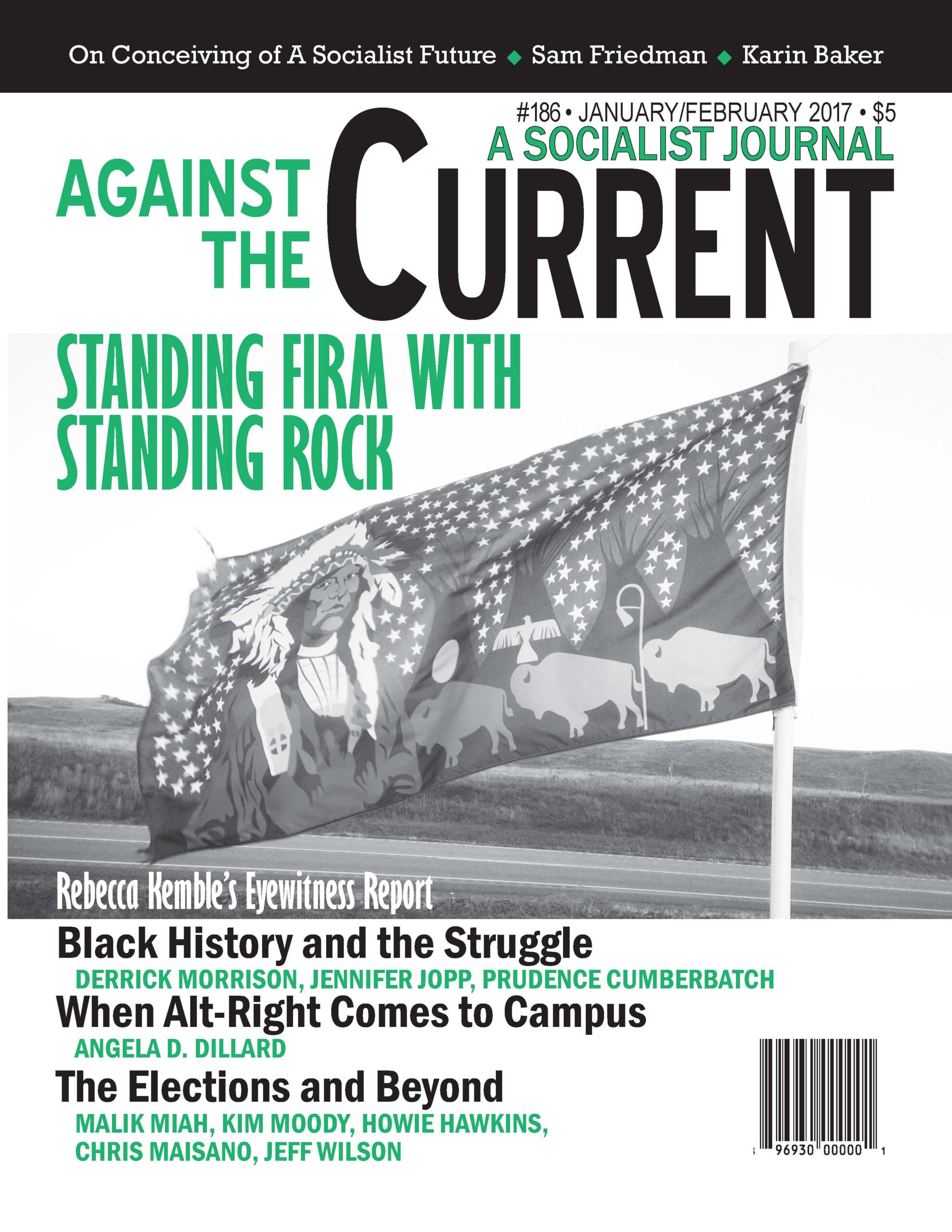

Against the Current, No. 186, January/February 2017

-

Fighting Back for Survival

— The Editors -

Obama's Legacy & the Rise of Trump

— Malik Miah - The Black Lives Matter Response to Trump

-

Eyewitness at Standing Rock

— an interview with Rebecca Kemble -

Canada's State of Reconciliation

— Gayatri Kumar - New Trial for Rasmea Odeh

-

MA Stops Charter School Expansion

— Dan Clawson & John Fitzgerald -

Chicago Teachers Settle Contract

— Robert Bartlett -

When the Alt-Right Hits Campus

— Angela D. Dillard - Putting the Racist Flyers at University of Michigan in Context

- Faculty & Staff Statement Against Racism

-

Creating a Socialism that Meets Needs

— Sam Friedman -

A Better World in Birth

— Karin Baker - US Politics After November

-

Who Put Trump in the White House?

— Kim Moody -

The Green Party After the Election

— Howie Hawkins -

Stein-Baraka Ticket

— Howie Hawkins -

Hope in Dark Times

— Chris Maisano -

Trump Not "Exceptional"

— Jeff Wilson -

Actually, I am Anti-Police

— Alice Ragland - Black History Retrospective

-

Birth of the Abolitionist Nation

— Derrick Morrison -

"The Slave-Holding Republic"

— Jennifer Jopp -

How "Race Neutral" Policy Failed

— Prudence Cumberbatch - Reviews

-

Survival Is the Question

— Michael Löwy -

Macaroni & Cheese and Revolution

— Ursula McTaggart

Derrick Morrison

The Slave’s Cause

A History of Abolition

By Manisha Sinha

Yale University Press, 2016, 784 pages, $25 paper.

“‘Our Country is the World — Our Countrymen are Mankind’ was the motto that adorned the Liberator’s masthead from 1831 to 1865. As [William Lloyd] Garrison’s adoption of Thomas Paine’s slogan indicated, abolitionists, especially Garrisonians, developed a transnational appeal seeking to harness progressive international forces against slavery.” (Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause, A History of Abolition, 339. All page references are to this title unless otherwise cited.)

“African Americans invented a popular transnational antislavery tradition, the annual celebration of British emancipation, the first of August…. In 1836 a committee of New York’s black abolitionists…arranged the first mass celebration of August First. In his address [Samuel] Cornish criticized the ‘weak and foolish’ aspects of British abolition, namely, slaveholder compensation and the apprenticeship system, but noted that while eight hundred thousand slaves in the West Indies were free, over two million remained enslaved in the United States.” (340)

“Despite his personal commitment to radical pacifism, Garrison had never hesitated to defend the Haitian Revolution and slave rebels, starting with Nat Turner.” (417)

“[David] Ruggle’s brand of practical abolitionism was replicated in Boston, where blacks took the lead in fugitive slave rescues. In 1836 a group of black women stormed the courtroom of Chief Justice [Lemuel] Shaw to whisk two enslaved women, Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates, to safety.” (385)

“The local abolitionist Dwight Janes, who argued that the Africans ‘had a perfect right to get their liberty by killing the crew and taking possession of the vessel,’ immediately alerted Lewis Tappan and [Joshua] Leavitt. Tappan, Leavitt, and [Simeon] Jocelyn organized the Amistad Committee to ‘receive donations, employ counsel and for the protection and relief of the African Captives’…. The Amistad case also united abolitionists across factional lines, the appeals of the committee appearing regularly in Garrisonian newspapers…. The Amistad Committee became a model for abolitionist committees formed to free imprisoned abolitionists….” (407)

THESE ARE JUST some of the views and actions described in Manisha Sinha’s monumental study. Throughout close to 800 pages, Sinha, a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, covers the trans-Atlantic antislavery movement, principally in Britain and the United States, as it developed in the late 18th and first half of the 19th centuries.

The cause of abolition was an inextricable part of the Democratic Revolution, a series of upheavals that saw the mobilization of the agrarian and urban laboring classes under the leadership of the new commercial and landed elites to overthrow and destroy the power and privileges of monarchy and aristocracy.

Republican Risings

That process is bookended by the Dutch Declaration of Independence from the Spanish Empire in 1581 and the U.S. Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Within this framework, the British colonists of North America fashioned not only a republic, but the most democratic to date.

As historian Sean Wilentz noted, “Nothing like the articulate democratic outburst that gripped America in 1776 had occurred anywhere in the world since the days of the Levellers and Diggers.”(1)

The “Levellers and Diggers” is a reference to the popular groups organized during the English Revolution of the 1640s. That revolution, which saw Oliver Cromwell and the novel New Model Army establish a republic called the Commonwealth, was finally consummated — after the return to monarchy in 1660 — in 1688 when the Dutch Republic’s William III became king.

A constitutional monarchy, with the supremacy of the English Parliament clearly delineated, was the product. William III, the commander of the Dutch Army and schooled in the workings of parliamentary bodies in the United Provinces of the Netherlands, proceeded to organize a democratic foundation for the rule of the big English merchants and landholders.

Religious dissent, or toleration, was legalized and a Bill of Rights elaborated. Of course, the overturn of the rule of James II was due in no small part to the army that William brought with him. According to Jonathan I. Israel:

“The invasion army consisted of 14,352 regular Dutch troops, a massive artillery train, and 5,000 [French Protestant] Huguenot, English, and Scots volunteers, making a total of over 21,000 men…. To carry the invasion force across to Britain, the admiralty colleges, chiefly of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, amassed some 400 transport vessels (ninety alone for the horses) and a war fleet of fifty-three vessels, to escort them. Diplomatic observers at The Hague were stunned by the speed and efficiency with which the Dutch armada of 1688 was fitted out. In terms of ships the Dutch invasion fleet was some four times as large as the Spanish armada of 1588…. Measured as an organizational accomplishment, the Dutch invasion of Britain, in November, 1688, marks the high-point of the Republic’s effectiveness as a European great power.”(2)

Unlike the invasion of another William in 1066, William III and his army were greeted with popular mobilizations and parades throughout England and Scotland, especially in London. The army of James II disintegrated and the monarch fled to consult his role model — Louis XIV, the absolute monarch of France.

In the seven provinces comprising the Dutch Republic and in England’s constitutional monarchy, sovereignty — the power to make laws — resided respectively in the Dutch provincial bodies and in the English Parliament.

Most government officials in the Netherlands were appointed for life from special lists. The members of the English House of Lords had similar status, but the House of Commons, elective, did not. The English franchise, or male suffrage, was extremely limited. No suffrage existed in France since sovereignty was vested in one person — the king.

In stunning contrast, the North American Republic took off in the direction of popular sovereignty. A new type of representative democracy thus arose. Wilentz writes:

“In Maryland, armed uprisings by militiamen precipitated a significant reduction in property requirements for voting and won an expansive Declaration of Rights as part of the new state’s constitution (one of seven such declarations adopted around the country). New York, New Jersey, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and South Carolina also significantly liberalized their suffrage laws. (Massachusetts and Maryland, as well as New York, nearly adopted a minimal taxpaying requirement.) Religious tests that excluded all but Protestants from the franchise, common throughout the colonies, were dropped everywhere except in South Carolina. In North Carolina, Georgia, and (in some counties) New Jersey, as well as Pennsylvania, voting by written ballots became the norm, and the New York convention proposed trying the system since some had claimed it ‘would tend more to preserve the liberty and equal freedom of the people.’(3)

It was this egalitarian thrust, backed by committees and armed groups of farmers and urban artisans, that marked the depth of democracy in the North American Republic, and seemingly meant the death knell for slavery.

“[John] Adams,” writes Sinha, “who never owned slaves, was for gradual emancipation but feared a race war in the South. Sam Adams and John Hancock pushed for a law to abolish the slave trade to Massachusetts and condemned slavery. [Benjamin] Franklin, like some other antislavery founding fathers, for example, John Jay of New York, was a slaveholder. He came late to abolition even though he had published abolitionists like [Benjamin] Lay and [Ralph] Sandiford and was an admirer of [Thomas] Tryon, [Granville] Sharp, and [Anthony] Benezet. He and Jay eventually freed their slaves and, along with Alexander Hamilton, lent the prestige of their names to the abolition movement after the war.” (41)

The Contradictory American Scene

This explosion of egalitarianism took graphic shape over three important dates in 1787 — six years after the military victory of the American Revolution. On May 14 the 13 former British colonies sent delegates to a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

On June 7, after twelve singularly-minded men sat down in London to form a committee to fight slavery, it was decided to call that body the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

On September 17, the Philadelphia Convention concluded with a document called the Constitution of the United States, asserting in Article I, Section IX, “The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight….”(4)

In other words, the African slave trade would likely be abolished in 1808! What an extraordinary development! It demonstrated the power of an idea whose time had arrived. It illustrated the potential of building a powerful, trans-Atlantic antislavery movement.

William Wilberforce became the spokesperson for the movement in the House of Commons. “British abolitionists,” Sinha writes, “perfected the tactics of lobbying, petitioning, publication of antislavery tracts, and boycott of slave-produced goods, particularly sugar…. In 1792 some four hundred thousand people signed abolitionist petitions….” (101)

In the newly-minted United States, abolitionists waged a state-by-state campaign to end slavery. Three years before 1787, American egalitarianism had already abolished slavery in the New England states and Pennsylvania. (76)

The revolutionary democrats counseled compromise on the U.S. Constitution, because they felt that in time the same emancipation course would take hold in the southern states.

“Revolutionary scruples,” asserts Sinha, “prevented the Constitution Convention from using the words slaves and slavery ” (77); but in Article I, Section II, representation in the Congress and taxes were to be based on slaves as “three fifths of all other Persons.” And in Article IV, Section II the Constitution pronounced, “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.”(5)

This clause reveals the fundamental contradiction of slavery in a republic, the contradiction of juxtaposed areas of slavery and non-slavery under one government. Such incongruity could only produce one immediate result: the fugitive, or runaway slave.

The fugitive slave reflected the intensification of the contradiction. The fugitive slave inspired and drove forward the abolitionist movement. Legal precedent in 1772 established that any West Indian slave brought to Britain was automatically free.

This was the contest that would rock the United States: the growth of resistance to the expanding use of the federal government by the southern slaveholder to capture fugitive slaves in the north.

The Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850 allow us to measure the forces in immediate contention, and the subterranean economic changes that were shaping the terrain of struggle.

The first act arose out of a contest between Pennsylvania and Virginia. John Davis, a slave, had been taken by his master to Pennsylvania which required that all slaveholders register their slaves in any travel through the state. The Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, PAS, discovered that Davis had not been registered. They tracked his movement back to Virginia, informed him of the situation and brought him back to their state. The subsequent legal fight resulted in the passage by the U.S. Congress of the 1793 Act. (Sinha, 95)

The ability of the PAS to monitor a slaveholder’s movement and free his slave in Virginia and return with him to Pennsylvania was a phenomenal organizational feat. PAS had the support of not just the state government but tens of thousands of ordinary citizens.

Social and Industrial Revolution

The Virginia slaveholder had the power of the federal government behind him. The slaveholders and many members of Congress, however, were worried. The refusal of King Louis XVI to agree to a constitutional monarchy had pushed the French into republican territory. The national assembly, the Convention, put the King on trial and executed him in January of 1793.

Saint Domingue (now Haiti), the richest sugar-producing colony in the New World, was engulfed in the flames of slave revolt. The following year the Jacobin-led Convention abolished slavery in Saint Domingue and other French colonies. The U.S. slaveholders were tightening their grip in this atmosphere.

Coupled with these political events, economic forces unleashed in Great Britain (the union of England and Scotland in 1707) were revolutionizing production and agriculture. As Sven Beckert observed, the factory, the mill, was the newest invention of the “mechanization of cotton spinning….”(6)

The first mill in 1784 brought together “a few newfangled spinning machines…orphaned children…and a supply of Caribbean cotton.” The location was Manchester, England. Alongside powerful British merchants came the manufacturer.

“In eighteenth-century India, spinners required 50,000 hours to spin a hundred pounds of raw cotton….” The use of spinning machines allowed the British manufacturer to “…spin the same amount in just 1,000 hours. By 1795 the manufacturer needed just 300 hours.”

Beckert writes: “Between 1780 and 1800, output of cotton textiles in Britain grew annually by 10.8 percent, and exports by 14 percent; already in 1797 there were approximately nine hundred cotton factories.”(7)

This expansion of production required a corresponding leap in agriculture. Slaveholders in South Carolina and Georgia began to shift from tobacco to cotton in the late 1780s. Eli Whitney’s invention of the mechanized cotton gin in 1793 solved the problem of removing seeds from cotton. “Overnight, his machine increased ginning productivity by a factor of fifty.”

Cotton planting “spread rapidly after 1793 into the interior of South Carolina and Georgia…. In the 1790s, the slave population of the state of Georgia nearly doubled, to sixty thousand. In South Carolina, the number of slaves in the upcountry cotton growing districts grew from twenty-one thousand in 1790 to seventy thousand twenty years later, including fifteen thousand slaves newly brought from Africa.”(8)

As global trade and big business were fastening the hold of slavery on the South, the system was not about to wither away. Nonetheless, the British Parliament and the U.S. Congress passed legislation in 1807 abolishing the African slave trade, effective January 1, 1808. This legislation cleared the way for British abolitionists to now target slavery itself.

But new allies would come onto the scene. The spread of the factory system was the product of the Industrial Revolution. Factory workers and manufacturers — the owners of the factories — were the new social phenomena.

It was a combination of a revolt by sixty thousand slaves in Jamaica, the demands of factory workers for radical extension of the franchise, and big manufacturing money applying its own pressure, that effected a reformation of Parliament. As Sinha sums up, “The Reform Act … and abolitionist petitions ensured the passage of emancipation in 1833.” (213)

Rising Conflict

This is a brief sketch of the British process. The North American process would run a similar but more drastic course.

The egalitarianism of 1776 would ensure that the rise of a new manufacturing class centered on textile mills, metal-working factories, and railroads would find political expression inside the U.S. Congress. Rather than a slave uprising, fugitive slaves numbering possibly 150,000 between 1830 and 1860 would also be a central part of the equation for change. (382)

Additionally, the evolution of abolitionist tactics was a necessary part of the mix. Sinha writes, “Black abolitionists established the permanent organizational apparatus of the abolitionist underground, the vigilance committees of the 1830s.”

The New York Committee of Vigilance “’outed’ kidnappers and slave catchers” and “assisted fugitive slaves and rescued kidnapped southern and local free blacks…By the 1840s and 1850s organized abolitionist assistance to ‘freedom seekers’…became popularly known as the UGRR [Underground Railroad].” (384, 388)

Sinha chronicles these activities using diaries, newspapers, and histories written by participants. The abolitionists were the vanguard in the fight against the mushrooming power of the slaveholder, an expansionist power which required more and more territory. To satisfy this craving the federal government even floated proposals to buy Cuba and Nicaragua. (496-7)

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 capped the effort to throttle the runaway. “It criminalized any help rendered to suspected fugitives with up to six years imprisonment and a thousand-dollar fine, encouraged the kidnapping of free blacks, and forced northern citizens to act as slave patrollers by allowing federal marshals to form posse comitatus of adult armed citizens to apprehend runaways.”

No free African-American was safe, causing “(n)early half and sometimes entire congregations of black churches in Boston and upstate New York …: to flee to Canada. (501)

Alongside the repression and disruption of abolitionist networks, anti-slaveholder expansionist sentiment began to find expression in the arena of electoral politics. Sinha outlines the rise of the Liberty Party in 1840 and the Free Soil Party in 1848. The latter absorbed the former and touted the slogans “No more Slave States and no more Slave Territory,” and “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Speech, and Free Men.” (482)

These parties represented the first steps of the manufacturers — who required “free labor,” in alliance with farmers and would-be farmers — who required “free soil.” Their expansion necessitated slaveholder restriction. That programmatic combination finally crystallized in the form of the Republican Party in 1854. (497)

As Robin Blackburn contended, “[Karl] Marx’s argument and belief was that the real confrontation was between two social regimes, one based on slavery and the other on free labor: ‘The struggle has broken out because the two systems can no longer live peaceably side by side on the North American continent. It can only be ended by the victory of one system or the other.’ In this mortal struggle the North, however moderate its initial inclinations, would eventually be driven to revolutionary measures.”(9)

To sum up, the abolitionists were the consistent defenders of the legacy of 1776. They stood behind the civil liberties and egalitarianism represented by the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

Slaveholders did not allow in the South any right to free speech and assembly on the question of antislavery. Slaveholder expansion threatened to overturn not only civil liberties, but the democratic foundation of the Republic.

Coupled with the slaveowners’ opposition to the program of the manufacturers, this facilitated an alliance of the Republicans and abolitionists. Simple legislation, as in the British case, would not do. The slaveholders were not thousands of miles away, they were in the house. In fact, they controlled the government of the house.

A civil war would have to be waged to decide the matter. We know the outcome of that battle.

Manisha Sinha’s work is an excellent text. It is encyclopedic and can be read in parts or as a whole. The sections on Angelina Grimké, Frederick Douglass, and John Brown are exceptional. How the abolitionists utilized the tools of democracy to fight slavery provides lessons for today’s supporters and activists in the fight for social justice.

On the mobilization of public opinion, the abolitionists have few equals. Sinha has brought their example to life.

Notes

- Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2005),29.

back to text - Jonathan I. Israel, The Dutch Republic, Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806 (Oxford University Press, United Kingdom, 1995), 849-850.

back to text - Wilentz, 28.

back to text - The Constitution of the United States of America and Selected Writings of the Founding Fathers, Compilation by Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2012, 807-808.

back to text - Op cit., 803, 812.

back to text - Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton, A Global History (Random House LLC, New York, 2015), 68.

back to text - Op. cit., 56, 66, 67.

back to text - Op. cit., 102, 103.

back to text - Robin Blackburn, An Unfinished Revolution: Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln (Verso, London and New York, 2011), 11.

back to text

January-February 2017, ATC 186