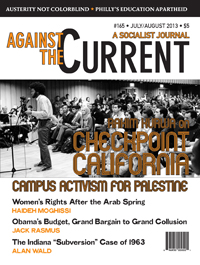

Against the Current, No. 165, July/August 2013

-

Obama: Human Rights Disaster

— The Editors -

Austerity Is Not Colorblind

— Malik Miah -

Defending Public Education in Philadelphia

— Ron Whitehorne -

Update: Chicago's School War

— Rob Bartlett -

BDS Campaign Sweeps UC Campuses

— Rahim Kurwa -

Inside the Corporate University

— Purnima Bose -

Changing Ecology and Coffee Rust

— John Vandermeer -

Austerity American Style (Part 1)

— Jack Rasmus -

Arab Uprising & Women's Rights: Lessons from Iran

— Haideh Moghissi - On Assata Shakur

- Fifty Years Ago

-

Remembering Medgar Evers

— John R. Salter, Jr. (Hunter Gray) -

The Indiana "Subversion" Case 50 Years Later

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

Marxism and "Subaltern Studies"

— Adaner Usmani -

Palestinians and the Queer Left

— Peter Drucker -

A Novel of Class Struggle & Romance

— Ravi Malhotra -

The Radicalness of the Accessory

— Kristin Swenson -

The Implacable Russell Maroon Shoatz

— Steve Bloom - In Memoriam

-

Howard Wallace, 1936-2012

— Sue Englander

Ravi Malhotra

The Gleaming Archway

By A.M. Stephen

Lexington, Kentucky: Iconoclassic Books, 2012 (originally published 1929)

274 pages, $11.99 paperback.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1929 and recently re-released by Iconoclassic Books, this novel provides a window into a lost world of class struggle and labor strife, with some passionate romance along the way. In so doing, it is a revealing portrait of a left that had a significant impact in the daily culture of the working class and yet viewed the world in strikingly different ways from contemporary anti-capitalist activists.

As Ian McKay has documented in his magisterial history of the early 20th century Canadian left, Reasoning Otherwise,(1) this was a period when socialist ideas had real influence amongst a significant segment of the population. Large segments of the working class believed that the end of capitalism was very rapidly approaching. And as Peter Campbell has written, hundreds would show up at large venues like Vancouver’s Empress Theatre to hear radical speakers preach about the evils of capitalism.(2)

Remarkably, as I detail below, this novel also contains a fictional portrayal of one of the most important socialists of his time, the double amputee and left-wing newspaper editor and orator, E.T. Kingsley.

Written by radical Canadian poet and author A.M. Stephen and set in the years preceding the First World War, The Gleaming Archway tells the story of one Craig Maitland, a socialist newspaper reporter. The protagonist is clearly based on the author whose middle name is also Maitland. An early advocate of feminism, Stephen explores some of the themes of gender relations, if in a somewhat paternalistic and confused way.

The plot itself is relatively uncomplicated. Maitland is a young, idealistic radical who takes a vacation in British Columbia’s Squamish Valley. Struggling to find meaning in his life and firmly committed to the moderate social democratic wing of the socialist movement in an era when these distinctions were less meaningful than today, he then meets a colorful cast of characters including a Russian émigré, Ivan Kolazoff, an aristocratic Oxford-accented British gentleman, Mr. Featherstone, and “Cave Man,” the uncouth and physically intimidating union organizer Bud Powers.

Maitland falls deeply in love with a charming married woman, Mrs. Paget, only to realize the futility of the match. He subsequently bonds on a camping trip with a budding feminist colleague, Madge Brett, but ends up marrying Stella Shannon on a whim, after meeting her in a seedy gambling house in Vancouver’s Chinatown.

After some plot twists and much poetic description of the stunning British Columbia landscape, Maitland, now widowed, is reunited with his also widowed first love, Mrs. Paget.

E.T. Kingsley Portrayed

While a novel of significant interest in its own right, the most remarkable aspect of The Gleaming Archway is undoubtedly the unexpected fictional portrayal of socialist activist and double amputee, E.T. Kingsley in the character of Tacey, a newspaper editor in real life and in Stephen’s novel.(3)

Born in antebellum New York State in 1856 and one of the greatest socialist intellectuals in Canada of his time, Kingsley was disabled in a railway accident in Montana in 1890. After he lost both his legs, he radicalized while recuperating and soon joined Daniel De Leon’s Socialist Labor Party (SLP), known for its dogmatic brand of Marxism.

A candidate for the House of Representatives in 1896 and 1898 in California on the SLP ticket, where he also played a role in one of the earliest known Free Speech fights years before the IWW was even founded, Kingsley eventually broke with the SLP and moved to British Columbia in 1902. There he helped found the Socialist Party of Canada and became editor of its radical paper, the Western Clarion, and in 1919 founded the short-lived Labor Star.

A fiery orator known for his skills speaking to the masses on street corners and nicknamed the “Old Man,” Kingsley is one of the few men ever to run for legislatures in both the United States and Canada. He ran three times for the British Columbia legislature and another three times for the House of Commons. His accomplishments also raise profound questions for disability theorists trying to better understand how people with disabilities lived and struggled in this era.

To find a fictional portrayal of Kingsley, a thinker much neglected in histories of the Canadian left, is thus an extraordinary development and a fine tribute that merits serious attention by scholars.

In Stephen’s hands, Tacey is portrayed with deep affection and respect and with great accuracy as editor of the fictional Beacon. Although Tacey is depicted in Stephen’s novel as a single-arm amputee rather than a double-leg amputee like Kingsley, numerous parallels leave no doubt that Tacey is intended as a portrayal of E.T. Kingsley. In describing a talk given by Tacey, Stephen writes:

“Despite the tricks of the politician and a catering to the careless vernacular of the working-man, Tacey’s address was logical, convincing and suggestive of a powerful intellectual grasp of the subject of economics. There could be no doubt of the man’s sincerity. The gospel according to Marx was his Bible and the idealistic social State was his religion. He would as willingly die for his dream as any martyr for his interpretation of a Scriptural comma. Body and soul, his idea possessed him. Yet, mellowing his orthodoxy, was a glowing humanitarianism — a great kindliness that drew these rough men to him and held them while he chastised them for their own good.”

Here one has all at once the rigid orthodoxy for which Kingsley was legendary, his enormous commitment to the working class, and his particularly keen intellect, as he was described in police intelligence documents of the time as “unquestionably one of the most dangerous men in Canada, having education and capacity and knowing how to win the sympathies and acclaim of the more ignorant classes of the community.”

E.T. Kingsley’s sensitive and historically accurate depiction in this novel makes The Gleaming Archway worth reading all by itself. It also strongly implies that Stephen personally knew Kingsley in the small world of radical British Columbia. Advocates of socialism from below would profit from learning more about Kingsley’s unique world view at a time before the lines between reform socialism and revolutionary Marxism were so rigidly drawn.

A Flawed Vision

The Gleaming Archway remains stamped, it must be said, by the blinkered political prejudices of the era. There is significant reference to the notion that socialism is inevitable. Its descriptions of Vancouver’s Chinatown are avowedly racist, depicting the Chinese Canadians who briefly make appearances in the novel as one dimensional straw characters. Stephen writes:

“Turning south from Hastings Street, they soon found themselves in the Oriental section of the city. It merged with the area given over to the underworld and, like a semi-tropical parasite, seemed to thrive upon the atmosphere of lust and crime emanating from the dives and gambling places.” (180)

Its portrayal of First Nations peoples is similarly racist and crude. While Stephen had a proud history of advocacy for feminist causes such as the promotion of birth control and legal reform to empower women’s legal status in family law, he portrays many female characters in his novel in a largely stilted way. He depicts female jealousy of perceived sexual rivals in rather stereotypical ways. While this may be partly attributable to his tendency to wax poetic, one cannot help but perceive it as patronizing.

Some small deficiencies in the edition are somewhat jarring. It appears rushed as punctuation is often missing at the end of sentences. Too much of the plot, including major surprises, is given away on the back cover. And the publishing house has assumed that the novel is set in the year of publication (1929), when the context makes evident that the story takes place prior to the First World War and the overthrow of the Czarist Regime during the Russian Revolution.

Iconoclassic Books is nevertheless to be lauded for reissuing a work that merits greater attention by scholars. Its minor flaws aside, Stephen’s lost tale awaits the judgement of literary scholars of the 21st century.

Notes

- Ian McKay, Reasoning Otherwise: Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada, 1890-1920 (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2008).

back to text - Peter Campbell, Canadian Marxists and the Search for a Third Way (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999).

back to text - I thank Mark Leier for drawing this to my attention.

back to text

July/August 2013, ATC 165