Against the Current, No. 80, May/June 1999

-

NATO's Road to War and Ruin

— The Editors -

Waiting to Inhale: Culture Wars or Unfinished Gratification?

— David Roediger -

The Fight for Leonard Peltier

— Hayden Perry -

CPE: Demystifying Economics--Interview with Elissa Braunstein

— Stephanie Luce -

Race and Politics: Indonesia's Ethnic Conflicts

— Malik Miah -

A Profile of East Timor's Jose Ramos-Horta

— Conan Elphicke -

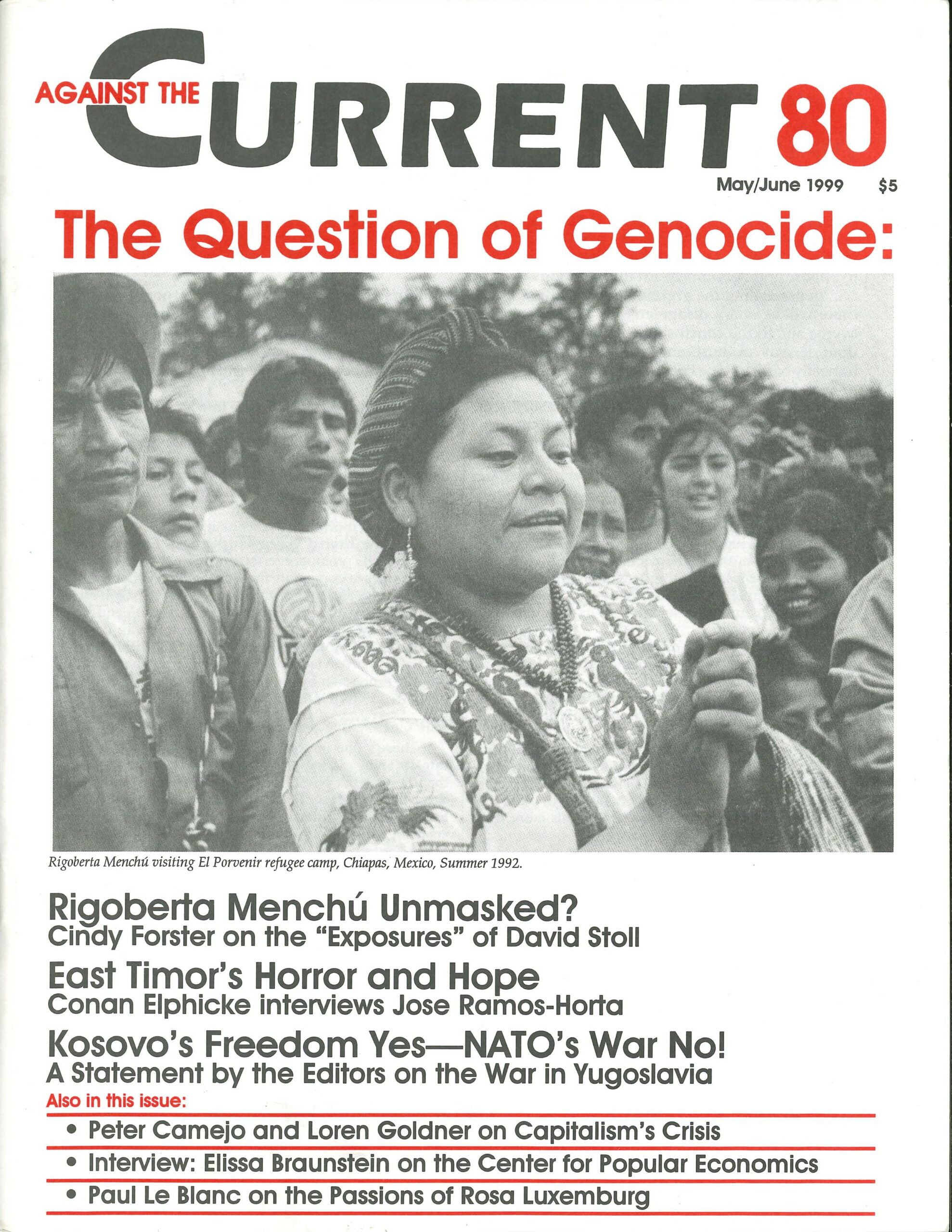

Rigoberta Menchú: A Witness Discredited?

— Cindy Forster -

A Revolutionary Woman in Mind and Spirit: The Passions of Rosa Luxemburg

— Paul Le Blanc -

Random Shots: Weird Sex and Boiled Bacon

— R.F. Kampfer -

The Rebel Girl: A Question of Rape

— Catherine Sameh - Capital's Global Turbulence: A Symposium

-

"Total Capital" Rigor and International Liquidity: A Reply to Robert Brenner

— Loren Goldner -

The Great Bull Market vs. Looming Crisis: On Brenner's Theory of Crisis

— Peter Camejo - Dialogue on Workers in a Lean World

-

On Workers in A Lean World

— Kim Moody -

A Rejoinder

— Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval - Reviews

-

Glaberman and Faber's Working for Wages

— Sheila Cohen -

The Availability of Utopian Thought

— Terry Murphy - Letters to Against the Current

-

Letter and Response on Mumia Abu-Jamal

— Sidney Gendin and Steve Bloom - In Memoriam

-

Comrade and Friend: Bob Strowiss 1919-1999

— Edmund Kovacs

Hayden Perry

LEONARD PELTIER, A Native American class-war prisoner, has served twenty-three years in federal prisons for a crime he did not commit—and authorities admit they do not know who did it.

Now Peltier is enduring unremitting agony from a medical condition. He suffers from maxilla-facial, a rare disease that locks his jaws so he cannot open his mouth enough to eat solid food. He suffers constant excruciating pain.

Prison medical procedures have worsened his condition. While doctors at the Mayo Clinic have offered to treat Peltier, prison authorities refuse permission.

Peltier, a Ojibwa-Lakota, is serving two consecutive life sentences because he came to the aid of brother Indians in June 1975 on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

Multinational corporations were trying to get mining rights on reservation land. This lead to serious dissension in the Lakota Tribe. Tribal Chief Dick Wilson supported the mining interests, and recruited a band of followers, known as GOONS, to physically intimidate the opposition.

Beatings and shootings kept the reservation in a state of siege. In the face of this reign of terror, defenders of tribal rights called on the American Indian Movement (AIM) for help. AIM had been founded to build and strengthen the First Nations in the struggle for survival and self-determination.

Between 1973-75 there was a massive buildup of FBI personnel in South Dakota. During that period there were sixty violent deaths and countless injuries to AIM members.

On June 26, 1975 there were 150 armed FBI agents, Bureau of Indian Affairs Police, U.S. Marshals and local police roaming the Pine Ridge reservation. Two unmarked cars rushed into the AIM camp. AIM members assumed they were under attack from GOON thugs and defended themselves. In the course of the firefight one AIM activist and two FBI agents fell dead.

Federal prosecutors say they do not know who shot the agents, but later arrested two men, Dino Butler and Bob Robideau. They looked for Leonard Peltier but he fled to Canada, knowing he would have little chance of a fair trial.

U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger leaned on the Canadians to turn over Peltier. The FBI produced a witness who said she saw Peltier shoot the FBI men. Later she recanted, and confessed she had never seen him anywhere at any time. But on the strength of this perjured testimony the Canadian government denied Peltier the right of political asylum and turned him over to vengeful U.S. agents.

Butler and Robideau were tried in Cedar Rapids, Iowa for shooting the FBI agents. They were acquitted on grounds that they had acted in self-defense. Didn’t this verdict exonerate all those who were being fired on and firing back on that fatal day?

The government did not want a repeat of the acquittal on grounds of self-defense that freed Butler and Robideau. They moved Peltier’s trial to Fargo, North Dakota, believed to be a more conservative venue with little sympathy for Indians. Federal authorities also found a judge who had dealt harshly with Indian defendants in the past. (The government made no effort to find who killed the AIM activist during the June 26 shootout.)

At Peltier’s trial the government demanded that he be convicted of two murders. Presenting witnesses who later recanted, governmental authorities framed Peltier. FBI documents received through the Freedom of Information Act also reveal implementation of a plan to convince the trial judge that his personal safety and the security of his courthouse were in danger from Peltier’s family and friends. This was the atmosphere in which the trial was conducted.

Later the government admitted it did not know who fired the fatal shots. They then claimed that they charged Peltier only with “aiding and abetting” in the shooting. But conviction of “aiding and abetting” would not have permitted the savage sentence imposed: two life sentences to be served consecutively.

Although government misconduct was admitted, three appeals to appellate courts have been denied. The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals declared that Peltier’s trial and previous appeals had been riddled with FBI misconduct and judicial impropriety including coercion of witnesses, perjury, fabrication of evidence and suppression of evidence that could have proved his innocence. Despite this, the court refused to order a new trial.

An application for parole submitted in 1993 was turned down after a five-minute consideration despite 20 million signatures of support. Peltier cannot apply for parole again until 2008.

The court of world public opinion has recognized Leonard Peltier as one of the longest held political prisoners. In twenty-five countries Committees of Support have been formed. Fifty-five members of Congress, 67 members of the Italian Parliament, U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye, Senator Paul Wellstone, and South African President Nelson Mandela are among the nearly 50 million people who demand freedom for Peltier.

The Demand for Clemency

Time is getting short. With Peltier’s health deteriorating, under shameful medical care, his life is in danger. The final recourse left is a request for a decree of executive clemency by President Clinton.

This plea was made three years ago. The executive has been sitting on the papers ever since. Every possible lever must be used to pressure the Clinton Administration to take action and grant clemency. (Write to President Clinton at the White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, DC 20500, phone 202-456-1414 or fax 202-456-2461; send copies to U.S. Pardon Attorney Roger C. Adams, 500 First Street NW, Suite 400, Washington DC 20530 or phone 202-616-6070. To demand that the federal government allow Peltier to be treated for his medical condition at the Mayo Clinic, write to Ms. Kathleen Hawk, Director, Bureau of Prisons, 320 First Street NW, Washington, DC 20534, fax 202-514-6878 or phone 202-307-3198.)

A Leonard Peltier Organizing Conference is scheduled for June 25-27 at Haskell Indian Nations University, Lawrence, Kansas. Its stated purpose is to build a stronger network to free Peltier and to develop concrete strategies to gain his release. The conference is open to anyone who cares about justice, and is moved by Peltier’s own words when he writes, “Despite the suffering I feel and the torturous years of imprisonment I have endured, deep down I have no regrets in fighting for my people—in fighting for what is right. . . .”

(For further information on the conference, contact the Leonard Peltier Defense Committee, P.O. Box 583, Lawrence, KS 66044, 785-842-5774, fax 785-842-5796, e-mail lpdc@idir.net)

ATC 80, May-June 1999