Against the Current, No. 69, July/August 1997

-

The Republicrats' Phony Budget War

— The Editors -

The Los Angeles Bus Riders Union

— Scott Miller -

The Consumer Price Index "Reform"

— James Petras -

Britain's "New Labour"

— Harry Brighouse -

Woman-Centered, Activist Agendas

— Deborah L. Billings -

The Remaking of the Congo

— B. Skanthakumar -

The Roots of the Rebellion

— B. Skanthakumar -

Kabila's Friends

— B. Skanthakumar -

Mobutu's Loot and the Congo's Debt

— B. Skanthakumar -

Humanitarian Intervention

— B. Skanthakumar -

The AFDL and Its Program

— B. Skanthakumar -

Mining Congo's Wealth

— B. Skanthakumar -

Pornography, Violence and Women-Hating

— Ann E. Menasche interviews Diana Russell -

The Rebel Girl: Looking at the Gender Grid

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Fables of Bill and the Newt

— R.F. Kampfer - Exploitation and Upsurge

-

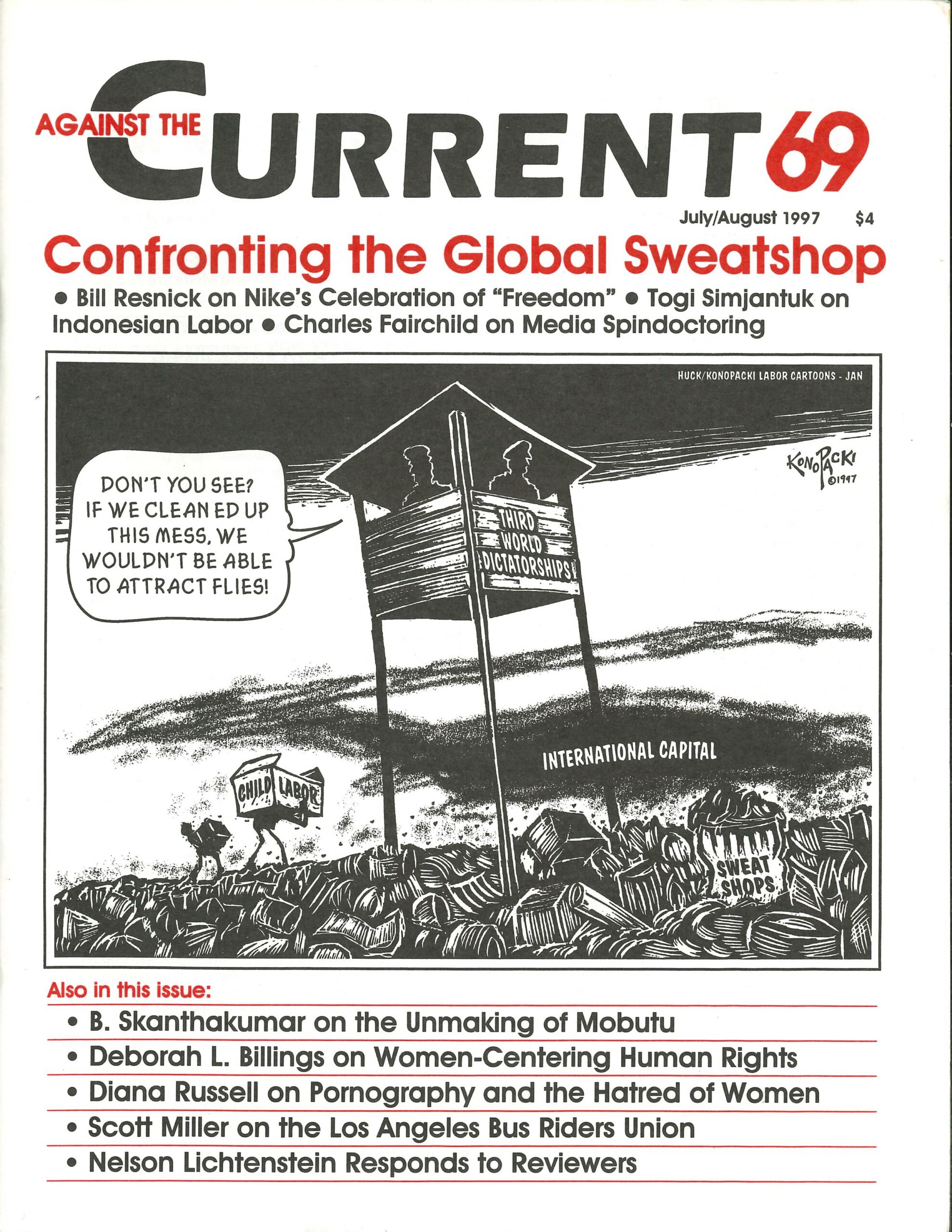

Global Sweatshops' Media Spin Doctors

— Charles Fairchild -

Socialism or Nike

— Bill Resnick -

Indonesia's New Social Upsurge

— Togi Simanjuntak -

Fellow Workers, Fight On!

— interview with Muchtar Pakpahan - Reviews

-

Asian American Incorporation or Insurgency?

— Tim Libretti - Dialogue

-

A Response to Reviewers

— Nelson Lichtenstein - In Memoriam

-

Albert Shanker, Image and Reality

— Marian Swerdlow and Kit Adam Wainer

Deborah L. Billings

“Women have the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The enjoyment of this right is vital to their life and well-being and their ability to participate in all areas of public and private life.” — Section C.89, Beijing Platform for Action

WOMEN’S SEXUAL AND reproductive health is intimately tied to their access to the full range of human rights guaranteed by both national law and international treaties and conventions. In recent years, recognition of this fundamental link has spurred dynamic organizing by women worldwide, particularly since the Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing in 1995. Renowned reproductive rights leaders, Rebecca Cook and Mahmoud Fathalla, assert that “. . . improvements in women’s health need more than better science and health care — they require state action to correct injustices to women.”(1) In this vein, activists have begun to utilize human rights tools, including international treaties and conventions, to significantly move debate and action toward changing the structural conditions which shape women’s sexual and reproductive health and, ultimately, their ability to fully participate in all realms of personal and public life.

Brief Historical Overview

Across time and cultural contexts, women’s sexuality has been highly regulated and scrutinized while, at the same time, subject to intense secrecy and silence. Beginning in the 1960s, these dynamics were intensified as Northern states pushed forward a “development” agenda focused almost exclusively on controlling the South’s “demographic explosion” as the way to address a wide array of issues including poverty, economic stagnation, violence, and environmental degradation. While often not explicitly named, women’s sexuality and, in particular, their reproductive capacity, were targeted for control. For example, in India coercive sterilization practices have been documented in which physicians, not women, decide when a woman should stop childbearing.

Poor women of the global South, as well as poor women and women of color living in Northern countries, have most acutely experienced attempts to control their fertility. Women’s own needs, desires, perspectives and concerns have been conspicuously absent from the population control approach, whose central focus is disembodied reproductive organs which need to “stop producing.”

During the 1970s, women’s health movements throughout Southern and Northern countries began to challenge and resist the rationale of population-based policies, continuously emphasizing their coercive dimension. Throughout the 1980s, feminist non-governmental organizations (NGOs), networks, and grassroots movements pushed forward the joint concepts of reproductive health and reproductive rights in an effort to shift both thinking and resources toward approaches which fully incorporate women’s participation in the development of programs and policies.

Such movements include The Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights, which doubled its membership of 800 in 1988 to 1,655 in 113 countries in 1992; The Latin American and Caribbean Women’s Health Network which incorporates over 2,000 women’s groups; and The International Women’s Health Coalition, which has contact with thousands of groups in Southern countries. Many groups have grown out of their involvement with anti-imperialist and democraticization struggles and thus draw explicit links between women’s health, political participation and empowerment, economic rights, and self-determination.

Global Conferences

These civil society movements played an important role in shaping the debates presented at a series of global conferences organized by the United Nations throughout the 1990s. They did so by drawing on legally binding human rights treaties, such as the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and demanding that their contents be integrated into meeting agendas. Three conferences in particular stand out as significant in women’s struggle for reproductive and sexual rights within the context of human rights:

* World Conference on Human Rights, Vienna, 1993: This global conference established that the human rights of women are an integral and inalienable component of universal human rights and that violations of women’s rights are deeply rooted in social, political, and economic inequities. The Vienna conference also recognized that health, including reproductive health, is central to development. Yet women’s health is constantly threatened by violence, discrimination, and women’s lack of access to services. As such, development requires that broad-based changes are made at multiple levels in societies.

* International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 1994: At this conference, 184 governments endorsed the Programme of Action, an international blueprint for achieving a balance between the needs of the world’s people and their use of its resources. It is the first international agreement on population in which women’s reproductive health and rights are central to the concept of development and in which human rights principles are applied to ensure that policies and resulting programs are truly voluntary and respectful of women. For example, paragraph 4.4c of the Programme of Action states, “Countries should act to empower women and should take steps to eliminate inequalities between men and women as soon as possible by . . . eliminating all practices that discriminate against women; assisting women to establish and realize their rights, including those that relate to reproductive and sexual health.”

* Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, 1995: The Beijing Platform for Action was the concrete result of this conference, a document which fully develops a rights framework for addressing women’s concerns and gives women tools to link such concerns — including sexual and reproductive health as enmeshed with other social issues — with global conventions to further fuel their work. Such a framework explicitly recognizes the value and importance of diversity and the multiplicity of experiences among women; it guides activists not to attempt to erase or ignore such differences but to use them to push discussion and action forward.

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

Both the ICPD Programme of Action and the Beijing Platform for Action define reproductive health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity in all matters related to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes.” Reproductive health, therefore, implies that “people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when, and how often to do so.” Reproductive rights, in turn, embrace “the basic rights of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children, and to have the information, education and means to do so; the right to attain the highest level of sexual and reproductive health; and the right to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence.”

At the same time, sexual health “aims at the enhancement of life and personal relations and should not consist merely of counselling and care related to reproduction and sexually transmitted diseases.” Sexual rights, as defined by the Platform for Action, include “the human right of women to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.”

Overall, both sexual and reproductive rights entail a woman’s rights to her bodily integrity and control, freedom from sexual violence, coercive medical practices including forced abortion, forced pregnancy and childbearing, and unsafe contraceptive methods. This also implies that health care providers must trust and take seriously women’s decisions regarding their bodies, a response which is currently all too rare. Examples abound, for example, in the Dominican Republic, Egypt, Indonesia, and Thailand, where women’s requests to have their Norplant contraceptive implants removed were denied despite their concerns about irregular bleeding, a sign for many women of ill-health.

Women’s Reproductive and Sexual Health in the World Today

Activists, policy makers, and health care providers who truly care about health within a rights framework face numerous challenges as they work to improve the overall health status of girls and women throughout the world. The summary paragraphs below outline some of the main reproductive and sexual health issues which need to be addressed from within a rights framework if women are to participate more fully in social life.

Pregnancy-Related Mortality and Morbidity: Around the world, 585,000 women die annually from pregnancy-related causes, most commonly hemorrhage, infection, unsafe abortion, hypertensive disorders, and obstructed labor. Approximately 15 million more women suffer from pregnancy-related injuries and infections which often go untreated and may be debilitating and lifelong. Ninety-nine percent of all pregnancy-related deaths occur in Southern countries, a full forty percent in African countries alone.

Unsafe Abortion: Unsafe abortion is defined by the World Health Organization as “a procedure for terminating unwanted pregnancy either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment lacking minimal medical standards or both.” In most countries throughout the world, legislation regulating induced abortion is either very or rather strict, allowing it only under narrowly defined circumstances such as rape, incest, or a threat to the woman’s physical or mental health. Over 20 million women undergo unsafe abortions each year, and the WHO estimates that 75,000 to 80,000 of these women die as a result. Millions more suffer from complications often leading to permanent conditions including infertility and chronic pain. Notably, the incidence of death and severe morbidity is highest in those countries where abortion legislation is most restrictive.

Women’s risk of death from unsafe abortion varies greatly between North and South, highlighting the differential access that women have to safe, legal abortion services and adequate health care services in case of complications. In Africa, one in every 150 women who experience an unsafe abortion risks dying while only 1 in 3,700 women in Northern countries runs this risk. An estimated 50 million other women in Southern countries suffer short and long-term complications related to unsafe abortion, including infection, infertility, and chronic pain.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs), Reproductive Tract Infections (RTIs), and HIV/AIDS: AIDS is now one of the leading causes of death for women of reproductive age throughout the world as heterosexual transmission is the fastest growing mechanism of infection. In 1994 alone, 500,000 women died from AIDS. By the year 2000 an estimated 13 million women will be infected with HIV, for the first time equaling the number of men projected to be infected.

Recent studies based in Africa, Latin America, and Asia report that RTIs — including STDs, and infection due to poorly performed gynecological services, childbirth, and abortion — are major causes of infertility in women. Sexual practices which focus on male satisfaction can also contribute to the transmission of STDs and HIV in already high prevalence areas of the world. One striking example is the practice of `dry sex’ in areas of southern Africa where women apply drying agents to their vagina in order to enhance their male partner’s sensation.(2) During sexual intercourse, lesions are likely to open thereby facilitating transmission.

Overall, STDs are much more easily transmitted from men to women and the consequences are more severe and long-term, including chronic pain, infertility, cervical cancer, and ectopic pregnancy. Symptoms are also less noticeable in women than in men resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. STDs, RTIs, and HIV can profoundly affect the lives of children whom women bear and care for. Han’a’s story illustrates this point:

“Han’a, a 16-year-old Egyptian woman, has been married for two years and has one daughter who is slow to develop physically and mentally. Han’a tested positive for syphilis and was treated but then reinfected when her husband came home from work in Libya. Han’a knew nothing about STDs, did not realize that her husband could infect her, and also never imagined that her daughter’s poor health could be connected to her own.

Fertility and Access to Contraceptives: At least 350 million couples in the world do not have access to modern contraceptives necessary to prevent and delay an unwanted pregnancy. At the same time, women in Southern countries have often been used as the `testing grounds’ for emerging contraceptive technologies. The use of Puerto Rican women to test oral contraceptives is a well documented case in point. To counter this in Peru, for example, feminist organizations have worked with national and international researchers as well as health care providers during the introduction of Norplant and Cyclofem to ensure that women are fully informed of their choices and their rights as research subjects.

Gender-based Violence: One-fifth to one-half of all women have been beaten by a male partner and studies reveal that 40 to 58 percent of all sexual assaults are perpetrated against girls aged 15 and under. Women who face sexual violence also face a higher risk of contracting STDs and RTIs. These women are, in turn, often beaten or abandoned by their partners and ostracized from their communities. In general, violence against women is a direct obstacle to women’s participation in community and extra-community life.

Forced prostitution/sexual slavery, prevalent where “market” systems develop in areas of extreme poverty and/or political and economic upheaval such as Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe, must also be included within this category of gender-based violence. Rape, as well as other forms of violence experienced by women during times of war, have only recently been more publicly aired as some of the most insidious forms of systematized violence against women.

Female Genital Mutilation-FGM: FGM, or female circumcision as it is more commonly known, is in many cultures a practice used to denote the purity and cleanliness of a woman as she passes from adolescence to adulthood. It is deeply entrenched within the cultural belief systems and practices of numerous societies, thereby making its eradication all the more difficult. Over 100 million women in the world today have undergone FGM in its multiple forms, ranging from removal of the clitoral hood to full infibulation (amputation of the clitoris and labia and stitching of the wound to leave a small hole for passage of urine and menstrual blood). An additional 2 million young women undergo the act every year. FGM frequently results in violent pain, shock, infection, hemorrhage, pregnancy loss, complications during childbirth and death.

Organizations, such as the Inter-African Committee on Harmful Traditional Practices, based in Ethiopia with chapters throughout the continent, and RAINBO (Research, Action, Information Network for Bodily Integrity of Women), based in New York are working to educate the public worldwide about the physical and mental health effects of FGM. This includes working with men, women, and adolescents in communities where FGM is practiced. They are also active in developing strategies to replace FGM as an acceptable rite of passage and sign of purity with other practices which signify a woman’s transition to adulthood and which ultimately are more empowering to women.

Cancer: The cancers women suffer are primarily those of the reproductive organs. In Southern countries an estimated 183,000 women die each year from cervical cancer, often directly related to infection from an STD.

While this list of issues may make addressing reproductive health seem a daunting task, women’s organizations have taken this challenge head-on. Numerous locally-based NGOs offer a variety of health and counseling services based on local needs. Internationally-based organizations, such as Marie Stopes International (MSI), also provide services within the local context. MSI is a clinic-based organization offering comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care to women in several countries throughout the world. In Sierra Leone where maternal mortality ratios are among Africa’s highest (2,500 per 100,000 births), MSI has offered a variety of services since 1988 including Pap smears, diagnosis and treatment of STDs, prenatal care, contraceptives, menstrual regulation services for unwanted pregnancies, and counseling services for menopausal women. By 1991 MSI clinics throughout Sierra Leone were seeing 4,000 clients per month, mostly low-income women traders in their mid- to late-twenties. MSI provides similar services to women throughout Southern countries where clinics are present.

Women, Empowerment, and Human Rights

Within patriarchal socio-economic systems throughout the world, women have had little to no direct say in decisions regarding marriage, education, and child-bearing, all of which are inextricably tied to their reproductive and sexual health.

Martha Ndlovu, a community health worker in South Africa, illustrates this as she speaks of her sister’s experience:

“In the early 1970s, my father forced my elder sister to get married. My sister was fourteen at the time, and she disagreed with him because she felt she was too young. But my father kept insisting and threatened to throw my sister out of the house if she disobeyed him. He went to a man who paid R200 as lobola [bride price] and then let this man come and collect my sister. My father just frittered that money away.”

“My sister was very unhappy in her marriage, but there was nothing she could do about the situation. She did not love the man, and he kept beating her because they could not live together. My sister became lean and ill. She had a heart attack and had to take constant medication. She has not been allowed to go to school, and she has to look after four children. Generally, married women are not allowed to make any decisions or say anything which contradicts their husbands. They cannot use contraception of any kind because they should ‘give birth until the babies are finished inside the stomach.’ It does not matter whether you give birth ten or fourteen times.”

While generally having less influence than their male partners in decisions regarding their own reproductive and sexual health, women have had an even smaller voice in the creation of programs and policies which directly affect them. To change this approach, feminist activists who focus on reproductive health and rights insist on reframing the usual question of, “Does program X improve women’s health?” to, “What is the nature and extent of women’s health problems and what, according to women in their varying life contexts, will be the best ways to address these problems?” This approach entails viewing health as a personal, political, and social experience rather than an exclusively epidemiological phenomenon or a matter of population reduction. Understanding women’s needs and preferences in this way must begin with women themselves.

From the preceding discussion of women’s contemporary health status worldwide, it is clear that, in general, women experience neither the reproductive or sexual health they have a right to enjoy. Given this, it is imperative that struggles for improving women’s health be placed within the framework of human rights, an approach which focuses on empowerment and legitimization. A human rights perspective turns women from objects into subjects of action and policy and legitimizes their concerns and needs as central to programs and policies which they help to develop.

States are also key actors in improving women’s health since, ultimately, they are responsible for guaranteeing the exercise of human rights and for preventing their violation. When we frame sexual and reproductive rights, as well as other health rights, as human rights we are then able to tap into international mechanisms for scrutinizing and assessing states’ actions toward the fulfillment of these rights. Activists now have at hand a wide array of tools from which to draw in their work to demand that states enforce and implement agreements which they signed.

Raising and politicitizing our demands for human rights, including the sexual and reproductive rights of women internationally, will contribute significantly toward improving women’s health and respecting women’s rights as human rights. These are basic steps called for in recent global conferences, including the 1995 Beijing Conference on Women. Ultimately, respect for and active compliance with human rights are necessary if women are to be active and equal participants in the construction of present and future societies.

Notes

- Cook, Rebecca J. and Mahmoud F. Fathalla. 1996. “Advancing Reprouctive Rights Beyond Cairo and Beijing.” International Family Planning Perspectives, 22(3): 115-121. This conclusion was emphasized in the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics’ 1994 World Report on Women’s Health.

back to text - Ray, Sunanda, Nyasha Gumbo, Michael Mbizvo. 1996. Local Voices, What Some Harare Men Say about Preparation for Sex. Reproductive Health Matters, Number 7.

back to text

ATC 69, July-August 1997