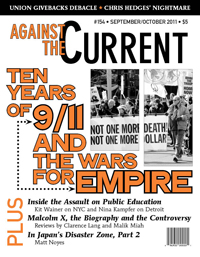

Against the Current, No. 154, September/October 2011

-

The Years of 9/11

— The Editors -

9/11 and the Clash of Atrocities

— John O'Connor -

Ten Years Later: We're Less Free

— Julie Hurwitz -

On 9/11 and the Politics of Language

— an interview with Martin Espada -

Alabanza: In Praise of Local 100

— Martin Espada -

To Rebuild Teamster Power

— an interview with Sandy Pope -

Bloomberg and NYC's Education Wars

— Kit Adam Wainer -

Detroit Public Schools: Who's Failing?

— Nina Kampfer -

The Catherine Ferguson Struggle

— Nina Kampfer -

Givebacks in a Deepening Crisis

— Jack Rasmus -

Letter from Tokyo: In "The Zone" of Disaster

— Matt Noyes - On Marable's Malcolm X

-

Manning Marable and Malcolm X: The Power of Biography

— Clarence Lang -

Evolution not "Reinvention": Manning Marable's Malcolm X

— Malik Miah - Reviews

-

Exploring Imperial Pathologies

— Allen Ruff -

Introduction to Is There a Human Future?

— David Finkel -

Chris Hedges' Vision & Nightmare: Is There a Human Future?

— Richard Lichtman -

The Fate of Vietnam's First Revolution

— Simon Pirani -

Bolshevism, Gender & 21st Century Revolution

— Ron Lare - In Memoriam

-

David Blair, Detroit Poet, 1967-2011

— Kim D. Hunter

Clarence Lang

Malcolm X:

A Life of Reinvention

by Manning Marable

New York: Viking, 2011, 594 pages, $30 hardback.

SOCIAL MOVEMENT THEORISTS have written much about the political opportunities, constraints, and levels of organizational readiness enabling or inhibiting popular insurgency.(1) We still know less, however, about the complex framing processes involved in forging and maintaining activist identities and self-narratives.

From this standpoint, Manning Marable’s posthumously published Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention is an important endeavor in historical and political biography, though ultimately — despite its nearly 600 pages — it is not a transformative work on its subject, or within the genre. Its publication provides an opportunity to not only evaluate the book and rethink The Autobiography of Malcolm X, but also to reassess Malcolm’s continuing relevance among scholars and activists. Moreover, it allows for a meditation on the impact of Marable (1950-2011) as an influential Black intellectual-activist himself.

I first met Dr. Marable in the early 1990s when I was an undergraduate majoring in journalism at the University of Missouri at Columbia. Like many African-American youth of high-school age in the late 1980s, I had been influenced by the period’s Black Nationalist resurgence — itself a reaction to Black America’s declining quality of life under Reaganism.

The airing of the PBS documentary series “Eyes on the Prize” had been a critical consciousness-raising event for large numbers of us, and the rhetoric and symbols of the 1960s Black Liberation Movement infused the hip-hop music popular at the time — artists such as Public Enemy, Queen Latifah, X Clan, Brand Nubian, and Poor Righteous Teachers. Of all the words and images, those of Malcolm X (Malik Shabazz) were the most pervasive and potent, leading many of us directly to his Autobiography.

Marable the Scholar-Activist

Our discovery of previous eras of African-American struggle, and in particular our introduction to Malcolm as a figure of uncompromising Black heroism, had primed us for the culture wars over affirmative action and multiculturalism that awaited us at the nation’s university and college campuses. Missouri, a bellwether state, was the home of Rush Limbaugh, whose national stature as a right-wing pundit was growing and whose show was wildly popular on campus. Here, I learned that Malcolm was the touchstone for different political trends, claimed by Trotskyists, orthodox Muslims, conservative Republicans, liberal Democrats and Black Nationalists alike.

The University of Missouri’s Black Studies Program and Black Culture Center were led by veterans of revolutionary nationalist and Marxist organizations, and their sponsorship of a speaking engagement by Marable reflected this orientation. Invited to write an article on Marable for the Black Studies newsletter, I sat with him for a lengthy conversation. Regrettably, I never published the interview, but I left that meeting with a heady sense of possibility.

To someone searching for a clearer understanding of racial and economic inequalities, Marable’s attention to political economy, and the manner in which he wedded his anti-racism to a critique of capitalism, was a powerful rebuke to conservative arguments from the right — and, I believed, a compelling alternative to Afrocentrism, then the dominant Black Studies paradigm nationally. I quickly immersed myself in his work, which had a radicalizing effect. Marable’s How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America and From the Grassroots: Essays Toward Afro-American Liberation, as well as his syndicated column in the Black press, “Along the Color Line,” fed my growing involvement in campus politics.

The legitimacy of mature left perspectives like Marable’s were driven home as I directly encountered, through an intense but short period of student activism, the racism and cynicism of white student government, the complicity and indifference of university administrators, the obstructionism of student services staff, and the conflicting interests among Black student leaders (many of whom regarded Black student organizations mainly as a professional credential).

These experiences, along with Marable’s work, not only helped to deepen my understanding of social inequality and how it is politically, ideologically and coercively maintained, but it also challenged any approach to Black Nationalism based on simplistic ideas of racial unity. Such exposure to the power of study and struggle shaped my desire to pursue a life of scholarship and activism beyond my undergraduate career.

In graduate school, I continued to follow Marable’s career, which eventually led him to Columbia University, the founding of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies, and prominence as a voice of the Black left. His Race, Reform, and Rebellion, now in its third revised edition, profoundly influenced my approach to interpreting the history of post-World War II Black social movements; I still consider it the best general synthesis work on the Black Liberation Movement between the 1940s and contemporary times.

Similarly, the debate concerning the emergence of Black celebrity intellectuals, which Marable and political scientist Adolph Reed waged on the pages of the journal New Politics in the late 1990s, was an acrimonious yet timely exchange that forced many of us working toward our M.A.’s and doctorates to think more critically about the contemporary phenomenon of Black public intellectuals, and our own roles and duties as budding Black Studies professionals.

Reed’s main point had a sharp ring of truth: High-profile Black scholars such as Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Cornel West postured as heirs to the scholar-activist tradition of W.E.B. DuBois, but unlike DuBois they lacked accountability to any clear Black communities or constituencies, were disconnected from real political engagement, and existed largely as freelance race spokespersons who interpreted Black America to elite white audiences. I was moved more by Reed’s arguments than by Marable’s objections that Reed had lumped together a diverse group of scholars, overstated his criticisms of scholars who actually shared his values, confused his allies with enemies of the left, and ignored the greater danger to Black welfare posed by ideologues of the right.(2)

Given the fundamental questions the entire controversy raised about the responsibilities and crises of Black intellectuals in an era of conservative retrenchment and hegemony, and the need for coordinated progressive mobilization on the ground, I suspect that the exchange had a bearing on Marable’s role in convening the Black Radical Congress (BRC) in 1997-98, especially considering the group’s formation soon after the Reed-Marable match.

We were reacquainted during my own involvement in the BRC, where we ended up on opposite sides of a number of important debates regarding strategy and vision. This included the matter of accepting a grant from a major private foundation whose corporate liberal cooptation of the movement in the late 1960s had been revealed in Robert L. Allen’s classic Black Awakening in Capitalist America. But it was impossible to dispute Marable’s dedication to progressive social change, and unlike many of his colleagues castigated by Reed, he participated meaningfully in the tedious, mundane work of this national coalition of progressive activists, organizers and intellectuals.

Indeed, Marable remained politically consistent even as Reed largely dismissed Black Liberation activism as hopeless, opposed the campaign for reparations, and even rejected the idea of a “Black community.” After my participation in the BRC ended, and as my own career in academia progressed, Marable and I maintained cordial though very infrequent email correspondence, though I later had the privilege of publishing a book in a series of which he served as co-editor.(3)

Reinventing Malcolm

Marable’s faith in study and struggle, his participation in Black united front efforts, his belief in institution building, his visibility as a counterhegemonic intellectual, his advocacy of social democracy at home and opposition to U.S. militarism abroad, and his wide-ranging effect on a generation of students attracted to radical thought, all revealed a desire to follow not only in the footsteps of DuBois (an obvious inspiration) but also Malcolm X. Marable’s massive, briskly paced and highly readable Malcolm X, then, seems a fitting coda to a remarkable career.

Given the voluminous literature on Malcolm that already exists, the general outlines of his life history are widely known — his Garveyite parentage, Midwestern upbringing as Malcolm Little, criminal exploits as “Detroit Red,” prison conversion to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam (NOI), ascendance as minister of Harlem’s Mosque No. 7 and national spokesman, evolving tendencies toward secular Black freedom struggle, the mounting political tensions and mistrust that strained his relationships with Muhammad and the NOI’s central leadership, the eventual split, his international travels and search for a new political and organizational identity, and the meeting at the Audubon Ballroom where executioners gunned him down.

So why the need for another book? “Many Malcolmites had constructed a mythic legend to surround their leader that erased all blemishes and any mistakes he had made,” Marable states. “Another version of ‘Malcolmology’ simplistically equated Martin Luther King, Jr., with Malcolm, both advocating multicultural harmony and universal understanding.” Lost in both versions has been the “[t]he historical Malcolm, the man with all his strengths and flaws.” (490)

Comprehending Malcolm’s interior life, and how it molded him, depends on a critical reinterpretation of his Autobiography as “more of a memoir than a factual and objective reconstruction of a man’s life,” Marable maintains. (491) “How much isn’t true, and how much hasn’t been told?” he queries. (10) Foremost, Malcolm’s narrative was not an individual act of self-creation, but rather a collaboration with Alex Haley, a liberal Republican and unabashed integrationist who, following Malcolm’s death, became the narrative’s main interpreter.

Financially insecure and eager for a book that would appeal to a mass (i.e., white) audience, Haley steered the Autobiography away from exploring Malcolm’s Black Nationalist philosophy after his departure from the NOI, and suppressed any exploration of his fledgling Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU).

Marable’s larger point is that the Autobiography is significant precisely because of Malcolm’s omissions and exaggerations. It brings into sharp focus what the author regards as Malcolm’s greatest asset: “his ability to reinvent himself, in order to function and even thrive in a wide variety of environments” and reach the most economically exploited and socially marginalized segments of Black urban communities. (479)

Adept at donning different guises that shielded his inner self from others, “Malcolm drew generously from his background, so that over time the distance between actual events and the public telling of them widened,” he argues. (10) “In this sense, his narrative is a brilliant series of reinventions, ‘Malcolm X’ being just the best known.” In this respect, Malcolm was like other public figures who, molded by the events of their time, have selectively refashioned their pasts for political effect.

The author devotes himself to disputing major claims made in the Autobiography. Contrary to Malcolm’s account, for instance, “Detroit Red” was an amateurish criminal. He magnified his exploits to make more dramatic his transformation under Muhammad’s tutelage.

Coming at a time when his close ties to the NOI leader were beginning to unravel, Malcolm “also hoped that the narrative would stand as a testament to his continued devotion to and adoration of the Messenger.” (260) To deflect mounting criticism that he “coveted the Messenger’s position, that he craved material possessions, and that he was using the Nation to advance himself politically and in the media,” Malcolm actively encouraged a cult of personality around Muhammad, a strategy he later regretted. (198)

Along these lines, Malcolm X provides a vivid sense of the internal workings of, and intrigue within, the Nation of Islam. As described by Marable, Malcolm’s doubts about Muhammad’s leadership, and the NOI cosmology, began earlier than described in the Autobiography — as early as 1959 during his first travels abroad.

Frustrated by the organization’s passivity in the fact of rising Black freedom militancy, and humiliated by the NOI’s inaction after police violently raided the Los Angeles mosque, “Malcolm knew that the Nation’s future growth depended on its being immersed in the Black community’s struggles of daily existence.” (129) Drawing upon his experiences working with Black elected officials, labor leaders, political radicals, and intellectuals in Harlem, he envisioned the NOI engaging in united front politics at a national and international scale.

Given the previous publication of William Sales, Jr.’s From Civil Rights to Black Liberation: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity, which covers similar ground in this regard, Marable does not break substantively new ground in exposing the “deeper ideological and political differences that increasingly divided Malcolm from the Nation” as he grew more skeptical of its theology and distance from movement-oriented engagement. (491)

Yet Marable does skillfully show that Malcolm did not unwittingly violate Muhammad’s prohibitions against secular politics, which diverges from standard depictions of Malcolm’s innocent zeal for action leading him away from NOI orthodoxy. To the contrary, Malcolm subtly at first, then more openly, challenged Muhammad in charting an activist direction for the NOI. His tragic mistake, however, “was believing that his militant political aims — the creation of an all-inclusive Black united front against U.S. racism — could be constructed with the full participation of the Nation of Islam,” whose leadership was ambivalent about the civil rights demonstrations, Third World revolution, and Pan-Africanism that increasingly claimed Malcolm’s attention. (284)

This realization, and disenchantment over Muhammad’s indiscretions, the decadence of NOI’s Chicago headquarters, and his embrace of orthodox Islam, presaged his formation of Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI) and the OAAU. Their emergence, though, intensified a climate of fear, surveillance and repression that made his death all the more likely.

The Flawed “Historical Malcolm”

Marable also spends a great deal of time recounting the disorganization within, and class-based conflict between, members of the OAAU and MMI. Antagonistic toward members of the Black middle class from a young age, Malcolm nonetheless recruited petty bourgeois intellectuals, professionals, and celebrities to help establish the OAAU.

Although this may have been a logical move in creating the united front that he envisioned, the author notes that it disoriented and alienated many old supporters (many hailing from the working class) who had risked their lives following him out of the NOI. And while he spends a great deal of time outlining the intellectual development of Black Nationalism, Islam and their moments of convergence, Marable offers little description and analysis of the platforms and intellectual life of either the OAAU or MMI. This would have offered more concrete context for understanding the complicated fusion of Black Nationalist ideology, Muslim wordview, global framing, and liberal-integrationist strategies of mass direct action and militant self-defense he was struggling to achieve.

Marable fares much better discussing the uncertainties that dogged Malcolm as he “alternated between reaffirming his loyalty to Elijah Muhammad’s ideas and decrying his flawed morality, sometimes in speeches only days apart.” (297) This manifested more broadly the “different tones and attitudes” Malcolm took, “depending on which group he was speaking to” in the last period of his life. (405)

Marable not only captures the heady environment in which Malcolm grasped for a new political trajectory, but also the contingency of events that unfolded around him, particularly those developments that Malcolm, in the there and then, was unable or unwilling to grasp. He only gradually perceived the lengths to which his opponents in the NOI were willing to go to remove him, and held onto the possibility to being reinstated in the NOI even as officials in New York and Chicago determined that his death was a necessity.

Marable vividly captures how, in the chaotic months leading up to his assassination, Malcolm’s behavior — sometimes defiant, at other moments fatalistic — seemed intent on provoking retaliation: “[T]he convergence of interests between law enforcement, national security institutions, and the Nation of Islam undoubtedly made Malcolm’s murder easier to carry out.” (424) Nonetheless, he clearly suggests that the assassination was not inevitable, and that Malcolm might have been able to avoid this fate had he and his OAAU-MMI associates made more careful strategic decisions, including those related to his personal safety.

There were other major lapses in Malcolm’s judgment, including his negotiations on the NOI’s behalf with leaders of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party, uncritical praise of Kwame Nkrumah and other heads of state in post-independence Africa, and bizarre support for Barry Goldwater in the 1964 U.S. presidential election, the latter of which Marable does not go to any length in explaining.

Malcolm was, moreover, a rigid disciplinarian of his rank and file and a demanding general of his closest lieutenants, whose loyalty he at times abused. But he pushed himself even harder, and many readers will be exhausted by passages documenting the relentlessness with which Malcolm worked to expand the numbers of NOI mosques, recruit members, spread Muhammad’s teachings, consolidate the OAAU, and knit a web of internationalist alliances.

A Steep Price

According to Marable, Malcolm’s family paid a steep price for these achievements, notwithstanding the fact that given the conventions of the time, he provided them a stable household. Moreover, while he relied on the strength, skill and support of his sister Ella Collins (a prominent figure in this life history) and associates such as Shirley Graham DuBois, Maya Angelou and Lynne Carol Shifflett, he was deeply distrustful of women overall.

The author underscores Malcolm’s misogyny in his treatment of his marriage to Betty Shabazz, implicitly drawing tight the connection between the personal and the political. Taking a wife largely because his ministry required it, he vacillated between genuine warmth and emotional coldness in their partnership. Given to “disappearing whenever a new baby appeared” (379), he often left Betty to bear the brunt of the family’s financial insecurity and, as Malcolm’s relationship with the NOI rapidly deteriorated, humiliation and intimidation.

Marable drives this point home most forcefully when he chronicles how, in the freezing cold after arsonists had just firebombed their home, Betty learned that Malcolm was still planning to keep a speaking engagement in Detroit that day. Marable mostly avoids judgment when recounting such episodes, though he states that Malcolm increasingly “viewed his wife largely as a nuisance — someone he was obliged to put up with — rather than as a loving life partner.” (164)

This estrangement accompanied a dysfunctional sex life, which the author suggests may have led both of them to infidelity. To be sure, Betty emerges in Marable’s biography as a complex and tragic figure in her own right, and a case study of both the advantages and perils of patriarchal protection. Influential in Mosque No. 7 due to her marriage to Malcolm, she was simultaneously a beneficiary of power and a subject of scrutiny and derision. Suspicious of the NOI leadership earlier than Malcolm, Betty did not submit easily to the rituals of obedience demanded by her husband and the NOI hierarchy, yet her structural relationship to both was one of subordination.

Marable narrates the messy features of interior lives that condition involvement and efficacy in movements, though he does not actively theorize them. That Malcolm brought the matter of his sex life to Muhammad for instruction; and that Malcolm’s enemies highlighted Betty’s assertive personality and seized upon rumors of her unfulfilled sexual demands to politically undermine him, show how central the patriarchal family was deemed to the exercise of public power and manly respectability.

Nor does Marable interrogate Malcolm’s changing attitudes toward women and gender, leaving the impression that his views on the issue remained static — very different from his approach to other aspects of Malcolm’s thought. Still, he provides ample background for others to explore more conceptually. As historians such as Farah Jasmine Griffin have maintained, scholars of Black culture and Black freedom movements need to pay more serious attention to the politics of sexuality as well as gender in their narratives.(4)

Controversies and Methods

Betty and Malcolm’s intimacies and indiscretions are only part of the revelations in this book that have drawn controversy within Black Studies circles since the book’s publication in April. Marable speculates that as a young hustler, Malcolm may have had paid sexual encounters with a wealthy white man, a relationship that he attributed in the Autobiography to the fictitious “Rudy.”

The author covers this far less extensively and salaciously than Bruce Perry’s 1992 Malcolm: The Life of the Man Who Changed Black America. In fact, it occupies very little space in Marable’s work, and in the final analysis does not amount to much; one can read its inclusion as simply consistent with Marable’s overall thesis about the overall silences in Malcolm’s self-presentation. All the same, this detail has been at the center of fervent criticism by several activist-intellectuals, who view the claim as symptomatic of a larger problem with the work: Marable often overreaches his evidence, does not rely enough on primary documents, and draws too many conclusions from inferences and speculation.(5)

Given that Marable marshals a variety of sources, including published accounts, first-person interviews, and government documents and other primary evidence, it would be inaccurate to call him a careless researcher. Yet these criticisms raise important points about historical research methods. If primary materials are readily available, shouldn’t the historian — especially one who possessed as many resources as Marable — be expected to privilege their usage, wherever possible, over second-hand reports?

By the same token, historians often make inferences beyond archival material and secondary work in order to get at the thoughts of historical actors and the meaning of their actions. Marable acted no differently in this regard. Historians’ findings are often provisional, leaving them subject to revision. This is fine as long as they qualify their claims in such circumstances, and draw conclusions reasonably and responsibly.

But how do we judge “reason” and “responsibility” in these instances? This is the nub of the problem. Marable’s conclusion that the Central Intelligence Agency had a hand in Malcolm’s food poisoning while abroad, for instance, derives from the same historical method that characterizes his discussion of Malcolm’s activities as a hustler. Yet the former is one among similar inferential conclusions that Marable’s detractors are uninterested in disputing.

Criticisms of Marable’s use and interpretation of sources sidestep the real basis of anxiety surrounding his claims about Malcolm’s possible same-sex trysts. Several decades after his death, Malcolm is a reliable condensation symbol of Black manhood, the Black family, and the Black Liberation Movement. For some, if Marable’s conclusions about Malcolm’s sexual past are true, they would have no real meaning other than what columnist Irene Monroe characterizes as “the art and survivalism of street hustling culture,” in which “Detroit Red” was immersed. For others, Marable’s claim amounts to the emasculation of a revered warrior of Black freedom.

Even among scholars who appreciate the imperative of critical, revisionist history, the idea that Malcolm may have been “gay for pay” during his lumpen phase, harbored a deep-rooted animosity toward women or was an inadequate lover to his wife, brings to the surface a strong investment in preserving him as an icon of uncompromising Black resistance and guardianship — which for many of us rests implicitly on his heteronormative masculinity, virility and healthy regard for Black women.(6)

Perhaps the more explosive claim in this biography is that two of the men arrested and convicted of Malcolm’s murder were completely innocent. Marable contends that the Federal Bureau of Investigation and New York police, both of which kept Malcolm under surveillance, possessed advance knowledge of plans to kill him, and after it occurred concerned themselves more with protecting informants and undercover agents than in arresting the true culprits.

He argues that the real assassins, dispatched from the NOI’s Newark mosque, not only escaped detection, but in the case of the individual who allegedly fired the fatal shotgun blast, also became a respected local community figure. With the reopening of several civil rights “cold cases” over the past decade, it will be worthwhile to see where the author’s allegations lead, if anywhere. Considering the multiple layers of people and institutions that stood to gain from Malcolm’s death, justice is not a likely outcome.

Conflicting Assessments

Earlier works, notably Karl Evanzz’s The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X, also have offered theories about the assassination. This speaks to a key weakness of Marable’s book, which is that he does not engage any of the existing bodies of literature on Malcolm. This absence of historiography may have stemmed from editorial decisions about how to best make the biography accessible to general readers, but it exposes him to the legitimate complaint that he does not acknowledge all of his intellectual debts. It also creates difficulty in determining how to locate his book in the current scholarship or evaluate any original claims.

Then, too, there is a nagging question: If his argument is both that Malcolm reinvented himself in the Autobiography and that Haley had the final say in representing Malcolm in this work, who is primarily responsible for its distortions? While rightfully objecting to Malcolm’s cooptation by Haley and others, Marable also seems to recast Malcolm in his own image — in this case as a radical democratic humanist veering away from Black Nationalism toward the belief that African Americans could improve their conditions through reform of the existing U.S. system.

This is a surprising conclusion, given Marable’s own narrative of Malcolm’s deepening revolutionary praxis, and his explicit rejection of Malcolm’s popular usage as a symbol of multicultural inclusion. It minimizes Malcolm’s developing relationships with the Revolutionary Action Movement and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee – one of which manifested a clear Black (inter)nationalism, with the other quickly moving in this direction. It also subtly casts Black Nationalism in a reactionary light, distorting a diverse tradition that has included the “multiethnic and interfaith coalitions” that Marable contends were crucial to the last phase of Malcolm’s life. (485)

Ultimately, what do we gain from Marable’s closer interrogation of Malcolm X’s inner life and tremendous capacity for self-transformation? Is it to illustrate how his many incarnations mirrored the dramatic metamorphoses among African Americans’ lives and conditions in the 20th century? Others have done this already. How is Malcolm consequential now? Marable answers this by situating him within global Islam today, and distancing him from the strain of anti-Americanism that resulted in the 2001 September 11 attacks. (Most likely because the book was in production at the time of the democratic upsurge that ousted President Hosni Mubarak, Marable does not comment on the momentous events in Egypt this past spring.)

“Given the election of Barack Obama, it now raises the question of whether Blacks have a separate political destiny from their white fellow citizens,” he argues more tentatively. “If legal racial segregation was permanently in America’s past, Malcolm’s vision today would have to radically redefine self-determination and the meaning of Black power in a political environment that appeared to many to be ‘post-racial.’” (486)

This is an unclear statement about Malcolm’s relationship to contemporary “color blind” discourses, leading one critic to exaggeratedly accuse Marable of “dragging Malcolm to Obamaland.” With many left, progressive and even liberal commentators still reeling from the president’s capitulation to the Tea Party right in the recent debt ceiling “crisis,” this passage is a terribly missed opportunity on Marable’s part for greater elaboration about Malcolm’s legacies in light of the Obama phenomenon.(7)

Finally, while he argues that Minister Louis Farrakhan was “[t]he chief beneficiary of Malcolm’s assassination” (476), Marable says remarkably little about the path of Farrakhan’s ministry, especially in the 1980s and 1990s when Malcolm’s former protégé was at the apex of his influence as a national spokesman for Black America. The absence of discussion of the historic 1995 Million Man March is glaring: The event was an impetus for Marable and others to convene the BRC, which reflected an alternative imagining of Malcolm’s lineage.

What are the ideological, political and historical contexts that distinguish Malcolm’s “Message to the Grassroots” from Farrakhan’s equally memorable message of “atonement” and reconciliation several decades later? What lessons can scholars and activists draw from the shifting political landscape that shaped Malcolm in the period of the 1960s, and that shaped Farrakhan in its aftermath?(8)

Confronting Our Responsibilities

Autobiography often melds truth and fiction. But biography is also an ethically open-ended process that hands the writer power to represent people unable to represent themselves. Marable surely was aware of the enormous liabilities he assumed in beginning this labor of love. His passing is all the more tragic because it has deprived us of his response to critics and the chance to allow him to grapple with the implications of this work. Malcolm X does not stand singularly among the work published about Malcolm since the 1990s, but it is worthy of wide readership and continuing debate.

In impact, if not by intent, the book sets a stage for ongoing conversation about the importance of historical biography to social movement theory. Beyond the accumulation of collective grievances, the terrain of objective historical conditions, and the readiness of communal institutions, how are individual and group identities created and mobilized for prolonged movements? More to the point, how are existent relationships — public and private, civic and familial — revised and placed in the service of emancipatory goals? How do movement participants manage their dense, multiple and simultaneous bases of belonging, and what are the outcomes when they fail to bridge these affinities?

Malcolm emerges as a case study of how interior life histories can illuminate and enrich narratives of Black freedom struggle. Many of us in Black Studies were attracted to the discipline by the icon of Malcolm and, as discussed above, the circumstances of our own life histories. Similarly, the current historical juncture requires those of us who study the Black experience to fundamentally reassess who we are and why we do what we do.

We are confronted with the tangled contradictions of catastrophic Black unemployment and a widening racial wealth gap; the mainstreaming of fringe-right racism and social policy; structural adjustment imposed on the U.S. populace by conservative Republicans and credit rating agencies at the behest of financial capital; and popular entreaties from the Reverend Al Sharpton, the host of the nationally syndicated “Tom Joyner Morning Show,” and others to support the nation’s first Black president in the interests of racial solidarity, even as he and the leaders of his party shrink from liberal reform.

Black Studies practitioners have no special entitlement to leadership by virtue of expertise, but if ever a time existed for renewed political imagination and initiative on the part of Black activist-intellectuals, now is one of those times. It is not entirely clear what such initiatives might be, but our training certainly demands more of us than just writing, teaching, and service to academic and professional institutions.

However imperfect Marable’s biography may be, the conversations it has sparked raise pertinent questions about future directions in the field of Black Freedom Studies, the state of Black Studies, and the health of the Black intellectual-activist tradition — conversations in which Marable was involved throughout a prodigious career. The current discourse about his work is, among other things, a tribute to an individual whose own history of intellectual activity and political engagement helped draw many of my peers and me to his work, our higher level of political consciousness and scholarly professions, and our own sense of social responsibility beyond the confines of the academy.

Notes

- For an influential work in this field, see Doug McAdam, Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970, second edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

back to text - Adolph Reed, “What Are the Drums Saying, Booker? The Current Crisis of the Black Intellectual, The Village Voice, April 11, 1995, 31-36; Manning Marable, “Black Intellectuals in Conflict,” New Politics, Vol. 5, No. 3 (Summer 1995): 35-40; Reed, “Protect the Legacy of Debate,” and Marable, “Manning Marable Responds,” New Politics, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Winter 1996): 60-63, 63-66; and Reed, “Rejoinder to Marable: On Black Intellectuals,” and Marable, “Manning Marable Replies,” New Politics, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Summer 1996): 22-27, 28.

back to text - Jennifer Hamer and Clarence Lang. “Black Radicalism, Reinvented: The Promise of the Black Radical Congress,” in Herb Boyd, ed., Race and Resistance: African Americans in the 21st Century (Boston: South End Press, 2002), 109-136; Adolph L. Reed, Class Notes: Posing as Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene (New York: The New Press, 2001); and Reed, “The Case Against Reparations,” The Progressive (December 2000): 15-17.

back to text - Farah Jasmine Griffin, “‘Ironies of the Saint’: Malcolm X, Black Women, and the Price of Protection,” in Bettye Collier-Thomas and V.P Franklin, eds., Sisters in the Struggle: African American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement (New York University Press, 2001), 214-229.

back to text - For a few examples of such commentary, see Karl Evanzz, “Paper Tiger: Manning Marable’s Poison Pen,” Truth Continuum, April 13, 2011, http://mxmission.blogspot.com/2011/04/paper-tiger-manning-marables-poison-pen.html; Amiri Baraka, “Amiri Baraka on Marable’s Malcolm X,” TheBlackList Pub, May 10, 2011, http://theBlacklistpub.ning.com/profiles/blogs/amiri-baraka-reviews-manning; and Abdul Alkalimat, “Rethinking Malcolm Means First Learning How to Think: What was Marable Thinking? And How?” June 2011, http://brothermalcolm.net/marable/pdf/alkalimat.pdf. For favorable reviews of the book, see Michael Dawson, “Marable’s Malcolm X Book Puts Icon in Context,” The Root, April 29, 2011, http://www.theroot.com/views/marables-malcolm-x-book-puts-icon-context; Salim Muwakkil, “Malcolm’s X-Factor,” In These Times, June 22, 2011, http://www.inthesetimes.com/article/11464/malcolms_x-factor/; and Bill Fletcher, Jr., “Manning Marable and the Malcolm X Biography Controversy: A Response to Critics,” The Black Commentator, July 7, 2011, http://www.Blackcommentator.com/434/434_aw_marable_marable_malcolm_controversy_share.html.

back to text - Irene Monroe, “Malcolm X Was ‘Gay-for-Pay,’ New Book Says,” The Huffington Post, April 7, 2011, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/irene-monroe/malcolm-x-was-gayforpay_b_845979.html.

back to text - Glen Ford, “Dragging Malcolm X to Obamaland,” Black Agenda Report, April 27, 2011, http://Blackagendareport.com/content/dragging-malcolm-x-obamaland.

back to text - Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua and Clarence Lang, “Providence, Patriarchy, Pathology: Louis Farrakhan’s Rise & Decline,” New Politics, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Winter 1997): 47-71.

back to text

September/October 2011, ATC 154