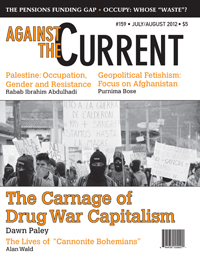

Against the Current, No. 159, July/August 2012

-

Swing of the Pendulum?

— The Editors -

Immigrant Youth Victory!

— The Editors -

Rolling Back Reconstruction

— Malik Miah -

The Pensions Funding Gap

— Jack Rasmus -

The Media's Dirty War on Occupy

— Jacob Greene -

"Authoritarian Populism" and the Wisconsin Recall

— Connor Donegan -

Marching for Life, Water, Dignity

— Marc Becker -

Geopolitical Fetishism and the Case of Afghanistan

— Purnima Bose -

Living Under Occupation

— Rabab Ibrahim Abdulhadi - Samiha Khalil (1923-1999), Resistance Organizer

-

Drug War Capitalism

— Dawn Paley -

Cannonite Bohemians After World War II

— Alan Wald -

Why Music Must Be Revolutionary -- and How It Can Be

— Fred Ho - Reviews

-

Letter on Trayvon Martin

— Christina Reseigh -

Soldiers of Solidarity

— Mike Parker -

Organizing Is About People

— Carl Finamore -

An Unfinished Revolution

— Derrick Morrison -

The Black Panthers in Portland

— Kristian Williams

Rabab Ibrahim Abdulhadi

Rabab Ibrahim Abdulhadi describes growing up in Palestine after the 1967 war, when Lelia Khaied emerged as a role model for young Palestinian girls. The author describes everyday resistance and the role women—including her mother and aunt—played. PDF of an extended edition for the web.

“From Brazil to Vietnam, from the Dominican Republic to Algeria, from Mali to Indonesia, from Bolivia to Greece, US fleets, air force, and intelligence networks were undermining the achievements of the post-war period and arresting the tide of history. The 1960s were indeed America’s decade. The 1970s shall be the decade of its dismantlement and complete undoing”. —Leila Khaled, My People Shall Live! (1973:89-90)

IN HER AUTOBIOGRAPHY, Palestinian militant Leila Khaled calls the 1960s “America’s decade,” pointing to several spots around the world where the U.S. intervened against people’s struggles as evidence that the decade was not a cause for celebration. Assassinated leaders of communities of color and the Third World movements, such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Patrice Lumumba would probably have agreed with Khaled had they been allowed to live long enough beyond the 1960s to assess that decade. Khaled’s words and the fate of African and African-American leaders contradict the celebratory tone of the 1960s (even if her expectations for the 1970s would prove to be overly optimistic).

As I sat through the first two days of the New World Coming Conference listening to speakers, I expected to hear references to the 1967 Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights and the Sinai Peninsula. However, I found it at best curious and at worst alarming that, save for one plenary speaker, The Occupation simply did not come up even peripherally.

It is curious that while Frantz Fanon’s work on Algeria, The Wretched of the Earth was theoretically cited by several speakers, the actual struggle about which Fanon wrote and in which he participated seemed not to have seeped into the consciousness of conference participants. And it is alarming that despite repeated references to the U.S. war in Iraq and Afghanistan, there seemed to be no knowledge of the history of U.S. intervention in the Arab world, nor of the resistance movements to such intervention.

Whose 1960s are we talking about, then? By placing the 1967 Israeli occupation and the Palestinian anti colonial resistance (including women’s militancy) at the center of my analysis, I offer an alternative reading to the assumption too often made by students or scholars of U.S. social movements, that the dynamics of activism in the United States are necessarily applicable to all social movements around the world.

Our 1960s

To refresh our memories, then, let me share several major developments in our part of the world that took place during the 1960s, with which some readers may be familiar:

• It was during the ’60s that the liberation of Yemen from British colonialism took place with the support of fighters from all over the Arab world.

• The ’60s witnessed the decolonization of Algeria. While Fanon’s theory of revolution continues to be widely quoted, Fanon seems at times, to be lifted out of the context in which he acted, operated, theorized, struggled and negotiated on behalf of and alongside the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN).

• The ’60s witnessed the founding the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1965. At the same time, the Palestine National Council, the first Palestinian Parliament in Exile, was founded.

• In 1965, the General Union of Palestinian Women (GUPW) was also founded. The insistence of GUPW that a Palestinian is one whose mother or father is a Palestinian undermines the claims of colonial feminists who continue to suggest that Arab and Muslim women are submissive and that the United States is the most liberating space in terms of gender justice.

• Most centrally to my subject matter, the 1960s was the decade when Palestinians experienced the occupation of the rest of their historic homeland and the expansion of Israeli rule over Egyptians and Syrians in addition to the Palestinians.

Experiencing Occupation — Situated Knowledge

The ’60s were my formative years. They were also when The Occupation took place. I was only 12 years old in 1967 when Israel occupied the rest of Palestine along with other Arab lands. The Occupation shaped and framed the person that I am today along with an entire generation of Palestinians’, whose course of life was altered in more ways than we could have imagined.

A little over 45 years ago, on June 5, 1967, Israel occupied the rest of Palestine along with other Arab lands. Things that were Arab ceased to be central to our lives: road signs, currency, food labels, clothing labels, birth certificates were now all issued in Hebrew, the official language of the occupation. While Arabic continued to be used, documents were considered official only if they were “authenticated” in Hebrew.

Curfews were imposed lasting at times for weeks. During this time, jeeps full of men speaking a foreign language none of us understood, would roam the streets of my hometown, Nablus. When the curfew was partially lifted we, young girls in blue and white striped elementary public school uniforms, would be allowed to go to school. The first time the curfew was lifted after 1967 occupation, we arrived in our classrooms to find that Palestine was erased from geography books and its history deleted from the Israeli-sanctioned curriculum.

Almost half of the teachers refused to return to teach, citing the colonial curriculum as a reason for their action. As one put it: “I can’t teach that Palestine was always Jewish and we are parasites.” (Epps, 1976: 77, as cited in The People’s Press Palestine Book Project, 1981: 128). Palestinian teachers who returned to their jobs, however, did not accept the Israeli-imposed curriculum and instead sought to teach the younger generation of Palestinians growing up under occupation about our history and roots so that we might not forget who we were or where we came from. In doing so they risked imprisonment and other punitive measures.

This was not the first time Palestinian teachers defied those who ruled over us. During the Jordanian rule over the West Bank (1950-67), Palestinian teachers ignored the history the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan sought to impose on Palestinian school curriculum and insisted on teaching a counter-hegemonic curriculum — one that exposed the role Jordan played in collaborating with the Zionist movement before 1948 and the Israeli government since.

As young girls approaching puberty, we would walk to school ever so carefully, seeking to avoid the stares and harassment of young Palestinian men. However, we were not as successful in avoiding those Israeli jeeps positioned along the road, packed with young men in full military gear and guns pointed at us. But they were not speaking a foreign language now. In their broken Arabic, the Israeli soldiers were using the kind of words that our parents would never allow us to utter.

Yet at such a young age, we somehow knew that we could not go home to tell our parents about this sexual harassment (as we did regarding the young Palestinian men). In the face of the occupation’s military might, our parents were helpless and defenseless, thus failing at the most basic responsibility of parenthood — protecting their offspring.

At that early age, we learned what The Occupation meant and how it invaded and dominated every aspect of our lives. We excelled in understanding power relations — and when some of us later read Foucault’s analysis on power and knowledge we recognized some of the patterns we had experienced growing up: The signs were all over the place even if we could not spell them out in Hebrew.

We learned early on about the scarcity of resources and the harsh reality of The Occupation. We understood why we had to be careful not to let the faucets run; why water was so precious; why the neighbors’ son was killed; or why their home was demolished. We knew that nothing could be done if we missed our cousins; the chances of seeing relatives who lived in Amman, Cairo, Beirut, Kuwait or Saudi Arabia were almost nonexistent. The roads were closed.

The Bridge between the West Bank and Jordan, now controlled by the Israelis, became an international border crossing that was impossible to cross. The Israeli control of border crossings with Jordan meant that no cars were allowed to travel between the West Bank and “the East Bank” (the name the Jordanian monarchy gave to Trans-Jordan after they annexed the West Bank and considered it part of the Kingdom in 1950). Instead, Palestinians traveling from Nablus to Amman, for example, would have to take one form of public transportation from their own hometowns, such as Nablus, to the Israeli border control a short distance away from the Bridge crossing. Then one had to take a bus that made the trip from the Israeli-controlled side to the Jordanian side.

Once at the Jordanian side, the passengers would take a third mean of transportation to Amman or to wherever they wanted to go in the “East Bank.” The long wait, excessive search, including body cavities, exuberant cost, and the high probability of being turned back made it almost impossible for anyone to travel except those in desperate need of crossing into Jordan such as students, patients, or family members traveling for a funeral. My siblings and I lost the annual summer trip, during which my parents would load the six of us into the car and take us for a week to Lebanon.

Occupation and Consciousness

We were not only aware of the harsh reality of The Occupation. It was during the ’60s that we first learned of the existence of the fedayeen, (or those who sacrifice themselves) of the Palestinian resistance movement. With the rise of the Arab National Movement, the Palestinian resistance movement adopted the form of guerilla warfare in the early 1950s, followed by the founding of the Al-Fatah movement a few years later. Earlier attempts at waging a guerilla warfare against Zionist settlers were evident in the 1930s, especially the movement of Sheikh Ezzedin Al Qassam, a Syrian peasant who joined the Palestinian resistance movement, and the Great Palestinian Revolt in 1936-39 (the longest workers strike in history) to fight alongside Palestinian peasants to defend their lands.

My first experience of the resistance movement was the arrival of my cousin Saji with a college friend to our home in Nablus. I remember clearly my mother hugging her nephew; Saji apologizing for imposing on us; and my mother waving him away and saying that she would call her sister, my aunt, to tell her that her son was safe and sound and that he would be arriving home in Ramallah-Bireh soon. I remember clearly Saji asking my mother not to say anything to his parents because he “was going to surprise” them.

Now that I think of it, I doubt that my mother had actually bought Saji’s story. I am almost 100% sure that she knew he was a fedayee but that she did not want to acknowledge it nor force Saji to admit it, especially in front of little kids, the oldest amongst them 12, who did not know how to keep a secret and such an exciting one at that. After taking a shower and changing his clothes, Saji and his friend left for Ramallah. A few months later, we learned from my aunt that Saji and his comrade, Ahmad Dakhil, were arrested by the Israeli military.

Arrests, detention, night raids, demolition of houses, torture and imprisonment were (and remain) regular features of The Occupation. I particularly remember the prison conditions as I used to accompany my mother and my aunt, Um Khalil, to various Israeli prisons to visit Saji, who was tortured for several months (during which no one, including his Israeli lawyer, Felicia Langer, a Holocaust survivor and a leading member of the Israeli Communist Party, or the International Red Cross, could see him) before being sentenced to seven years in military court.

Midway into the sentence, the Israeli authorities offered to release Saji on the condition that he would agree to being expelled from the West Bank, and never to return. Saji refused the Israeli offer, selecting instead to complete his sentence so he could be released among his family and community. However, upon the completion of his sentence, Saji was expelled to Jordan. “Too late” was the response of the Israeli prison authorities to Felicia Langer as she rushed to the prison where he was held (a day before he was due to be released) to show the warden the official document agreeing to release Saji to the West Bank.

Saji’s story (while not exceptional) also represents the complexity and the ever shifting Palestinian political landscape: He was arrested as a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) but seven years later Saji exited prison as a member of the Political Bureau of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), a group that split off the PFLP in 1969 over ideological differences and became the third most influential group in the PLO after Fatah and the PFLP. (Hamas and Islamic Jihad had not yet emerged as Palestinian political groups until the late 1980s.)

That Saji was able to understand the complete basis of the PFLP-DFLP split and thus choose sides while serving a sentence in Israeli jails attests to the extent of organizing that goes on inside Israeli prisons.

Women in Anti-Occupation Resistance

Around the same time of Saji’s arrest, word spread throughout Nablus that several women of college age were arrested by the Israeli military: Maryam Shakshir, Amal Hanbali, and the Nabulsi Sisters from Nablus, along with Rasmiyeh Odeh and Aisha Odeh from the Ramallah-Bireh area, followed in the footsteps of Fatima Bernawi, the first Palestinian woman to be arrested after the start of the 1967 Israeli occupation.

The Palestinian women were likened to the Algerian Jamilat whose participation in the Algerian war of liberation and refusal to confess despite extreme torture (see de Beauvoir and Halimi, 1962) turned them into legends throughout the Arab world. Following the same trajectory of the Algerian Jameelat, several years later, Palestinian women were arrested, tortured and sentenced to long terms in prison. (See for example, Thornhill, Making Women Talk, 1992)

The similarities of the French and Israeli colonial rule and the connection between the two resistance movements in Algeria and Palestine are extensive. For the Palestinians, Algeria was always present in their everyday reality: The Algerian struggle was a model to be followed for the Palestinians as they frequently invoked the Algerian victory to combat defeatism and a sense of pessimism: “If the Algerians could kick out the French colonists after 130 years, we too could end the occupation after a few years.” As schoolchildren, we used to begin our morning routine by chanting the Algerian National Anthem before we started classes. I don’t recall anyone seeing this as a contradiction with the Palestinian aspirations to liberate themselves and return to the homes from which they were expelled in 1948. My elementary school, from the second to the fifth grade (when The Occupation started), was named after Jamila Bouhayred, one of the Algerian Jameelat.

In their guerilla warfare, Algerian women militants pursued “passing” as strategy to escape the watchful eyes of their colonizers, as in Gillo Pontecorvo’s film “The Battle of Algiers,” which dramatized the Algerian war of liberation, 1954-62. Like their Algerian counterparts, Palestinian women militants also passed through Israeli checkpoints.

This strategy could not have worked without an Orientalist mindset by the colonial powers that saw Palestinian women as oppressed and hapless victims of an oppressive Arab social and cultural structure that was dominated by misogynist males. (See Said 1978. My forthcoming book, Revising Narratives: Gender, Nation, and Resistance in Palestine, explores questions of passing and gender performance more fully.)

Contrary to the claims by those I would call colonial feminists, Palestinian women were not duped by the Palestinian male militants, nor sexually seduced by the prowess of the terrorist. In fact, they were not satisfied with playing limited roles politically, socially or organizationally. Instead, they sought to be treated equally, and they saw being included in carrying out commando missions as evidence of their equality. This contradicts the conclusion, for example, of Sara Evans (1980) that women’s consciousness emerges as a result of negative experiences within the movement.

I conducted interviews with male and female former prisoners. All the women militants who were arrested in the late 1960s were released from Israeli jails through a prisoner exchange agreement between the Israeli government and Palestinian militant groups in 1985. By then, some of them had spent at least 17 years of their lives in prison. As one of the 1960 women militants said:

“We [Palestinian women members] demanded to be trained and sent on mission just like the men. We did not believe that we were less capable or less courageous. We wanted to contribute to the cause of our people in the same manner that we demanded women’s liberation and treatment on equal footing with the male comrades.”

The solidarity between the Palestinian and other anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements around the world was evident on several levels: Palestinian guerilla groups were training fighters from Nicaragua, anti-Shah regime Iranian groups, and others. During the Black September events in 1970, aid from Vietnam, Algeria and China to the “Palestinian Nation” was arriving in Amman, Jordan, where Palestinian guerilla camps were set up. (Our Roots Are Still Alive, The People’s Press Palestine Book Project 1981)

Leila Khaled

At the center of my memories of the 1960s emerges Leila Khaled, the most famous Palestinian woman commando and the role model for most of the young girls growing up under occupation. We did not dream of growing up to get married and play house. We all wanted to be like Leila Khaled!

Dreaming of becoming a militant instead of a home-maker obviously has a lot to do with the socialization of children by their environment. While it should not be surprising for a people under siege to valorize militancy or to support violence as a weapon of the weak, explaining this impulse on the part of young girls is necessary, given the colonial assumptions about Arabs/Muslims/Palestinians, and other colonized people who fight for their liberation and self-determination. This is especially true in a context such as the United States of America, where popular culture and official statements alike have no qualms in suggesting that our people are generally bloodthirsty, Jew-hating, violence-inclined, misogynist and irrational, and that those amongst us who “make it” in polite society are considered exceptions to the rule.

Leila Khaled did not escape the rule of exceptionality. Her story is constructed as an exception to the majority of Palestinian women, one who literally escaped “the patriarchal restrictions of Arab society where women are traditionally subservient to their husbands,” as a newspaper article wrote a decade ago. (Katherine Viner, “Beauty and the Bullets: What Became of Leila Khaled, the World’s Most Famous Terrorist Pin-Up?” The Guardian, Friday, January 26, 2001)

The accounts stress Khaled’s looks — how beautiful; how shiny her hair; how she had wrapped the kafiyyeh around her neck; how glamorous she looked; how beautiful her features were before she had her plastic surgeries to disguise her appearance. Every single time interviewers would sit with her, the same discussion about her looks comes up.

Her biography, written by George Hajjar, a Canadian Arab journalist, refers to Khaled as child-like. This is similar to the way in which the autobiography of Rigoberta Menchu was constructed, in which she is described as “child-like.” This is a deliberate discursive move on the part of sympathetic writers to endear a subject like Leila Khaled, whom readers might see as a horrible hijacker. Implying that she looked as innocent as a child, however, sends another message that she really didn’t know what she was doing, or that she was duped by male leaders. In Shoot the Women First (1991), Eileen McDonald writes that Khaled was trained by “her masters” and sent to hijack a plane and commit violence.

Leila Khaled’s biography is an interesting case study to the ways in which a segment of Palestinian resistance fighters in the 1960s was represented and how the members of this group saw themselves and their place in society and history. Khaled, for example, did not want to do an autobiography but she had to finally acquiesce when Hajjar would not stop pressing her until she sat down and agreed to the interview.

Recent interviews with Khaled make it clear that she had neither seen her “auto”-biography, nor its translation since she gave the interview in the late 1960s. This is particularly interesting in this age of neoliberal globalization and the insistence on “intellectual property rights.” It is also clear that Khaled didn’t want to talk about herself. She would invariably respond to interviewers’ questions: “Who am I? I’m just a person, why are you so interested in me? I’m not so important.” She even raised a question in an interview with Eileen McDonald:

“I was only an ordinary member of the PFLP. He [Superintendent David Frew] insisted, ‘No you are not. Three days after your capture, the PFLP hijacked a British plane. They flew it to Dawson’s field, and they are now demanding your release for the passengers. Now do you understand you are very important?’”

According to McDonald, “Leila had been overwhelmed at the news; as she commented with a faraway look in her eyes, ‘A plane has been hijacked just for me’” which implies that she did not view herself as an important person.

Here again, Khaled is constructed as someone full of contradictions, who follows “her masters” and did not know what she was doing, or who was able to escape her patriarchal society that was so restrictive. Whether she was duped or independent, these accounts do not provide a clue.

As we know from women’s studies, encouraging students to be motivated and speak up is a basic staple of our calling. Voice, then, becomes a most important element of, and possibly a first step toward, liberation while silence is seen as a sign of submission and subservience. But could there be another explanation? Is it possible that what Khaled was doing was a way to deflect individualism, self-centeredness, and to refrain from self-promotion or placing herself on a higher plane than other folks — a conduct much praised in Palestinian cultural practices?

Is it possible that this member of the Central Committee of one of the major Palestinian factions was just saying, I am like everyone else, I just happen to be right now at the right place. This is the assignment that I volunteered for. I carried it out and that’s all there is to it? Isn’t it possible that Khaled sought to display humility, not self-deprecation?

Were we to take the context into consideration, the answer to this question becomes readily available. In a context that highly values individualism, Khaled may sound as if she were putting herself down. But looking at Khaled in her own environment in which people rarely use the “I” word, or cause listeners to cringe when they do, signifying that it is an inappropriate, or unbecoming behavior, we could begin to see Khaled’s words in a totally different light.

Imposing an analysis of one context onto a different one without accounting for the differences between them is not only highly problematic; it has serious implications for the study of revolutionary movements and for resistance studies.

Everyday Women’s Resistance

The role of women in the struggle was not limited to a few well-known daring exploits such as Leila Khaled’s. I remember my mother and her activist friends passing around underground petitions. While nothing about these petitions should have been considered “illegal,” given that they were simply signed by hundreds of Palestinian and directed at the United Nations, they were considered underground activities because they were banned by the Israeli military.

I remember my mother’s friends coming around and my mother saying, “shh, keep your voices down. The kids are sleeping.” They would speak softly while passing the petitions around, “So and so has to go there,” and “So and so needs to do this.” We learned at an early age of the need to be discreet, and the necessity not to say things out loud or reveal this information in public. As children living under occupation, we were constantly scared and had to always be careful.

I also remember my mother and her friends organizing sit-ins at neighborhood homes that were to be demolished by the Israelis. I used to sometimes accompany my mother and her friends to sit-ins if I were allowed. I remember them carrying out hunger strikes either at the neighborhood mosque or a church but mostly at the offices of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The hunger strikes were in solidarity with prisoners on hunger strike, against the takeover of land by Jewish settlers, or to protest other Israeli violations of Palestinian rights.

In this context, then, the politics of location and situated knowledge are essential to understanding women’s (and men’s) activism and the diversity in experiences and lives. Notions of universality, while wonderful in their idealism, do not always reflect grounded reality.

The feminist mantra of Virginia Woolf that “My country is the whole world” is an appropriate statement for women living at the heart of empire, whose countries colonize the rest of the world. That there should be no boundaries constructed to exclude those whom we deem unlike us, is correct and so is the implicit notion in Woolf’s statement that we need to struggle against this xenophobia and chauvinism that is permeating the environment today.

Yet colonized people and communities under siege do need boundaries, not in order to exclude others, but to protect themselves in semi-safe spaces where the hands of the colonizers do not reach. It is in spaces of this sort that the oppressed draw strength and to where they seek refuge when they flee. Those who have no country, such as the Palestinians, do not have the luxury to join Woolf!

Conclusion

This account has given a glimpse of the 1960s by placing the Palestinian anti-colonial struggle against Israeli colonization at the center of its analysis. I have drawn on the experiences of Palestinian women militants to argue that the 1960s narrative(s) must be contextualized and historicized as a corrective against applying the U.S. white heterosexual male narrative universally to all other areas and peoples.

My discussion of Palestinian women’s experiences suggests a different reading than that offered by Sara Evans regarding the U.S. women’s movement. In particular, I argue that consciousness is not necessarily sequentially ordered as Evans suggests. While such an explanation should not be excluded, a more plausible one, based on my research and experience, is that consciousness of gender inequality (or any other structural inequality or injustice) can supersede, accompany, or result from awareness of other systemic oppression.

In other words, as there are many sources of oppression, there are many paths to consciousness and liberation. Women who participate in anti-colonial movements are not duped, as colonial feminists claim. From the Algerian Jameelat to Leila Khaled, and from the Palestinian women militants to ordinary mothers, teachers and activists under occupation, the decision to participate in resisting colonialism is rational, conscious and pro-active. And it should be so: How else can justice prevail?

References and Selected Readings

Abdulhadi, Rabab. Revising Narratives: Gender, Nation and Resistance in Palestine (forthcoming).

De Beauvoir, Simone, & Halimi, Giselle. 1962. Djamila Boupacha. London: Cox and Wyman Ltd.

Frank H. Epp. 1976. The Palestinians, Portrait of a People in Conflict. Herald Press.

Sara Evans. 1980. Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left. New York: Vintage Books.

Fanon, Frantz. 1961. The Wretched of the Earth, New York: Grove Press, Inc.

—————– 1965. A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove Press, Inc.

Khaled, L. 1973. My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary. Edited by George Hajjar. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

MacDonald, Eileen. 1991. Shoot the Women First. New York: Random House.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

James Scott. 1987. Weapons of the Weak. New Haven: Yale University Press.

————– 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

The People’s Press Palestine Book Project, 1981. Our Roots are Still Alive: The Story of the Palestinian People. Institute for Independent Social Journalism.

Thornhill, T. 1992. Making Women Talk: The Interrogation of Palestinian Women. London: Lawyers for Palestinian Human Rights.

Viner, Katherine. 2001. “Beauty and the Bullets: What Became of Leila Khaled, the World’s Most Famous Terrorist Pin-Up?” The Guardian, Friday, January 26.

Warnock, K., 1990. Land Before Honor: Palestinian Women in the Occupied Territories. New York: Monthly Review Press.

For examples of what the author characterizes as “colonial feminism,” see for example:

Alvanou, Maria. 2004. “Hijab of Blood: The Role of Islam in Female Palestinian Terrorism.” ERCES Online Quarterly Review, 2004, 1, 3, Sept-Oct.

Andriolo, Karin. 2002. “Murder by Suicide: Episodes from Muslim History.” In Focus: September 11, 2001. American Anthropologist, Vol. 104, No. 3, September, 2002: 736-742.

Dworkin, Andrea. 2002. “Women Suicide Bombers.” www.Feminista.com/archives/v5nI/dworkin.html.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. “A New Counterterrorism Strategy: Feminism.” Alternet. 22 August 2005. http://www.alternet.org/story/21973/.

Morgan, Robin. 2001. The Demon Lover: The Roots of Terrorism, New York City: Washington Square Press.

Peck, Arlene. “Arab Women and Farm Animals.” www.sullivan-county.com/id4/peck2b.htm, 6 February 2004.

Smeal, Eleanor. “Special Message from the Feminist Majority on The Taliban, Osama bin Laden, and Afghan Women.” Available on the Feminist Majority website at: http://www.feminist.org/news/pressstory.asp?id=5802.

Victor, Barbara. 2003. Army of Roses: Inside the World of Palestinian Women Suicide Bombers. Rodale.

July/August 2012, ATC 159