Against the Current, No. 108, January/February 2004

-

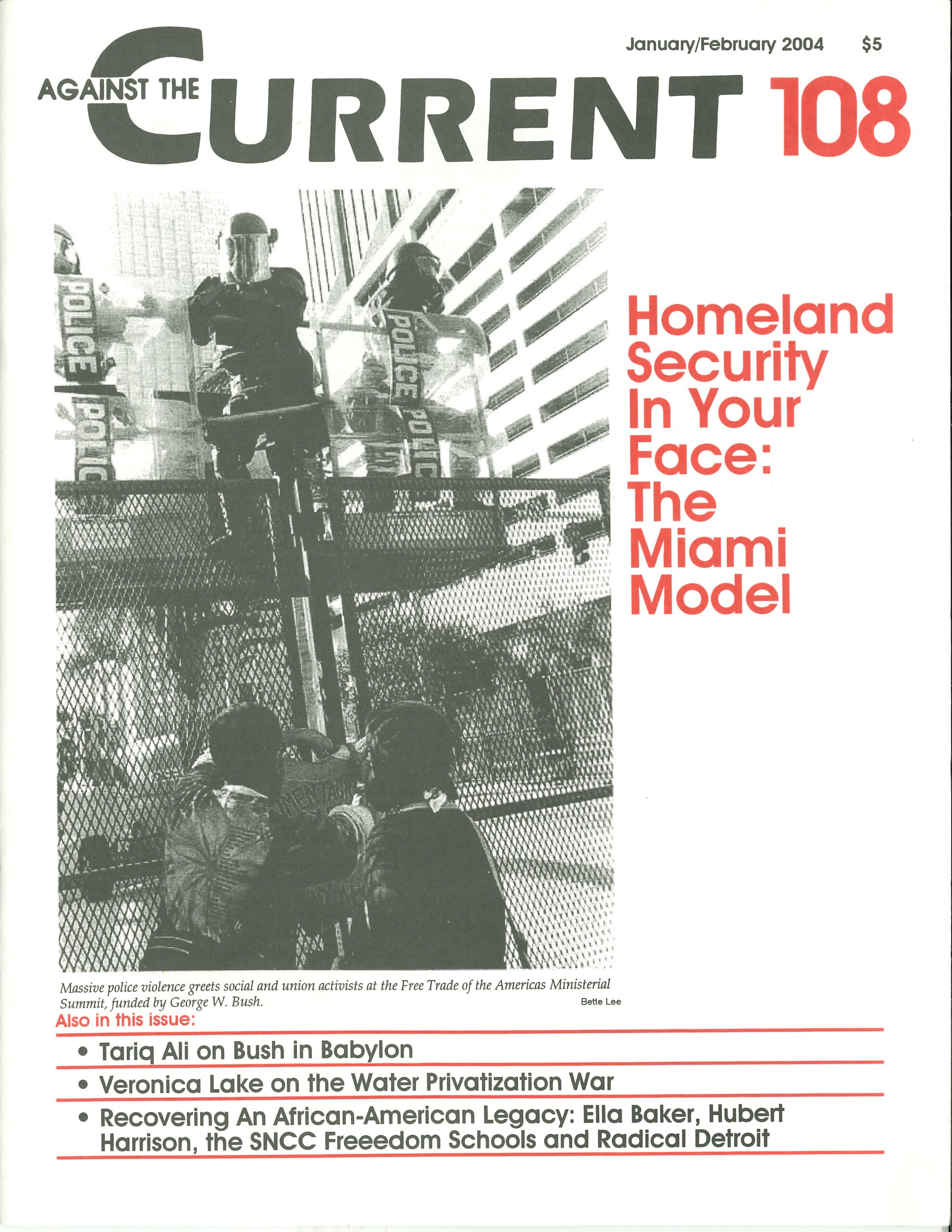

The Miami Model in Your Face

— The Editors -

Black Voters in 2004

— Malik Miah -

Looking at Bush in Babylon

— interview with Tariq Ali -

Eyewitness Chile: After 30 Years

— James Cockcroft -

Iran on the Verge of Revolution?

— Hassan Varash & Hamid Naderi -

Privatizing Water, The New World War

— Veronica Lake -

Matt Gonzalez & San Francisco's Green Earthquake

— Rich Lesnik -

What's Behind the Economic Upturn?

— Loren Goldner -

Amer Jubran: From Exile to Exile

— David Finkel -

On the History of Human Nature

— Jim Morgan -

Random Shots: What Do You Worship?

— R.F. Kampfer - Labor's Battles

-

Unions Confront A Restructured Industry

— Joel Jordan -

University of Minnesota: Dignity vs. Cutbacks

— Corey Mattison -

How Strikers Educated Miami University

— Dan La Botz -

The UAW Contract's Downhill Spiral

— Ron Lare & Judy Wraight - African-American History in Retrospective

-

Sampling New Black Radical Scholarship

— Alan Wald -

The Freedom Schools, An Informal History

— Staughton Lynd -

Whose Detroit? A City's Upheaval

— Nicola Pizzolato -

The Vital Legacy of Hubert Harrison

— Allen Ruff - Reviews

-

Eva Kollisch's Girl in Movement

— Lillian Pollak - In Memoriam

-

Sam Phillips & Sun Records

— George Fish -

Jack Barisonzi, 1933-2003

— Patrick M. Quinn

Veronica Lake

“Water is a critical and necessary ingredient to the daily life of every human being, and it is an equally powerful ingredient for profitable manufacturing companies.” –Mike Stark, senior executive at US Filter, a Vivendi subsidiary

“The aim of modern science is to reach an understanding of the world, not merely for purely aesthetic reasons, but that it may be ordered to our purpose.” –Gerard J. Milburn, theoretical physicist

“The fundamental difference here is between the concept of water as a commodity to be gobbled up (western water rights) vs. the concept of water as a part of all life for all of us so that its value in place and providing for the range of uses should be paramount (riparian). To divorce water from its critical role in our ecosystem, and to place value only on those human uses that have a price, which is what western rights have done, is about the same as the argument that a human being is worth only a few bucks when you take our different elements and chemicals and sort them out. The same amount of water outside a human being is worth very little compared to the value of the water as a part of a human being — to talk as if the value of the water to the irrigation project is greater than that to the living ecosystem from which it comes is wrong.” –Ann Woiwode, Director Sierra Club Mackinac Chapter

CAPITALISM AND CORPORATE science have colluded to bring us the latest, most insidious crisis. According to the United Nations research, 1.3 billion people in the world today lack access to clean water and 2.5 billion do not have adequate sewage and sanitation. The human suffering and environmental damage that those figures represent is unspeakable.

Cholera, fish die-off and desertification are only a few direct results of this perverted perception of “resource management.” At the same time, worldwide demand for water is doubling every twenty years, twice the rate of the population growth. By the year 2025, demand for fresh water is expected to outstrip global supply by 56%. Many major rivers in the United States have been allocated by local law to give 150% of their waters to human pursuits, as is the case in California.

There are a surprisingly small number of corporations taking advantage of this newly created water market. Suez, Vivendi and RWE/Thames are three of the main companies who have, with their subsidiaries, entered the market for the exploitation of water management.

Vivendi and Suez control approximately 70% of the existing world water service market. Other companies have taken on the “mining” or extraction of water for profit, Nestle and its subsidiary Ice Mountain being one that is currently depleting aquifers across the United States.

Maude Barlow, of the Council of Canadians and noted author of Blue Gold, has stated that as the wars in the past were fought for oil, the wars of the future will be fought for water. These water wars play out in communities in a variety of forms.

Corporations are taking control of the world’s water in three ways: (1) through “water mining” of the aquifers and vast sources of water that feed streams, and rivers; (2) through long-term leases or concessions allowing corporations to take over the delivery of water systems and the collection of revenues; (3) through “managing” municipal water systems.

Water is turned into a commodity to be exploited, not a public trust resource and most certainly not an intrinsic part of an integrated ecosystem that exists for its own reasons and not for “use.” What does this leave for non-human communities in the war for water? Essentially, less than nothing, and that is most emphatically the point of this push to create a market for the basis of all life.

In fact, this perspective demands running the world as a corporation at a profit, with pressures as powerful and far-reaching as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Since neither poor human communities nor local flora and fauna can pay for their water usage, they are denied access. In the language of profit and property, they don’t matter.

The Example of South Africa

As Patrick Bond, author and South African anti-privatization activist, said at a recent talk in Detroit, “There are a growing number of poor people who are inconvenient to the needs of the government and business; they don’t provide profit or service. They are a social liability and the government wishes they would just die off.”

Despite the African National Congress promise to the people in the South African constitution, which states that all essential services (shelter, water, heat and electricity) are guaranteed to each citizen, the austerity measures that the World Bank imposes are more compelling than a national mandate from the population that waged a revolution to accomplish this guarantee. These austerity measures mandate the privatization of essential services, no matter what the cost to the land or the people.

Because the poor in South Africa are being denied access to clean water for non-payment and must walk many miles to contaminated (but free) water wells and springs, cholera rates currently exceed what they were under apartheid.

Yet there is no actual shortage of water in South Africa. In the more affluent neighborhoods, pools are filled and lawns are watered. It is more cost effective for the managing corporation to provide decadently high volumes of water to the affluent, than to provide even meager amounts to poor neighborhoods lacking modernized infrastructure like plumbing and delivery systems.

The divide between the haves and the have-nots has become an increasingly familiar story in so-called Third World, or lesser developed nations. On the part of radical movements in the more developed/ industrialized countries, there is concern over the situation — evidenced by the large, international demonstrations against the World Bank, IMF and World Trade Organization wherever they rear their unnatural heads to meet.

Yet there is also a comfortable sense on the part of many of these anti-globalization activists of being unimplicated, unconnected to the crisis. Quite the contrary: The inflated water usage of “modern” society — and the industrial use and contamination that support it — jeopardize the whole world’s water supply and are evidenced in world-wide water level drops.

The geographic distance between the Third World and the developed world is illusory — we are always connected by water. Bodies of water define the features of the Earth and connect them; the water that flows through the hydrologic cycle brings the Earth and atmosphere together; the water that flows through our bodies joins us to each other and to the planet.

For corporations, water represents only new markets to be plundered. The concepts of nations and cultures, of bioregions and ecosystems are meaningless.

“(B)ut one of the great losses we endure in this prison of our own making is the collapse of intimacy with others, the rending of community, like tearing a piece of paper until there remains only the tiniest scrap.” –Derrick Jensen, A Language Older Than Words

Detroit and Highland Park, Michigan

As privatization capitalizes on the “underdevelopment” of the municipal water systems and bodies of water located in many of the cities and rural places in Europe and the United States, what were considered to be Third World conditions are increasingly becoming part of the developed world’s reality.

A few blocks from where this article is being written, people are fighting for their lives, for their homes and for the integrity of their families. Last year, several seniors died in their homes in Detroit in the cold and dark, victims of a new policy for water and gas allocation.

The new policy came into effect when Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick, lobbied by privatization companies, hired Victor Mercado to redirect Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department. Victor Mercado formerly directed Puerto Rico’s water department — directly into the hands of United Waters (a subsidiary of Suez).

Water shutoffs, poor water quality and non-repair of infrastructure were hallmarks of Mercado’s time in Puerto Rico. As one of the highest paid administrators in Detroit, Mercado brings his own special blend of multicultural make-believe and corporate pimping to the city.

Mercado was welcomed to the city as the highest ranking Hispanic American by Detroit’s sizable Mexican-American population, which is in large part working poor or working class on Detroit’s southwest side. But it has been corporate, not community, interests that Mercado has pursued.

Within a week of Mercado’s arrival, hundreds of city worker jobs were unfunded, some workers were fired, merit evaluations developed for remaining workers and thousands of Detroit residents threatened with the shut off of service.

Last year alone, over 40,000 addresses in the city proper lost their service for non-payment. This year, thousands more are being cut off before November, to sidestep a promise made last year to keep utilities on between November and March. It should be understood that Detroit has many older residences that use steam heat so a loss of water access means a loss of heat.

The city-wide crisis is monumental. Some $7.5 million are involved in outstanding residential accounts. Thousands of jobs have been lost in the city, due to the NAFTA-inspired relocation of manufacturing concerns. Former federal assistance programs to help unemployed and indigents with utility bills have been unfunded, all those social service funds being redirected to the military budget.

It is important to note that the city also had 300 corporate accounts that were outstanding, in the amount of millions of dollars. None of these corporate accounts have been closed on as a result of non-payment — although if even a small percent of what was owed by these industries were paid, the Water And Sewerage Department would recapture the money to cover the residential accounts owed.

Detroit was primed for privatization in what appears to be a world-wide pattern of privatization. According to Sanjay Sharma (Water Workers Alliance, Delhi, India), the formula goes something like this: defame, de-fund, deregulate and privatize.

Stories defaming the water department were circulated in Detroit’s local media. Statements claim the water department is antiquated. Corruption was in part the cause, but doubt was even cast on its water quality. This raised concerns in some 273 surrounding communities supplied by Detroit municipal water, which sued the city and demanded an investigation.

Mercado, claiming to be responding to these charges, implemented austerity measures of firings, non-repairs, and cutoffs of service. This in turn, put the city into the second stage of privatization, de-funding. During de-funding, the prior claims of poor service and disaster come true as the funds to provide good service disappear.

Now, we are in the last stages, where the purveyors of privatization step back and say “it’s out of our control, let’s get someone in here who can fix it back up.” Of course, Mercado and associates (one of the water board members is in business with US Filters, a Vivendi subsidiary), have set the stage for their corporate masters.

In Highland Park, which has its own water system, a slightly different scenario has played out. This small city, entirely surrounded by Detroit, was created early in the 20th century by Henry Ford to facilitate his first assembly line factory, long closed now.

The city was ordered into state receivership from budget deficits, but not allowed to claim bankruptcy. If the city had been allowed to file for bankruptcy, its population would have retained democratic control over their city. As it stands now, a state-appointed official and her hired assistants will decide what happens to Highland Park and its water system.

Highland Park’s population has dropped from 60,000 to about 16,000 residents. Of those remaining, most are either over 65 or under five years old. These remaining citizens pay the highest water rates in the country, bills range from $500 to $4,000 for a three-month period.

Citizens are not allowed to make payments, unless they can pay at least half of the outstanding bill up front. All bills are “estimated,” and must be paid even if they are contested or service is shut off. Unpaid water bills have been attached to property taxes and foreclosure threatened on several residents.

Highland Park is overwhelmingly African American, and racism has been a factor in determining the level of involvement and concern shown by the rest of the state. Two organizations, Michigan Welfare Rights Organization and Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, have drawn the public’s attention to the abandonment of “sacrifice communities” to the brutality of corporations.

In Highland Park, with water and sewerage rates so high, unemployment rates high and many residents on fixed incomes from retirement or disability, entire streets have been shut off from water. The public health implications of this are enormous, as are the social repercussions. Fatal fires have resulted from families lighting their water pipes on fire, believing them to be iced up (their heat having also been turned off). Fire fighters have been unable to put out fires in residences because water was unavailable.

Highland Park residents have confronted the three administrators in charge of their water system at a recent hearing and charged them with operating from a secret agenda. Ramona Pearson, the city manager was appointed by newly elected Democratic governor Jennifer Granholm.

Pearson in turn hired Jan Lazar, who then hired Steve Egan, her fellow vice-president in the pro-privatization consultant company Mercer Group. Lazar and Egan are listed on the web site, as well as the group’s agenda. Lazar’s specialty is the “restructuring” of benefits and pensions, which she decimated in many cities before coming to Highland Park.

A temporary restraining order is currently in place to curtail some of Lazar’s predations on the Highland Park city workers’ benefits and severance pay. Steve Egan, who works four hours two days a week in Highland Park for $90,000 and commutes from Georgia, contracted out a portion of the municipal system to a firm from Alpena, which now performs armed water shutoffs in Highland Park.

According to still unsigned, but pending international treaty obligations, this partial privatization of a public entity would open the door legally to a bid to privatize the entire system. It’s called leveling the playing field for corporations — and if you don’t do it they can sue for lost profits.

Water “Mining” and Ice Mountain

In the water war for profit, some companies have chosen the path of water extraction in a “get rich quick,” post-WTO scheme. According to world trade agreements, once an entity is sold as a commodity, it can no longer be protected by local legislation as a public resource or regulated for the public good.

Corporations are extracting water to bottle and sell back to consumers, to industrial farms, to mines (for use as a slurry to carry ores), to water-scarce nations in giant bags and tanker holds, etc. Many times, because this is a new market, the water is taken for free (having not had a previous “value” assigned to it) and, aside from mining costs, the sale of the water is pure profit for the corporation.

I will use Michigan’s Ice Mountain as a case study. Michigan holds 20% of the world’s fresh water. Much of that water lies below the surface, unmapped and unprotected by any law. This makes the region a prime (though not the only) target for privatization of groundwater.

In Michigan, Nestle found a location to build a water bottling plant. Actually, their research yielded 37 potential sites, but identified one that they felt was both profitable and substantial, but also demographically vulnerable. Nestle (Perrier Spring Waters of America, Ice Mountain) had tried to set up a water mine in Wisconsin, but the residents got wind of the plan early and organized to prevent it from happening.

Wary of community activists and under time pressures to locate another pump site (their site in Pennsylvania was drying up, and had some contamination problems), they searched for plentiful water beneath an unorganized community. The location they found for their Ice Mountain brand bottling plant is in Stanwood, MI.

A poor, small town, with high unemployment, an established Amish community, and made up of mostly retired family farmers, Stanwood was perfect for their purposes. Ice Mountain bought off three commissioners to get the one-time fee ($85) permit from a neighboring community and put out promises to Stanwood that 200 jobs would come with the plant.

As of this time, around 100 people work for the facility, most of them truck drivers who travel all over the United States. Several of the jobs were organic chemistry positions requiring doctoral degrees and experience in the bottling business — not a lot of unemployed organic chemists in Stanwood, so Nestle moved them from other facilities.

Even the construction phase of the project brought nothing to Stanwood. The construction of the monstrous two-mile long cement box facility was done by an out-state construction company. The roads were “improved” — paved at the county’s expense<197>so that around 100 trucks a day could pass in and out of the facility.

This giant plant with moveable/expandable walls replaced a woods and a small pond. The pump site is twelve miles away, the pipeline also built by non-union, out-of-state labor. It runs through wetland areas, the job being done so poorly that Ice Mountain was censured by the Department of Environmental Quality for siltation of the stream, but never fined.

With a cheap pumping permit, and a $10 million tax abatement package, Ice Mountain set up shop and began to pump 400 gallons of water a minute from an aquifer which is connected to Lake Michigan by the Little Mannistee River.

The aquifer is negligibly recharged, according to geologists. This means that over a 100-year cycle, only some of the surface water from the hydrologic cycle finds its way to the aquifer. When the water is gone, it’s basically gone for good.

This pumping is causing significant harm to the surrounding lakes and streams, destroying spawning habitat for pike and trout and nesting habitat for water birds. Furthermore, Ice Mountain destroyed nesting bald eagle habitat — where a pair of eagles had been for eight consecutive years — when it built roads into the forests to access their pump site.

One of the eagles flew over the first demonstration at the Ice Mountain bottling plant. It had come twelve miles to circle in ever widening loops over our heads until it appeared to disappear high above us.

The pumping is also causing a drop in water pressure to the local homes relying on well water. It is important to note a key fact about the local Amish, who rely on well water for their small-scale irrigation and organic farming. They are religiously prohibited from using any technology. If they lose their wells (which are not electrically pumped and rely on water pressure), they will be forced to move, ending one of the few non-technological cultures of the region.

When Nestle/Ice Mountain came in, they were not required to ask permission from local residents. They found corruptible decision-makers and set up shop quickly. They knew that if people found out, there would be a strong opposition to their location in Michigan, the heart of the Great Lakes.

By the time the word got out about what was happening, the woods were destroyed and the plant built. Local residents have held a non-binding referendum on the issue of Ice Mountain’s permit, and found that county-wide there was an overwhelming majority who opposed the plant (90%). In a classic case of corporate interests over democratic local control, the plant continues to operate, making over $1.8 million a day in profit.

India to Africa to Bolivia

The big water corporations — Suez, Vivendi (now Veolia) and RWE — have been able to use the World Bank and the IMF extensively to fund their operations in the “global south.” When Suez took over the water operation in Buenos Aires, all but $30 million of the $1 billion required for investment in new infrastructure was provided for by the World Bank.

Suez also used the World Bank to convince the Delhi Water Board to borrow money against future loans from the bank. When the promised money did not come through five years later, the Delhi Water Board was forced to sell some of its assets, part of its operations, to pay the first loan. Suez swooped in and bought the water treatment center at a cheap price.

The World Bank and IMF have both made water privatization a condition for the renewal of loans with countries of the “global south.” A random re<->view of IMF loans to forty countries during 2000 revealed that twelve countries had loan conditions that imposed water privatization or full-cost recovery (the language that Victor Mercado uses in the Detroit situation).

African countries, poor and debt-ridden, have born the brunt of most of these draconian measures. In South Africa, the World Bank refused to allow cross-subsidies of water from the central government to local authorities for the purpose of assisting poor communities. When water prices rose substantially in Johannesburg, in order to pay for the cost of dam projects elsewhere in Africa, people were faced with cutoffs for non-payment.

In Cochabomba, Bolivia, there was a general insurrection against the government and the multinational corporation, Bechtel, which had taken over managing the water department. (Readers may note the company’s other ventures, e.g. in Iraq.) Rates were raised in the suburban areas and Bechtel insisted that even rain water, gathered in cisterns in the poor communities not serviced by plumbing or no longer able to buy water trucked in by the company, belonged to Bechtel.

La Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y la Vida was formed to resist privatization. Demonstrations ensued that engulfed the entire city of Cochabomba in mass public upheaval and protest. Bechtel responded by cementing over the central well in the poorest neighborhood and raising rates.

After a School of the Americas-trained corporal shot and killed an unarmed 17-year-old demonstrator, the people rioted and burned down government and Bechtel corporate buildings. Eventually, the Bolivian government informed Bechtel that they could no longer protect the corporation’s interests and infrastructure from damage. Bechtel has responded by demanding $25 million in lost profits in a trade court. Bolivia is refusing to pay.

Currently, the water department is controlled by a diverse community/worker alliance that is striving to fix the problems Bechtel and the former unresponsive government department had caused.

Dirty Water Games

For all of their claims of expertise, the big water companies are best known for the speed at which munici<->pal water systems deteriorate under their expert care. In addition to murdering local residents, either directly through the use of force to guard their interests or indirectly through lack of access to the basic necessities of life, multinational water corporations are busily destroying the Earth for profit.

In the United States, the residents of Atlanta complained of their privatized tap water turning brown and smelling bad. In July of 1999, Northumbrian Water (a subsidiary of Suez) was declared by officials to have high levels of iron and manganese in their processed water and be unfit for drinking.

Vivendi, as well, produced through their subsidiaries in Tregeux, France, water unfit for consumption and filled with pesticide residues. In the United Kingdom, five water companies (Anglian, Severn Trent, Northumbrian, Wessex, and Yorkshire) were prosecuted successfully 128 times because of water pollution. One of those instances includes Thames Water’s actions in August 2001 to pollute with raw sewage a stream located within yards of a British community.

In addition to polluting the water, big companies were also guilty of wasting huge quantities of water from their refusal to maintain pipes, after taking control of the municipal systems. RWE’s new subsidiary, Thames Water, lost enough water through leaky pipes to fill 300 Olympic size pools every day for a year.

In the business of water mining, pollution has occurred when aquifers are pumped so low, that pressures change and, in the case of some Florida sites, sea water is pulled into the aquifer, turning it brackish. Nestle has contaminated at least one such site. In Pennsylvania, at another Nestle site, water bottled and shipped to distributors picked up a smell of “gasoline” — according to several consumers in the Chicago area. For several weeks, the Jewel store chain in Chicago took the Ice Mountain bottles off the shelf.

Fighting Back

All over the world, people are fighting against the “corporatization” of water and their lives. Protests range from public outreach and education efforts; local, and global network building; building alternative infrastructure; to outright insurrection to regain control over the community from corporations.

* In South Africa, the Anti-Privatization Forum is waging a campaign against water cutoffs in the town<->ships. In Soweto and Johannesburg, they are turning off water service of politicians who have facilitated the takeover by the big water companies.

Defense Teams are turning the water back on for victims of the shutoffs, and responding to calls for assistance. Thousands have taken to the streets in protest and have threatened to throw the African National Congress out in this next election, if they cave in to the World Bank’s demands and don’t guarantee basic essential services to all. Despite the obvious political assassination of at least one woman activist, resistance is strong and continues.

* In Plachimada, India, indigenous women have formed a camp to protect the water for their village from the water mining proposed by Coca Cola Company. In Delhi, where five workers have been killed on the job in a water treatment plant (because Suez did not want to buy routine safety and monitoring equipment), citizens are pursuing a criminal investigation and charging murder and negligence by the company.

Community groups are gearing up all over India for the January, 2004 World Social Forum, where tens of thousands, perhaps even hundreds of thousands are expected to come to Mumbai and demand transformative social change<197>including the de-privatization of the water.

* In Bolivia, where the people threw Bechtel out by force, La Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y la Vida are building their own community based public water system. Repudiating the false debt that Bechtel has placed upon them in court has freed up resources to create a water infrastructure that better serves the people.

* In Brazil, the Brazilian Workers Party has also built community-based public water systems, as in Porto Alegre, and demonstrated against privatization and corporate control with mass resistance.

* In France, community and environmental groups, like Eau Secours, have fought to take back community control over water services in the city of Grenoble.

* In Canada, opposition to the corporate takeover of water services in Toronto, Halifax and Vancouver has been a combined effort of communities and NGOs such as the Council of Canadians.

* In Ghana, the Philippines, Nicaragua and in Indonesia communities and water workers are facing off with water corporations and their own governments who are in collusion with privatization.

* In the United States, communities are fighting water privatization schemes from coast to coast, in cities like Detroit, Highland Park, Atlanta, Minneapolis, Tampa, Santa Rosa, Stockton, New Orleans, Milwaukee and Stanwood, among many others. Groups range from the Sierra Club and Public Citizen, to the New Black Panther Party and Earth First!

The water war is not going away on its own any time soon. The possible profits from the control of water are staggering. The top two water companies in the world together grossed over $88 billion in 2001 (according to Polaris Institute). This kind of money inspires capitalists to crimes against humanity and nature.

The only effective tactic has been popular resistance and revolt. In the words of Herman Hesse:

“We kill when we close our eyes to poverty, affliction or infamy.

“We kill when, because it is easier, we countenance, or pretend to approve of atrophied social, political, educational, and religious institutions, instead of resolutely combating them.”

ATC 108, January-February 2004