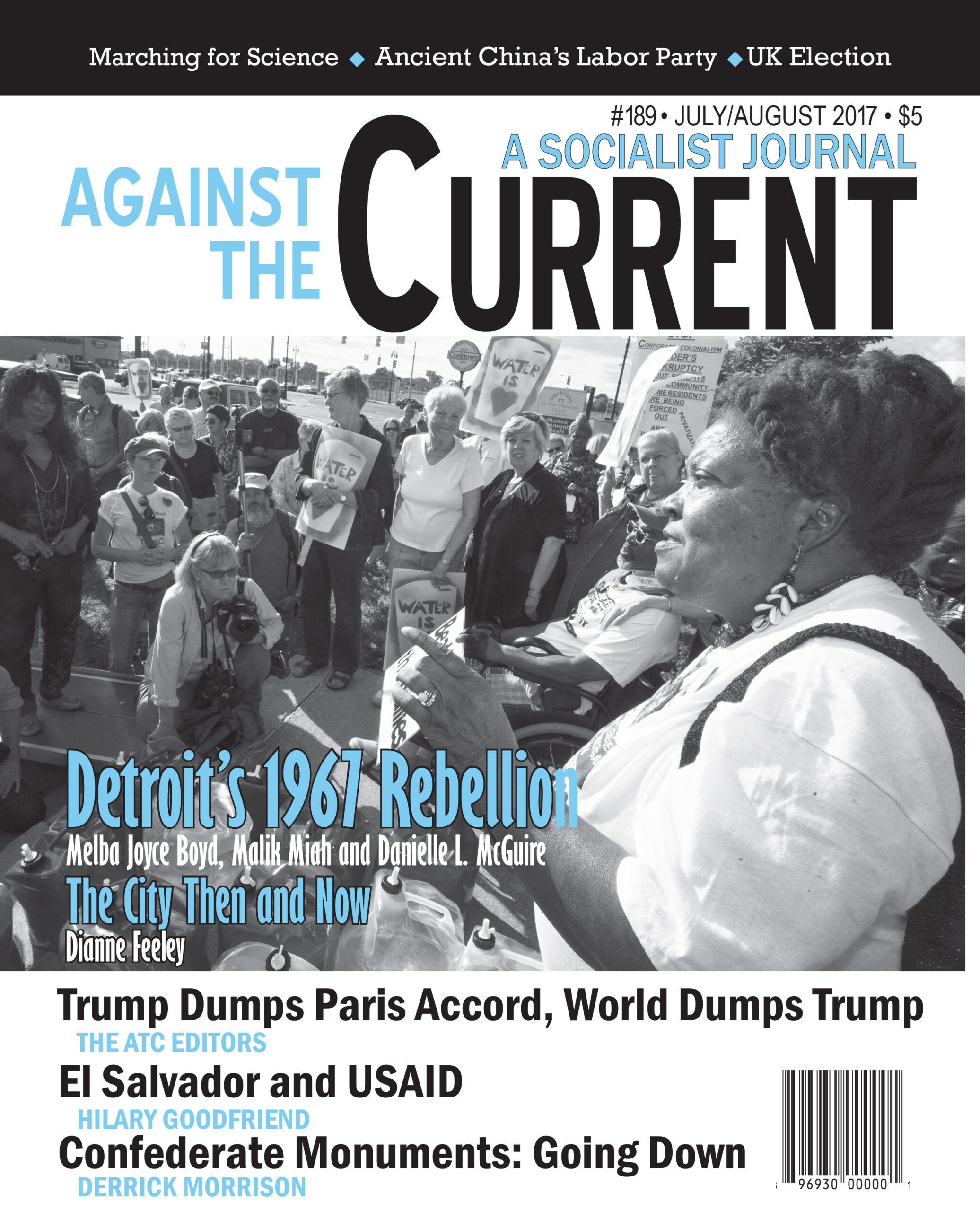

Against the Current, No. 189, July/August 2017

-

The Longest Occupation

— The Editors -

One-Half Cheer for Trump?

— The Editors -

Marching for Science and Humanity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

California Science Marches

— Claudette Begin -

Confederate Monuments Down

— Derrick Morrison -

Theresa May's Katrina

— Sheila Cohen and Kim Moody -

USAID in El Salvador: The Politics of Prevention

— Hilary Goodfriend -

China's Ancient Labor Party

— Au Loong-yu - Sweatshop Shoes for Ivanka

- Fifty Years Ago

-

Detroit's Rebellion at Fifty

— Malik Miah -

Roots of the Rebellion

— Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd -

Murder at the Algiers Motel

— Danielle L. McGuire -

A Tale of Two Detroits

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Birth of the "Open Shop"

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Teachers as Change Agents

— Marian Swerdlow -

The World and Its Particulars

— Luke Pretz -

The Unraveling Middle East

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The World Through African Eyes

— Anne Namatsi Lutomia -

Poland's Solidarity and Its Fate

— Tom Junes -

The Russian Revolution: Workers in Power

— Peter Solenberger

Tom Junes

Seeing Through the Eyes of the Polish Revolution:

Solidarity and the Struggle against Communism in Poland

By Jack Bloom

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014, 428 pages, $28 paperback.

IN 1980, HUNDREDS of thousands of workers challenged the foundations of the communist regime in Poland and won the right to form an independent self-governing trade union. It was an unseen first in the Soviet bloc, and these events played their part in precipitating the demise of communism in Poland and elsewhere in the bloc.

There have been many journalistic accounts and academic studies of the rise of Solidarity in Poland, which poses the question whether another book could bring something new to the relatively vast amount of literature on the topic. In this respect, Jack Bloom’s book certainly stands out in bringing the story of Solidarity to the English-language reader through an impressive set of interviews and first-hand accounts.

As the author explains, the book focuses “on the experiences and perceptions of the people who participated in these events as presented through their voices, as they explain here what they saw happen around them, the role they played, and how they understood these events.” (3)

Using material from 150 interviews he conducted with workers, opposition activists, party and even security apparatus functionaries, he has reconstructed the history of Solidarity in an easily readable and richly narrated way. Travelling to Poland in 1986 with only a handful of initial leads, Bloom found that his scholarly expertise on the U.S. civil rights movement opened doors that led him into the heart of the Polish democratic and workers’ struggle.

A System in Crisis

Bloom starts with mapping the structural context of the communist regime in Poland. Instead of outlining a totalitarian framework he underlines the networks of patronage developed under the nomenklatura system of Communist Party rule — referring to a list of names of people deemed to be loyal and politically reliable, from which the privileged elite was constituted.

While the system engendered poverty, it initially did provide unseen opportunities for social mobility for certain segments of society. Once these opportunities decreased and disappeared over time, the communist system was left to operate through a deeply permeated logic of corrupt practices, which implicated the entire society and destroyed people’s sense of integrity and dignity.

It is this corrupt system of patronage that provides the overall framework for Bloom’s class-based analysis and approach to the history of Solidarity as a social movement. In the 17 subsequent chapters, logically arranged into three parts, the book recounts first the important events that constitute the prehistory of Solidarity, then focuses on “the sixteen months” of 1980-81 during which Solidarity operated legally, and finally moves through the decade of underground resistance to end with Solidarity’s resurgence and the fall of communism.

The second chapter traces elements of support for and resistance against the regime among the working class. Despite the repression of the Stalinist era, people were still hoping for a better life. It was also a time of large population transfers and internal migration.

The absence of any social cohesion in many communities inhibited resistance. Yet in cities and regions where working-class traditions had remained intact after the war due to a lack of “outsiders,” resistance to the regime was high. For this reason, for example in Silesia, outsiders were brought in and privileged by the regime over the native population, which was terrorised and discriminated against.

Nevertheless, in 1956 the working class in Pozna? rose up in an armed insurrection against the regime, which set in motion the first systemic crisis in communist Poland. The regime survived the crisis, but it had engendered change with a lasting impact. Importantly, the crisis also taught a valuable lesson — i.e. not to take up arms against the state, a form of struggle that could not be won.

The third and fourth chapters deal with the next systemic crises, those of 1968 and 1970, in which the generation that would make Solidarity was forged. Bloom tackles the student revolt of 1968, highlighting how the experience of repression and lies by the regime alienated the younger generation. He also notes that young workers joined the students who rioted against the regime, thereby going against a long-standing myth that workers were absent from the events of 1968.

In 1970, when workers rose up in revolt against price hikes, the regime responded with deadly violence. Bloom underlines how important this lesson would be for the rise of Solidarity. People never forgot the killings; there was hardly anybody who believed in the regime’s ideology; but most importantly workers had understood that they should not expose themselves to the state’s capacity to use violence. A decade later, the occupation strike would therefore be the preferred type of action.

Networks of Opposition

In the next chapters Bloom describes how the late 1970s provided a learning curve for various emerging networks of opposition. These networks started to flourish in particular after the relatively low level of repression — or more accurately the lack of deadly force — in the wake of a 1976 revolt.

Bloom stresses how opposition networks formed among the working class and in doing so revisits the “who done it” question that appeared in the literature in the first decade after the rise of Solidarity. He singles out two protagonists, namely the Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR) — largely leaving aside the various other oppositional initiatives and groupings that sprouted in this period — and the Catholic Church.

While acknowledging the importance of KOR, especially for providing “mind food” for the workers (131), Bloom stresses that the workers organised independently. Similarly, he points to the ambiguous role of the Church, which had a high level of penetration by the state’s security apparatus.

While the opposition was supported by a generation of militant priests who had come of age during the late 1960s, the Church’s hierarchy was rather looking out for its own interests. As such, the Church only had an indirect influence, significant at times — as when millions came out to see Pope John Paul II during his first visit to the country and Poles saw the potential strength of their numbers.

The next seven chapters are concerned with the events of the “Polish revolution,” the rise of Solidarity and its abrupt end with the December 1981 imposition of martial law. Bloom outlines how the strike wave started in the summer of 1980 and how workers on the Baltic coast managed to set up inter-factory strike committees.

Subsequently, he recounts how solidarity from farmers, students and artists played an important role in sustaining the strikes and how crucial it was that the miners and steelworkers in Silesia also initiated strikes. According to Bloom, it was the latter development that tipped the balance in the negotiations between workers and the regime.

In the ninth chapter the author reflects on the far-reaching transformative power of the revolution. As a result of the self-activity and empowerment of the workers, people started acting differently, leading to a moral regeneration of society.

The tenth chapter is devoted to reconstructing how Solidarity was formed from below and how the regime tried to counteract it. It details the conflicts of the first six months of Solidarity’s existence, when the movement was very much on the offensive.

Turning Point and Crackdown

In the eleventh chapter Bloom puts forward one of his key concepts — that of a “turning point.” He states that the so-called Bydgoszcz crisis was the turning point in the crisis of 1980-81, when Solidarity mobilized for a general strike but the leadership pulled back from the brink after securing some demands in marathon negotiations with the regime.

As a result, Solidarity was put on the defensive; a permanent rift appeared between moderates and radicals. Similarly, in the twelfth chapter, in what is probably his most significant analytical point, Bloom uses the concept of “political opportunity structure” to outline the constraints that Solidarity put on the party-state.

He underlines the role of youth and journalists, discusses the factional struggle in the party, and stresses the relationship between the party reformers and Solidarity. The failure of the reformers was crucial in pushing the party-state to a position of forceful resolution of the crisis.

The concluding chapter of the book’s second part describes how Solidarity was radicalized and society worn down by food shortages, hunger marches, rationing and a severe drop in the standard of living. Meanwhile the authorities gradually moved to prepare a crackdown.

On December 13, a military junta imposed martial law ending a protracted conflict between a radicalizing Solidarity and an intransigent party apparatus. The general public succumbed into a state of wariness.

The next two chapters present an account of a country under martial law and the repression suffered by workers and Solidarity activists. It discusses the initial ill-fated strikes against the military junta and provides testimony of the brutal crackdown with fatalities in two Silesian mines.

Bloom documents the various actions of resistance and discusses the Communist Party decline — a decline that would prove irreversible. The sixteenth chapter then addresses the question of how Solidarity managed to survive.

Bloom points to the younger generation of activists who kept the flame alive in small groups and to leading activists who had managed to escape and elude the martial law authorities, the importance of the underground press in giving people meaningful activity, and how street demonstrations were able to keep instilling some hope despite the hardships of underground life.

The subsequent chapter portrays a gloomy picture of wariness setting in among the remaining Solidarity activists until another “turning point” appeared: the murder of the militant Solidarity priest Jerzy Popie?uszko by secret police operatives.

The prosecution of the perpetrators demoralized the security apparatus and reinvigorated especially the younger generation, which wanted to act. Bloom also stresses the importance of new opposition initiatives, such as human rights groups and the Freedom and Peace Movement that emerged in the wake of the Popie?uszko murder and started acting in public at a time when Solidarity itself remained underground.

The final chapter discusses the communist regime and its demise. It points to how Solidarity re-emerged in the strike wave of 1988, which led to the Round Table talks and to semi-free elections in which Solidarity would emerge victorious.

Summing Up

While the more informed reader of Polish history would see many aspects of the book as rehashing known facts and presenting a familiar chronology, Bloom makes some important observations. He underlines the significance of previous crises as a learning process, and refreshes the narrative with the results of more recent research such as the fact that workers joined students in rioting in 1968 and that the 1976 revolt was larger than usually presented.

His use of oral history livens up the narrative, though in some cases more criticism could have been applied to some of his respondents. Leszek Maleszka is cited as a student and Solidarity activist, though he later turned out to be one of the most notorious secret police informers of the 1970s and 1980s, a fact which should have been known to the author by the time of publication.

In addition, some of the extracts from interviews cited seem to clash with the overall chronology. One weakness in Bloom’s account relates to the late 1980s in which he seems to avoid digging deeper into the resurgence of opposition.

There were a plethora of new grassroots movements carried by the younger generation, people who had not been affected by the repression and shock of martial law. It was in fact a younger generation of workers with no firsthand recollection of 1980-81 who initiated the strikes in 1988 and revived Solidarity.

Despite these few criticisms, Bloom’s book merits a place on a shelf of literature on Solidarity. He approaches Solidarity as a social movement through a class analysis. He also demonstrates that the movement was political from the outset, for instance organized according to regions (not crafts as would be more expected of a trade union). His conceptual use of the “turning point” is particularly useful to depict the moment when Solidarity started losing its momentum and rifts began opening that would have long-term consequences.

Bloom’s most important contribution is his application of the “political opportunity structure” to the state and how it was in fact constrained by the social movement. It would have been even more productive had he stressed this aspect more throughout the whole narrative. It provides a useful insight for scholars and activists alike: the success of a social movement largely depends upon the constraints and the “internal balance of forces” within the power structures it opposes.

The conclusion could have included more thoughts on the transition period and Solidarity’s legacy — particularly as its current-day embodiment is a right-wing conservative union supporting an increasingly authoritarian government. Bloom recognizes that the post-communist outcome is very different from the liberation envisioned by many of the movement’s pro-worker founders, but also that there is no turning back.

This reader regrets one missed opportunity: The author decided to remain within the Polish national framework. While he points out that workers were central (though not always the most important actors) to the Polish story of Solidarity and opposition to communism, this was not necessarily the case in other Soviet bloc countries.

All the more so, as Bloom wrote a seminal book Class, Race and the Civil Rights Movement, the story of Solidarity in Poland could have benefitted greatly from possible comparative insights based on the author’s expertise on the U.S. movement. In this way he might have expanded and pushed the debate concerning Solidarity in a very novel direction. (The latter is just an afterthought, a consideration in case the author is thinking of such a future project.)

In all, Bloom’s book provides the reader with a rich story told from the grassroots about one of the 20th century’s most important social movements. For this reason alone, the book is warmly recommended reading.

July-August 2017, ATC 189