Against the Current, No. 85, March/April 2000

-

Women and Global Capitalism

— The Editors -

Elections in the Southern Cone

— Francisco T. Sobrino -

The Second Chechnya War

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

From Yeltsin to Putin: Modern Democrat Gives Way to Modern Nationalist

— Hillel Ticktin and Susan Weissman -

A Travesty of Justice: Why Peltier Remains in Prison

— Jack Breseé -

Behind the Confederate Flag Controversy: The Unfinished Civil War

— Malik Miah -

Grassroots Power, Women and Transformation: An Interview with George Friday

— Stephanie Luce -

Privatization by Stealth: Canadian Health Care in Crisis

— Milton Fisk -

The Rebel Girl: The State of Gay Marriage

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: New and Old Millenia

— R.F. Kampfer - Reflecting on the Battle of Seattle

-

The WTO's Nude World Order

— Bill Resnick -

The Clouds Clear: Labor, Seattle and Beyond

— Frank Borgers - Honoring International Women's Day

-

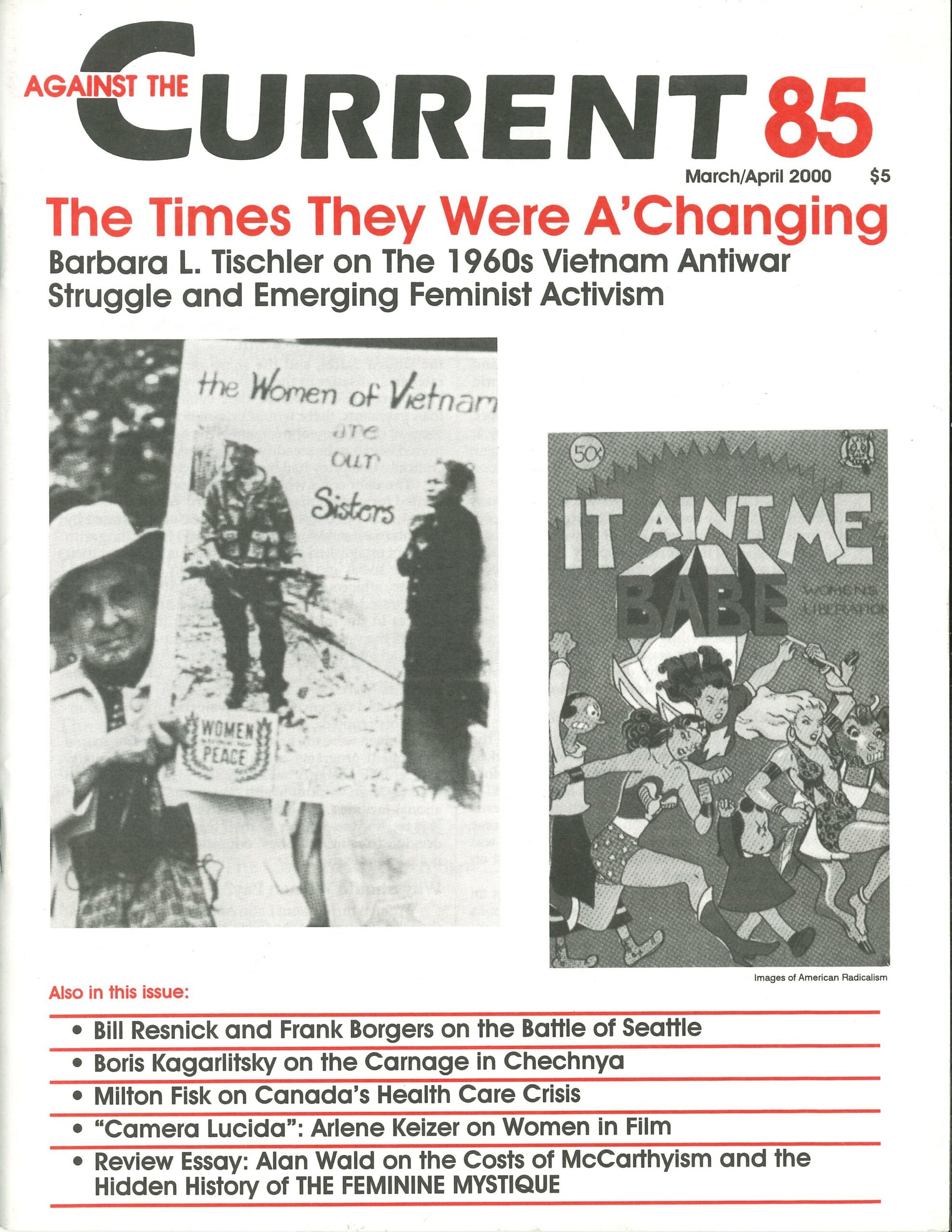

Antiwar Activism and Emerging Feminism in the Late 1960s: The Times They Were A'Changing

— Barbara L. Tischler -

Camera Lucida: Women on Film at Century's End

— Arlene Keizer - Reviews

-

The Costs of McCarthyism

— Alan Wald - More Reviews

-

A Classic Novel Revived: The Big Boxcar by Alfred Maund

— Jessica Kimball Printz -

Political Persecution in Puerto Rico: Uncovering Secret Files

— César Ayala -

Lessons of Life and Death from Henry Spira: By Any Compromise Necessary?

— Kim Hunter - Letters to Against the Current

-

`Natural Laws' of Economy

— Eric Hammel

Jessica Kimball Printz

The Big Boxcar by Alfred Maund. First publication 1957. Reprint, with a new introduction by Alan Wald. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999. 178 pages. $14.95 paperback

GIVEN THE LITTLE attention that the subject has garnered to date, we might well assume that the American radical novel was a casualty of the Cold War.

In its heyday of the 1930s, the radical novel attracted the attention of such literary lights as John Dos Passos and Sherwood Anderson, and inspired a legion of lesser admirers and would-be practitioners in “grassroots” style literary-political organizations, the John Reed Clubs, which sprang up from New York to California.

In the decades following World War II, however, the same deep-set national anxieties that fueled the meteoric rise of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his red-baiting minions apparently had a chilling effect on the genre and the allegiances of the many “Communist sympathizers” who formerly supported it.

Deserted in droves by authors seeking less politically painful avenues of creative expression, the radical novel plunged headlong into a moribund freeze that was only fitfully and temporarily thawed by a handful of its staunchest adherents.

Or so it would seem. The welcome reissue of Alfred Maund’s magnificent first novel should at once unearth and finally lay to rest our tacit, bleak assumptions about the Cold-War radical novel.

Undercurrents in the Cold War

The Big Boxcar is the ninth title, and the third Cold-War era title, in “The Radical Novel Reconsidered,” an ongoing series of reissues of left-wing fiction by U.S. writers undertaken by University of Illinois Press.

Together with its fellow Cold-War reissues, Alexander Saxton’s The Great Midland (1948) and Phillip Bonosky’s Burning Valley (1953), The Big Boxcar suggests a new paradigm for understanding the literary output of radicals during the Cold War: The wide range of radical activities they pursued may be seen as a vast network of underground rivers, inextricably connected to the surface and teeming with life, periodically bursting forth in wellsprings of enormous intensity and purity—in novels that are themselves the distillation of all that is best and brightest about the radical novel, and, indeed, about the novel in general.

In Maund’s case, the swift current of activism (which is meticulously detailed in series editor Alan Wald’s introduction to the reissue) ultimately generated three novels: The Big Boxcar (1957), The International (1961), and The Worthy Termites (1961).

The origins of this swift current lay in the horror evoked by the racism and social injustice that Maund, a Louisiana native (b.1923), witnessed every day as a resident of the deep South. The current deepened and gained momentum as Maund pursued a career as political journalist and editor.

Displaying a particular talent and penchant for writing on labor issues and race relations in the South, Maund contributed not only to local Southern newspapers but to radical journals such as Monthly Review, The Nation and American Socialist.

He also became affiliated with a variety of pro-integration and pro-union organizations, including the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF) and the International Chemical Workers Union, and openly supported social resistance movements, most notably the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott that made Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. household names.

Voice of the Oppressed

Given the particular tributaries of Maund’s activism, few would be surprised that it found fruition in a novel that, according to the author himself, was written to articulate “the social perspective of the Black downtrodden” and “make vivid the souls, so to speak, of the Black voiceless.” (xvii)

Yet even in its broadest outlines, such a project seems an almost unthinkably audacious one for a white man living and working (and hoping to continue doing both) in the heart of Alabama during the very years that saw racial tensions reach boiling points across the South amid the dismantlement of segregation laws and customs.

To embark on such a project would be equally unthinkable today, albeit for entirely different reasons, reasons that reflect how far our racial sensibilities have come over the last four decades. What was once a novel, courageous and incredibly enlightened approach for a white Southerner to take—claiming to speak for a Black underclass—would be deemed an act of rude presumption today.

But to judge The Big Boxcar according to the audacity (past or present) of its avowed aims, to relegate it to the realm of historical curiosity, would be to mistake its very essence and, in the process, deprive ourselves of the sheer pleasure of a “good read.” Through supple and subtly poignant prose, The Big Boxcar transcends the politics of its historical moment and sings with a freshness and clarity that are a true testament to Maund’s consummate skill as a storyteller.

The basic structure of the novel takes its cue from that of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales: Travelers, brought together by happenstance and a common goal, tell stories to pass the time.

What Maund’s characters share, however, may more properly be termed a plight rather than a pilgrimage, and as they tell their tales, their fates become entangled in ways that Chaucer never envisioned for his pilgrims.

Riding on the Run

Six African Americans, each on the run from a troubled past in a Jim Crow South, find themselves stowaways in the same boxcar of a northbound train.

Thrust into an awkward, desperate dependence on strangers by the exigencies of their situation (where one person’s false move could mean the discovery and capture of them all), the stowaways are initially keenly attuned to the weaknesses of others and wary of exposing anything about themselves.

The thirst and hunger, fears and boredom that they have in common, however, encourage them to interact, even as the close quarters of the boxcar and the impending peril of the next train stop compel them to establish among themselves a social order and a plan of action.

As the train nears Birmingham, they are joined by another fugitive whose identity and presence makes the capture of them all an almost foregone conclusion. I say “almost,” for the final fates of these characters, like the many elegant, suspenseful twists and revelations contained in the stories they tell, are matters best left for readers to appreciate firsthand.

With this in mind, I would advise readers to enjoy the novel itself before perusing the introductory essay. Still, one compound, common thread in this novel and its stories-within-a-story perhaps may be touched upon without prejudice to future readers: the idea of crossing, and the possibility of hope it affords.

In riding the rails, Maund’s characters not only cross the more mundane boundaries of state and county lines in hopes of clearing the Mason-Dixon line; they also move beyond the isolation of their own “private trouble” (2) into the solidarity of collective thought and action.

This transition is made possible in part by the characters telling stories, in their own words, that are themselves replete with momentous crossings.

Boundaries Defied

In Good-Rocking Poppa’s story, a chanteuse’s affair with a white doctor costs her dearly, not because of its interraciality in and of itself, but because she dares to find intellectual conversation, companionship, and “love” with such a man “for the man himself” (16), without regard to color. In so doing, she flouts many of the expectations of and divisions within both the Black and white communities.

Shorty relates a tale about a mysterious talking dog whose cross-species communion galvanizes a group of impoverished turpentiners to “trifle with the favor” (23) of the local sheriff.

In Teacher-Man’s story, members of the Gilead Assembly, who “had been waiting all their lives for somebody to give them a touch of hope and glory” (39-40), must consider whether a most unlikely duo is an answer to their prayers: an erstwhile no-account laundry delivery boy from their own congregation and the local white lunatic who engages him with a plan for an integrationist parade of sinners.

The Woman’s story recounts how an early interracial friendship, embarked upon with the innocent bravado of youth, dramatically changes the course of a woman’s life. After weathering enormous shifts in her status, class and occupation, the woman finds friendship in an interracial triad that inspires her courage in ways that put her very life, and the lives of her family, on the line.

In The Spook’s story, a janitor’s reefer-induced confidence threatens to propel him into a job as the newspaper’s first Black columnist, if he can survive cross-examination by a managing editor with identity issues of his own.

The final interpolated tale concerns one Sam Cutler, a field hand who spends the first three decades of life taking comfort in being “nothing, with nothing to be proud of and nothing to be shamed of.” (140)

The shattering of the safe and narrow circumference of Sam’s self begins when a county official forces Sam to become the janitor of the local schoolhouse. Whetted by furtive forays into the children’s lesson-books, Sam’s hunger for knowledge leads him into increasingly drastic avenues of research, avenues that pose more questions than they solve.

The Pain and the Hope

The crossings that permeate these stories almost always involve loss as well as gain; fear as well as courage; despair and disappointment as well as humor and happiness. And while hope in these stories may often be shown to be misplaced, or offer only a temporary stay to oppressive social forces at work, or fail to have the anticipated results, ultimately the idea of hope—its power to inspire men and women of all races to unite and dare to cross those lines—emerges unscathed.

Hope abides, survives against all odds, and becomes the tie that binds characters, and the novel itself, together. What results is a novel that is neither rosy nor nihilistic, but intensely real. May The Big Boxcar, like the train celebrated in the Negro spiritual, be “Bound for Glory” on its return trip.

ATC 85, March-April 2000