Against the Current, No. 108, January/February 2004

-

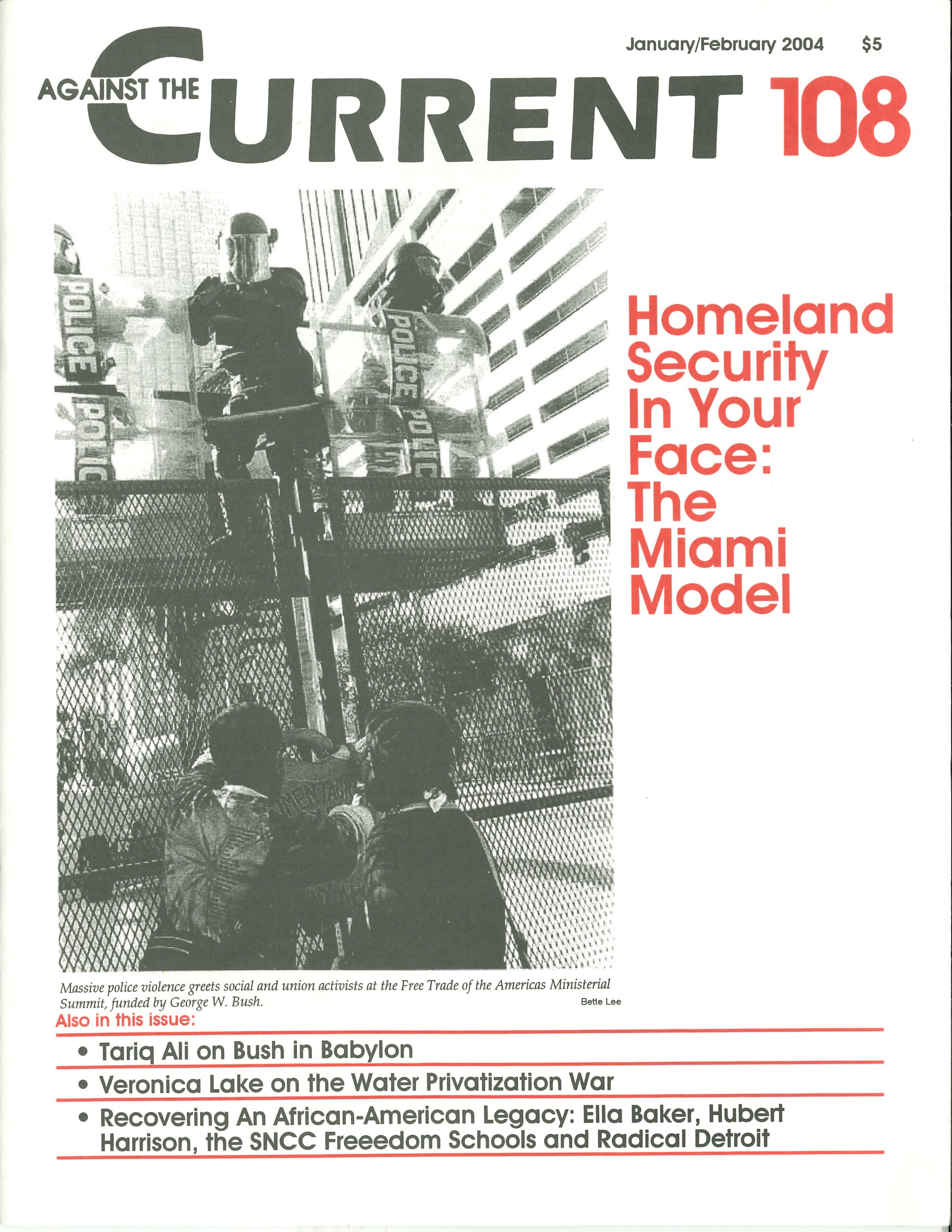

The Miami Model in Your Face

— The Editors -

Black Voters in 2004

— Malik Miah -

Looking at Bush in Babylon

— interview with Tariq Ali -

Eyewitness Chile: After 30 Years

— James Cockcroft -

Iran on the Verge of Revolution?

— Hassan Varash & Hamid Naderi -

Privatizing Water, The New World War

— Veronica Lake -

Matt Gonzalez & San Francisco's Green Earthquake

— Rich Lesnik -

What's Behind the Economic Upturn?

— Loren Goldner -

Amer Jubran: From Exile to Exile

— David Finkel -

On the History of Human Nature

— Jim Morgan -

Random Shots: What Do You Worship?

— R.F. Kampfer - Labor's Battles

-

Unions Confront A Restructured Industry

— Joel Jordan -

University of Minnesota: Dignity vs. Cutbacks

— Corey Mattison -

How Strikers Educated Miami University

— Dan La Botz -

The UAW Contract's Downhill Spiral

— Ron Lare & Judy Wraight - African-American History in Retrospective

-

Sampling New Black Radical Scholarship

— Alan Wald -

The Freedom Schools, An Informal History

— Staughton Lynd -

Whose Detroit? A City's Upheaval

— Nicola Pizzolato -

The Vital Legacy of Hubert Harrison

— Allen Ruff - Reviews

-

Eva Kollisch's Girl in Movement

— Lillian Pollak - In Memoriam

-

Sam Phillips & Sun Records

— George Fish -

Jack Barisonzi, 1933-2003

— Patrick M. Quinn

Joel Jordan

“A strike of one day, one month or even one year will not cause the offer to improve” –Larree Renda, Safeway Vice President, in a video shown to Von’s (Safeway) workers in early October 2003.

“We want to throw this question out there, How do we win this strike? Because we can’t lose it.” –Greg Denier, United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Communications Director, December 2003.

AS THE STRIKE/LOCKOUT of 70,000 grocery and food workers throughout Southern and Central California stretches into its third month, union workers in and out of the food industry understand how pivotal it is.

Southern California is the largest retail food market in the United States, accounting for about 20% of the total sales of the three supermarket chains at the center of the dispute — Ralph’s (owned by Kroger), Albertson’s, and Von’s (owned by Safeway).

These chains, next to Wal-Mart, are second, third, and fourth in grocery sales nationally. What happens in Southern California will set a pattern for all subsequent supermarket contracts as well as a establish a tone for all union-management negotiations regardless of industry.

From the beginning, the strike has enjoyed surprising support among customers. Ironically, efforts by the chains to encourage closer, more personalized employee-customer relations backfired as food shoppers, regardless of ideological persuasion, have refused to cross picket lines staffed by people they know and like.

As a result, it is estimated that the three chains have already lost some $500 million in sales through November as shoppers are flooding local union-organized chains that have signed “me-too” agreements or various union and non-union independent markets and club stores.

The labor movement in Southern California has revved up support for this strike as never before. Throughout the strike, the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor has organized support rallies and encouraged AFL-CIO affiliated unions to join UFCW picket lines at the stores.

It has sent out mailers signed by supermarket clerks encouraging a boycott of Von’s and Albertson’s stores because “We can’t protect our health insurance unless we have your support.” In November, the International Warehouse and Longshore Workers Union (ILWU) shut down the Los Angeles harbor for one day and held a demonstration of 5,000 strong. The national AFL-CIO has promised to solicit contributions to the UFCW strike fund.

Employers’ Solidarity

While the three leading supermarket chains in the area have formed a united management team, the seven UFCW locals have pursued a divide and conquer strategy, especially targeting Safeway while attempting to split off Ralph’s (Kroger) from the other two chains.

First, UFCW struck Von’s on October 11, but Albertson’s and Ralph’s immediately responded by locking out their store employees. Then, on October 31, the UFCW decided to pull the pickets at Ralph’s stores and encourage people to shop there, as a “reward,” according to Rick Icaza, President of Los Angeles UFCW Local 770, for “consumers who have respected our picket lines.”

In response, the chains publicly declared their solidarity as well as their agreement to share profits and losses during the dispute. After pulling the Ralph’s pickets, the UFCW set up informational picketing at Safeway stores in the California Bay Area, Washington D.C., and other metropolitan areas urging Safeway customers to shop at other unionized stores.

On November 24, the strike received a much needed boost when UFCW picket lines were extended to the ten warehouses (distribution centers) of all three chains, as local International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) officials announced that 7,000 warehouse workers and drivers (whose contract expires in two years) would honor the picket lines and refuse to work.

Before this, Teamster drivers were driving up to the picket lines at the stores and allowing store managers with recently received Class 1 licenses and professional scabs to drive the delivery trucks through the lines.

The Issues

The strike, by far the largest and most important local strike in many years, came about when UFCW members voted overwhelmingly (97%) to reject a proposed concessionary contract. The main issue is health care benefits: Citing rising cost, the employers are demanding a cap on health-care coverage.

Supermarket workers now enjoy fully funded health care, the most attractive feature of the job considering that most earn less than $12 an hour and are guaranteed no more than twenty-four hours work a week. The cap would mean that workers would have to pay as much as 50% of the cost of medical care — which given their income would be prohibitively expensive.

Related to this are the employers’ demands for a two-tiered wage and benefits system, as well as for various work rule changes giving them “flexibility” and the right to open up non-union stores.

The chains claim that they need cost relief from the union if they are to compete with non-union Wal-Mart, by far the largest food retailer in the United States, which is set to build 40 Supercenters in California over the next five years.

UFCW counters that the threat from Wal-Mart is exaggerated and that the big three supermarkets are merely attempting to pad their already hefty profit margins. But the real explanation for the hard line taken by the employers would seem to lie in three related developments.

First, in the past thirty years and especially in the last decade, the supermarket industry has been transformed from thousands of primarily local and regional chains into four or five gigantic national corporations dominating the market.

Second, in recent years the supermarket chains are increasingly facing intense competition from non-union companies, especially Wal-Mart.

Third, the UFCW and the Teamsters have failed to organize themselves nationally to combat the growing concentration of power within the industry. Until the unions confront this weakness, they will continue to take big hits from the big three chains, Southern California being no exception.

Let’s look at each of these developments.

Consolidation and Competition

Historically, Southern California was characterized by several intensely competitive local and regional supermarket chains. But when the smoke cleared after the national wave of mergers in the middle and late `90s, the big three chains emerged dominant locally and nationally.

In Southern California, Safeway gobbled up Von’s; Albertson’s bought Lucky’s; and Kroger absorbed Hughes and Ralph’s, which had earlier bought out Alpha Beta and Boy’s Market. As the current strike/lockout began, the big three accounted for almost 60% of grocery sales in Los Angeles County and 66% in San Diego County. Nationally, the big three now account for over half of all grocery sales.

In the 20-year period between 1977-1997, the percentage of total sales of supermarket firms with 1000 or more employees rose from 55% to 65%. Through consolidation, companies are aiming to strengthen their buying and marketing power to fend off competition from Wal-Mart.

In an industry that grows less than three percent a year, the big three (plus Ahold, the fifth largest chain) are locked in a pitched battle especially with Wal-Mart, but also with the club stores and dollar stores, for “market share.”

So far, they are losing, as their share of total retail food sales has fallen from 54% in 2000 to 50% in 2002. On the other hand, Wal-Mart’s share during the same period rose from 9% to 14% with the club and dollar stores rising 1% each.

Such competition, combined with economic recession, has spelled bad times for the big three. Profits have slumped badly in 2003. More importantly, “identical store sales,” an industry barometer measuring sales at stores open for at least a year, have either stagnated or dropped over the past two years.

To compete, the supermarkets have been compelled to reduce prices, which, in turn depresses profits, which in turn necessitates cost cutting, which, in the final analysis, compels them to attack the wages and benefits of their workers.

Industry analysts estimate that the major grocers, which are 75-80% union organized, pay 20-30% more in wages and benefits than does non-union Wal-Mart, a gap made ever more expensive by the exponential rise in the cost of health care benefits. Not surprisingly, Wall Street investment houses are firmly lined up behind the big three’s stand against the unions to cut operating costs.

Unions in a Changing Industry

This analysis suggests that it is a mistake to attribute the behavior of the chains to “corporate greed,” as does the UFCW and the left for the most part. In fact, to take this position actually weakens the strike precisely because it minimizes how important it is economically for the employers to get these concessions.

If, as the UFCW suggests, the employers are swimming in profits, one would think it wouldn’t take too much of a fight to get them to see how costly the strike is for them and negotiate a decent contract.

But if the employers are driven to extract concessions from their workers to defend their position in the industry, then the unions need to find a way to make the strike so costly for the chains that they will be willing to back off their demands on the unions even if it further jeopardizes their position in the industry.

The “corporate greed” line plays to the populist sentiment that corporate attacks on workers are primarily psychological, rather than necessitated by the logic of the capitalist system, in particular, business competition. But it doesn’t square with reality.

The Southern California grocery strike, more than anything, points up the historic failure of the food worker unions, UFCW and Teamsters alike, to respond to the dramatic changes in the food industry over the past few decades.

Food industry contracts are still negotiated separately by local or region as well as by union, even though the chains involved are, and have been for some time, national.

At one time, locally negotiated contracts made sense because the companies involved were local. Strike them and you hit their whole operation. But as the four national supermarket chains emerged, the UFCW and the Teamsters failed to organize together for a national contract from the big grocers.

The unions were left vulnerable to getting picked apart, local by local, by the powerful chains who are on the offensive all over the country.

In the recently concluded West Virginia, Ohio and Kentucky strike against Kroger, UFCW members accepted a contract that puts a cap on the employer’s annual contribution to the union’s health care plan — exactly what the big three want the Southern California unions to accept.

Teamsters could not have won the UPS strike in 1997 if it had struck the company on a piecemeal, local-by-local basis. Yet that is how the UFCW and the Teamsters are attempting to take on these three behemoths of the food industry. This more than anything else puts the union at a great disadvantage, even in the huge Southern California grocery market.

Strategic Weakness

This position of weakness has left the UFCW in Southern California with limited options, short of a major change in union strategy.

The UFCW line of attack has been to split the employers, though from the beginning it appears to be based on wishful thinking. When the UFCW decided to selectively strike Von’s (Safeway) and not Ralph’s (Kroger) or Albertson’s, the latter two retaliated by locking out their UFCW employees.

The UFCW decided to close down the picket lines at Ralph’s even though the big three had an agreement to share all profits and losses in the strike. So now, the chains have even less of an economic incentive to compromise with the union.

That the employers will hang together throughout this strike is also borne out by the economics of the industry. While Kroger is in relatively better financial shape than the other two, all three face the same structural problems discussed above.

They have made it clear that they are prepared to wait out the strike no matter how long it takes. And with more than $30 billion apiece in annual sales, they have the resources to do it.

One could argue that removing pickets from Ralph’s freed up people to set up informational picketing around the country to gain support and build a Safeway boycott. Without pulling out the UFCW members in those areas, however, such picketing has limited effectiveness. Unless customers see their “own” workers walk out of the stores, they will generally continue to shop there.

To match the power of the chains, clearly a national sympathy strike is needed. If the UFCW had its act together, it would urge all its members working for Safeway, Kroger and Albertson’s to honor and join UFCW picket lines, thereby dramatically escalating the economic pressure on these firms.

Safeway, for instance, with 33% market share in the Bay Area, is the 500-pound gorilla. The UFCW contract there expires in September, 2004. A concerted effort to shut down Safeway there as well as in Southern California would be a step in the right direction.

Lack of Unity

Unfortunately, since its inception in 1979 the UFCW has generally agreed to concessionary contracts rather than promote solidarity among bargaining units or unions. Beginning with the 1981 recession, the union throughout the country agreed to two-tiered wage systems and the conversion of full-time to part-time jobs.

By 1990, only 38% of employees at the average chain market store were full time, most of whom start at near minimum wage. In Southern California, the UFCW had gone along with the national trend toward part-timers.

This disunity between local unions has been well illustrated in the current strike. The UFCW and Teamsters working for the same companies negotiate their contracts separately and at different times.

Southern California Teamster drivers and warehouse workers, whose contract expires in two years, are directly affected by the contract the UFCW workers get. Yet Teamster officials have offered contradictory support to the UFCW during the strike.

When the strike began, most Teamster warehouse workers and drivers continued working. They did honor UFCW picket lines at the two distribution centers where the UFCW had members; yet they discouraged active Teamster support, telling them that it was illegal to picket with the UFCW.

In one instance, Teamster officials called the police on one teamster warehouse worker who was determined to picket with the UFCW at one of those distribution centers. When the police told them it was legal, they got the UFCW to ask the teamster not to walk the line or risk non-support from the Teamsters. He reluctantly agreed.

Nevertheless, about a week later, in a show of “good faith,” Teamster officials got the UFCW to withdraw its pickets from those distribution centers so the Teamsters could go back to work.

Meanwhile, Teamster officials kept promising to pull out all 7,000 Von’s, Ralph’s and Albertson’s drivers and warehouse workers from all ten distribution centers. After stalling for three weeks, under pressure from UFCW, they finally pulled them out just before Thanksgiving, a time when most people had already done their holiday shopping.

Worse, after pulling their members out, Teamster officials ordered their members to go home, rather the encouraging them to picket with the UFCW. They continued (and still continue) to tell their members that picketing with the UFCW is illegal, even though it is protected free speech activity that any labor lawyer will tell you is perfectly legal.

Finally, two weeks after Teamsters began honoring the picket lines, International Teamster President Hoffa finally agreed to grant Teamsters $200 a week out-of-work benefits.

This kind of <169>support<170> is why rank-and-file teamster activists worry that their officials may soon try to get their members back to work even while the strike continues.

The Rank and File

Unfortunately, the UFCW as well as the Teamsters rank and file are not well enough organized to pressure their officials, much less offer themselves as an alternative leadership. Most of the strikers are young, with no previous union experience. Around 70% work part-time.

No rank-and-file network exists within the big Los Angeles Local 770, even though picketers constantly complain about the lack of information and direction provided by the union leadership. While Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) has some members in the food industry, their influence is still small.

Some strike supporters have made efforts to work with UFCW (and Teamster) rank and filers to initiate network building around the idea of putting the pickets back at Ralph’s and expanding the strike beyond Southern California. Yet once the Teamsters went out, the more militant UFCW members were hesitant to start organizing independently in the hopes that the Teamster support would win the strike.

Meanwhile, some TDU activists are defying the union leadership and have organized rank-and-file teamsters to at least be present at the distribution centers, if not actually walk with the UFCW pickets. Out of these kinds of efforts, TDU members may be able to expand their influence in the Southern California food industry.

But the length of the strike is taking its toll on picketers. The $200-300 per week strike benefits provide for emergencies, but in the long run do not pay the rent or put food on the table. Barring an about-face in union strategy, the ranks are being set up to accept another concessionary contract.

Difficult Prospects

We are witnessing another instance of the classic “race to the bottom” with inadequate resistance.

The supermarket chains are unified in their response to the threat of non-union Wal-Mart in a highly competitive, slow-growth, increasingly non-union industry. Even though the UFCW and the Teamsters are national unions, they have not kept up with the consolidation of the industry, putting them in the unenviable position of taking on gigantic corporations on a local-by-local basis.

The inexperienced rank and file are not yet ready to organize themselves, much less challenge the leadership with new ideas and strategies.

Since it is unlikely that the official union leadership will do so, one can hope, though, that out of this experience the ranks will begin to see the need to organize around developing:

* A national strategy to fight the corporate offensive in the food industry, including militant mass picketing involving the labor movement and its allies to stop production by stopping the scabs.

* A national campaign to organize non-union Wal-Mart and other non-union retailers to prevent the race to the bottom.

* Support for a single-payer health care plan that would put the issue of the right to health care in the public arena, where it belongs, rather than tying health care to competitive pressures on employers.

* Rank-and-file communication between UFCW and Teamster members to overcome the disunity.

ATC 108, January-February 2004