Against the Current, No. 189, July/August 2017

-

The Longest Occupation

— The Editors -

One-Half Cheer for Trump?

— The Editors -

Marching for Science and Humanity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

California Science Marches

— Claudette Begin -

Confederate Monuments Down

— Derrick Morrison -

Theresa May's Katrina

— Sheila Cohen and Kim Moody -

USAID in El Salvador: The Politics of Prevention

— Hilary Goodfriend -

China's Ancient Labor Party

— Au Loong-yu - Sweatshop Shoes for Ivanka

- Fifty Years Ago

-

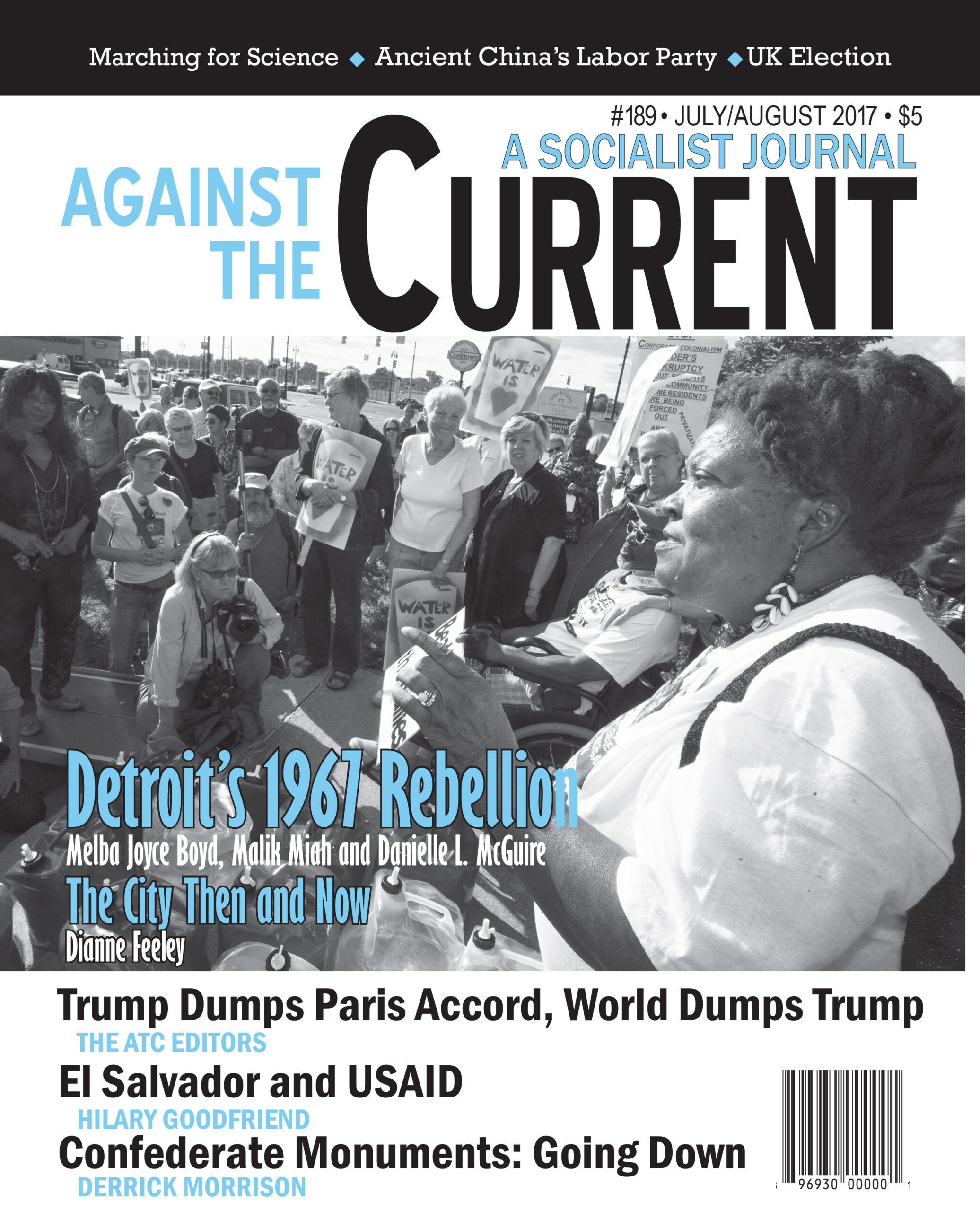

Detroit's Rebellion at Fifty

— Malik Miah -

Roots of the Rebellion

— Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd -

Murder at the Algiers Motel

— Danielle L. McGuire -

A Tale of Two Detroits

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Birth of the "Open Shop"

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Teachers as Change Agents

— Marian Swerdlow -

The World and Its Particulars

— Luke Pretz -

The Unraveling Middle East

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The World Through African Eyes

— Anne Namatsi Lutomia -

Poland's Solidarity and Its Fate

— Tom Junes -

The Russian Revolution: Workers in Power

— Peter Solenberger

Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd

For Against the Current’s discussion of the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Detroit rebellion, poet and cultural activist Kim L. Hunter interviewed Melba Joyce Boyd, Distinguished Professor in African American Studies at Wayne State University. Boyd She is an award-winning author of 13 books, nine of which are poetry. Her activism in a struggle against police abuse is referenced by Heather Ann Thompson in Whose Detroit? (Cornell University Press, 2004), 150.

Against the Current: Let’s talk about the language used to describe what happened in Detroit in July 1967, “riot” versus “rebellion.” People broke into stores and took things, pretty much at random and people consciously, intentionally set themselves up in buildings and shot at law enforcement. Over all, something pretty deep has to be happening when people set fire to hundreds of buildings. Both terms are being used with regards to the 50th anniversary.

Melba Joyce Boyd: I think you have to consider how it started, as the result of an altercation with the police. People started fighting back against the police. That’s a rebellion, not a riot. Sniping became bigger and bigger, spread to the point where the Detroit Police couldn’t quell it and, I suspect, were afraid to go in to certain parts of town and for good reason. The police knew they had been wrong, abusive.

The National Guard comes in; they can’t really put it down either. It’s not put down until President Johnson sends in the army. What’s significant about that is there were large numbers of African-American troops, and many snipers refused to shoot Black troops. That had a lot to do with why it stopped — it’s not talked about a lot, but I’m sure it was partly because many of the snipers were veterans.

Another question that comes up is, was it about race or class? I think initially it was about race. But then when you get into destruction of commercial property and it spreads into apartment buildings which, of course, most Black people don’t own, that’s tapping into deep rage and frustration — then I think it becomes a larger class issue.

The police repression issue crosses all classes for Black people. There was an incident with my stepfather recorded in the book Detroit 1967, Origins, Impacts, Legacies (Wayne State Press, 2017). In that book I talk about how pervasive police brutality was.

I relate the story of my stepfather who stopped the police once to report a traffic incident, to get them to write up a ticket. A white guy had rear-ended him on Schaefer in Southwest Detroit. The police showed up and told the white guy to go on, they’d handle it — and then grabbed my father and started beating him.

They ended taking him to the police station that used to be at Fort and Greene and put him in the basement and used him as a punching bag. He was charged with resisting arrest.

ATC: Assaulting an officer.

MJB: There you go. He goes to court, is convicted and doesn’t serve any time. I surmised that was because he had no record, was a college educated, gainfully employed, taxpaying citizen and a decorated war hero. The judge let him go, probably knew what happened because there were all these pictures of how messed he was.

That could happen to any Black person, not just somebody leaving an after hours joint on 12th Street. If you’re Black and the police decided they wanted to “do their thing,” you were vulnerable. There was no recourse. You go to court and you just have to hope for the best.

So when folks were rebelling against the police I mean, what else were they going to do? You can’t “tell” on the police.

ATC: Yes, your alternatives are virtually nonexistent.

MJB: Yes, they’re nonexistent. In pre-Coleman Young days, we didn’t have good options. So yes, I think it is a rebellion and “rioting” is an element of that. Anything else totally reduces what’s really going on. It was actually even more than Black people being fed up, it’s Black people fighting back. And if Johnson hadn’t brought in the Army, who knows?

ATC: When I talked with the late Ron Scott (a former Black Panther member and longtime community activist against police brutality) for the 30th Anniversary of the rebellion, he said there were really two “riots.” One was by the people, and the other by the police who were breaking into people’s homes, ransacking them ostensibly looking for weapons suspects, etcetera. He says the police riot didn’t stop until the troops showed up.

MJB: I guess you could call what the police were doing a riot, but that was just them doing what they did at the time, which also increased the sniping. The police would also go into apartment buildings and claim there were snipers, but they were just there to wreak havoc. When the police came to your house, there was nothing polite about it and I have experienced that firsthand in 1972 when they came looking for my cousin, they just tore my parents’ house up. They don’t ask. They don’t knock, and that wasn’t even a martial law situation.

ATC: It was bad enough under “normal” conditions. But with a civil disturbance going, no one is going to deal with a report of police misconduct.

MJB: Yes, so the chaos allowed the police to act worse. But in the end, they couldn’t control the situation either. I just finished a poem, “Eulogy for Detroit ‘67” that’s on display at the Detroit Artist Market (in context of their 50th anniversary commemoration) and for the poem, I was rereading John Hersey’s book on the Algiers Motel Incident.

In that case, the troops didn’t stop police from killing people but, when they got wind of what the police were going to do, they left — the troops didn’t stop them, the troops just left. Relatively speaking, what we’re dealing with now, in terms of police killing and repression, is on a lower scale.

ATC: For one thing, there was no video to document or deter.

MJB: No video. I also think many have come to understand that Black people will shoot back. That’s made the police a bit more cautious. People tell me “it’s no different than it was,” and I tell them it is different. It’s hard to gauge if you didn’t live through that time.

ATC: When I voted for Coleman Young (in the 1973 mayoral election), I didn’t know who he was. I voted for him strictly because he said he was going to end STRESS (a Detroit police death squad called “Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets — ed.).

MJB: He said the first thing he was going to do was get rid of STRESS and the second thing he would do was fire then Police Chief John Nichols.

Fifty Years Later

ATC: Let’s talk about the commemorations of the 50th Anniversary. What are some of the things you’re involved with and what do you think are the best ways to commemorate the anniversary?

MJB: There’s a lot going on, and I am involved in quite a bit. I spoke at the (Walter P.) Reuther Library (at Wayne State University) for the opening of their photo exhibit on Detroit ’67. Any time we get Americans to look at history, that’s a good thing. People don’t know what happened.

Too many people are operating off of the superficial myth that Black people were just looting and burning down stuff. What we just discussed about how it started is rarely a part of the conversation. When the snipers are mentioned in mainstream media, the story is that the snipers were there to keep the police from coming in so people could loot and burn.

Most of the journalists don’t know the history, and what they know is not from the perspective of the Black experience. I think what the commemoration is doing — I know the archivists; I know many of the organizers — is that they’re trying to bring the full story forward. Otherwise they wouldn’t have asked me to speak (laughs), and the others that I see that are also a part of this effort.

It’s crucial to talk about what precipitated it, to really talk about how racist City of Detroit institutions were during that period. Despite the fact that Black people had prospered because of economic opportunities (primarily auto jobs), at the same time we were still subject to all kinds of abuse, especially from the police department.

There had been the destruction of Black Bottom (the center of historic Black Detroit) to construct I-375. [Many residents in that longstanding community relocated to the west side area where the ’67 rebellion would begin — ed.]

ATC: The irony of the destruction of Black Bottom is that it forced housing integration in Detroit and created most of the “white flight” from the city. More whites left Detroit before 1966 than between 1967 and 1990. So the idea that ’67 was the start and main cause of white flight is actually wrong. But that integration was the cause of much strife in Detroit.

MJB: Yes, opening up housing was the cause of many white people leaving Detroit and, in some cases, moving into housing stock that wasn’t as good as what they’d left because they didn’t want to live near Black people.

ATC: And the real estate agents’ block busting —- pressuring whites to sell in panic once a Black family moves nearby, to beat the drop in property values.

MJB: Yes, but Black homeowners were not the people who were rebelling. For the most part, they were not interested in setting anything on fire because they owned those homes. The idea of everyone participating and the whole city being in flames is a myth that projects the idea that Black people were uncontrollable and unreasonable.

At the time, for instance, my family was living in Conant Gardens and the only thing that directly affected us in terms of the rebellion was that fact the National Guard was on Pershing High School’s football field.

A friend of my daughter asked me what we did during July ’67, and I said, we left and went to Expo 67 Montreal (the World’s Fair). She asked if we had to board our house up and I told her there was nothing happening in Conant Gardens. This was a question from an intelligent 35-year-old Detroiter who just has the image of the whole city being in flames, and that’s not what happened.

People were in those situations like at 12th and Clairmount — many people were renters. That doesn’t get considered.

ATC: Yes, my grandmother lived over there by Sacred Heart Seminary (where the statue of Jesus was painted Black) and there were blocks of apartment buildings.

MJB: And that was where much of the activity occurred. Those dimensions are left out of understanding what happened 50 years ago. The representation in the news at the time was so slanted.

ATC: If you go back and read the newspapers it’s amazing how they characterized it.

MJB: Talk about fake news! The Detroit Police Department used to have an Officer of Information and whatever happened, the Officer of Information would release information that the newspapers would print verbatim as if it were fact. That would be incredibly prejudicial to anybody that went to trial after being arrested in an incident covered that way. Reporters often didn’t bother to get another opinion.

Thank God we had the Black-owned Michigan Chronicle. When I got out of jail after they ransacked my parents’ house (in 1972) and went back to work, Dudley Randall said “call Nadine Brown” (prominent Chronicle reporter) and she got the story. Otherwise, there was no way. There was no counter narrative.

That’s why there’s some much ignorance about what happened. Even when the feds did an investigation and released the Kerner Commission Report — which was very insightful, citing racism, price gouging, overcrowding and police abuse — it didn’t change anything. Most went right on with business as usual.

ATC: And it was a New York Times bestseller, everybody was reading it.

MJB: Well, readers were. You and I read it, but many just shut down and white people who hadn’t left because of housing desegregation began to leave; that really accelerated after Coleman (Young) was elected. This is related to a flat-out white resistance to Black authority.

ATC: You’ve touched on some of this stuff, but, as an educator, what would you want younger people to know about Detroit ’67? What do you think needs to be emphasized?

MJB: I’ve been quoting our friend, the late Ron Scott. We had no say in how we were being governed. We had no real political power, were regarded by the powers that be at the time as insignificant. Then Mayor Cavanaugh, a liberal, was trying to move things forward, but we didn’t have real representation in Detroit government.

I remember reading the memoirs of Arthur Johnson (Black civil rights leader, NAACP leader, Coleman Young adviser) who said that he and Damon Keith and the NAACP were dealing with issues of police repression and they weren’t taken seriously in the mayor’s office. After ’67 white leaders came to them, asking: what happened?

ATC: I have to re-read Heather Thompson’s Whose Detroit? My guess is that Mayor Cavanaugh was not trying to be a “Law and Order” candidate but was trying to thread the needle and appease white people by not antagonizing the police. The political calculus wasn’t sharp enough.

MJB: According to Judge Dalton Roberson (Sr.), Cavanaugh owed his election in 1961 to Black people. If you got the Black vote, even back then, you only needed a small percentage of white voters to win.

Instead of dealing with issues of police repression they just ended up sending a lot of young Black men to Vietnam to fight and creating units in Detroit like STRESS (under mayor Roman Gribbs) that killed with impunity the way they killed my brother and Hayward.

[Editor’s Note: Melba’s brother John Boyd, cousin Hayward Brown and their friend Norman Bethune were involved in militant anti-drug activity in the turbulent period following the 1967 rebellion. Shot at by plainclothes cops, they went underground. Boyd and Bethune fled to Atlanta where they “were subsequently killed under highly suspicious circumstances in a blazing shootout with police between February 23 and February 27, 1973” (Heather Thompson, Whose Detroit?, 149). Hayward Brown was acquitted in three separate murder trials where he was defended by the revolutionary Black attorney Kenneth Cockrel.

Additional details in “The Fire Last Time” by Mark Binelli, The New Republic, 4/6/17, https://newrepublic.com/article/141701/fire-last-time-detroit-stress-police-squad-terrorized-black-community.

The publicity about police behavior in this case was one of many factors that led to Detroiters demanding the abolition of STRESS. —ed.]

July-August 2017, ATC 189