Against the Current, No. 118, September/October 2005

-

On to September 24th!

— The Editors -

The NAACP's Future

— Malik Miah -

Muslims in Britain: After the London Bombs

— Liam Mac Uaid -

Solidarity with Iraqi Labor

— Traven Leyshon and Dianne Feeley -

The Message and Meaning of Groundings 2005: Walter Rodney Lives!

— Sara Abraham -

Creating A Movement for Reparations

— Andrea Ritchie -

Economic Crisis & Fundamentalism

— Susan Weissman interviews John Daly -

Kyrgyzstan After Akayev

— Susan Weissman - Attacks on the Academic Left

-

Assaulting pro-Palestinian Activism: Smear Tactics at U-M

— Nadine Naber -

Labor Studies Under Siege

— Stephanie Luce -

Racism & Conflict at Southern Illinois

— Robbie Lieberman - Celebrating the Revolutionary Centenary

-

Rehearsing for 1917: Russia's 1905 Revolution

— David Finkel -

A Hidden Story of the 1905 Russian Revolution: The Unemployed Soviet

— Nikolai Preobrazhenksii -

Rosa Luxemburg & the Mass Strike

— Lea Haro -

Lessons from the 1905 Revolution

— Hillel Ticktin - In Memoriam

-

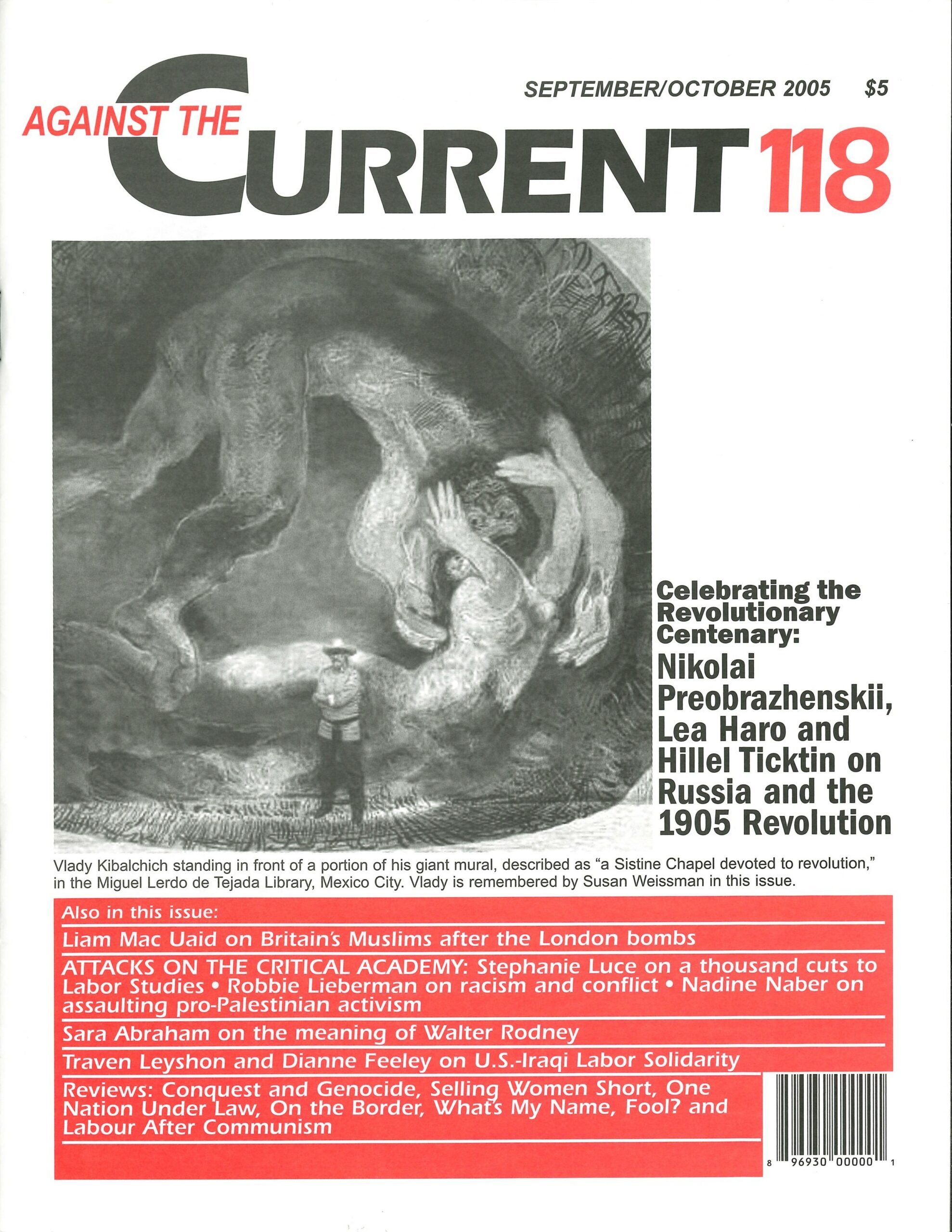

Remembering a Revolutionary Artiist: Vlady Presente!

— Suzi Weissman - Reviews

-

U.S. Law: Religious or Secular?

— Jennifer Jopp -

From the Front Lines of Native Women's Struggles

— Andrea Ritchie -

Fighting the Wal-Mart Plague

— Karen Miller -

Sports & Resistance

— Peter Ian Asen -

An Israeli Anti-Zionist Memoir: On the Border

— Larry Hochman -

Already in Hell: Labor After Communism

— George Windau

Lea Haro

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION of 1905 sparked strikes and protests all over Central Europe. In Germany the workers took an active interest in the Russian situation and demanded the presence of the SPD’s (Social Democratic Party) inspiring speaker, Rosa Luxemburg. For Luxemburg, the upsurge in strikes symbolized the revolutionary spirit of the working class. She became increasingly disillusioned and frustrated, however, with the SPD’s lack of support and the Trade Unions’ attempts to prevent strikes.

As revolutionary fervor faded in Germany and despite the persuasive efforts of her colleagues and friends, Luxemburg travelled to Poland in mid-December 1905 to participate in the Polish uprisings. Unfortunately, by the time she arrived the revolutionary struggle was already dying. Even though her participation in the Polish struggle was brief, it was enough to revitalize her enthusiasm and she embarked on the task of applying her Polish experience to the German situation.

Luxemburg was arrested March 4, 1906 by Polish authorities. A German conservative newspaper had exposed her presence in Warsaw. She was released from prison on July 8, 1906 and was finally allowed to leave Warsaw on August 8, 1906. She made her way to Finland, where the Russian revolutionary leaders had gathered. The Hamburg Provincial organization commissioned Rosa Luxemburg’s stay in Kuokkala, Finland to write the pamphlet that would become her classic statement: “The Mass Strike, the Party, and the Trade Unions.”

The Revolutions of 1905/06 marked a watershed in the practical and theoretical thought of Rosa Luxemburg. It was at this point that the changing nature of the SPD Executive, its shift to bureaucratic conservatism, became abundantly clear to her even while the true potential of mass strikes showed itself. The notion of mass strike was quite old; but the 1905 Russian Revolution was the first time that mass strikes were used to bring an empire to its knees.(1)

Luxemburg believed that the debilitating potential of spontaneous mass action could be utilized as a special weapon in times of revolutionary upheaval. Although Luxemburg intended mass strikes to be a tool used by the SPD in the overthrow of capitalism, her theory became threatening to all bureaucratic machines fighting for their own survival, first to the SPD and later to the Communist International. This article will discuss the reasons why the SPD and the Comintern feared Luxemburg’s concept of mass strike and the way in which both distorted her analysis to suit their own propagandist purposes.

The Tamed Opposition

First, Rosa Luxemburg’s newfound revolutionary enthusiasm posed a danger to the changing SPD and their relationship with the trade unions. By the time she returned to Germany, the revolutionary situation had returned to “normal” and she was shocked to find that the nature of the party had changed in her absence.

The party had become “official” and tame in its opposition. It behaved diplomatically and behind the scenes. Indeed, it behaved like a political party whose goal is to gain and maintain power within a parliamentary system, rather than a party whose aim is to overthrow the entire political and economic system. (Although the SPD had begun to change, it retained its Marxist rhetoric, which was not officially renounced until 1959.)

She was further shocked to discover the increasing influence of the trade unions. While she was away, the unions had regained their autonomy under a secret agreement, an incredible ceding of authority to the trade unions. The party Executive renounced any intentions of propagating the mass strike and pledged to take preventive measures. If a mass strike were to break out the party would bear sole responsibility for leadership and costs of the strike. Although trade unions would not participate, they promised not to betray the strike. Should lockouts and strikes occur after the mass strike was called off, then the union would step in and offer support.(2)

The increasing power of the trade unions made the party Executive reluctant of anything that might cause a confrontation with them. The party’s capitulation to the unions was so complete that the party executive put a last minute stop on the printing of Luxemburg’s “The Mass Strike, the Party, and Trade Unions.” The Executive had the original printing blocs destroyed and printed a mildly altered version of the pamphlet, having first removed any phrases that might antagonize the unions.

The Hamburg provincial organization was furious at the interference of the SPD executive. Not only had the most forceful strikes in 1905 taken place in Hamburg, but as Luxemburg’s benefactors they were keenly interested in her analysis of the Russian Revolution and its use of the mass strike.(3)

The trade unions, on the other hand, were mostly concerned with the practical consequences of using mass strikes for political purposes. Aside from the potential financial devastation that mass strikes posed, refocusing the workers’ attention on the revolutionary struggle, as opposed to the day-to-day struggle, threatened the Union leaders’ authoritative position. They feared that political discussions, and hope for radical political change, would lure the rank and file away from the practical work of the trade union struggle.(4)

Therefore, in an effort to draw the rank and file back to the trade union struggle and away from the abstractness of revolution, the SPD Executive and the trade unions distorted the meaning of her pamphlet. Luxemburg’s critics accused “The Mass Strike, the Party, and Trade Unions” of creating a false link between mass strike and revolution.

They felt she confused two separate issues — the economic and the political strike. They accused her of advocating a “theory of spontaneity,” a (mythical) theory which diminished the role of the party as the leader of the class struggle, overestimated the role of the masses, and denied the importance of conscious and organized action.(5)

The Executive and the trade unions’ invention of “Spontaneity Theory,” in fact, symbolized their own fears of losing control of the workers’ movement. Not surprisingly, their account of Luxemburg’s use of mass strikes was exaggerated and inaccurate; she did not advocate chaotic, leaderless, undisciplined or unconscious uprisings.

Luxemburg did not believe that the mass strike should be limited to a purely defensive measure, nor was it an isolated incident. In fact, the mass strike was “the sign” of the class struggle, which had developed over years. For Luxemburg, mass strike did not lead to revolution; but rather the revolutionary period created the economic and political conditions for mass strikes to occur. This spontaneous action by the masses could not be contained by discipline, planned, or tampered with by the party.

Luxemburg fully intended the party leadership to play an active role at the head of strikes. She did not believe that the leadership could plan the hour of the mass strike; the masses would have to decide for themselves the critical moment of the mass strike. She did, however, believe that the trend and character of the party would play a crucial role in determining the nature and the course the strikes took during the revolutionary period:

“To fix beforehand the cause and the moment from and in which the mass strikes in Germany will break out is not in the power of social democracy, because it is not in its power to bring about historical situations by resolutions at party congresses. But what it can and must do is to make clear the political tendencies, when they once appear, and to formulate as resolute and consistent tactics. Man cannot keep historical events in check while making recipes for them, but he can see in advance their apparent calculable consequences and arrange his mode of action appropriately.”(6)

The conditions for spontaneous action did not fall from the sky, nor did workers arbitrarily decide to “have” a mass strike. The economic and political conditions needed already existed. It was not only necessary for the party to play an active role in educating and preparing the proletariat for their historical role in the overthrow of capitalism; indeed the party was itself a pre-condition of a successful revolution.

Spontaneous mass action played a vital role during the revolutionary period. However, Luxemburg maintained that without the necessary pre-conditions even the most carefully planned and disciplined mass strike would be no different than an ordinary struggle for wages, and could potentially end in disaster. In order for a mass strike to be an effective revolutionary weapon against capitalism it was imperative that the desire and drive for mass action came from the masses — who had been guided and influenced by the party.

The party and the trade unions were not interested in Luxemburg’s true meaning. They were driven by fear of losing control over the rank and file. The workers’ excitement and enthusiasm for new weapons in the revolutionary struggle made Luxemburg’s analysis threatening to the hegemony of the SPD Executive and the trade unions. Their parliamentary pursuit of power contradicted their revolutionary rhetoric.

However, this would not be the last time that Rosa Luxemburg’s endorsement of revolution would pose a threat to an increasingly bureaucratized machine. As the Comintern became increasingly bureaucratic, Luxemburg’s concept of mass strike fell under scrutiny.

Comintern/KPD Factional Wars

Lenin’s death (1924) led to many changes in the Comintern, which like the SPD began to focus its attention on maintaining power rather than the procurement of revolution. This time the attacks on Luxemburg’s theories were factional ploys to divide and conquer the German Communist Party (KPD).(7)

In 1924 the KPD experienced its “Left turn” led by Ruth Fischer and Arkadij Maslow. Hostile to the old SPD theoretical traditions, they led an offensive against the remnants of Social Democracy and “Luxemburgism” in the Communist Party, during the spring and summer of 1925.(8) The main victim of this offensive was Rosa Luxemburg and her theories, even though the actual targets were the Right and Center wings of the party.(9)

The attacks were strategically played out. The Spartacists, who were former members of the SPD prior to the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, could not claim loyalty to Bolshevism during this period. (In fact, no one in Germany could do so honestly. The Bolshevik party only placed itself on the revolutionary map with its seizure of power in 1917.)

The Fischer-Maslow Left used the attacks on “Luxemburgism” to purge itself of the Right and Center and gain control over the party. The Comintern, on the other hand, supported the attacks as a method of ridding the KPD of those who opposed Soviet hegemony. At the Fifth Plenum of the Comintern held in April 1925, it declared that Luxemburg and her followers were “mistaken” for their “unbolshevik treatment of the question of ‘spontaneity’ and ‘consciousness,’ of ‘organization’ and ‘the masses,’” their incorrect appraisal of the role of the party; and their incorrect assessment of the role of the party.(10)

In this revival of the old “spontaneist” myth, Maslow, Fischer and the Comintern regurgitated the SPD’s 1906 arguments against Luxemburg’s Mass Strike. They continued to allege that she recklessly advocated the endangerment of workers’ lives through her promotion of “spontaneous mass action.” This was precisely the opposite of Luxemburg’s meaning. However, she was no longer alive to defend herself and times had changed.

In the old Comintern, during Lenin’s lifetime, various Communist parties retained autonomy and open debates were tolerated. Under the new post-Lenin Comintern, the parties were subject to the will and desires of the Soviet State. Any opposition had to be stamped out. Therefore, Luxemburg, as a critic of Lenin, and her supporters had to be purged.

Once the Right and the Center had been defeated the Comintern turned against the Left, leaving behind a severely weakened party. The Comintern’s intention was no longer to push the revolution forward, but rather, to contain and control the parties.

Rosa Luxemburg was “rehabilitated” in 1926 but by then the damage had been done and she no longer appeared threatening. A division had been set up to create a distinction between Rosa Luxemburg the person — Spartacist martyr and misguided thinker — and “Luxemburgism,” the mythical false “system” which was against “Leninism.”

Rosa Luxemburg the martyr was good, while her ideas and Luxemburgism were bad. Her alleged “crimes,” particularly her disagreements with Lenin, were considered “mistakes [which] towards the end of her life [she] began to understand and correct.”(11) The official Communist line claimed that if she had lived she would have seen the error of her ways.

The Comintern’s infantilization of Luxemburg’s capacity as a thinker had nothing to do with her theories, but rather served to undermine her followers. If the Comintern authorities could not destroy her influence then they had to manipulate the KPD’s members’ image of her. Her intellectual understanding of Marxism had been destroyed in order to discourage any future following of her theories.

Despite her apparently great contribution to German Communism she was re-invented as a semi-Menshevik, which in Comintern rhetoric was a heinous crime. Stalin claimed that she and Parvus developed the theory of permanent revolution, not Trotsky. “They [Parvus and Luxemburg] invented a Utopian and semi-Menshevist scheme of the permanent revolution (a monstrous distortion of the Marxian scheme of revolution).”(12)

The efforts of the Comintern were partially successful. Although her memory as a martyred leader lived on, her memory as a theorist was buried. The Stalinists finished what the SPD had started — they successfully distorted her desire to utilize the lessons learned from the 1905/06 revolutions.

Notes

- Paul Frölich, Luxemburg’s comrade and biographer, pointed out that the notion of “general strike” (aka mass strike) is quite old. It was mainly used as a weapon against the bourgeoisie for political purposes. However, in capitalist countries the idea of general strike as a weapon of the working class movement seemed to have gone out of fashion, particularly in Germany and Great Britain. It remained firmly placed on the shelf of academic discussion and strictly for defensive purposes, though Parvus (a maverick socialist thinker who also collaborated with Trotsky in formulating the theory of Permanent Revolution) advanced the idea that it could move the masses from the defensive to the offensive struggle. Most SPD leaders were of the opinion that “General strike is general nonsense.” Paul Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work, 1940 (New York: Howard Fertig, Inc., 1969), 150-151.

back to text - The contents of the secret agreement were eventually leaked. It betrayed the 1905 Jena Congress resolution in which the party supported and indeed advocated mass strike under certain conditions. Carl Schorske, German Social Democracy 1905-1917: The Development of the Great Schism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1956), 48-49.

back to text - JP Nettl, Rosa Luxemburg, 2 vols. (London: Oxford University Press, 1966) 1:357, 365; Schorske 54-55.

back to text - Schorske 39-40; Nettl 1: 299-300.

back to text - For a Marxist defense of Luxemburg’s “Spontaneity Theory” refer to Frölich, 166.

back to text - Rosa Luxemburg, “Mass Strike, the Party, and Trade Unions,” Rosa Luxemburg Speaks, ed. Mary Alice Waters (New York: Pathfinder Press, Inc. 1970) 205.

back to text - This discussion will inevitably be somewhat confusing to readers without some knowledge of SPD and early Communist history. In 1914, the party Executive’s support for war credits in 1914 split the SPD into three, but the official break came in 1917 when the Left and Center were expelled from the party. The center (led by Karl Kautsky) formed the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), and the Left formed the Spartacus League, which became the German Communist Party in 1919 (KPD). Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, the leaders of the Left, were murdered in 1919 by a military death squad authorized by the Rightwing SPD government.

back to text - Ruth Fischer blamed Russian interference in the division of the KPD. She insisted that Manuilsky was sent to Germany to manipulate and prevent the party from forming a united opposition to Moscow. She claimed that he manipulated KPD politics with promises of Soviet support pitting the right and against left in an effort to gain supremacy over the KPD. Fischer asserted, “If the party could no longer be manipulated, then its integration into a stronger form could only be opposed by the manipulator. His job was clear: by some means to prevent the integration of the three principal factions of the German party into one working unit.” However, Fischer’s defense neglected her own participation in the attacks against the right. The Left were sufficiently lured by promises of power and when they were no longer of use they were discarded. Ruth Fischer, Stalin and German Communism: A Study of the Origins of the State Party, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1948), 441-443.

back to text - The KPD Right and Center wings consisted mainly of the old Spartacists. They remained loyal to Luxemburg’s theories and, consequently, were skeptical about Soviet domination of the KPD and the Comintern. In her attacks Fischer made no differentiation between Right and Center. Ruth Fischer, “Meeting of the Enlarged Executive,” International Press Correspondence 5.31 (1925), 407.

back to text - Lenin and Luxemburg had disagreed on many issues, including party organization. For example, Luxemburg in 1903-04 criticized Lenin’s propagation of a highly centralized party structure. For these debates on party organization please refer to Lenin’s What is to be Done? (1902), Luxemburg’s reply Organizational Questions of Russian Social Democracy (1904), and Lenin’s reply One Step Forward Two Steps Back (1904). Although Luxemburg was “rehabilitated” in 1926, her position on party organization was continually attacked in Comintern literature, and KPD training material described Luxemburg’s “erroneous” view on party organization. Kursusmaterial über Organisationsfragen der KPD — Mai 1929 3-4. SAMPO FBS 248/11598, RY 1/I2 /707/99; For further details of the theses adopted at the Fifth plenum see “The Theses on the Bolshevization of Communist Parties Adopted at the Fifth ECCI Plenum,” ed. Jane Degras, 3 vols. (London: Frank Cass and Company Ltd, 1971) 2: 191.

back to text - A. Martinov, “Lenin, Luxemburg, Liebknecht.” The Communist International 10.3-4 (1933), 141; “Luxemburg to Lenin or Luxemburg to Kautsky?” The Communist International 6.7 (1929), 214.

back to text - Joseph Stalin, “Some Questions Regarding the History of Bolshevism,” The Communist International 8.20 (1931), 666. For a further description of Luxemburg’s “semi-Menshevik” mistakes see Martinov, “Lenin, Luxemburg, Liebknecht,” The Communist International 10.3-4 (1933) 140, 141-142.

back to text

ATC 118, September-October 2005