Against the Current, No. 78, January/February 1999

-

The Cynicism and the Slaughter

— The Editors -

The Labor Party's Pittsburgh Convention

— John Hinshaw -

The Labor Party in the Big Picture

— Jane Slaughter and Rodney Ward -

Hurricane Mitch and Disaster Relief: The Politics of Catastrophe

— Anne Schenk -

Remembering Pinochet's Coup: A Taste of Justice for Chile

— Marc Cooper -

El Salvador's New War: Lesbian/Gay Activism Confronts “Social Cleansing”

— Anne Schenk -

The CIA and the "Peace Process"

— Harry Clark interviews Professor Israel Shahak -

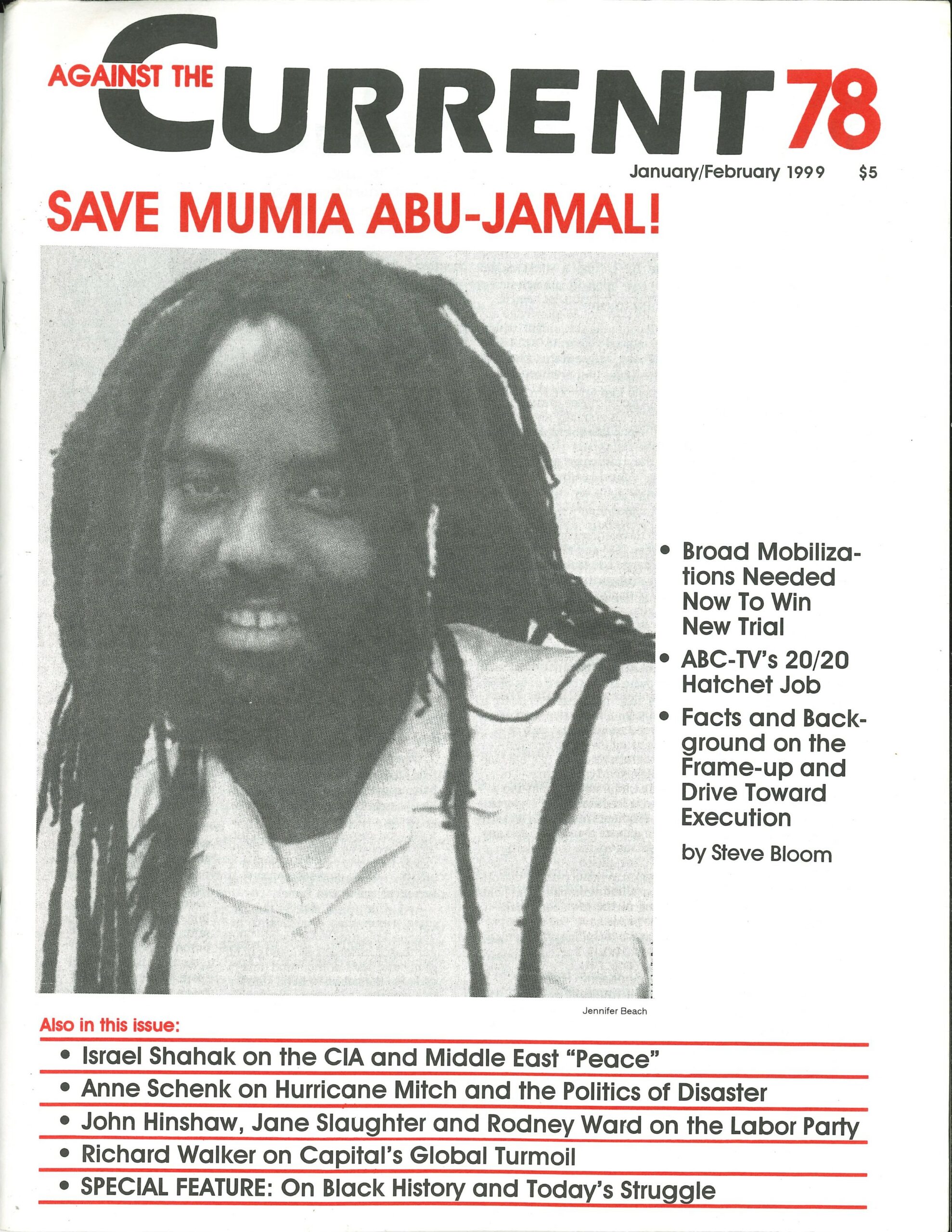

PA Supreme Court Rejects New Trial for Mumia

— Steve Bloom -

An Introduction: Capital's Global Turbulence

— Richard Walker -

Capital's Global Turbulence

— Richard Walker -

Random Shots: Notes From Starr's Chamber

— R.F. Kampfer -

The Rebel Girl: Barbara Kingsolver's Triumph

— Catherine Sameh -

Radical Rhythms: A Band Whose Time Has Come

— Daniel L. Widener - Black History and Today's Struggle

-

In Honor of Assata Shakur

— Daniel L. Widener -

Race and Politics

— Malik Miah -

Race from the 20th to the 21st Century: Multiculturalism or Emancipation?

— E. San Juan, Jr. -

Review: Moving Beyond Black and White?

— Tim Libretti - Reviews

-

Labor Organizing in a Lean World: Workers of the World Unite?

— Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval -

The Cocaine-Contra-CIA Complex

— Larry Gabriel -

Halting British Fascism

— Gerd-Rainer Horn -

An Experiment in Democracy

— Dan La Botz -

Surrealism Against Racism

— Michael Löwy -

Capital on CD-Rom, Cat Optional

— Joel R. Finkel - Dialogue

-

Black Liberation, Working-Class Unity, and the Popular Front: A Reply to Mel Rothenberg

— Michael Goldfield -

After Stalinism: An Exchange

— Dave Linn and Susan Weissman -

A Rejoinder: Strategy or Doctrine?

— Mel Rothenberg - In Memoriam

-

A Farewell and Tribute: Rose Lesnik, 1924-1998

— Estar Baur

Steve Bloom

THE OCTOBER 29 ruling by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, turning down Mumia Abu-Jamal’s appeal for a new trial, is one more proof that the U.S. criminal court system has very little interest in justice.

Justice demands, at the very least, a new trial in this case. The seven judges of Pennsylvania’s highest court, however, have clearly demonstrated that they are simply one more cog in a government machine of death which is determined to take Mumia’s life—not because he is guilty of any crime, but because he is Black and militantly opposed to the oppression of poor and working people, especially people of color.

The court’s opinion was unanimous. It was even joined, notably, by one Justice—Ronald Castille, who worked in the Philadelphia District Attorney’s office before he was elected to his present position. And while he was a prosecutor Castille signed the papers filed against Mumia’s original appeal.

Despite this clear conflict of interest Justice Castille refused to recuse himself (remove himself from the case) as demanded by Mumia’s attorneys. In making this request the defense team also noted that Castille, in his bid for election to the court in 1993, was endorsed by the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police (FOP)—an organization which has for years been on a campaign to promote Mumia’s execution.

Justice Castille responded: “At the outset, I note that the very same FOP which endorsed me during earlier electoral processes also endorsed Mr. Chief Justice John P. Flaherty, Mr. Justice Ralph Cappy, Mr. Justice Russell M. Nigro, and Madame Justice Sandra Schultz Newman. If the FOP’s endorsement constituted a basis for recusal, practically the entire court would be required to decline participation in this appeal.”

That remark would seem to tell the whole story. If Mumia Abu-Jamal is going to get any justice it is, clearly, going to have to be won in the streets. We cannot rely on the courts.

The Background

Mumia was convicted in 1982 for killing a Philadelphia police officer, Daniel Faulkner. The scenario that surrounded his trial is chillingly familiar to anyone who has studied the workings of the death penalty since it was reintroduced into the United States in 1976.

Mumia is Black. He was incompetently “defended” by a court-appointed attorney. The police intimidated witnesses, manufactured evidence that would incriminate Mumia, and suppressed evidence that would exonerate him. And the jury was manipulated to exclude Blacks. A recent study of ten years of the death penalty in Pennsylvania found that in capital cases Black jurors were five times more likely than whites to be excused. In Mumia’s trial, however, the figure was 16.5 times more likely.

In addition Mumia had one more strike against him as far as the courts and police were concerned. He is a former Black Panther and an award-winning journalist who consistently (and effectively) attempted to expose police abuse and corruption in Philadelphia.

The trial was assigned to hanging Judge Albert Sabo, who held the U.S. record for death sentences handed down. Sabo was once denounced by five assistant District Attorneys, who issued a statement explaining that it was impossible for any defendant to get a fair trial in Judge Sabo’s court.

Sabo also heard the initial phase of Mumia’s latest appeal, during which he upheld every motion made by the prosecution while denying every one made by the defense. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court, however, insisted that it could find no basis to conclude from this rather distinctive pattern (or from anything else that happened during the original trial or the appeal process) that there was any bias on the part of the judge.

Judges in Wonderland

Mumia’s case differs from that of most death-row inmates in one important respect: Over the years a substantial movement has developed to prevent his execution and to win a new trial.

His legal appeal has been taken on by a top team of attorneys headed by Leonard Weinglass. As a result of the work done in preparation for this appeal, the absurd miscarriage of justice that passed for a trial in 1982 is now well documented.

The facts are easily accessible to anyone who cares to delve into the matter—in print, through the internet, on video, etc.—and all of this sordid history was spelled out in the legal papers placed before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

A portion of this record is documented in the text of the New York Times ad reproduced in the box below. But there’s much more. For example, there were three government “eyewitnesses” who supported one or another aspect of the case against Mumia. But their testimony is suspect. Another witness, Veronica Jones, who was called by the defense at the trial, now says that she lied in court because the police had threatened her if she refused to do so. This should cast some doubt on the credibility of others who testified, but it is not the only reason to be skeptical.

In an unrelated recent case a woman by the name of Pamela Jenkins appeared as the star government witness in a trial against six police officers, from Philadelphia’s 39th District, who were convicted on charges of gross misconduct. In a statement signed for Mumia’s attorneys Jenkins explained that one of the convicted officers, Tom Ryan, had tried to compel her to give false testimony against Mumia in the original trial. She further said that during this same period Cynthia White—the only one to testify in court that she actually saw Mumia fire his gun at Officer Faulkner—had told her that “she [Cynthia] was afraid of the police and that the police were trying to get her to say something about the shooting.” Apparently they succeeded.

Despite all of this, the judges of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court found against Mumia’s appeal on every single point of fact and of law. They concluded—as Sabo did—that all of the testimony in the original trial remains credible, and that all the witnesses who have since come forward to say that they were coerced by the police are now not telling the truth.

The judges chose to accept at face value the tale of two officers who failed to say anything about Mumia’s alleged hospital-bed “confession,” and one of whom even wrote in his notebook that Mumia said nothing at all the night of his arrest, and then suddenly “remembered” this vital evidence two months later.

They disregarded the note in the medical examiner’s report (never introduced at the trial because the defense was never informed that it existed) which indicates the fatal bullet could not have come from Mumia’s gun. There is forensic evidence which proves that the bullet which wounded Mumia could not have been fired from the positions Faulkner and Mumia were in according to the state’s own account of events, and that Mumia could not have been as close to Faulkner as is alleged when he is supposed to have fired the first shot. None of this was brought out before the jury because the defense was provided no money by the court to hire a forensic expert of its own.

Indeed we find ourselves in a legal Wonderland: Verdict first, evidence later—as far as the honorable judges of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court are concerned. For anyone else there should, at the very least, be a question of reasonable doubt.

Federal Appeals

The next step on the legal front will be an appeal to the Federal courts. But this is now much more difficult for death-row prisoners.

In 1996, during the anti-terrrorist hysteria that followed the Oklahoma City bombing, Congress passed and President Clinton signed the “Effective Death Penalty Act.”

Prior to that law federal judges undertook an independent review of the facts of any death-penalty case which came before them. At the present time this is prohibited. According to the new law the federal courts must accept the facts of Mumia’s case—and any other death-penalty case—as those facts have been determined by the state courts.

So all of the Wonderland interpretations of Judge Sabo, now upheld by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, will, if this law is applied, be taken as established fact when the appeal comes before the federal courts. This puts an enormous—possibly even insurmountable—burden on the defense to justify federal intervention.

There is, in addition, a bizarre legal formulation in the new law which requires the federal courts to accept determinations of law by the state courts even if these interpretations violate the federal constitution—so long as they are not found to be “unreasonably wrong.” Almost any legal ruling can conceivably be accepted under such a formula, a fact which—according to the National Association of Defense Lawyers—”creates arbitrary and virtually insurmountable obstacles for prisoners.”

Of course, legal grounds for appeal remain—including the question of whether the “Effective Death Penalty Act” itself, with its restrictions on federal appeals, is constitutional. But the legal effort will certainly be an uphill struggle.

Broad-based Movement Needed

The unanimity of the verdict by the Pennsylvania court, even more than the fact of that verdict, should be taken as an indication that this case is going to be won or lost primarily on a political battlefield.

The ruling powers would seem to have made a clear decision that they want to drive ahead with Mumia’s execution no matter what the facts may be. And federal court intervention, as we have seen, cannot be relied upon.

For social activists this case should take on a status similar to that of some landmark historical struggles carried out to stop the executions of people like Joe Hill (Utah 1915), Sacco and Vanzetti (MA 1927), and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg (federal government, 1953).

It is somewhat chilling to remember that in each of these cases, despite massive world-wide campaigns of protest, the government went ahead and carried out its legal murder anyway.

Today the movement to save the life of Mumia Abu-Jamal is far weaker than in any of these previous situations. That should give us a sense of what we are up against. If we are going to save the life of Mumia Abu-Jamal then there is substantial work to be done.

Yet the facts of this case are so blatant, the case for reasonable doubt so clear, that it gives our side a definite advantage if we are capable of utilizing those facts effectively.

The task is to get out the truth to the broadest possible audience—far broader than the relatively small circles of committed radicals and revolutionaries who have so far been the most visible in rallying to Mumia’s defense. We have to reach out to unions, church groups, college and high-school students, and others in the “mainstream.”

Immediately after the Pennsylvania court’s decision emergency protests were held, turning out hundreds of activists in several major cities, and smaller numbers elsewhere.

On November 7 regional mobilizations took place—with 1,000 participants in Philadelphia and 2,500 in San Francisco, along with smaller actions in other places. So there is a good base of supporters already involved who can begin to do the needed work.

The forces coordinating the national defense effort have called for major conferences in January and February in several cities, including Philadelphia, New York, Chicago and San Francisco, plus mobilizations for Mumia’s birthday, April 24, in Philadelphia and San Francisco .

It will be important to take advantage of the opportunity these activities provide to substantially broaden the appeal of the movement. And if we are going to succeed in reaching out beyond the already-committed core of activists we need to acknowledge that much of the “revolutionary” rhetoric which many have brought to actions around Mumia constitutes a self-created obstacle, one which makes it harder to talk to that broader audience.

It is essential to now focus quite consciously on trying to convince every person with even a modest commitment to justice and human rights in this country, most of whom do not consider themselves revolutionaries, that they have a personal stake in whether Mumia lives or dies, and therefore in whether he gets a new trial.

This approach by the movement to save Mumia’s life would be, in the end, the most revolutionary—because it could create the biggest potential problem for the U.S. ruling class. If the State of Pennsylvania decides to drive ahead with this execution we will be in a position to expose the naked reality of class, and white supremacist, rule in the U.S.A. to hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, who now have illusions in a system which (they have so often been told) guarantees “justice for all.”

It is this potential, and only this potential for massive numbers to discover the real truth about racist justice in capitalist America, which has any chance of forcing the State of Pennsylvania to hesitate in its legal murder campaign. All of our organizing strategies should be planned accordingly.

Steve Bloom is a member of SOLIDARITY’S Prison Issues Working Group.

ATC 78, January-February 1999