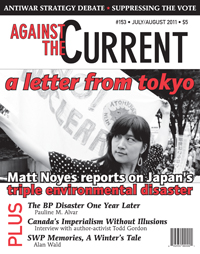

Against the Current, No. 153, July/August 2011

-

Austerity and U.S. Decline

— The Editors -

A Whiff of Jim Crow

— Malik Miah -

One Year of the BP Blowout

— Pauline M. Alvar -

Tokyo Letter: After the Disaster

— Matt Noyes -

What Did They Know...?

— Matt Noyes -

Canada's Imperialism Without Illusions

— ATC interviews Todd Gordon -

Brief Theory of the Present Crisis

— Hillel Ticktin -

Remembering the Paris Commune

— K. Mann -

Women in the Paris Commune

— Dianne Feeley -

A Winter's Tale Told in Memoirs

— Alan Wald -

Education Over Incarceration

— Luis Gonzalez - Dialogue

-

A Comment on Antiwar Strategy

— David Finkel -

A Rejoinder on Antiwar Strategy

— David Grosser - Reviews

-

Drugs, Race & the Gulag Industry

— James Kilgore -

Thinking About Equality

— Bill Smaldone -

The SEIU as Case Study

— David Cohen -

The Union in Academia

— Dan Clawson - In Memoriam

-

Leonard Irving Weinglass

— Michael Steven Smith -

Remembering Manning Marable

— Elizabeth Kai Hinton -

Gil Scott Heron

— Kim D. Hunter

Matt Noyes

They want us to believe

that none of this could have been foreseen

but the sky has a familiar feel,

like the itch of black rain.

It was all just a goddamn lie,

Now I feel like I’ve gotta do something.

—Saito Kazuyoshi, “Zutto Uso Datta”

(It was all just a lie.)

(Facebook status update) Friday March 11, 3:26pm: Everybody in our family fine, but things got a little shaky.(1)

JUST BEFORE 3PM on March 11th, I was standing in the intersection of two small streets in central Tokyo, saying goodbye to my partner before leaving for a work trip to the United States. Earthquakes are common in Japan, but we knew right away this one was different. The earth rumbled and rolled, shifting back and forth and around, the intensity rising and falling and rising again.

It was long enough for us to look around and talk with other people on the street. We held on to each other’s arms and crouched, ready to jump out of the way of the swaying telephone poles and the cinder block walls that rocked back and forth.

Tokyo sits near the intersection of three tectonic plates, making it one of the riskiest areas in one of the most earthquake-prone places on earth. People are accustomed to earthquakes here, but in the back of everyone’s mind is the massive earthquake that is long overdue to strike the Tokyo area. The big one is still to come. In our small postwar wooden house it’s easy to tell when there is an earthquake because the windows rattle and the lamps sway.(2)

When the shaking stopped we checked on the damage. Some fallen books, some picture frames, the small flat screen television tipped over, nothing serious, so I headed for the train station. My partner went to get our son at the free afterschool program at his elementary school nearby. They’ve done plenty of earthquake drills and the school was recently rebuilt.

A strong aftershock came when I was on the bus, rocking it back and forth. We continued on our way and as we passed an elementary school, I saw parents taking their children home, most wearing their shiny silver bosai zukin — the fireproof hoods issued to children since WWII.(3)

At the train station, I was met by a wave of people pouring down the stairs. The half dozen train lines that run through Shinagawa Station, including the bullet trains, were all shut down. Power was off. People were walking home. A station agent told me Narita airport was closed; the buses were packed so I walked home.

It reminded me of the morning of September 11th, 2001, crossing Flatbush Avenue on my way to work and running into the river of people walking home from lower Manhattan, some covered in dust, a huge plume of smoke stretching up and over Brooklyn.)

It wasn’t until I saw the television and got online that I realized the extent of the damage. The map of Japan was on TV with the East Coast lined with flashing thick red and yellow bars indicating continuing tsunami warnings. Every few minutes an earthquake warning would scroll across the top of the screen and an aftershock would rattle the house.

Television news focused on the tsunamis as they struck place after place, and more and more amateur video came in. It seemed people had to see it over and over just to grasp the enormity. Not wanting to traumatize our son, we didn’t keep the TV news on. Aftershocks kept coming as the earth below us adjusted in the wake of the earthquake.(4)

It took some time for the scale of the “3.11” earthquake and tsunamis to sink in. Entire villages were simply destroyed, including those behind huge seawalls built after tsunamis decades ago. Ports, factories, farms, schools and clinics were wiped out. So great was the shift in the earth’s plates that Japan’s main island moved several meters to the east and some coastal lands in Northeastern Japan are now below sea level.

Evacuation plans proved inadequate; in one tragic case teachers and the children they were leading to the designated evacuation center were caught on a bridge and swept away. The number of dead, injured and missing rose hour by hour. There are now 15,413 confirmed deaths, 8,069 remain missing, 88,361 in shelters, thousands more displaced — Japan’s worst disaster since WWII.(5)

Massive fires at oil refineries and the destruction of industrial facilities along the coast have had a tremendous economic and ecological impact, creating new hazards. The Tokyo Occupational Safety and Health Center is working to educate recovery workers about the dangers of exposure to asbestos and other hazardous materials and get them proper masks.(6) Reuters reports that Japan’s Economics Minister has put the cost of recovery and reconstruction at nearly $200 billion.(7)

The Big Fear

Just as we started to grasp the enormity of the disaster caused by the tsunamis, a whole new crisis loomed. The earthquake and tsunami had caused severe damage to reactors at TEPCO’s Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant.

There are two power plants at Fukushima: Daiichi (number one) which has four boiling water reactors (BWRs), and Daini which has two BWRs. The reactors, some as much as 40 years old, were made by GE, Toshiba and Hitachi. Most of the problems have been in the Daiichi facility, but the Daini reactors, which were not operating at the time of the earthquake, have suffered periodic losses of power and cooling and are flooded with contaminated water from Daiichi.(8)

Power was knocked out, connections were damaged, pumps and cooling systems failed, backup generators were flooded. With no cooling, temperatures rose rapidly in the reactors and spent fuel pools, water boiled off, hydrogen and oxygen in water molecules separated, and engineers desperately vented the resulting gases and steam into the atmosphere in an effort to avoid explosions.

The zirconium alloy cladding that surrounds the nuclear fuel in the rods began to oxidize and burn. Twenty-four hours after the tsunami hit, an explosion blew the upper walls and roof off of Reactor 1, the core of which was already melting down.

As workers at the utility company tried increasingly desperate measures to get water into the reactors and spent fuel pools, hydrogen explosions rocked reactors 3, 2 and 4, which also had a series of fires. By midweek, the cores of Reactors 1, 2 and 3 had melted down, the reactor pressure vessels had developed cracks and holes and were leaking radioactive water and perhaps fuel, and there was damage to the spent fuel stored in Reactors 2, 3 and 4.

Radioactive debris, including plutonium, had been blown miles away and fuel was “melting through” the containment. The reactors had released something like 40% of the total radiation released at Chernobyl and the crisis was ongoing. But we didn’t know all that at the time.

In our house in Tokyo, rattled by aftershocks, we tried to piece together different news accounts so we could figure out what was happening and what it meant for us. Could there be a meltdown? Were we safe? What should we do? What could we do?

March 14, 11:44am: A second hydrogen explosion at Fukushima [Reactor 3, 11:11am]. The pro-nuclear energy types [in internet news stories] say it’s not a threat unless the inner containers have been breached. Not good to see a big plume rising from a nuke plant, no matter how you slice it.

This is the explosion that nuclear engineer Arnie Gundersen believes to have been a hydrogen explosion followed by a “prompt, moderated, criticality” i.e. a sudden nuclear reaction. Gundersen’s video updates on www.fairewinds.com have been invaluable.

7:39pm: This would be the worst news of late [“In Stricken Fuel-cooling Pools, a Danger for the Longer Term,” NYT 3/15/11]: “Even as workers race to prevent meltdowns, concerns were growing that nearby pools holding spent fuel rods could pose an even greater danger.”

7:57pm: Utility workers and managers and safety workers/police are putting it all on the line at Fukushima. Rumor/BBC’s live feed has it that many large companies are moving their execs out of Tokyo.

Stay or Go?

By the night of March 15th, four days after the earthquake, I was feeling the stress. We had already stopped giving tap water to our son, having him drink water we saved just after the earthquake. We wore cotton masks when we went outside, and kept the windows shut, even hanging our laundry indoors to dry. Among people in Tokyo, we were probably on the more cautious end of the spectrum, but not the extreme.

I was agonizing over the question of leaving Tokyo to get our son away from the radiation that a possible full-scale meltdown of one or more reactors at Fukushima might release. A colleague of mine had already taken her daughter back to Australia and urged us to get out, too. Family and friends overseas walked the fine line between begging us to leave and asking our intentions.(9)

Yet all around us, life had begun to return to something like normal. Trains were running again on most lines, blackouts were few (none in central Tokyo). People were on the street, going to and from work, shopping, playing in parks, most without even the face masks people routinely wear to keep out the springtime pollen. How could this be? It was like some kind of science fiction horror film in which normal people are oblivious and only the paranoid are reasonable. In part this was because of what people referred to as the “news gap.”

The News Gap

Many foreigners in Japan rely on English (or other language) media due to the difficulty of learning enough Japanese characters to read a newspaper easily, but also because the internet makes it possible to live transnationally, to maintain access to, and participation in, news and networks from our home countries and other countries as well.

For this reason we were probably the first to experience the news gap. When I took a break from searching for news online, my partner told me about a “breaking” story she had just seen on NHK’s live TV coverage. I had read the same news online hours before. This happened several times.(10)

My friend Yamasaki Seiichi, a fluent speaker of English and Japanese who was hired the day after the earthquake to take a team of journalists from Australia’s Channel 7 to Fukushima, had the same experience. As they drove toward Fukushima, “breaking news” came over the car radio about the status of the reactors. He interpreted for the Australian journalists who said, “Yes, we got that news (online) hours ago.”

It wasn’t just a question of timing, there was also a fact gap.(11)

The main Japanese media outlets mostly relayed the press releases and statements from the Tokyo Electrical Power Company (TEPCO) representatives and the Japanese government, sometimes providing commentary from pro-nuclear experts.

TEPCO engineers and government representatives held frequent press conferences in which they presented lots of data that, they said, pointed to the situation being stable and posing no immediate risk to human health.(12) Various figures presented in their frequent press conferences (reactor temperatures, water levels, pressure in containment vessels, etc.) assured the public that the situation was under control and posed no immediate danger.(13) The fuel was being cooled, the containment was intact.

News sources outside Japan described a more perilous situation with meltdowns likely already underway.(14) Of course the company and the Japanese government each wanted to spin the news — to preserve social order and to show their own efforts in the best light — but there was something else at work.(15) TEPCO and foreign observers seemed to be operating with different information — and they were.(16)

In the absence of hard information about the condition of the reactors — instrumentation had been destroyed in the earthquake and explosions and the reactors were too hot for workers to safely examine them — TEPCO and the government were basing their assurances almost entirely on calculations made on the basis of very optimistic assumptions about the state of the reactors.(17) But they were not the only ones making calculations. As William Broad explained in an April 2nd article in the New York Times (“From afar, a vivid picture of Japan crisis”) “Thanks to the unfamiliar but sophisticated art of atomic forensics, experts around the world have been able to document the situation vividly … the atomic simulations suggest that … three of the reactions at the Fukushia Daiichi complext [are] in some stage of meltdown.”

Freelance journalist Segawa Makiko lays out the role played by the mainstream media, in an article in Japan Focus:

“(A)t TEPCO press conferences… mainstream journalists simply record and report company statements reiterating that the situation is basically under control and there is nothing to worry about…There is one particularly telling example of the media shielding TEPCO by suppressing information. This concerns plutonium. [A]fter the reactor blew up on March 14, there was concern about the leakage of plutonium. However, astonishingly, until [nearly] two weeks later when [a freelance journalist] asked, not a single media representative had raised the question of plutonium at TEPCO’s press conferences.”(18)

On March 26, in response to [the journalist’s] query, TEPCO stated, “We do not measure the level of plutonium and do not even have a detector to scale it.” …the next day, Chief Cabinet Secretary Edano announced that “plutonium was detected.” When TEPCO finally released data on radioactive plutonium on March 28, it stated that plutonium -238, -239, and -240 were found in the ground, but insisted that it posed no human risk. Since TEPCO provided no clarification of the meaning of the plutonium radiation findings, the mainstream press merely reported the presence of the radiation without assessment… Nippon Television on March 29 headlined its interview with Tokyo University Prof. Nakagawa Keiichi, a radiation specialist, “Plutonium from the power plant — No effect on neighbors.”(19)

This crisis shines a spotlight on the passive corruption surrounding the atomic energy industry, the “nuclear power village.” “Nuclear industry officials, bureaucrats, politicians and scientists — all have prospered by rewarding one another with construction projects, lucrative positions, and political, financial and regulatory support.”(20)

The media play their part too. “As a major sponsor of several media outlets, Tepco buys the goodwill and, ultimately, the powerful silence of reporters, their editors, TV producers and publishers.”(21) Journalists with internet and foreign media were initially excluded from official press conferences after March 11, according to freelance journalist Takashi Uesugi, director of the newly founded Free Press Association of Japan.(22)

The news gap was invisible to people not following foreign or alternative media online until March 16th, when NRC chairman Gregory Jaczko urged the Obama administration to recommend the evacuation of all U.S. citizens within 50 miles (80km) of the Fukushima NPP. His testimony to Congress, reported in the mainstream media, flatly contradicted the government’s line.

The Japanese government had declared a mandatory evacuation zone of only 20km (first it was 2km, then 10km). People from 20 to 30km of the plant, said Prime Minister Naoto Kan, should stay indoors, and shut their windows. Japan’s Atomic Energy Agency still rated the accident a level 4 on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES), lower than Three Mile Island (5) and Chernobyl (rated a 7).(23) The fact that the U.S. government, still regarded as a voice of authority in Japanese politics, had publically contradicted the Japanese government was a blow to the TEPCO/Government media strategy of reassurance.(24)

That TEPCO and government regulators cannot be trusted to tell the truth is not really news. There have been repeated scandals at Fukushima and other nuclear power plants.(25) The Australian news team visiting Fukushima with my friend Yamasaki had him ask residents of a town near the reactors why they hadn’t fled. People gave various reasons, “this is my home, I have work here, I don’t have money to go anywhere, the government has not told us we need to evacuate.” When asked whether she believed what the government was telling them, one young mother said, “we don’t believe the government is telling the truth, but we have no choice but to believe them.”

It wasn’t that people were ignorant or gullible, but that knowing the truth in the face of decades of concerted propaganda takes effort — you have to seek out and assess alternative information, piecing reality together as best you can. When it comes to assessing the risks posed by a nuclear crisis, this is not an easy task.

For the people of Fukushima and neighboring prefectures, many living outside the evacuation zones but still exposed to radioactive “hotspots,” the news gap has been even more extreme. For them the question of risk is urgent, especially concerning children and pregnant mothers. Though they generally have less access to internet news sources (a digital divide), they have access to alternative news through grassroots organizations. In one town, members of the Japan Teachers Union (Nikkyoso, which has long opposed nuclear power) are organizing to evacuate children, remove contaminated soil from schoolyards, and take other measures.

I can’t adequately explain my decision. For my partner it was clear: her mother was in the hospital, she wasn’t going to leave her. That left it up to me. The university was between semesters and my son had only a week of school left before spring break.

I told myself my decision was based on my understanding of the risks, but the bottom line is like many others I simply didn’t know. where we stood. I knew TEPCO was lying, but not how much (most of the facts I report here were not confirmed until weeks or months after the crisis began). I didn’t know who was right about radiation risks, and I didn’t know where to draw the line. My decision to stay was in some way a commitment to share the fate of friends and neighbors, but I think it also reflects the paralysis of that mother in Fukushima. It takes a lot to tear free.

As it turns out my personal calculations about risk were largely meaningless. When I decided to stay, I didn’t know that three meltdowns had already happened, that the containments were breached, and it was purely a matter of chance that we and millions more had escaped a major exposure to radiation — the wind was blowing out to sea when the reactors exploded. As a friend who is a specialist in nuclear power who studied Chernobyl and Three Mile Island, told me, “once you know that the radiation is so dangerous you have to evacuate, it is too late.”

On the 15th and 16th the wind curled to the southwest, toward Tokyo. Having decided to stay, the next question was how to limit our exposure to radiation and how to be helpful; for the survivors and evacuees up north the situation was terrible.

Postscript: The question of stay or go has not gone away. In early June, Japan’s Nuclear Safety Agency revised its estimate of the amount of radiation released in the first week of the nuclear crisis, doubling it to nearly 800,000 terabecquerels. Three months later, there is still a possibility of a major explosion and release of radiation from the structurally unstable spent fuel pool in Daiichi reactor #4 and possible recriticality in Reactor #1.(26)

Notes

- One of the most distinctive features of this crisis, in my experience, has been the use of social media, particularly Facebook. For this article I consulted the Facebook updates and notes I and others posted over the last two months to provide a timeline and sense of the rise and fall of emotion. (I’m not the only one: 2:46 aftershocks, also known as #quakebook, is a collection of tweets on the earthquake and tsunami edited by a blogger in Japan. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/blog/2011/apr/14/quakebook-online-story-aid-japan)

back to text - The website of the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program is a great tool for learning about earthquakes and tracking recent activity. http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/recenteqsww/

back to text - More people were killed in the firebombing of Tokyo and other cities than in the atomic bomb attacks; according to an elderly neighbor, everything in our neighborhood, including eight of the nine Buddhist temples that surround us, was burned to the ground.

back to text - This animated infographic displays the proliferation of aftershocks: http://www.gfz-potsdam.de/portal/gfz/Neuestes/Aus+den+Abteilungen+-+Archive/Ressourcen/110316_Erdbebenanimation_gross?$javascript=disabled].

back to text - “23,482 confirmed dead or missing.” June 12, 2011 NHK World News http://www3.nhk.or.jp/daily/english/11_23.html.

back to text - Tokyo Occupational Safety and Health Center http://www.toshc.org (Japanese).

back to text - “Quake reconstruction may cost up to $184 billion, says Japan’s economic minister” International Business Times, May 22, 2011 http://www.ibtimes.com/articles/149946/20110522/japan-tsunami-recession-japan-s-economy.htm.

back to text - Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fukushima_Daiichi_nuclear_disaster.

back to text - Shiro Yabu’s account of her decision to leave Tokyo provides insight into the thinking of people who decided to leave: https://jfissures.wordpress.com/2011/05/18/leaving-tokyo/.

back to text - The news sources on which I relied changed over time. Initially the websites of NHK, the Kyodo News Service, Reuters, and the BBC were most useful. The New York Times was less timely, but had consistently good analytical coverage. U.S. Television news was generally not useful – too slow and too shallow. I discovered new sources like Russia Today and a very useful blog called Energy News (enenews.com) which collects the most relevant news for those concerned about the impact of the nuclear crisis. And I Googled “Fukushima,” first scanning the “Latest” then the “past 24 hours.”

back to text - In “Underground,” his oral history about the Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attack and the lives of victims and perpetrators, Murakami Haruki relates the fury victims felt towards the news media who they accused of exploiting them. I wonder if survivors of the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster will have the same feeling.

back to text - Engineers talk about “instrument blindness” that results when the instruments are the only source of information. TEPCO’s press conferences induced a kind of “data blindness” in which numbers were reported with no effort to analyze their meaning or implications.

back to text - My favorite example of spin was the announcement that “most of the fuel in the reactors did not melt,” which seemed to me to be like saying “most of your hair is not on fire.” Of course, it wssn’t even true.

back to text - See the remarkable timeline of official statements compiled by Reuters: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/15/us-japan-quake-timeline-idUSTRE72E2HQ20110315.

back to text - An article in the New York Times provides insight into the struggles between Prime Minister Naoto Kan and pro-nuclear officials. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/13/world/asia/13japan.html?ref=world.

back to text - An April 2nd New York Times article by William Broad titled “From afar, a vivid picture of Japan crisis” explains the difference. “For the clearest picture of what is happening at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, talk to scientists thousands of miles away…Thanks to the unfamiliar but sophisticated art of atomic forensics, experts around the world have been able to document the situation vividly….the atomic simulations suggest that …three of the reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi complex [are] in some stage of meltdown.”

back to text - James Acton, interviewed on the PBS News Hour http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/world/jan-june11/japan2_06-07.html).

back to text - The question of plutonium had already been raised and discussed in foreign media – it came up as soon as journalists discovered that Reactor 3 used MOX fuel, which was also stored in large quantities in the spent fuel pool of Reactor 4.

back to text - “Fukushima Residents Seek Answers Amid Mixed Signals From Media, TEPCO and Government. Report from the Radiation Exclusion Zone” (Updated May 16) http://japanfocus.org/-Makiko-Segawa/3516.

back to text - “Culture of Complicity Tied to Stricken Nuclear Plant,” Norimitsu Onishi and Ken Belson, The New York Times, April 26, 2011.

back to text - “The Japanese Press and TEPCO: from lapdog to pit bull.” Jake Adelstein. Number 1 Shimbun. http://no1.fccj.ne.jp/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=423:top-story-master&catid=65:front.

back to text - “Free Press Association of Japan takes on Cartel” Makiko Segawa, May 10, 2011, Shingetsu News Agency http://shingetsublog.jugem.jp/?eid=84.

back to text - It seems clear this wasn’t just a matter of the U.S. government being more conservative; the NRC was basing its policy on different models. Other governments, too, adopted much stricter evacuation standards for their citizens in Japan. (The U.S. govt offered evacuation. The U.S. embassy also made Iodine pills available to its citizens and their families. France, UK, Germany, and other countries went further, urging all citizens in Tokyo to evacuate as well.[wikipedia]) (http://en.rian.ru/world/20110315/163008635.html) http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2011/05/16/3217488.htm?section=world.

back to text - “(T)he public authorities have sought to avoid grim technical details that might trigger alarm or even panic. “They don’t want to go there,” said Robert Alvarez, a nuclear expert who, from 1993 to 1999, was a policy adviser to the secretary of energy. “The spin is all about reassurance.”” http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/03/science/03meltdown.html.

back to text - “Japan’s nuclear power operator has a checkered past,” Reuters, March 12, 2011.

back to text - “Exclusive Arnie Gundersen Interview: The Dangers of Fukushima Are Worse and Longer-lived Than We Think” ChrisMartenson.com June 3, 2011. http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2011/03/31/3177889.htm.

back to text

July/August 2011, ATC 153